RESEARCH ARTICLE

A d factor? Understanding trait distractibility

and its relationships with ADHD

symptomatology and hyperfocus

Han Zhang

ID

1

*, Akira Miyake

2

, Jahla Osborne

ID

1

, Priti Shah

1

, John Jonides

1

1 Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States of America,

2 Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, United States

of America

Abstract

People differ substantially in their vulnerability to distraction. Yet, many types of distractions

exist, from external stimulation to internal thoughts. How should we characterize individual

differences in their distractibility? Two samples of adult participants (total N = 1220) com-

pleted a large battery of questionnaires assessing different facets of real-world distractibility.

Latent modeling revealed that these measures could be explained by three correlated-yet-

distinct factors: external distraction, unwanted intrusive thoughts, and mind-wandering.

Importantly, about 80% of the total variance in these three factors could be explained by a

single higher-order factor (d) that could be construed in terms of a person’s general distracti-

bility, and this general distractibility model was replicated across the two samples. We then

applied the general distractibility model to understand the nature of ADHD symptomatology

and hyperfocus (an intense state of long-lasting and highly focused attention). d was sub-

stantially associated with self-reported ADHD symptoms. Interestingly, d was also positively

associated with hyperfocus, suggesting that hyperfocus may, to some degree, reflect atten-

tion problems. These results also show marked consistencies across the two samples.

Overall, the study provides an important step toward a comprehensive understanding of

individual differences in distractibility and related constructs.

Introduction

Distraction is prevalent in our daily lives. As you read this article, you might be distracted by

the voices of people around you, by worries about an impending decision on a grant applica-

tion, or by fantasies about your next holiday travel plan.

Distraction has been a central topic in the study of cognition for well over 100 years [1]. In

this literature, one central theme has been that people differ substantially in how easily they get

distracted. Numerous studies have shown that people who report being distracted more easily

are at a higher risk of poor performance in school and work settings [2, 3] and even sometimes

prone to serious accidents [4]. The issue of interindividual variability also cuts across multiple

forms of psychopathology, most notably as a symptom of attention-deficit/hyperactivity

PLOS ONE

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 1 / 31

a1111111111

a1111111111

a1111111111

a1111111111

a1111111111

OPEN ACCESS

Citation: Zhang H, Miyake A, Osborne J, Shah P,

Jonides J (2023) A d factor? Understanding trait

distractibility and its relationships with ADHD

symptomatology and hyperfocus. PLoS ONE

18(10): e0292215. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.

pone.0292215

Editor: Ioanna Markostamou, University of

Hertfordshire, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: July 16, 2023

Accepted: September 11, 2023

Published: October 25, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Zhang et al. This is an open

access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution License, which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided the original

author and source are credited.

Data Availability Statement: All data, code, and

study materials are available at https://osf.io/8j6p4/

.

Funding: This work was supported by the National

Science Foundation [grant number: 1658268]

awarded to the University of Michigan with JJ as

Principal Investigator and the National Institute of

Mental Health (Unique Federal Award Identification

Number (FAIN): R21MH129909) awarded to the

University of Michigan with JJ as Principal

Investigator. The funders had no role in study

disorder (ADHD) but also featured in other psychiatric disorders including anxiety, depres-

sion, and schizophrenia [5–9]. Thus, understanding individual differences in distractibility is

important not only for predicting for whom attention is likely to fail but also for understand-

ing the cognitive underpinnings of psychopathology.

How can we best characterize individual differences in distractibility? Surprisingly, there is

no clear, comprehensive answer to this question yet, because there are multiple different facets

to distractibility. Distractibility can be conceptualized to mean susceptibility to irrelevant stim-

ulation [5], the tendency to have thought intrusions [10], the tendency to experience repetitive

negative thinking [11], or the tendency to engage in mind-wandering [12]. Oftentimes, how-

ever, these different conceptualizations of distractibility have been studied in isolation; in fact,

most existing studies on this topic consider only a single aspect of distractibility (e.g., external

distraction) and often assess it with a single measure. Moreover, studies on distractibility are

often conducted with underpowered samples (most often with just convenience samples of

college students) and without replication of the results. For these reasons, it is yet unclear

whether and to what extent these constructs reflect different facets of distraction.

The current study used an individual-differences approach to establish a structure of dis-

tractibility. We assessed different facets of distractibility in two large samples (one drawn from

college students and the other drawn from the broader community) by administering a large

battery of self-report measures, each facet represented by multiple questionnaires. Using con-

firmatory factor analyses, we specified how these constructs are empirically related to one

another at the latent level. Then, we applied our resulting model to understand individual dif-

ferences in ADHD symptomatology as well as hyperfocus, a prolonged state of concentration

often observed among individuals with high levels of ADHD symptomatology [13]. As such,

the current study sheds new light not only on the factor structure of individual differences in

different types of distractibility but also on the nature of distractibility associated with ADHD.

Different forms of distraction

The term “distraction” is commonly used to refer to irrelevant percepts in the external envi-

ronment, such as irrelevant visual stimuli (e.g., a visually salient object unrelated to a current

visual search) and irrelevant auditory stimuli (e.g., irrelevant speech). The study of external

distraction has a long and distinguished history in the field of psychology featuring experimen-

tal manipulations of external stimulation [14–16]. Furthermore, the notion of distractibility as

an important individual-differences factor has long been proposed, but “distractibility” in

these early studies almost exclusively refers to distraction by external stimulation [5, 17–20].

However, external stimulation is likely not the only source of distraction; there is increasing

evidence showing that performance can be hampered by information that is hypothesized to

have an internal origin [21–23]. Three notable constructs that are conceptually distinguishable

from external distraction are (a) thought intrusions, (b) repetitive negative thinking, and (c)

mind-wandering.

Thought intrusion is a common experience. Studies have found that over 80% of healthy

individuals experience some form of intrusive thoughts [24]. The contents of these thoughts

are often negative (e.g., an unpleasant memory) and sometimes even abhorrent and disgusting

(e.g., violence against someone). Though typically studied from a psychopathology perspective,

thought intrusions constitute a form of cognitive distraction because they interrupt the flow of

thought and capture mental capacity. As a result, one of the hallmarks of thought intrusions is

that they interfere with ongoing task performance [25].

Repetitive negative thinking is defined as “repetitive thinking about one or more negative

topics that is experienced as difficult to control” [26, p.193]. Two common forms of repetitive

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 2 / 31

design, data collection and analysis, decision to

publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared

that no competing interests exist.

negative thinking are rumination, defined as past-oriented persistent dwelling on causes and

consequences of one’s distress [27], and worry, defined as future-oriented repetitive thinking

about potential threats, uncertainties, and risks [28, 29]. Both rumination and worry are asso-

ciated with difficulty concentrating and low task performance [21, 23, 30]. Although repetitive

negative thinking and thought intrusions share many similarities (e.g., unpleasant, distracting,

and uncontrollable), there are some fine-grained differences between them. Clark and Rhyno

[24] suggest that repetitive negative thinking may represent a more persistent form of cogni-

tive interference, whereas thought intrusions may be more sudden, undirected, and somewhat

unexpected (akin to a “mental flash”).

The term mind-wandering was used by Smallwood and Schooler [12] to describe a collec-

tion of terms that all entail a spontaneous shift of attention away from a task toward “unrelated

inner thoughts, fantasies, feelings, and other musings” (p. 946). The term has since been

employed to characterize a diverse array of mental phenomena, including intentional or delib-

erate forms of mind-wandering (as opposed to unintentional or spontaneous), and unguided

thoughts that may arise even in the absence of any task [31]. Considering the expansive usage

of the term, not all mental phenomena grouped under it can be deemed as distractions. In the

study we report here, we narrows its focus on the facet of mind-wandering that is spontaneous

and unrelated to the task at hand. Under this definition, mind-wandering constitutes a form of

distraction in many cognitive tasks [32].

In conception, for several reasons, mind-wandering is not considered as simply repetitive

negative thinking or thought intrusion. First, mind-wandering is not necessarily negative or

unpleasant. For example, during a lecture, students may find themselves thinking about unre-

lated things such as their plans for the weekend. While these thoughts disrupt attention to the

lecture, they may be quite pleasant, interesting, and constructive for other purposes [33]. Sec-

ond, mind-wandering does not necessarily involve recurrent, repetitive, or cyclical mental

content [34]. A person may meander from topic to topic during an episode of mind-wander-

ing; different mind-wandering episodes may also involve wholly different topics. Third, indi-

viduals are often unaware of their mind-wandering state [35] whereas repetitive negative

thinking and thought intrusion are often associated with conscious appraisals and attempts to

resist [36].

The relationships among facets of distractibility

We have reviewed several constructs that capture different aspects of how easily a person can

be distracted, but how exactly are they related to each other? That is, if a person is prone to one

type of distraction, are they also prone to other types of distractions? To our knowledge, no

prior work has examined the relationships among all of these constructs simultaneously within

a single study. Without an empirical assessment of their relationships, we run the risk of jingle-

jangle fallacies [37, 38]. In the jingle fallacy, the same term is used to refer to distinct con-

structs, whereas in the jangle fallacy, different terms are used to refer to the same construct.

At one extreme, for example, external distraction, thought intrusions, repetitive negative

thinking, and mind-wandering may be completely separable and not share anything in com-

mon, thus making the practice of calling them all instances of distraction highly misleading

(representing a case of the jingle fallacy). At the other extreme, they may be completely redun-

dant constructs (thus, representing a case of the jangle fallacy) so there is no need to differenti-

ate among them.

Both of these accounts are unlikely, however, in light of previous studies examining the

relationship between external distraction and mind-wandering, which have shown that they

are correlated yet distinct constructs [39, 40]. For example, Unsworth and McMillan [40]

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 3 / 31

obtained self-reports of external distraction and mind-wandering by presenting thought

probes as participants completed laboratory tasks. Using confirmatory factor analysis, they

found that a two-factor model consisting of an external distraction factor and a mind-

wandering factor fit statistically better than combining them into one factor (i.e., constraining

their correlation to 1), although there was a sizable correlation between the two factors

(r = .44). While these studies show that external distraction and mind-wandering demonstrate

some overlap, they did not distinguish mind-wandering from similar constructs like thought

intrusions and repetitive negative thinking. Instead, “mind-wandering” was used generally to

represent distraction by internal stimuli [40].

Indeed, the practice of partitioning distraction into an external-internal dichotomy is preva-

lent in the literature [41–44]. By this account, thought intrusions, repetitive negative thinking,

and mind-wandering should be highly correlated (if not redundant) and load onto the same fac-

tor because, in conception, they all reflect distraction by internal thoughts. However, studies

have shown that mind-wandering can be experienced as quite pleasant even though it may

reduce task performance [33]. Furthermore, several studies have shown that self-reported

mind-wandering tendency is only moderately correlated with self-reported thought intrusions

(rs = .24 to.36 [45, 46]). These results suggest that what is perceived as mind-wandering might

not be perceived as repetitive negative thinking (or thought intrusion). If so, then a simple exter-

nal-internal dichotomy may not adequately capture the relationships among these constructs.

A general distractibility factor?

The studies reviewed above suggest that external distraction, thought intrusions, repetitive

negative thinking, and mind-wandering may have some underlying commonality but also

demonstrate some separability, a pattern similar to that observed in individual differences

studies of executive functions [47, 48]. This pattern of “unity and diversity” provides a useful

way to think about the factor structure of distractibility. It may be plausible to assume that the

correlations among various forms of distraction reflect an overarching trait that governs a per-

son’s general tendency to be distracted by irrelevant information. Additionally, there might be

additional factors that determine a person’s vulnerability to a specific form of distraction. This

unity/diversity specification of distractibility seems to map well onto existing theories [9, 49–

53]. For example, it has been argued that a person’s domain-general working memory capacity

plays an overarching role in maintaining the task goal and avoiding distractions [51]. Other

specific factors, such as current life concerns, play an additional role in determining the occur-

rence of mind-wandering.

Several recent studies have attempted to establish a general trait of distractibility, most nota-

bly those conducted by Forster and Lavie [54, 55]. These authors created a laboratory task that

was designed to parallel external distractions in daily life. In this task, external distraction was

introduced by the presence of irrelevant cartoon figures in a visual search task. The dependent

measure was a distractor-interference score based on the RT difference between distractor-

absent and distractor-present conditions. Forster and Lavie [54, 55] found that the distractor

interference score was correlated with a self-reported measure of mind-wandering (r = .26

(Exp. 1) and r = .38 (Exp. 3)) and with a self-reported measure of childhood ADHD symptoms

(r = .32 (Exp. 1) and r = .32 (Exp. 2)). Based on these results, Forster and Lavie [55] suggested

that a general factor exists that “confers vulnerability to irrelevant distraction across the gen-

eral population” (p. 209). However, a subsequent study failed to replicate those findings [56].

Of particular concern is the low internal consistency of the cartoon-distraction task (.08—.26

as reported in [56]), which suggests that the task might not reliably capture individual differ-

ences in external distractibility.

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 4 / 31

In another study, Hobbiss et al. [57] assessed the degree to which people experience external

distractions and mind-wandering while engaging in a wide range of daily life activities. Hob-

biss et al. [57] found that self-reports of external distraction were correlated with self-reports

of mind-wandering and that these measures loaded on a single factor. However, because there

were seven external distraction items and a single mind-wandering item, the resulting single

factor still largely captured external distraction rather than what is common to external dis-

traction and mind-wandering.

Overall, although these recent studies provided some initial evidence for a potential higher-

order distractibility factor, the evidence is still limited. Moreover, in any of the studies just

reviewed here, two other forms of distraction—thought intrusions and repetitive negative

thinking—were not considered. Thus, it is necessary to further investigate the notion of a gen-

eral distractibility factor in a more comprehensive manner.

Linking distractibility to ADHD symptoms and hyperfocus

By extracting a general distractibility factor, one can directly examine how the unity and diver-

sity components of distractibility are related to other individual-differences variables. This is

important because, if a variable of interest is related to multiple correlated factors, this relation-

ship could be driven by just the general component or both the general and the specific com-

ponents. We will take advantage of this feature to understand individual differences in

behavioral symptoms and functional impairments associated with ADHD as well as

hyperfocus.

ADHD symptoms and associated functional impairments. Heightened distractibility

has often been associated with ADHD, defined as an ongoing pattern of inattention and/or

hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development [58]. Though only

about 4% of adults have a formal diagnosis of ADHD, ADHD symptoms are prevalent in the

general population, and a formal diagnosis represents the extreme end of a continuous distri-

bution [59, 60]. ADHD symptoms are associated with functional impairments in various life

domains, including school, work, and interpersonal relationships [61–63]. One of the diagnos-

tic criteria of ADHD is “being often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli (for older adoles-

cents and adults, may include unrelated thoughts)” [58].

What is the nature of the relationship between distractibility and ADHD? The separate

associations between ADHD symptomatology and different forms of distractions may, in

fact, be driven by a single factor that represents an individual’s overall distractibility level.

However, it has been difficult to assess the role of a general factor in explaining ADHD

symptoms because most studies have examined a single form of distraction in relation to

ADHD.

Much of the research on distractibility and ADHD has focused on external distraction [15,

64–66], most likely because “distraction” has traditionally been studied in terms of distraction

by extraneous stimuli. However, separate studies have reported that ADHD symptomatology

is also associated with vulnerability to unwanted intrusive thoughts [67] and spontaneous

mind-wandering [41, 43, 68]. Because different forms of distraction were not considered

simultaneously in these studies, it remains difficult to specify the nature of these observed

correlations.

To what extent are these correlations driven by a common factor that is elevated among

people who have high levels of ADHD symptomatology? Is there anything special between

ADHD and certain forms of distraction beyond general distractibility? One way to address

these questions is to assess whether the relationship between a particular form of distraction

and ADHD still holds after partialing out a possible general factor. If there is a special

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 5 / 31

relationship between a particular form of distraction and ADHD symptoms, one should expect

a meaningful relationship even after controlling for the general factor.

Hyperfocus. The term hyperfocus is used to describe episodes of long-lasting and highly

focused attention that people with high levels of ADHD symptomatology often report [69, 70].

For example, although these individuals often have difficulties paying attention in lectures or

getting things in order, they may find themselves spending hours writing computer programs,

watching TV, and getting engrossed in creative thoughts, to the extent that they completely

lose track of time or forget their personal needs. The term has also attracted huge interest in

the general public with frequent discussions in the media [71–73]. Despite this interest, the

nature of hyperfocus remains poorly understood.

At face value, distractibility and hyperfocus seem to be opposite constructs. The former

entails a state of distracted attention, whereas the latter entails a state of deeply focused atten-

tion. Thus, it seems plausible that distractibility and hyperfocus are not correlated at all or

even negatively correlated. However, there are reasons to believe that distractibility is positively

correlated with hyperfocus. For example, people might be distracted by the same sorts of sub-

jects on which they might tend to hyperfocus. Indeed, hyperfocus is sometimes (but not

always) experienced as negative, such as wasting time on unimportant activities, having diffi-

culty switching to more urgent tasks, and getting “stuck” on small details [13]. If so, then those

who have a higher tendency to engage in hyperfocus might be more easily getting stuck on

subjects that distract them.

An even more intriguing possibility is that hyperfocus is differentially associated with dif-

ferent facets of distractibility. Many instances of hyperfocus experiences include common

qualities such as distorted time perception, failure to attend to the world, ignoring personal

needs, and feelings of total engrossment [13]. These descriptions seem to be antagonistic to

external distraction, which presumably involves engaging in some sensory processing. Simi-

larly, it is plausible to think that one is less capable of remaining in a hyperfocus state if

unwanted thoughts frequently intrude into their current train of thought. In contrast, various

cases of hyperfocus seem to share certain similarities with those of mind-wandering. Mind-

wandering has been viewed as a state of “decoupled attention”, which entails an inward shift of

attention to one’s thoughts and feelings and, as a result, an attenuation of sensory processing

[12, 35].

As such, hyperfocus seems to share some similarities with mind-wandering that are not

shared with other forms of distraction. Then, general distractibility alone may not sufficiently

explain the nature of hyperfocus; it may have more nuanced relationships with specific compo-

nents of distractibility beyond what could be accounted for by a possible general factor.

The current study

There were two primary goals for the current study. The first goal was to understand the rela-

tionships among several popular constructs that tap into distractibility. These constructs

included external distraction, thought intrusions, repetitive negative thinking, and mind-

wandering. To our knowledge, no prior work has examined the relationships among all of

these constructs simultaneously within a single study. Using latent variable analyses, we

assessed the extent to which these constructs, each measured by multiple instruments, are

redundant or separable at the latent level. We also examined the plausibility of extracting a

general factor to capture the commonality underlying these constructs.

The second goal of the study was to apply the model of distractibility derived from the

study to understand the nature of ADHD symptomatology and hyperfocus. We hypothesized

that the putative general factor should account for substantial variance in self-reported

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 6 / 31

symptoms of ADHD and associated functional impairments. But it remains to be seen whether

it has any meaningful relationship with hyperfocus. In addition to examining the role of the

general factor, we were also interested in assessing the role of construct-specific variances in

explaining ADHD symptoms, functional impairments, and hyperfocus. To do so, we exam-

ined how much additional variance the specific distractibility factors could explain over and

above the general factor.

We addressed these two goals from a trait perspective by using questionnaires that measure

individuals’ tendencies to experience various forms of distraction in daily life. Recent studies

suggest that, compared to task-based (behavioral) measures, self-report questionnaire-based

measures tend to converge better and be more associated with real-life behaviors [74–76]. This

does not necessarily indicate that questionnaires are superior to tasks in terms of measuring

distractibility, but establishing the relationships among a range of self-reported real-world dis-

tractions appears to be a reasonable starting point toward a more comprehensive understand-

ing of distractibility. Although specifying the extent of convergence between task-derived and

questionnaire-derived factors of distractibility is an important question, it is beyond the scope

of the present study.

Given the exploratory nature of our research goals, we conducted an internal replication.

Specifically, we collected data from two large samples (Ns = 651 and 569) and used the first

sample for exploratory analyses and the second sample for replication. The two samples dif-

fered in several dimensions, including age, gender distribution, racial composition, and occu-

pation. As such, the results of the second sample help evaluate the replicability of our findings.

Methods

Below we report how we determined our sample size and, all data exclusions and measures in

the study [77]. All data, code, and study materials are available at https://osf.io/8j6p4/.

The procedure was approved by University of Michigan Health Sciences and Behavioral

Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB-HSBS), study ID: HUM00066883. Because both

samples were collected online, written consent could not be obtained from the participants.

Instead, we presented a digital version of the consent form at the beginning of the study and

offered participants to select whether they agree to participate or not. Only those who provided

their agreement were then given access to the full study.

Participants

For both samples, we recruited as many participants as possible given the resources available.

It is worth noting that the study was conducted from October 2020 to February 2021, a period

during which COVID-19 cases were rapidly increasing in the US and in-person testing was

not feasible. Therefore, both samples were recruited using online platforms.

Sample 1. We recruited participants from Prolifc.co that met the following criteria: (a)

between 18 and 35 years of age; (b) residing in the U.S. or Canada; (c) native speakers of

English; (d) with 50–3000 previous submissions and 95%-100% approval rate on the Prolific.

co platform. Participants were compensated with $3.67 for participation. Data were discarded

if participants failed 2 or more out of the 4 attention-check questions interspersed throughout

the questionnaires (n = 5). We further removed data from 1 participant who had a duplicate IP

address. The final sample size was 651, with a mean age of 26.9 (SD = 5.0), 45.3% female,

67.7% white, and 33.9% current students.

Sample 2. We recruited 615 students from the introductory psychology subject pool at

the University of Michigan. Participants completed the study remotely and received partial

course credit for participation. Data were discarded if participants failed 2 or more out of the 4

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 7 / 31

attention check questions (n = 46). Thus, the final sample size was 569, with a mean age of 18.8

(SD = 1.2), 66.3% female, and 56.8% white.

Measures

A battery of commonly used self-report instruments was administered to assess a person’s

vulnerability to external distraction, thought intrusions, repetitive negative thinking, and

mind-wandering. Example items of each measure can be found in Table 1.

Imaginal Processes Inventory—Distractibility (IPI-D). The Imaginal Processes Inven-

tory—Distractibility subscale is a 5-item scale originally designed by Singer and Antrobus [78]

and later refined by Giambra [79] to measure task distractibility with competing stimulation.

Items were rated on a 0 (definitely not true for me) to 4 (very true for me) scale. The final

score was the average score of the 5 items, with a higher score indicating greater vulnerability

to external distraction.

Attentional Style Questionnaire—External (ASQ-E). The Attentional Style Question-

naire measures the ability to maintain attention on task-related stimuli and not to be distracted

by interfering stimuli [80]. The external distraction subscale has 5 items measuring susceptibil-

ity to external interfering stimuli. Items were rated on a 1 (in total disagreement) to 6 (in total

agreement) scale. We administered the full scale but used only the external subscale in data

analysis because the Internal subscale was not designed to measure internal distractions

Table 1. Scale names and example items.

Scale Example Item

External Distraction

Imaginal Processes Inventory—

Distractibility

I find it difficult to concentrate when the TV or radio is on.

Attentional Style Questionnaire—

External

I have trouble concentrating when there is movement in the room I am in.

Attentional Control—Distraction I have difficulty concentrating when there is music in the room around me.

Thought Intrusions

White Bear Suppression

Inventory

There are thoughts that keep jumping into my head.

Thought Control Ability

Questionnaire

It is very easy for me to stop having certain thoughts.

Thought Suppression Inventory I have thoughts which I would rather not have.

Repetitive Negative Thinking

Perseverative Thinking

Questionnaire

The same thoughts keep going through my mind again and again.

Penn State Worry Questionnaire I am always worrying about something.

Ruminative Response Scale—

Brooding

[How often do you] think “What am I doing to deserve this?”

Mind-Wandering

Imaginal Processes Inventory—

Mind-wandering

During a lecture or speech, my mind often wanders.

Mind-wandering—Spontaneous I find my thoughts wandering spontaneously.

Daydreaming Frequency Scale I lose myself in active daydreaming [frequency option].

ADHD-related Scales

Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale How often do you have problems remembering appointments or obligations?

Functional Impairments [ADHD symptoms affect my ability to function] In my work or occupation.

Adult Dispositional Hyperfocus

Questionnaire

Generally, when I am busy doing something I enjoy or something that I am

very focused on, I tend to completely lose track of time.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215.t001

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 8 / 31

specifically (e.g., “It is hard for me to stay on one activity for a whole hour.”). The final score

was the average score of the 5 items in the external subscale. A higher score indicated greater

vulnerability to external distraction.

Attentional Control—Distraction (AC-D). The Attentional Control—Distraction scale

is a 4-item scale measuring susceptibility to external distraction [81]. Items were rated on a 1

(almost never) to 5 (always) scale. The final score was the average of the 4 items, with a higher

score indicating greater vulnerability to external distraction.

White Bear Suppression Inventory (WBSI). The White Bear Suppression Inventory is a

15-item scale measuring the control of thoughts [82]. Items were rated on a 1 (strongly dis-

agree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale. The final score was the average score of all items, with a

higher score indicating greater vulnerability to thought intrusions.

Thought Control Ability Questionnaire (TCAQ). The Thought Control Ability Ques-

tionnaire is a 20-item scale measuring one’s ability to control unwanted thoughts [83]. Items

were rated on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale. To make the directionality of

this scale consistent with that of the other scales, we reversed the original scoring scheme so

that a higher score indicated worse thought control ability. The final score was the average

score of all items.

Thought Suppression Inventory (TSI). The Thought Suppression Inventory is an

18-item scale measuring thought suppression [84]. Items were rated on a 1 (strongly disagree)

to 5 (strongly agree) scale. Previous research has identified three subscales: intrusion, suppres-

sion attempt, and effective suppression [85]. We administered the full scale but excluded items

in the suppression attempt subscale from data analysis because a suppression attempt can be

either successful or unsuccessful, making it an ambiguous measure of thought suppression.

The final score was the average score of all the intrusion items and the reverse-coded effective

suppression items. A higher score indicated greater thought intrusion.

Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire (PTQ). The Perseverative Thinking Question-

naire is a 15-item clinical measure of the extent to which individuals experience repetitive,

uncontrollable, and attention-consuming thoughts [86]. Items were rated on a 0 (never) to 4

(almost always) scale. The final score was the average score of the 15 items. A higher score

indicated a greater tendency to engage in repetitive negative thinking.

Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ). The Penn State Worry Questionnaire is a

16-item clinical measure of excessive and uncontrollable worry [87]. Items were rated on a 1

(not at all typical of me) to 5 (very typical of me) scale. The final score was the average of the

16 items, with a higher score indicating a greater tendency to worry.

Ruminative Response Scale—Brooding (RRS-B). The Ruminative Response Scale

(short form) is a 10-item clinical measure of the reflection and brooding aspects of rumina-

tion [88]. The reflection subscale and brooding subscales each have 5 items. Participants

were asked to read each item and indicate the extent to which they think or do each one

when they feel down, sad, or depressed. Items were rated on a 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost

always) scale. Previous research has shown that the brooding subscale is more representative

of maladaptive thinking whereas the reflection subscale captures a less maladaptive form of

rumination [88]. Thus, the brooding subscale was used as the manifest variable of repetitive

negative thinking, rather than the full scale. The final score was the average of the 5 items in

the brooding subscale, with a higher score indicating a greater tendency to engage in

brooding.

Imaginal Processes Inventory—Mind-wandering (IPI-MW). The Imaginal Processes

Inventory—Mind-wandering subscale is a 6-item scale proposed by [79] using items originally

from the Imaginal Processes Inventory [78]. The IPI-MW measures task-unrelated thoughts

during tasks. Items were rated from 0 (definitely not true for me) to 4 (very true for me). The

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 9 / 31

final score was the average of the 6 items, with a higher score indicating a greater tendency to

engage in mind-wandering.

Mind-wandering—Spontaneous (MW-S). The Mind-wandering—Spontaneous scale is a

4-item scale measuring spontaneous mind-wandering [81]. Items were rated on a 1 (rarely) to

7 (a lot) scale except for the 3rd item (“It feels like I don’t have control over when my mind

wanders.”), which was rated on a 1 (almost never) to 7 (almost always) scale. The final score

was the average of the 4 items, with a higher score indicating a greater tendency to engage in

spontaneous mind-wandering.

Daydreaming Frequency Scale (DDFS). The Daydreaming Frequency Scale is a 13-item

scale originally from the Imaginal Processes Inventory [78]. The original scale has 12 items,

but according to the factor analysis by [79], an additional item (“I tend to get pretty wrapped up

in my daydreaming.”) should belong to this scale. Items were rated on a 1-to-5 scale. The final

score was the average of all items, with a higher score indicating a greater tendency to engage

in daydreaming.

Adult ADHD Self-report Scale. The Adult ADHD Self-report Scale is a popular 18-item

clinical measure for screening adults with ADHD [89]. The 18 items correspond to the eighteen

criteria used to diagnose ADHD. Each question was rated on a 5-point scale from 0 (Never) to

4 (Very often). The scale uses a dichotomous-scoring system such that responses to each ques-

tion are dichotomized into whether a particular symptom is present or not. For example, for

the question “How often do you have problems remembering appointments or obligations?”, a

response of “sometimes”, “often”, or “very often” indicates the presence of the symptom,

whereas a response of “never” and “rarely” indicates the absence of the symptom. The total

score was calculated by counting all positive symptoms, yielding a theoretical range of 0–18.

ADHD functional impairment questionnaire. The functional impairment questions

were selected from the Current Symptoms Scale developed by [90]. The questionnaire includes

10 questions regarding functional impairment in ADHD. The purpose of this scale is to under-

stand how ADHD symptoms potentially impact different areas of an individual’s life (i.e.,

school, work, relationships). These questions were presented immediately following the Adult

ADHD Self-report Scale. Participants were asked to indicate “To what extent do the problems

you may have selected on the previous questionnaire interfere with your ability to function in

each of these areas of life activities?” Each item has the following response options: “never/

rarely”, “sometimes”, “often”, and “very often”. These items were rated on a 0-to-3 scale. The

final score was the average score of the 10 items, with a higher score indicating greater func-

tional impairment.

Adult Dispositional Hyperfocus Questionnaire. The adult dispositional hyperfocus

questionnaire is a 12-item scale measuring one’s tendency to experience hyperfocus [13], a

state of heightened, focused attention that individuals with ADHD frequently report. Each

item has the following response options: “never”, “1–2 times every 6 months”, “1–2 times per

month”, “once a week”, “2–3 times a week”, and “daily”. These items were rated on a 1-to-6

scale (1 corresponding to “never” and 6 corresponding to “daily”). The final score was the

average rating of all items, with a higher score indicating a greater tendency to engage in

hyperfocus.

Procedure

Questionnaires were presented to the participants in a pseudo-random order such that those

of the same category were always presented together. The presentation order within each cate-

gory was randomized for each participant, except that the Functional Impairment Question-

naire was always presented immediately after the Adult ADHD Self-report Scale.

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 10 / 31

Data analysis

Our data analytic plan consisted of two main steps. First, we conducted a series of confirma-

tory factor analyses to explore the factor structure of distractibility. Second, in structural equa-

tion modeling, we related our models of distractibility to individual differences in ADHD

symptoms, functional impairments, and hyperfocus. Throughout the analyses, we used Sample

1 for exploratory purposes and Sample 2 for replication.

Data analysis was conducted in the R environment. Latent factor modeling was conducted

using the lavaan package [91] with robust maximum likelihood, which produces the Satorra-

Bentler χ

2

statistic (S-B χ

2

) for the overall model fit. A non-significant χ

2

value is often desir-

able, but with a large sample, even trivial mis-specifications can produce a significant result.

For this reason, we supplemented the χ

2

statistic with additional fit indices, such as the com-

parative fit index (CFI), the robust root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and

the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). By convention, the fit of a model is

deemed acceptable when CFI > .90, RMSEA < .08, and SRMR < .08. For RMSEA, we also

report the 90% confidence interval (90% CI) to assess how close it is to the boundary of misfit.

For model comparison, we report the S-B χ

2

difference test and the Bayes Factors (BFs)

derived from the BIC approximation [92]. Following recommendations by Raftery [93], we

consider 1 < BF <= 3 to be weak supporting evidence, 3 < BF <= 20 to be positive supporting

evidence, 20 < BF <= 150 to be strong supporting evidence, and BF > 150 to be very strong

supporting evidence. Conversely, we consider 1/3 <= BF < 1 to be weak evidence against,

1/20 <= BF < 1/3 to be positive evidence against, 1/150 <= BF < 1/20 to be strong evidence

against, and BF < 1/150 to be very strong evidence against.

Results

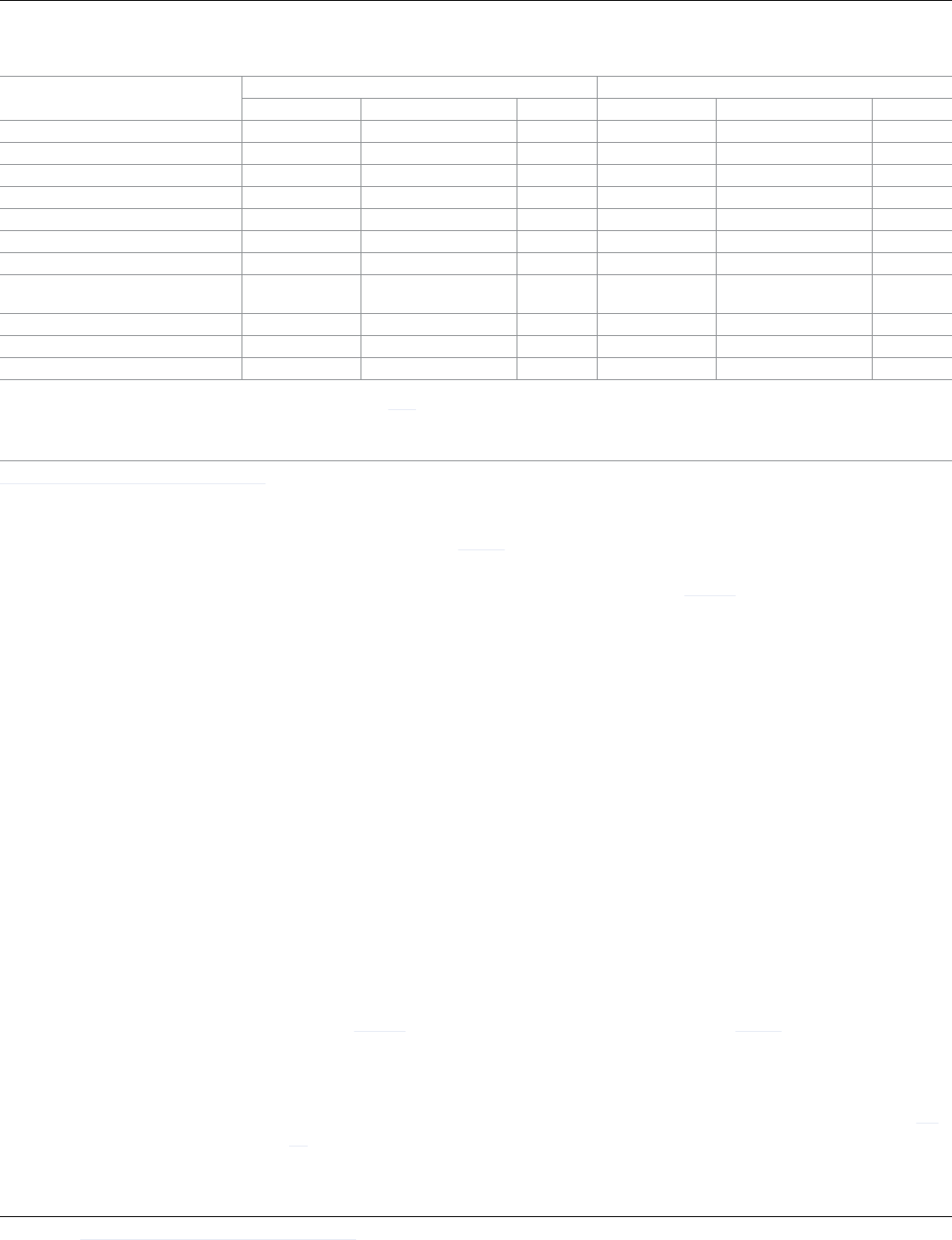

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for all measures for both Samples 1 and 2. Overall, all

measures had satisfactory reliability values and normal levels of skewness and kurtosis in both

samples. Compared to Sample 1, the standard deviations associated with Sample 2 were consis-

tently lower, suggesting that Sample 2 was more homogeneous, which is consistent with the

fact that they were college students enrolled in an introductory psychology course.

The full correlation matrix is presented in Fig 1. The correlations for Sample 1 are presented

below the diagonal, whereas those for Sample 2 are presented above the diagonal. As is clear

from Fig 1, the patterns of the correlations were generally comparable for the two samples.

Goal 1: Understanding the relationships among different facets of

distractibility

Exploratory analyses with Sample 1. The baseline measurement model consisted of

External Distraction, Thought Intrusions, Repetitive Negative Thinking, and Mind-wandering,

with each factor represented by three scales. Although this model produced a good fit

(χ

2

(48) = 157.33, p < .001; CFI = .98; RMSEA = .06 [.05, .08]; SRMR = .029; BIC = 14,948),

we modified this model in two ways based on substantive concerns [94 p.310].

First, as shown in Fig 2, the factors Thought Intrusions and Repetitive Negative Thinking

had a near-perfect correlation, and they also had similar relationships with the other factors in

the model (the model’s full structure can be found in S1 Fig). Thus, to avoid redundancy in the

model structure, we combined Thought Intrusions, Repetitive Negative Thinking into a single

factor named Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts. This move aligns with recommendations by Kline

[94], who stressed that respecification in CFA should be guided as much as possible by sub-

stantive considerations. Given the large sample sizes of the current study and the resulting

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 11 / 31

statistical power, even trivial differences may become highly significant. Here, an r = .95

means that the two factors shared about 85% to 90% of the variance (i.e., only *10% and

*15% of the unique variance left). If these highly correlated constructs were kept separate, the

meaning of a possible general factor would be highly biased (essentially adding a duplicate

indicator). Although some details differ, some previous latent-variable analysis studies have

merged some latent variables on the basis of such substantive considerations [95–98].

Second, we inspected the modification indices (MI) of the model, which suggested that

allowing the residual of the TCAQ and that of the TSI to correlate with each other would pro-

duce the largest improvement in model fit (MI = 62.82). This suggestion makes sense, given

that the TCAQ and the TSI shared many similarly worded items (e.g., “There are some thoughts

that enter my head without me being able to avoid it” in the former and “Some unwanted

thoughts enter my mind without me being able to do anything about it” in the latter; original

items are available at https://osf.io/8j6p4/). Thus, we added this error covariance parameter to

capture the wording similarity.

The resulting three-factor model is presented in Fig 3A. Loadings and factor correlations for

this sample (Sample 1) are indicated in bold fonts. The fit of the model was good, χ

2

(50) = 172.73,

p < .001; CFI = .98; RMSEA = .07 [.06, .08]; SRMR = .030; BIC = 14,953. The observed measures

were generally loaded strongly onto their respective factors (zs >= 28.72, ps < .001). The three

factors were also significantly correlated with each other (rs >= .53, zs >= 14.49, ps < .001). The

model also indicated a nontrivial correlation between the error terms of the TCAQ and the TSI

(r = .47, z = 9.72, p < .001). A re-inspection of the modification indices did not suggest further

alternations that would appreciably improve model fit.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for all measures analyzed in the current study.

Scale Name Sample 1 Sample 2

mean SD skew kurtosis alpha mean SD skew kurtosis alpha

External Distraction

Imaginal Processes Inventory—Distractibility 2.30 0.92 -0.29 -0.35 0.85 2.45 0.79 -0.09 -0.26 0.78

Attentional Style Questionnaire—External 3.43 1.06 0.00 -0.10 0.81 3.58 0.99 0.03 -0.40 0.78

Attentional Control—Distraction 2.76 1.04 0.19 -0.84 0.88 3.04 0.97 0.03 -0.83 0.84

Thought Intrusions

White Bear Suppression Inventory 3.56 0.77 -0.57 0.29 0.92 3.54 0.69 -0.26 -0.15 0.90

Thought Control Ability Questionnaire 3.22 0.83 -0.15 -0.48 0.95 3.19 0.71 -0.02 -0.51 0.93

Thought Suppression Inventory 3.20 0.80 -0.05 -0.25 0.91 3.16 0.69 0.16 -0.41 0.89

Repetitive Negative Thinking

Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire 2.11 0.96 -0.22 -0.46 0.97 2.16 0.80 0.04 -0.36 0.95

Penn State Worry Questionnaire 3.37 0.98 -0.27 -0.79 0.96 3.56 0.86 -0.37 -0.55 0.95

Ruminative Response Scale—Brooding 2.39 0.78 0.19 -0.80 0.85 2.41 0.72 0.28 -0.76 0.80

Mind-Wandering

Imaginal Processes Inventory—Mind-wandering 2.15 0.95 0.03 -0.67 0.89 2.17 0.87 0.17 -0.71 0.86

Mind-wandering—Spontaneous 4.29 1.50 -0.29 -0.56 0.91 4.21 1.35 -0.03 -0.41 0.88

Daydreaming Frequency Scale 3.04 0.94 -0.04 -0.73 0.96 3.00 0.86 0.01 -0.72 0.95

ADHD-related Constructs

Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale 5.91 4.50 0.60 -0.44 0.86 7.02 4.19 0.35 -0.56 0.82

ADHD Functional Impairment 0.84 0.63 0.73 0.19 0.90 0.86 0.57 0.63 0.08 0.86

Dispositional Hyperfocus 3.44 1.10 0.01 -0.65 0.92 3.53 1.04 -0.01 -0.67 0.91

Note. SD = Standard Deviation

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215.t002

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 12 / 31

We also tested a two-factor model in which Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts and Mind-wan-

dering were combined into one factor named Internal Distraction, as well as a single-factor

model in which all three factors were combined into a single factor. In both models, the afore-

mentioned error correlation between the TCAQ and the TSI was included. However, both

models resulted in very poor model fit. Specifically, the fit of this two-factor model was appre-

ciably worse compared to the three-factor model as shown in Fig 3A, Δχ

2

(2) = 201.96,

p < .001; BF < 1/1000 (very strong evidence against). And the fit of the single-factor model

was even worse compared to the two-factor model, Δχ

2

(1) = 290.00, p < .001; BF < 1/1000

(very strong evidence against).

The results so far indicate that External Distraction, Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts, and

Mind-wandering were substantially correlated constructs. Therefore, we introduced a higher-

order common factor d to capture their shared variance, as shown in Fig 3B. We chose the let-

ter d for this general factor to echo other general factors that have been proposed in the litera-

ture, such as the general psychopathology factor p [99] and general intelligence factor g [100].

Fig 1. A correlation matrix for all measures. Sample 1: below the diagonal line. Sample 2: above the diagonal line.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215.g001

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 13 / 31

This change in model structure from correlated factors to a higher-order common factor does

not alter the model fit. The first-order loadings remained the same as in the correlational

model. The three first-order factors (External Distraction, Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts, and

Mind-wandering) were all significantly loaded onto d (zs >= 19.03, p < .001).

To quantify the magnitude of the shared variance, we calculated the coefficient omega at

Level 2 (ω

L2

), which indicates the proportion of variance among the first-order factors attribut-

able to d. We found that ω

L2

= .83, indicating that d explained 83% of the total variance in

External Distraction, Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts, and Mind-wandering. The variances in the

first-order factors that could not be explained by d were captured by their respective residual

terms (.57, .36, and .28, respectively, as shown in Fig 3B). These residual terms were all signifi-

cantly different from zero (zs >= 4.48, p < .001). Thus, although d captured a substantial

amount of shared variance, there were still some construct-specific variances left.

We then compared the strength of the second-order loadings on d. To do so, we imposed

a series of equality constraints on the second-order loadings of the model. Constraining all

three factors to load equally on d substantially worsened model fit, Δχ

2

(1) = 19.19, p < .001;

BF = 1/212.43 (very strong evidence against). Thus, the three second-order loadings were

not equal. To better specify the source of this non-equivalence of the d loadings, we con-

ducted pairwise comparisons by constraining two of the loadings to be equal at each time

and compared it to the model without the constraints. Constraining Mind-wandering and

External Distraction to load equally on d substantially worsened model fit, Δχ

2

(1) = 14.63,

p < .001; BF < 1/1000 (very strong evidence against). Constraining Unwanted Intrusive

Thoughts and External Distraction to load equally on d also substantially worsened model fit,

Δχ

2

(1) = 14.47, p < .001; BF = 1/26.19 (strong evidence against). But constraining Unwanted

Fig 2. Latent correlations among external distraction, thought intrusions, repetitive negative thinking, and mind-

wandering. The correlation between Thought Intrusions and Repetitive Negative Thinking was close to 1 in both

samples.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215.g002

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 14 / 31

Intrusive Thoughts and Mind-wandering to load equally on d did not worsen model fit,

Δχ

2

(1) = .67, p = .41; BF = 16.17 (positive evidence in favor of). These results indicate that

the loading of External Distraction on d was relatively weaker (albeit still significant) com-

pared to those of Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts and Mind-wandering.

Fig 3. Correlational and general factor models of distractibility. Fully standardized estimates are shown, with bold fonts

indicating Sample 1 and regular fonts indicating Sample 2. IPI-D: Imaginal Processes Inventory-Distractibility; ASQ-E: Attentional

Style Questionnaire-External; AC-D: Attentional Control-Distraction; PTQ: Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire; PSWQ: Penn

State Worry Questionnaire; RRS-B: Ruminative Response Scale-Brooding; WBSI: White Bear Suppression Inventory; TCAQ:

Thought Control Ability Questionnaire; TSI: Thought Suppression Inventory (revised); IPI-MW: Imaginal Processes Inventory-

Mind-wandering; MW-S: Mind-wandering-Spontaneous; DDFS: Daydreaming Frequency Scale.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215.g003

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 15 / 31

Replication with Sample 2. After the explorations of various models using Sample 1 as

described above, we tested whether the results could be replicated using Sample 2. As shown in

Fig 2, the correlation between Thought Intrusions and Repetitive Negative Thinking was again

close to 1 (r = .92) and thus the two factors should be combined. Modification indices again

suggested that adding the residual correlation between TCAQ and TSI would produce the larg-

est improvement in model fit (MI = 31.84). Thus, adding the error covariance is also justified.

The same three-factor model as shown in Fig 3A resulted in a good model fit, χ

2

(50) =

163.24, p < .001; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .07 [.06, .08]; SRMR = .041; BIC = 12,526. The loadings

and factor correlations for the Sample 2 data are shown in regular font below those for the

Sample 1 data. Similar to Sample 1, the factor loadings (zs >= 24.88, ps < .001) and factor cor-

relations (rs >= .32, zs >= 7.37, ps < .001) were all significant. Furthermore, the Sample 2 data

did not support a two-factor model, Δχ

2

(2) = 296.73, p < .001; BF < 1/1000 (very strong

evidence against), or a one-factor model, Δχ

2

(1) = 893.97, p < .001; BF < 1/1000 (very strong

evidence against).

For the higher-order model as shown in Fig 3B, the three first-order factors were all signifi-

cantly loaded onto d (zs >= 8.92, p < .001). The ω

L2

of d was.77, indicating that d explained

77% of the total variance in External Distraction, Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts, and Mind-

wandering (83% in Sample 1). In addition, the residual terms of External Distraction,

Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts, and Mind-wandering were all significantly different from zero

(zs >= 2.94, p <= .003).

Comparisons of the second-order loadings once again show that External Distraction was

relatively weakly (albeit still significantly) loaded onto d. Specifically, constraining all three sec-

ond-order loadings to be equal substantially worsened model fit, Δχ

2

(1) = 47.95, p < .001;

BF < 1/1000 (very strong evidence against). Constraining Mind-wandering and External Dis-

traction to load equally on d substantially worsened model fit, Δχ

2

(1) = 40.98, p < .001;

BF < 1/1000 (very strong evidence against). Constraining Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts and

External Distraction to load equally on d substantially worsened model fit, Δχ

2

(1) = 28.03,

p < .001; BF < 1/1000 (very strong evidence against). But constraining Unwanted Intrusive

Thoughts and Mind-wandering to load equally on d did not worsen model fit, Δχ

2

(1) = 1.91,

p = .17; BF = 9.15 (positive evidence in favor of).

Overall, all of the above results based on Sample 2 were highly consistent with those based

on Sample 1.

Measurement invariance. Next, we conducted a measurement invariance analysis to eval-

uate the replicability of the model at the parameter level (i.e., beyond the global model struc-

ture). Measurement invariance analysis involves testing the equivalence of models in

independent samples to assure that the same constructs are being assessed in each sample. Spe-

cifically, a series of cross-group equality constraints are incrementally added to a multiple-

group confirmatory factor analysis model. Four levels of invariance are typically tested: (a)

configural invariance (i.e., equal model structure across samples), (b) metric invariance (i.e.,

equal loadings across samples), (c) scalar invariance (i.e., equal intercepts across samples), and

(d) residual invariance (i.e., equal residuals across samples). If the model with new constraints

does not fit appreciably worse than the model without those constraints, then the invariance

hypothesis is retained.

Currently, there is no consensus on the appropriate criteria to assess invariance. We made

our decisions based on multiple fit indices, including ΔCFI, ΔRMSEA, ΔSRMR, and Bayes

Factors. Δχ

2

tests were not recommended as a criterion to assess invariance when the sample

size is large [94]. Thus, they were reported for completeness but not considered in the assess-

ment of invariance. All models in this analysis were identified using the effect-coding

method [101].

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 16 / 31

The results, as shown in Table 3, indicate that the higher-order model passed all four levels

of invariance. This indicates that the scales measured the same factors (configural) with the

same unit of measurement (loadings), same origin (intercepts), and the same precision (resid-

uals). Note that the Bayes Factor for scalar invariance was 1/2.46, indicating weak evidence

against scalar invariance over metric invariance. However, considering that ΔCFI, ΔRMSEA,

and ΔSRMR were all well below common cut-off values [94], we retained scalar invariance. It

should be noted that metric invariance may be considered particularly important in invariance

testing because it ensures that relations among the factors and measured variables are similar

across samples. Overall, these results indicate that the higher-order general distractibility

model was highly replicable at the parameter level.

Goal 2: Linking distractibility to ADHD symptoms and hyperfocus

After establishing the higher-order model of distractibility, we proceeded with our next goal:

applying the model to understand individual differences in ADHD symptoms and hyperfocus.

Again, we used Sample 1 for exploratory analyses and Sample 2 for replication.

Exploratory analyses with Sample 1. First, we explored how well d alone could account

for variances in ADHD symptoms, ADHD functional impairments, and hyperfocus. We built

a model in which the three variables were simultaneously regressed onto d. A schematic illus-

tration of the model is given in Fig 4A. The fit of the model was good, χ

2

(83) = 320.35, p <

.001; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .07 [.06, .08]; SRMR = .041; BIC = 19,528. Table 4 shows the struc-

tural paths associated with d. As shown in the table, a higher d was strongly related to a higher

level of ADHD symptomatology and greater functional impairments. Notably, d was also posi-

tively related to hyperfocus, such that a higher d (i.e., higher general distractibility) was associ-

ated with a stronger tendency to engage in hyperfocus.

Next, we explored whether any diversity aspects of distractibility could explain any addi-

tional variance. To do so, we built models in which the three variables were regressed onto the

residual variances of External Distraction, Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts, and Mind-wandering

in addition to d. These residual variances were construct-specific variances in each specific

form of distraction that were not explained by d (see Fig 3B). To use residual variance as a pre-

dictor, we created a latent factor to capture the residual variance in each group factor following

instructions from [102]. These models are shown in Fig 4B–4D. The structural paths associated

with the residual factor, therefore, test the explanatory power of construct-specific variance

that is unrelated to d. Note that this procedure had to be conducted separately for each first-

level factor because regressing on all residuals simultaneously leads to non-identification issues

Table 3. Measurement invariance analysis of the general distractibility model.

Model Comparison χ

2

df Δχ

2

CFI RMSEA [90% CI] SRMR BF

1. configural invariance 336.18 100 .98 .07 [.06, .07] .033

2. metric invariance 2 vs. 1 366.11 111 28.53** .97 .07 [.06, .07] .045 > 1000

3. scalar invariance 3 vs. 2 446.15 122 91.76*** .97 .07 [.06, .08] .050 1/2.46

4. residual invariance 4 vs. 3 474.52 138 28.75* .97 .07 [.06, .07] .050 > 1000

Note. The Δχ

2

column shows the Satorra-Bentler-adjusted Δχ

2

difference test, which is a function of two standard (not robust) χ

2

statistics.

* p < .05,

** p < .01,

*** p < .001.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215.t003

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 17 / 31

due to linear dependency (for a technical discussion of the issue, see Zhang et al. [103, p.536];

for a previous example of separately testing the residuals, see Berkowitz and Stern [104]).

The model shown in Fig 4B used the residual of External Distraction as an additional pre-

dictor. The model had a good fit, χ

2

(80) = 302.00, p < .001; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .07 [.06, .08];

SRMR = .036; BIC = 19,527. The key results are summarized in Table 4. External Distraction

residual was not significantly associated with ADHD symptoms or functional impairments. A

negative relationship emerged between the residual of External Distraction and hyperfocus,

such that a higher susceptibility to external distraction was associated with a weaker hyperfo-

cus tendency after controlling for d.

The model shown in Fig 4C used the residual of Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts as an addi-

tional predictor. The model had a good fit, χ

2

(80) = 316.49, p < .001; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .07

[.06, .08]; SRMR = .040; BIC = 19,542. The results, summarized in Table 4, show that

Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts residual did not significantly explain additional variance in any

of the variables.

Fig 4. Schematic illustrations of models testing how the unity and diversity aspects of distractibility were related to ADHD

symptoms, functional ADHD impairments, and hyperfocus. Panel A shows a model that tests how well d alone could account for

variances in ADHD symptoms, functional impairments, and hyperfocus. The models in panels B-D test whether External

Distraction, Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts, and Mind-wandering explain additional variance over and above d. Specifically, in

Panel B, d and the non-d residual of External Distraction served as predictors. In Panel C, d and the non-d residual of Unwanted

Intrusive Thoughts served as predictors. In Panel D, d and the non-d residual of Mind-wandering served as predictors. In all panels,

manifest variables were not shown. The directional paths were not meant to imply causation.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215.g004

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 18 / 31

The model shown in Fig 4D used the residual of Mind-wandering as an additional predictor.

The fit of the model was good, χ

2

(80) = 316.06, p < .001; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .07 [.06, .08];

SRMR = .040; BIC = 19,539. The results, summarized in Table 4, show that Mind-wandering

residual was not significantly associated with ADHD symptoms or functional impairments.

There was a positive relationship with hyperfocus, such that a higher susceptibility to mind-

wandering was associated with a stronger tendency to engage in hyperfocus even after control-

ling for d.

Overall, our analyses using Sample 1 show that d was the dominant predictor of ADHD

symptoms and functional impairments. When the residual factors were added, there were

some minor fluctuations in the effects of d, but d still remained a highly significant predictor.

In contrast, the residuals of External Distraction, Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts, and Mind-

wandering did not explain meaningful variance in ADHD symptoms and functional

impairments.

The results for hyperfocus were more complex. While d was also positively associated with

hyperfocus, the residuals of External Distraction and Mind-wandering also explained addi-

tional variance. Interestingly, when controlling for d, increased susceptibility to external dis-

traction was associated with a weaker tendency to engage in hyperfocus, whereas increased

susceptibility to mind-wandering was associated with a stronger tendency to engage in hyper-

focus. This contrasting pattern of results will be discussed in more depth later in the Discus-

sion section.

Replication with Sample 2. All the results for Sample 1 were replicated in the Sample 2

data (see Table 4). First, the model with d as the only predictor (Fig 4A) had a good fit, χ

2

(83)

= 258.75, p < .001; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .06 [.06, .07]; SRMR = .046; BIC = 16,639. A higher d

was associated with a higher level of ADHD symptomatology, greater functional impairments,

and a stronger hyperfocus tendency.

Second, the model with the residual of External Distraction as an additional predictor (Fig

4B) had a good fit, χ

2

(80) = 242.69, p < .001; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .06 [.05, .07]; SRMR = .042;

Table 4. Standardized path coefficients of the unity and diversity components of distractibility predicting ADHD symptoms, ADHD functional impairments, and

hyperfocus.

Models Sample 1 Sample 2

ADHD Symptoms Functional Impairments Hyperfocus ADHD Symptoms Functional Impairments Hyperfocus

Model A

d .78*** .66*** .36*** .74*** .67*** .37***

Model B

d .78*** .66*** .39*** .74*** .68*** .40***

External Distraction Residual -.01 -.03 -.19*** .01 -.06 -.16***

Model C

d .80*** .65*** .35*** .74*** .65*** .38***

Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts

Residual

-.07 .01 .04 -.02 .06 -.02

Model D

d .75*** .65*** .31*** .72*** .67*** .29***

Mind-wandering Residual .11 .04 .16* .08 .02 .22*

Note. The results of models A-D correspond to the models shown in Fig 4.

*p < .05,

***p < .001.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215.t004

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 19 / 31

BIC = 16,641. External Distraction residual was not significantly associated with ADHD symp-

toms and functional impairments, but it was negatively and significantly associated with

hyperfocus.

Third, the model with the residual of Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts as an additional predic-

tor (Fig 4C) had a good fit, χ

2

(80) = 255.23, p < .001; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .07 [.06, .07];

SRMR = .046; BIC = 16,654. Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts residual did not significantly

explain additional variance in any of the variables.

Finally, the model with the residual of Mind-wandering as an additional predictor (Fig 4D)

also had a good fit, χ

2

(80) = 252.46, p < .001; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .07 [.06, .07]; SRMR = .044;

BIC = 16,651. Mind-wandering residual was not significantly associated with ADHD symp-

toms and functional impairments, but it was positively and significantly associated with

hyperfocus.

Additional analyses. We also conducted two additional analyses, both of which can be

found in S2 File. First, the relationship between d and hyperfocus was relatively weaker com-

pared to ADHD symptoms and functional impairments (Supplemental Analysis 1 in S2 File).

Second, while d was substantially associated with both inattention symptoms (e.g., having diffi-

culty keeping attention) and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms (e.g., fidgeting or squirming

with hands or feet), it was more strongly associated with inattention symptoms (Supplemental

Analysis 2 in S2 File). None of the residual factors explained meaningful variance. Both analy-

ses were replicated in Sample 2.

Discussion

The current study aimed to understand the factor structure of distractibility. Using a latent

modeling approach, we assessed how individual differences in self-reported vulnerability to

several forms of real-world distraction were related. Based on the pattern of the correlations,

we developed a latent-variable model that incorporates a higher-order common factor to cap-

ture individual differences in general distractibility. We then examined how this higher-order

model can account for individual differences in ADHD behavioral symptoms, ADHD func-

tional impairments, and hyperfocus.

With two large samples, we conducted exploratory analyses using the first sample and an

internal replication using the second sample. It is worth noting that the characteristics of the

two samples were substantially different in terms of age (26.9 ± 5.0 in Sample 1 vs. 18.8 ± 1.2 in

Sample 2), gender distribution (45.3% female in Sample 1 vs. 66.3% female in Sample 2), racial

composition (67.7% white in Sample 1 vs. 56.8% white in Sample 2), and occupation (33.9%

college students vs. 100% college students). Despite these differences, all key results in Sample

1 were successfully replicated in Sample 2, thus providing solid empirical ground for the fol-

lowing discussion of results.

Goal 1: Understanding the relationships among different facets of

distractibility

Whereas the term “distraction” is commonly used to describe how our attention is diverted by

both internal (e.g., our own thoughts) and external (e.g., pop-up advertisements) sources in

daily life, the study of distraction has focused heavily on the latter. Although other fields have

studied phenomena such as mind-wandering and intrusive thoughts, there has been relatively

little integration between them until recently [55].

Extending previous findings, a critical finding of our study is the identification of a higher-

order factor that could be construed to represent a general distractibility trait. Indeed, we

found that there was very much in common among external distraction, unwanted intrusive

PLOS ONE

Distractibility, ADHD, and hyperfocus

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292215 October 25, 2023 20 / 31

thoughts, and mind-wandering: d accounted for about 80% of the total variance in the three

factors (83% in Sample 1 and 77% in Sample 2). A measurement invariance analysis further

showed generalizability of the higher-order model at the parameter level. Taken together, our

findings underscore the notable shared variance among several distractibility-related con-

structs, suggesting a reliable trait reflecting individual differences in (perceived) distractibility.

Goal 2: Linking distractibility to ADHD symptoms and hyperfocus

ADHD symptoms and associated functional impairments. In Goal 2 of the current

study, we related our higher-order model of distractibility to individual differences in self-

reported ADHD symptoms and functional impairments. Across two samples, we found that d

was substantially related to individual differences in ADHD symptoms and functional impair-

ments. Furthermore, d was more related to the inattentive symptoms than to the hyperactive/

impulsive symptoms (see Supplemental Analysis 2 in S2 File). These results further speak to

the validity of d as a measure of general distractibility.

These results also have important implications for the nature of the heightened distractibil-

ity in ADHD. Existing research on distractibility and ADHD has often examined specific facets

of distractibility in isolation and thereby neglected the substantial overlap among different fac-

ets of distractibility. When ADHD is simultaneously associated with vulnerability to multiple

forms of distraction, it may be more parsimonious to view these associations as reflecting a sin-

gle association with general distractibility rather than separate associations with each specific

form of distractibility. In fact, our results show that once d was included in the model, none of

the residual factors explained variance in ADHD symptoms above and beyond d. In particular,

External Distraction did not explain any meaningful variance in ADHD symptoms and func-

tional impairments beyond d despite its substantial construct-specific variance. Thus, the

results indicate that the heightened distractibility in ADHD symptomatology is best character-

ized by general distractibility instead of by any single type of distraction alone.

Hyperfocus. Our findings provide insight into the nature of hyperfocus. We discovered

that individuals who were more generally distractible tended to report more frequent hyperfo-

cus episodes. This counterintuitive relationship implies that focused and distracted attention

might share some underlying features. One possible interpretation is that individuals often

hyperfocus on the same subjects that distract them from more critical tasks. For example,

someone might hyperfocus on watching TV, which serves as a distraction from their work

assignments. Alternatively, distractibility and hyperfocus might both be indicative of deficits

in attentional control. Consequently, individuals who are easily distracted by irrelevant infor-