REPORT 633

Holes in the safety net:

A review of TPD

insurance claims

October 2019

About this report

This report summarises the findings and recommendations from ASIC’s

thematic review of total and permanent disability (TPD) insurance in

Australia.

In particular, it reviews outcomes for consumers, claims handling practices,

the role of data in managing the risk of consumer harm, and our findings on

insurers with higher than predicted rates of declined claims.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 2

About ASIC regulatory documents

In administering legislation ASIC issues the following types of regulatory

documents.

Consultation papers: seek feedback from stakeholders on matters ASIC

is considering, such as proposed relief or proposed regulatory guidance.

Regulatory guides: give guidance to regulated entities by:

explaining when and how ASIC will exercise specific powers under

legislation (primarily the Corporations Act)

explaining how ASIC interprets the law

describing the principles underlying ASIC’s approach

giving practical guidance (e.g. describing the steps of a process such

as applying for a licence or giving practical examples of how

regulated entities may decide to meet their obligations).

Information sheets: provide concise guidance on a specific process or

compliance issue or an overview of detailed guidance.

Reports: describe ASIC compliance or relief activity or the results of a

research project.

Disclaimer

This report does not constitute legal advice. We encourage you to seek your

own professional advice to find out how the Corporations Act and other

applicable laws apply to you, as it is your responsibility to determine your

obligations.

Examples in this report are purely for illustration; they are not exhaustive and

are not intended to impose or imply particular rules or requirements.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 3

Contents

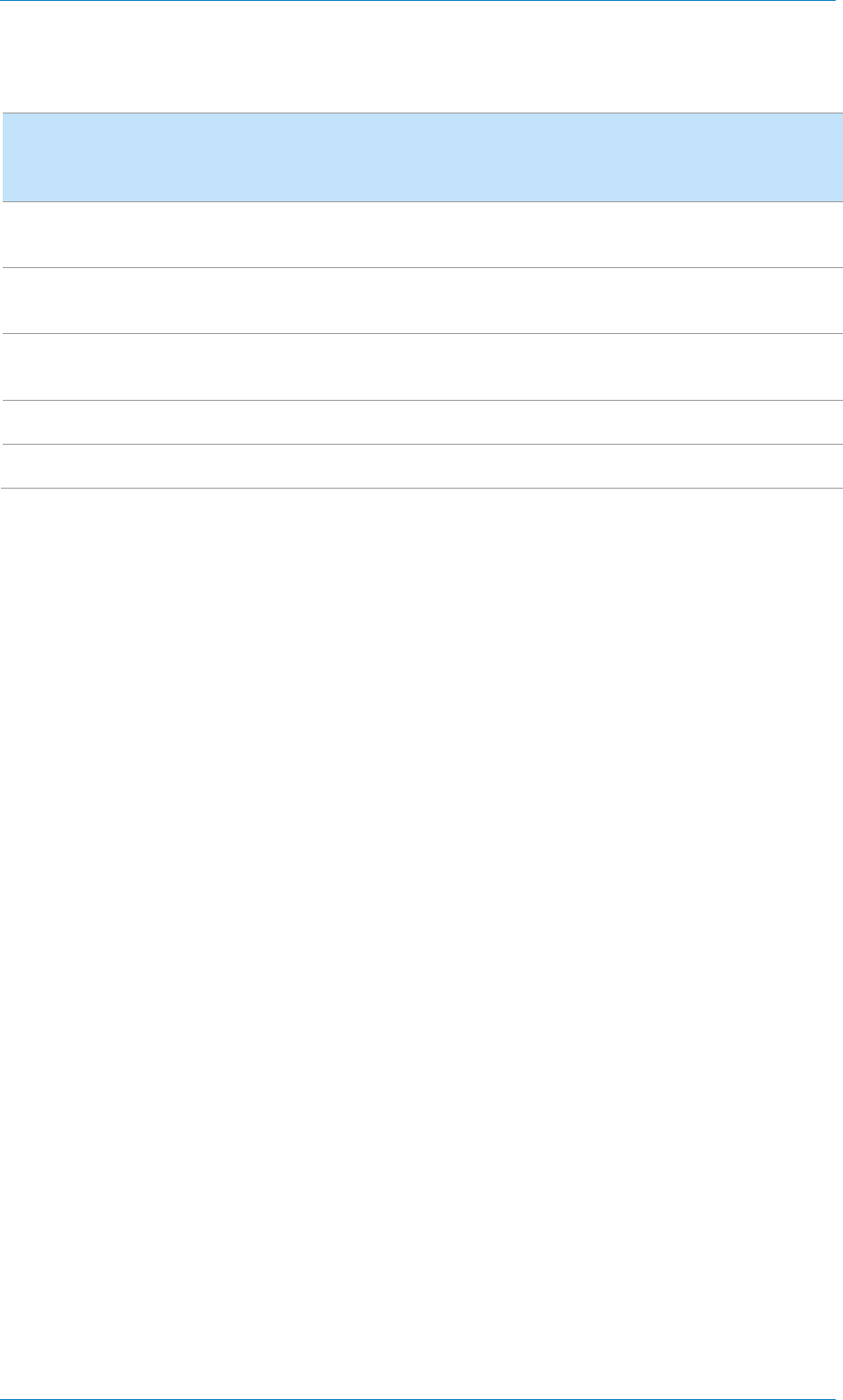

Executive summary ................................................................................. 4

What we did in this review ................................................................. 6

Summary of findings .......................................................................... 7

ASIC’s expectations and action ....................................................... 16

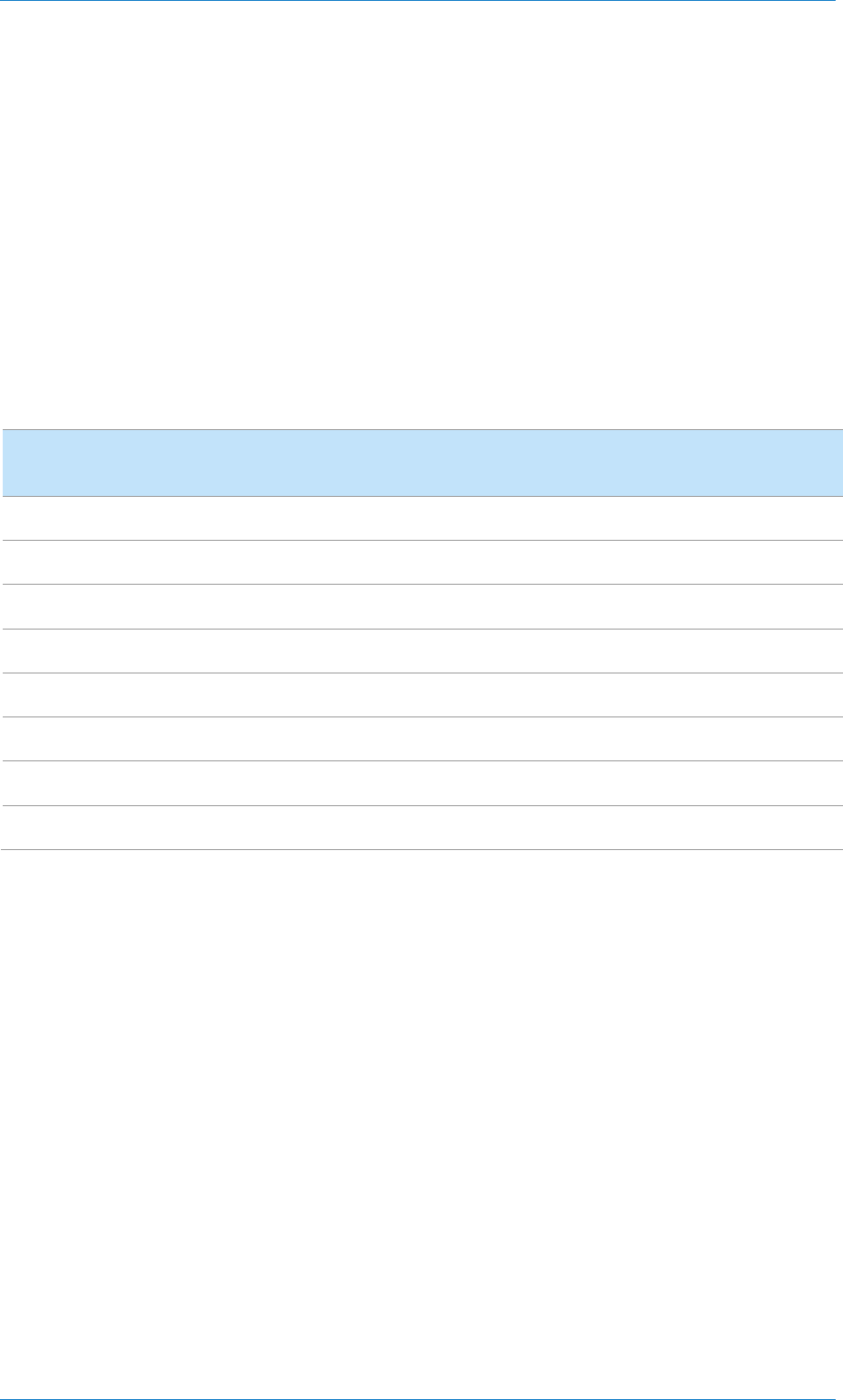

A TPD insurance in Australia ........................................................... 20

What is TPD insurance? .................................................................. 20

Snapshot of the TPD insurance market ........................................... 22

Regulatory environment and gaps ................................................... 24

B Poor consumer outcomes from the activities of daily living

(ADL) test ........................................................................................ 31

The significance of eligibility criteria in TPD cover .......................... 31

Detailed data findings on ADL claims .............................................. 36

Consumer harms from low-value ADL cover ................................... 43

Other TPD product design issues .................................................... 44

Further action ................................................................................... 47

C Claims handling and withdrawn claims ...................................... 50

Withdrawn claim rates ..................................................................... 50

Why claims are withdrawn ............................................................... 51

The claim lodgement process .......................................................... 53

Frictions in the claim assessment process ...................................... 57

Further action ................................................................................... 69

D Poor-quality data and consumer harm ........................................ 72

Good data is essential for managing the risk of consumer harm .... 73

Insurers had poor data ..................................................................... 75

Further action ................................................................................... 84

E Declined claims: Findings and outliers ....................................... 86

Industry-wide findings on key factors .............................................. 88

Findings on insurer-declined claim rates ......................................... 94

Further action ................................................................................... 96

Appendix 1: Methodology .................................................................... 97

Our approach ................................................................................... 97

Stakeholder consultation ................................................................. 98

Data collection ................................................................................. 98

Statistical analysis of declined claim data ....................................... 99

Qualitative review .......................................................................... 101

Consumer research ....................................................................... 102

Appendix 2: Accessible versions of figures ..................................... 103

Key terms ............................................................................................. 108

Related information ............................................................................. 113

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 4

Executive summary

1 Total and permanent disability (TPD) insurance is a type of life insurance that

pays a lump sum if the consumer becomes totally and permanently disabled

under the terms of the insurance policy. Its purpose is to replace future

retirement savings lost due to disablement. A TPD benefit can also help with

the costs of rehabilitation, debt repayments and future costs of living.

2 TPD insurance is widely held—over 13.4 million consumers have TPD cover

and almost 90% are insured through their superannuation fund. It plays a

crucial role as a safety net in supporting the financial security of Australians.

During the 12 months to 31 December 2018, TPD insurance premiums totalled

$3.548 billion and consumers made more than 26,000 claims.

3 This report builds on ASIC’s previous review of life insurance in Report 498

Life insurance claims: An industry review (REP 498). In REP 498 we

identified several concerns about TPD insurance including above-average

declined claim rates, high rates of withdrawn claims and poor claims-

processing times. We undertook to review TPD claims processes.

4 In REP 498 we found that only 65% of notified TPD claims were accepted

by insurers, with the balance of claims either declined by the insurer or

withdrawn by the consumer. We were concerned that the acceptance rate

indicates problems both with the design of TPD policies (with cover being

too restrictive under some policies) and with claims handling procedures.

5 This report identifies four important industry-wide issues that insurers and

superannuation trustees must fix: see Table 1. They are not the only

problems associated with TPD insurance. Other issues include the role of

rehabilitation providers and the difficulty of comparing TPD definitions

particularly in the context of insurance in superannuation (both of which are

touched on in this report).

6 However, we consider that these four issues in particular create poor consumer

outcomes and are connected to our undertaking in REP 498

to review TPD

claims processes. We expect insurers and superannuation trustees to address

the problems we have identified. ASIC will also take action to address these

issues. We have set out ASIC’s expectations and actions in

Table 3.

7 ASIC will take further action, including enforcement action where

appropriate, against insurers and superannuation trustees who fail to properly

address our concerns. We will also consider using our product intervention

powers to prevent harm to consumers.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 5

Table 1: Four key industry-wide issues in the TPD market

Issue

What we found

Poor consumer

outcomes from the

‘activities of daily

living’ test

Many insurers selling policies with restrictive cover based on the ‘activities of daily

living’ (ADL) disability test. These policies make some consumers eligible only for a

narrow form of TPD cover due to their work status (e.g. non-permanent, casual or

part-time employees). This narrow cover pays out only if consumers cannot perform

several ‘activities of daily living’ such as feeding, dressing or washing themselves.

We consider that these policies are not designed for, and do not operate to meet the

needs of, the broad range of consumers who are funnelled into this type of cover.

These policies do not appear to provide cover for all consumers who are unable to

work again—they provide cover only to consumers who are so severely disabled that

they cannot care for themselves.

Frictions in claims

handling leading to

withdrawn claims

Approximately 12.5% of TPD claims during the period of our review were withdrawn.

We consider that this high withdrawal rate is, at least, partially due to insurers

subjecting consumers who are vulnerable (due to life-altering illness or injury) to a

claims process that is often unnecessarily challenging and onerous.

Consumer harm

arising from poor data

Insurers had significant deficiencies in their ability to record and search for relevant

claims data. Without accurate and timely data, insurers cannot identify problems in

their products or processes, or determine the changes needed to address problems

and improve consumer outcomes. Insurers will need better data to help them meet

the design and distribution obligations, which will take effect from April 2021.

Insurers with higher

than predicted

declined claim rates

Claims with certain characteristics such as the type of underlying condition or

occupation of the consumer had higher than predicted declined rates. Our analysis

also found that three insurers had higher than predicted declined claim rates: see

paragraphs 41–46.

Key role of superannuation trustees

Insurance is an important feature of the superannuation system and most

superannuation funds offer their members life insurance cover in addition to

retirement benefits. Trustees of MySuper products are generally required by

law to offer members death cover and TPD cover on an opt-out basis.

MySuper products are designed for a broad range of consumers including

those who are highly disengaged.

While our review was focused on insurers, superannuation trustees play a

crucial role in the delivery of life insurance to superannuation fund members,

as they must approve the design of the policy, choose an insurer and agree

commercial terms, and act as the policy holder for group insurance.

We expect superannuation trustees to act in their members’ best interests by

providing access to affordable insurance products that are suitably designed

for their members. This includes safeguarding their members’

superannuation balances from inappropriate erosion.

We also expect superannuation trustees to play a robust role alongside

insurers in ensuring a good claims experience for consumers. This role

encompasses not just advocating for claims with reasonable prospects of

success, but also actively engaging with the consumer’s claim journey to

make sure processes are simple, timely and transparent. This includes the

management of any insurance-related complaints.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 6

What we did in this review

8 Figure 1 summarises the different elements of our review. For further details

of our methodology, see Appendix 1 of this report. The review covered the

period from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2017.

Figure 1: What we did

Note: See Appendix 1 of this report for an accessible version of the information contained in Figure 1. For details of the

methodology and limitations of our consumer research, see paragraphs 358–365 in Appendix 1.

9 The following insurers were included in our review:

(a) AIA Australia Limited (AIA);

(b) AMP Life Limited (AMP) and The National Mutual Life Association of

Australasia Limited—part of the AMP Group of companies;

(c) Asteron Life & Superannuation Limited (Asteron)—previously known

as Suncorp Life & Superannuation Limited (Suncorp);

(d) MetLife Insurance Limited (MetLife);

(e) MLC Limited (MLC);

(f) TAL Life Limited (TAL); and

(g) Westpac Life Insurance Services Limited (Westpac).

Note: On 28 February 2019, the Suncorp Group announced the completion of the sale of

its life insurance business to Japanese insurer Dai-ichi Life Holdings, which also owns

TAL. See Suncorp Group, Completion of Australian life business sale (PDF 22 KB),

ASX announcement, 28 February 2019.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 7

Summary of findings

Poor consumer outcomes from the ‘activities of daily

living’ test

Finding 1: Claims assessed under the ‘activities of daily living’ test

generally result in poor outcomes, with three out of five such claims

being declined

10 TPD cover is designed for people who are totally and permanently disabled.

However, the meaning of total and permanent disablement varies between

the different TPD products distributed by insurers.

11 Most consumers who make a claim are assessed under the so-called ‘any

occupation’ or ‘own occupation’ tests. Under these tests, consumers making

a claim are considered totally and permanently disabled if they are unable to

work in ‘any occupation’ or their ‘own occupation’ again. However, some

consumers may be paying premiums for TPD cover under a more restrictive

policy definition—the ‘activities of daily living’ (ADL) test.

12 We found that the declined rate for TPD claims assessed under the ADL test

was very high: 60%, or three in five claims, were declined. This was five

times higher than the average declined rate for all other TPD claims (12%).

13 Although ADL claims represented a relatively small percentage of all TPD

claims in our review (4%), based on the 26,150 TPD claims made across all

life insurers in 2018 this translates to almost three claims per day being

assessed under this restrictive definition.

14 The declined rates for TPD claims assessed under the ADL test were

concerningly high for some group superannuation policies. The 10 highest

ADL declined rates at group policy level ranged from 45% to 87%: see

paragraphs 114–118 and Table 6 in this report.

15 There is the risk of harm when consumers pay for ADL cover in that:

(a) they are paying premiums for insurance cover that they are unlikely to

be able to successfully claim on and therefore cannot rely on if they are

disabled;

(b) because most consumers have automatic insurance through their

superannuation, they generally pay the same premium regardless of

whether, in the event of a claim, they are eligible for ADL-only cover or

more general TPD cover; and

(c) economically vulnerable consumers are especially disadvantaged as the

eligibility criteria often mean that casual, contract or seasonal

employees are funnelled into ADL-only cover.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 8

Finding 2: Eligibility criteria in group insurance cover mean that some

consumers are automatically funnelled into low-value ADL cover

which may not be worth paying for

16 Consumers who do not meet certain eligibility criteria in group cover are

often assessed under the restrictive ADL definition.

17 The eligibility criteria in group TPD cover mean that the following

consumers are typically funnelled into the narrower ADL definition:

(a) casual, seasonal or part-time employees who work less than a specified

number of hours (e.g. 15 hours per week);

(b) people who have been unemployed or on leave without pay for a stated

period before the TPD event (often six months, but for some policies

12 months); and/or

(c) people in specified occupations that the insurer considers are high risk.

18 ASIC is concerned that these types of eligibility criteria unfairly affect more

vulnerable consumers, including unskilled workers, people with parental or

other caring responsibilities, and workers in certain industries such as retail

and hospitality. With the changing nature of the workforce and the growth of

the ‘gig economy’, these types of eligibility criteria will capture an

increasingly broad range of consumers.

19 The risks to consumers who hold these types of group policies are

heightened by the low level of engagement that most consumers have with

insurance in superannuation. As the Productivity Commission noted in its

recent report on superannuation, 24% of superannuation members surveyed

did not know whether there was insurance in their fund, and a further 16%

knew they paid for insurance but did not know what they were covered for.

These consumers are likely to be unaware that their insurance may provide

less cover if their employment changes. Consumers are relying on unusable

cover when they could potentially purchase more suitable cover.

Note: See Productivity Commission, Superannuation: Assessing efficiency and

competitiveness, inquiry report no. 91, December 2018 (Productivity Commission

report), pp. 384–5.

20 The fact that 4% of TPD claims are assessed under the ADL test means that

at least 4% of the 12 million consumers (480,000) who hold TPD in

superannuation are potentially at risk of unusable or inadequate cover.

21 The complexity of and lack of comparability across insurance offerings also

make it difficult for consumers to compare policies and understand the cover

they have. Our findings endorse the need for greater standardisation of

terms, especially within superannuation.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 9

Finding 3: The ADL test is unsuitable for a range of common illnesses

and injuries, including mental illness and musculoskeletal disorders

22 The ADL test is suited only to disability caused by the most catastrophic

type of injury or illness. When we compared declined claim rates for certain

conditions under the narrower ADL definition with rates under the broader

general TPD definition, we found that:

(a) mental health claims were approximately five times more likely to be

declined (77% for ADL compared to 15% for the general definition);

and

(b) musculoskeletal claims were more than five times more likely to be

declined (71% for ADL compared to 13% for the general definition).

23 The concerningly high declined claim rate for consumers with mental illness

or musculoskeletal disorders assessed under ADL indicates that this type of

restrictive TPD cover is unsuitable for many consumers to whom it is being

provided or sold. These medical conditions may be a common cause of

disability for certain classes of employees (e.g. manual workers who may be

more susceptible to musculoskeletal injuries yet whose employment

arrangements mean they are defaulted into ADL-only TPD cover).

24 We are aware that one insurer has removed ADL cover from some TPD

policies offered within superannuation. This is a step in the right direction.

25 Superannuation trustees have a key role to play: they have a legal obligation

to offer insurance benefits for fund members (consumers) that are both

appropriate and affordable. Considering the needs of different consumer

cohorts may require careful balancing by trustees, and some degree of cross-

subsidisation is inherent in group insurance as it involves pooling risk.

However, we expect insurers and trustees to stop providing ‘junk’ insurance

products to consumers. Trustees and insurers must ensure that the products

they design and/or distribute are suitable for the consumers to whom they are

provided or sold.

Frictions in claims handling leading to withdrawn claims

Finding 4: Insurers do not have sufficient understanding of the

reasons for withdrawn claims

26 Withdrawn claims are an important indicator of potential consumer harm.

Consumers suffer harm if claims handling processes contain frictions which

result in consumers withdrawing potentially valid claims. The way in which

a claim is withdrawn, and the timing of the withdrawal, may indicate where

there are frictions in the claims handling process. Withdrawn claim rates

may also mask real declined claim rates.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 10

27 Insurers were generally poor at capturing reasons for withdrawn claims. We

found that for over 50% of withdrawn claims, the reason given by the insurer

was lack of response by the consumer to a request for information. This lack

of response could be driven by factors which, if identified, could be properly

addressed.

28 The second most common reason recorded was the consumer withdrawing

for reasons other than eligibility or return to work (31%). Insurers did not

record the actual reason for these active withdrawals.

29 While we acknowledge that it is not always possible for an insurer (or

superannuation trustee) to know the reasons for withdrawn claims, we expect

insurers to improve their understanding of these reasons. When a consumer

begins a claim via a trustee for insurance held in superannuation, a

superannuation trustee has obligations to pursue insurance claims for

members. Therefore, we expect trustees to improve their own understanding

of the reasons for withdrawn claims.

Finding 5: Insurers’ claims handling practices create frictions that

contribute to consumers withdrawing claims

30 Our consumer research found that consumers had limited time, ability, focus

and/or funds to manage a TPD claim because they:

(a) were typically impaired or in pain due to a life-altering illness or injury;

(b) were often dealing with numerous other issues connected with their

illness or injury—medical appointments, overdue bills and debt

collectors, or separate legal processes (e.g. WorkCover, claims against

their employer, and public liability insurance claims); and

(c) had limited or no income to live on.

31 Information obtained from insurers together with our consumer research

identified numerous frictions for consumers in the claim assessment process,

including the following:

(a) Poor insurer communication practices—The way in which insurers’

claims staff communicated with consumers had a significant effect on

consumer experience; empathetic and proactive communication is key

to good claims-handling practice.

(b) Multiple requests for further medical assessments—These requests

often seemed unreasonable or unnecessary and were a concern

reiterated throughout our consumer research.

(c) Potentially threatening behaviour, including surveillance of claimants

and questionable allegations of fraud—Seven out of 20 consumers we

interviewed in our consumer research were subject to physical

surveillance and reported experiencing additional stress. This was not

drawn from a representative sample of claims (details of the

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 11

methodology used are contained in Appendix 1 of this report). Yet our

data analysis showed that where physical surveillance was used more

broadly, the insurer ultimately admitted the claim in over 60% of cases.

(d) Excessive delay—Delay in receiving a claims decision was an issue for

many of the consumers who participated in our consumer research.

‘Unexpected circumstances’ allow insurers to extend the promised

timeframe in the Life Insurance Code of Practice (Life Code) for a TPD

claims decision from six months to 12 months.

(e) ‘Fishing’ for non-disclosure—The Royal Commission into Misconduct

in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry (Royal

Commission) raised concerns about insurers seeking to avoid claims by

relying on a legal technicality rather than supporting the consumer

through the claims process.

(f) Ongoing costs of the claims process—The claim assessment process,

including being asked to attend multiple medical appointments, can be

‘time consuming, costly and painful’.

(g) Changes to claims staff—Several consumers emphasised the difficulties

they encountered when the staff managing their claim changed. We

found that several insurers in our review had a claims staff turnover rate

near or above 25% for one of the two years of our review.

32 Our consumer research and data analysis showed that these practices and the

frictions they created contributed to the withdrawal of 4,365 claims during

the period of our review—approximately one out of eight claims reported.

Consumer harm arising from poor data

Finding 6: Insurers did not have adequate data to effectively manage

the risk of consumer harm

33 Good data is key for the effective and proactive management of the risk of

consumer harm. To effectively manage consumer harm, insurers need data

that is timely, accurate, adequate and complete and that uses consistent

definitions. Without timely and insightful data, insurers cannot proactively

identify and address, in a targeted manner:

(a) the value of products to consumers and whether the products are

meeting consumer needs;

(b) key friction points in the TPD claims handling process;

(c) claims handling staff whose conduct may give rise to a higher

likelihood of consumer harm;

(d) claims handling practices leading to consumer harm; and

(e) harm caused to consumers at either a granular or consolidated level.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 12

34 Our review found that, to varying degrees, all seven insurers failed to meet

our criteria for ‘good data’ during 2016 and 2017, for the reasons set out in

Table 2.

Table 2: Findings on insurers’ data resources

Insurers’ responses to our data

requests were slow

No insurer could provide a complete response to our data request by the

due date (a reasonable time in which to respond). Full responses from

some insurers were still outstanding five months after we requested

claims data under statutory notice.

Crucial data was not readily

available in searchable formats

All insurers needed to conduct manual reviews to extract relevant data,

including reviewing paper files.

Some requested data was not

available at all

Some insurers could not tell us how many claims they had assessed

under an ADL definition. Most insurers could not provide accurate data

on something as fundamental as whether a consumer had withdrawn a

claim because they had returned to work.

All insurers’ responses contained

errors

Some insurers resubmitted errors to ASIC after we had informed them of

the errors in our initial feedback.

There were no standard

definitions for key data

This lack of consistency was particularly problematic for claims

notification and lodgement. For example, insurers used a range of

practices to record when a claim ‘begins’. This issue has been improved

through work undertaken with the Australian Prudential Regulation

Authority (APRA)—the ASIC-APRA life claims data collection work.

Insurers did not have access to

comprehensive data about

insurance in superannuation

claims

For some insurance in superannuation claims, insurers became involved

in a claim after the superannuation trustee passed details of a claim and

the consumer on to them. Insurers usually did not have information about

what occurred before the claim was passed on to them—including the

amount of time since the consumer first notified the trustee of the claim,

which is fundamental to understanding how a consumer has been

pursuing a claim.

35 No insurer had a holistic, up-to-date picture of the potential consumer harm

arising from TPD claims handling and outcomes. They could only get this

information from reactive, post-event quality assurance reviews, audits or

analysis—by which time conduct risk and consumer harm had already

crystallised.

Finding 7: Despite some improvements, insurers must invest more

time, resources and funds to strengthen data resources to effectively

reduce the risk of consumer harm

36 Insurers are already improving their data capability largely to meet the

requirements of APRA and ASIC’s data collection initiatives. However,

insurers must do more to address the issues we have identified. We expect

boards and owners of all insurers to ensure there is sufficient investment in

the business to appropriately manage the risk posed by inadequate data

resources. This will require additional investment and the active engagement

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 13

of boards and senior management. We also expect superannuation trustees to

ensure that they receive adequate data from insurers to manage the risk of

harm to their members (consumers).

37 Recent and anticipated changes to life insurer ownership create an

opportunity for these issues to be resolved. We are aware of at least one new

owner investing in data and systems since buying a life company from an

Australian bank, and we encourage other owners to do the same.

Insurers with higher than predicted declined claim rates

Finding 8: Different factors, such as the TPD definition, the consumer’s

age and the underlying TPD condition, have significantly different

likelihoods of a claim being declined—unfairly affecting some consumers

38 We analysed the data we collected and used statistical modelling to identify

factors that were statistically significant in relation to the likelihood of a

claim being declined. Based on the results, ASIC is concerned that

consumers with these characteristics may be receiving unfair treatment.

39 In addition to the significant variations between claims assessed under different

TPD definitions, we made the following findings across the seven insurers:

(a) There was a significant difference between the declined rates for

disease-related claims and for claims for other conditions. Mental

illness–related claims had the highest declined rate at 16.9% closely

followed by injury or fracture conditions at 16.1%. TPD claims for

disease-related conditions had a lower declined rate of 9.7%. While

there may be legitimate reasons for this difference, we expect insurers

to ensure that their claims handling procedures are not operating

unfairly for consumers with mental health, injury or fracture conditions.

(b) The rate of declined claims decreased as the age of the consumer

increased. This could be expected, as it is more difficult for an insurer

to determine that a younger person will never be able to work again,

than to determine the same for an older person. However, two

insurers—MLC and TAL—had a noticeably lower rate of declined

claims for younger consumers. We will be working with the other

insurers to understand this difference.

(c) The age of the policy at the claim event date (the number of days since

the policy began, to the date of the TPD claim) is significant. Generally,

the longer a policy is in force, the lower the declined claim rate.

(d) The length of any delay in claim reporting is significant. Claims that

were reported more than 1,000 days after the claim event were declined

at a higher rate—around 17.4% compared to 12.4% for other claims.

We will be working with insurers, particularly where the insurer on risk

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 14

for a claim is no longer the current insurer for the relevant

superannuation fund, to understand this difference.

(e) There was only a slight difference between the declined rates for claims

on group policies (13.6%) and for retail policies (14.5%).

40 We expect all insurers to review their claims handling practices in light of

this analysis to ensure they are not treating groups of consumers unfairly.

Finding 9: TPD declined claim rates varied significantly between

individual insurers

41 As Figure 2 shows, TPD declined claim rates varied significantly among

insurers, from TAL with a declined rate of 9% to Westpac and Asteron with

declined rates of 28% and 29% respectively.

Figure 2: Declined claim rates for TPD cover, by insurer (2016–17)

Source: ASIC data collection

Note 1: Some of the difference in declined claim rates between insurers can be explained by the

relative mix of each insurer’s policy portfolio and distribution channel including:

• distribution channels: the declined claim rates vary for group (13.6%), retail (14.5%) and

direct (22.6%) (see Table 20 in this report); and

• policies open for sale and closed to sale (i.e. legacy products).

Note 2: See Table 24 in Appendix 2 of this report for the underlying data (accessible version).

42 We collected data about more than 35,000 TPD claims to improve our

understanding of these declined rates. The granularity of our data collection

allowed us to conduct industry-wide analysis that, to our knowledge, has not

been undertaken in the Australian life insurance market before. By assessing

the individual characteristics of each claim, we were able to predict the

declined claim rate for each insurer based on the features of its claims and

then identify factors that contributed to any variance from the predicted rate.

29%

28%

18%

16%

15%

12%

9%

71%

72%

82%

84%

85%

88%

91%

Asteron

Westpac

MLC

AIA

AMP

MetLife

TAL

Declined claims Accepted claims

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 15

43 The data we collected allowed us to analyse the following 10 factors:

(a) the type of definition the claims were assessed under (i.e. ADL, ‘any

occupation’ and ‘own occupation’);

(b) the age of the consumer making the claim;

(c) the primary medical condition giving rise to the claim;

(d) whether the claim was formally underwritten and tailored in some way

to the consumer;

(e) the type of policy the claim was made on (i.e. a group policy, a retail

policy or a direct policy);

(f) the gender of the consumer making the claim;

(g) the amount the consumer was insured for under the policy;

(h) the delay between the date the claim was made and the date that the

consumer became aware of the primary condition;

(i) the length of time the policy had been in effect; and

(j) whether the consumer had a white-collar or blue-collar occupation.

44 The methodology, analysis and statistical results were reviewed and

confirmed as appropriate by Finity Consulting, an actuarial consultancy firm.

The limitations of our methodology, analysis and conclusions are set out in

Appendix 1 of this report.

Finding 10: AMP, Asteron and Westpac had higher than predicted

declined rates for claims with certain characteristics

45 As illustrated by Figure 3, our analysis showed that for claims where a

decision had been made, AMP, Asteron and Westpac had declined claim

rates higher than our analysis predicted. The declined claim rate for Asteron

was almost double what our analysis predicted.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 16

Figure 3: Actual declined rates compared to ASIC-predicted declined rates for claims that

went to a final decision, by insurer (2016–17)

Source: ASIC data collection

Note: See Table 25 in Appendix 2 of this report for the underlying data shown in this figure (accessible version).

46 We may undertake targeted surveillance work to examine the reasons for the

substantially higher declined claim rates and consider appropriate regulatory

action if required.

ASIC’s expectations and action

47 Table 3 summarises our expectations of insurers and superannuation trustees

based on the findings of our review, along with the action we will be taking.

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

Asteron Westpac

AMP

AIA Metlife TAL

MLC

Declined claim rate

Actual Predicted

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 17

Table 3: ASIC’s expectations

Problem

What we expect of insurers and superannuation trustees

What ASIC will do

Poor consumer

outcomes from

the ADL test and

other restrictive

definitions

(see Section B)

We expect all insurers and superannuation trustees (not just those

included in this review) to:

review all TPD policies that include ADL or other restrictive definitions

(e.g. ‘loss of limbs’) to:

− consider removing definitions in group policies that are so restrictive

as to make the policy unlikely to benefit the consumers to whom the

policy is sold or provided, or appropriately redesign the product; and

− develop measures to assess the value of the product offered or

provided to consumers;

improve data collection on outcomes for different types of TPD cover,

including ADL or other restrictive definitions; and

improve communications with consumers about the type of TPD cover

they will be eligible for under various circumstances.

We expect trustees to consider our findings when negotiating future

group insurance arrangements with insurers. Trustees must be confident

that the definition used for TPD in group insurance arrangements is

consistent with their duty to act in the best interests of fund members

(consumers).

We expect insurers to have addressed our expectations by 31 March

2020.

ASIC will conduct further work during 2020 and 2021 to assess the

suitability of ADL and other restrictive definitions in TPD policies and the

benefit to consumers of the policies that contain these definitions. This

work will be informed by additional data about restrictive definitions that we

expect industry to collect, particularly about claim outcomes, underlying

claim conditions and loss ratios for products where the ADL definition is

used.

ASIC will ask certain insurers selected at our discretion to report to us on

the changes made to their retail and direct product offerings, using our

compulsory notice powers under financial services laws if necessary. We

will consider reporting publicly on the appropriateness of the changes made

by insurers during 2020 and 2021.

We will also consider information that insurers report to us about their

analysis of each policy containing an ADL definition, the changes made to

the TPD policy (removal or redesign of the definition, including eligibility)

and the specific measures in place to assess consumer value. We will

consider using our product intervention powers to regulate the sale of

policies where we are satisfied that there is a reasonable likelihood of

consumer harm or detriment.

We will conduct targeted surveillance of insurers, particularly for products

that had the highest rate of declined claims for various definition types. We

will take enforcement action if appropriate.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 18

Problem

What we expect of insurers and superannuation trustees

What ASIC will do

Frictions in

claims handling

leading to

withdrawn

claims

(see Section C)

We expect all insurers and superannuation trustees to work constructively

towards a consistent set of binding standards for life insurance that

covers both insurers and trustees and contains robust standards for all

third-party providers. The next iteration of the Life Code and the

Insurance in Superannuation Code should incorporate additional or

enhanced obligations including for proactive communication with

consumers during their claim, appropriate use of desktop surveillance,

and documented guidelines on training and competency requirements for

claims handling staff.

We expect insurers and, where relevant, trustees to take immediate steps

to implement our recommended changes to claims handling practices,

reinsurer arrangements and claims staff remuneration scorecards.

We expect insurers to have addressed our expectations by 31 March

2020.

ASIC will consider changes to claims handling practices made by insurers

and superannuation trustees in response to this review and monitor

consumer outcomes including withdrawn claim rates. If we remain

concerned about claims handling practices and withdrawn claims, we will

use our current and proposed powers, including under the Corporations Act

2001 (Corporations Act), to intervene.

We will ask certain insurers selected at our discretion to report to us on the

changes made to their claims handling practices, using our compulsory

notice powers under financial services laws if necessary. We will consider

reporting publicly on the appropriateness of the changes made by insurers

during 2020 and 2021.

We have previously highlighted publicly the need for trustees to improve

their processes around claims handling. This report provides more insight

into areas for improvement and we expect trustees to review their

processes with the benefit of this report by 31 March 2020. We will be

engaging with trustees to review what progress has been made.

Consumer harm

arising from

poor data

(see Section D)

We expect all insurers to:

invest in data resources and improve the quality of their data;

develop plans and timeframes for further developing their data

capabilities to capture, store and retrieve data and information that is

necessary to adequately manage conduct risk and consumer harm;

collect more data including on withdrawn claims, product value,

consumer satisfaction, claim assessment practices, and involvement of

third parties such as legal representatives;

collect data that enables analysis of each individual policy offered

(including where there are multiple covers in one policy), not merely

data aggregated at an insurer level; and

continue to work with APRA and ASIC on the industry-wide collection of

life insurance claims data.

ASIC will recommend to Government strengthening the regulatory

framework for data resources and the management of conduct risk. Our

ability to intervene on issues of data resources and conduct risk

management is limited by the exemptions in s912A(4) and 912A(5) of the

Corporations Act. We recommend that these exemptions be removed.

We will work with APRA, insurers and stakeholders to improve insurers’

data resources. This will include using the types of data fields identified in

Table 14 in this report as the basis for confirming the data capabilities that

insurers need to have in order to capture, store and retrieve data and

information that is necessary to adequately manage conduct risk and

consumer harm.

We will continue to work with APRA to improve the public reporting regime for

claims data and outcomes including considering expanding its existing scope

beyond claims into underwriting and other non-claims areas.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 19

Problem

What we expect of insurers and superannuation trustees

What ASIC will do

Insurers with

higher than

predicted

declined claim

rates

(see Section E)

We expect all insurers to review their claims handling practices in light of

our analysis to ensure they are not treating certain groups of consumers

unfairly. They should also review a statistically significant sample of

declined claims between 1 January 2016 and 31 December with the

claims characteristics set out in Table 23 in this report.

Insurers should complete these reviews by no later than 31 March 2020.

ASIC may ask certain insurers selected at our discretion to report to us on the

outcomes of their reviews, using our compulsory notice powers if necessary.

We may also examine any steps taken by insurers to address the findings of

their reviews. We will consider reporting publicly on insurers’ response to

these expectations.

We may undertake targeted surveillance work to examine the reasons for

substantially higher declined claims rates.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 20

A TPD insurance in Australia

Key points

The growing and main channel by which TPD insurance is distributed is

through group policies; almost 90% of consumers with TPD cover are

insured through their superannuation fund.

Since the publication of REP 498 in 2016, ASIC has undertaken a range of

targeted surveillances and industry reviews to diagnose the drivers of poor

consumer outcomes in the life insurance market.

Important law reforms (such as the product intervention power and design

and distribution obligations) provide ASIC with a more flexible regulatory

toolkit. However, there are still regulatory gaps that restrict ASIC’s ability to

address consumer harm, particularly in the areas of claims handling, unfair

contract terms, licensee resource adequacy, and conduct risk

management. Additional reforms will allow us to address these gaps.

What is TPD insurance?

48 Total and permanent disability (TPD) insurance is a type of life insurance

that pays a lump sum if the consumer becomes totally and permanently

disabled under the terms of the insurance policy. Historically, a TPD

insurance benefit was intended to replace future retirement savings lost by

the consumer when they became disabled. A TPD benefit can also help with

costs of rehabilitation, debt repayments and future costs of living.

49 TPD cover is distributed in three main ways:

(a) group cover—purchased by the trustee of a superannuation fund or an

employer, for the benefit of fund members or employees;

(b) advised or retail cover—distributed through financial advisers; and

(c) non-advised or direct cover—distributed directly by insurers or their

partners or affiliates.

50 TPD policies define ‘totally and permanently disabled’ in different ways. In

2011 the NSW Court of Appeal described the general or ‘common form’ of

TPD definition as:

illness or injury which causes the life insured to be incapacitated to such an

extent as to render the member unlikely ever to engage in or work for

reward in any occupation or work for which he or she is reasonably

qualified by education, training or experience.

Note: See Manglicmot v Commonwealth Bank Officers Superannuation Corporation

Pty Ltd [2011] NSWCA 204

.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 21

Key TPD policy definitions

There are three main definitions of ‘totally and permanently disabled’ used

in TPD policies:

• Own occupation—The consumer is considered totally and permanently

disabled if they are unable to work in their ‘own occupation’ ever again.

Since 2014 this type of cover cannot be held within superannuation,

although some funds offer it as additional cover held outside

superannuation. It is typically more expensive cover.

• Any occupation—This is the general or ‘common form’ of TPD definition.

The consumer is considered totally and permanently disabled if they are

unable to work ever again in ‘any occupation’ for which they are suited

by ‘education, training or experience’. Increasingly, insurers are adding

‘rehabilitation’ or ‘retraining’ to this definition, making it harder to meet.

• ADL—The consumer is considered totally and permanently disabled if

they are unable to meet, usually, three ‘activities of daily living’ such as

feeding, bathing and toileting themselves.

Other types of TPD cover include ‘home duties’ and ‘loss of limbs’. The many

variations on these definitions make it hard for consumers to compare policies.

51 TPD is a complex and challenging product from a consumer perspective.

Sometimes it is difficult for an insurer to reach the conclusion that a person

meets the TPD definition (typically that they are unlikely ever to work

again). Insurers have at times taken a very cautious approach to paying

claims, although they are required to meet their obligations under the policy.

Superannuation is the main way life insurance cover is

provided in Australia

52 The introduction of the Superannuation Guarantee in July 1992 meant that

superannuation coverage expanded considerably—and with it the growth of

life insurance cover within superannuation.

53 Offering insurance cover through superannuation can provide consumers

with default access to beneficial cover at a competitive price, regardless of

their medical history. Superannuation trustees negotiate default coverage

with insurers for a set period (usually three years). Superannuation fund

members (the ultimate consumers) have coverage as specified in the policy

during that period. Trustees may re-tender insurance arrangements and

insurance arrangements may be renegotiated between trustee and insurer,

resulting in changes over time to the level or pricing of default cover, as well

as other aspects of the policy, such as automatic acceptance limits.

54 It is important to note that members only have access to the insurance

coverage in the policy that applied at the time they suffered the injury or

illness leading to the claim. In some cases, the TPD injury or illness could

occur several years before a claim is actually lodged. This means that some

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 22

insurers are liable to cover losses incurred by members of superannuation

funds that they are no longer insuring and no longer collecting premiums for.

55 In 2005 the Super Choice law reforms led to competition between insurers to

acquire and retain group life contracts with superannuation trustees. This

resulted in:

(a) pricing that did not always align with policy benefits—for example, an

increase in default coverage with no corresponding increase in

underlying premium rates, and in many cases a fall in rates;

(b) policies with generous ‘opt in’ features that allowed consumers to take

or increase cover with little or no evidence of health status; and

(c) in some cases—immediate rights to benefit, with ‘at work’ periods of as

little as one day to be eligible to make a claim.

56 These factors contributed to the increased value of TPD insurance through

superannuation. However, the pricing of that insurance was not sustainable

in the long term and has been followed by a tightening of policy terms and

an increase in premiums over the past five years.

Snapshot of the TPD insurance market

57 The TPD insurance market:

(a) is increasingly foreign owned—a series of acquisitions since 2016 has

seen the Australian life insurance industry become majority foreign

owned. Three of the four major banks have decided to sell their life

insurance businesses;

(b) is increasingly group policy focused—data published by APRA for the

2018 calendar year shows that almost 90% of consumers with TPD

cover obtained insurance through their superannuation fund;

Note: See APRA, Life insurance claims and disputes statistics (PDF 623 KB),

December 2018 (released 27 June 2019).

(c) continues to experience a high volume of claims—during the 12 months

to 31 December 2018, a total of 26,150 claims were made on TPD

cover (across all life insurers in the industry); and

(d) continues to experience low profitability—in the 12 months to

December 2018, life insurer net profit from all lump sum risk products

(a subset of which is TPD insurance) fell from $1.4 billion to $509

million, a reduction of more than 64%. This followed significant losses

experienced in the 2013 and 2014 financial years on group life

insurance.

Note: See APRA, Quarterly life insurance performance statistics, 28 February 2019.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 23

58 The most recent life insurance data published by APRA shows that total

annual life insurance premiums to 31 December 2018 were $17.351 billion;

of this amount, $3.548 billion was for TPD cover: see Figure 4.

Figure 4: Total life insurance premiums (millions of dollars), by cover type (at 31 December 2018)

Source: APRA, Life insurance claims and disputes statistics, December 2018 (released 27 June 2019)

Note: See Table 26 in Appendix 2 for the underlying data shown in this figure (accessible version).

59 As at 31 December 2018, there were 16 million lives insured for death cover,

and a comparable number (13.4 million) of consumers who had TPD cover.

For the actual number of lives insured by channel during the period, see

Figure 5.

Figure 5: Total lives insured (in thousands), TPD and death cover (at 31 December 2018)

Source: APRA, Life insurance claims and disputes statistics, December 2018 (released 27 June 2019)

Note: See Table 27 in Appendix 2 for the underlying data shown in this figure (accessible version).

6,390

5,033

3,548

1,469

478

322

111

Death cover

Income protection

TPD cover

Trauma cover

Funeral cover

Consumer credit

insurance

Accident cover

Predominantly

sold in group

insurance

Total premiums

collected for all

cover types was

$17.351bn

16,034

13,299

1,994

555

186

13,456

11,999

1,177

48

232

Total (all channels)

Group (inside superannuation)

Retail (advised)

Direct (non-advised)

Group (outside superannuation)

TPD cover Death cover

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 24

60 Table 4 summarises the total number of TPD claims made during the period

for each channel, highlighting the increasing dominance of the group channel.

61 During the 12 months to 31 December 2018, a total of 26,150 TPD claims

were received across all channels: 14,772 claims were accepted, 2,067 were

declined and 1,619 were withdrawn. At the end of the period 7,692 claims

were undetermined.

Table 4: TPD claims received, by channel and outcome (12 months to 31 December 2018)

Outcome

Claims—retail

Claims—direct

Claims—group

Claims—total

Received (number)

2,691

103

23,356

26,150

Accepted (number)

1,268

36

13,468

14,772

Declined (number)

197

25

1,845

2,067

Withdrawn (number)

298

10

1,311

1,619

Undetermined (number)

928

32

6,732

7,692

Accepted (percentage)

87%

59%

88%

88%

Declined (percentage)

13%

41%

12%

12%

Withdrawn (percentage)

11%

10%

6%

6%

Source: APRA, Life insurance claims and disputes statistics, December 2018 (released 27 June 2019)

Regulatory environment and gaps

ASIC’s previous work to improve outcomes for consumers

in the life insurance industry

62 ASIC published REP 498 in 2016. We identified concerns with TPD

insurance, including the following:

(a) TPD had the highest average declined claim rates—Declined rates

were particularly high for three insurers (37%, 25% and 24%, compared

to an industry average of 16%).

(b) Claims processing times were not consistent with good industry

practice—The average processing time of TPD claims for one insurer

was 21 months.

(c) High rates of withdrawn claims—TPD claims that were notified to the

insurer but did not proceed to an acceptance or decline decision were as

high as 33% for one insurer (compared to an industry average of 10%).

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 25

When claims declined and withdrawn claims are combined, only 65%

of claims notified were being paid.

(d) High rates of policy definition disputes—Over 50% of disputes about

policy definitions were about TPD products and pre-existing conditions.

63 Since the publication of REP 498 in 2016, ASIC has undertaken a range of

targeted surveillances and industry reviews to diagnose the drivers of poor

consumer outcomes in TPD insurance markets. Most importantly:

(a) We reviewed the design and sale of direct life insurance—term life,

accidental death, trauma, TPD and income protection insurance sold

directly to consumers over the phone without personal advice. In August

2018, ASIC released Report 587

The sale of direct life insurance

(REP 587). This report found that direct life insurance was often delivering

poor consumer outcomes, with high rates of lapses and declined claims.

We also identified a direct link between poor sales conduct, including

pressure selling, and poor consumer outcomes. We are now consulting on

our proposal to ban unsolicited telephone sales of direct life insurance.

Note: See Consultation Paper 317 Unsolicited telephone sales of direct life insurance

and consumer credit insurance (CP 317).

(b) We reviewed the role of superannuation trustees in insurance claims

handling and complaints. In September 2018, ASIC released Report 591

Insurance in superannuation (REP 591). This report highlighted a high

level of variation in TPD definitions used in insurance products that

pose significant challenges for consumers in understanding and

comparing insurance cover.

(c) We worked with APRA to develop the Life insurance claims and

disputes statistics publication (APRA-ASIC life claims data collection).

In March 2019, APRA and ASIC released a series of publications and

an online tool on ASIC’s MoneySmart website

allowing consumers to

compare life insurers’ performance in handling claims and disputes.

This was the first time this scale of data had been made publicly

available on an industry and individual insurer basis. This data will be

updated on an ongoing basis.

64 A timeline showing when regulatory action and other significant inquiries

and reforms took place is provided in Figure 6.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 26

Figure 6: Recent regulatory milestones in life insurance

Note: This diagram outlines the time periods for data collected in recent ASIC and APRA reviews of the life insurance industry

alongside the commencement of the relevant Life Insurance Industry Codes. For a description of the commencement of these

Codes, see paragraphs 65–71 of this report. For a description of the findings of the Royal Commission, see paragraphs 72–75.

For a description of the passage of law reform relating to the product intervention powers, see paragraphs 81–83.

The importance of robust industry codes of practice

65 Industry codes play an important part in ensuring that financial products and

services are provided fairly in Australia. Where they enjoy the support and

commitment of the sponsoring industries, codes can deliver real benefits to

consumers and those who are bound by and must comply with them.

66 All life insurers that are members of the Financial Services Council (FSC)

must comply with the Life Insurance Code of Practice (Life Code). The Life

Code came into effect on 1 October 2016 and requires life insurers and those

offering life insurance products to service their customers in a ‘timely,

honest, fair and transparent way’. Insurers were required to comply with the

Life Code from 1 July 2017.

67 The Insurance in Superannuation Voluntary Code of Practice (Insurance in

Superannuation Code) is a voluntary code of conduct for superannuation

trustees. Superannuation trustees who have opted to use this code have until

1 July 2021 to comply.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 27

68 As at the date of this report, 69 superannuation trustees have publicly

adopted the Insurance in Superannuation Code in various forms. The

superannuation industry is largely represented by the FSC, the Association

of Superannuation Funds of Australia Limited, and the Australian Institute of

Superannuation Trustees. These three bodies are the owners of the Insurance

in Superannuation Code owners and are responsible for its development.

69 The period of our review covered the first six months of the Life Code’s

implementation. Compliance with the Life Code is monitored by the Life

Code Compliance Committee. Subscribers to the code must report

significant breaches of the code to this committee and must implement

corrective measures as agreed.

70 The FSC is currently reviewing the Life Code in light of the ongoing

concerns about life insurance highlighted since the code’s implementation,

including by the report of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Corporations and Financial Services’ inquiry into the life insurance industry,

and the Royal Commission. ASIC has also provided feedback on the Life

Code, including in relation to our recommendations about the design and

sale of direct life insurance in REP 587

.

71 In Section C of this report, we identify enhancements that should be included

in the next iteration of the Life Code for claims handling practices. In

addition, we consider that the FSC needs to consult broadly and

transparently about enhancements to the Life Code.

Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking,

Superannuation and Financial Services Industry

72 The Royal Commission was established on 14 December 2017 to inquire

into past cases of misconduct. The final report was submitted to the

Governor-General and tabled in Parliament on 4 February 2019.

73 Case studies on claims handling practices in life insurance were considered

in the sixth round of hearings, held in September 2018. The case studies

examined practices that had breached financial services laws and/or caused

consumer detriment, and where conduct had fallen below community

standards and expectations.

74 In its final report, the Royal Commission made 11 specific referrals to ASIC

about eight entities. This was in addition to two referrals made during the

Commission’s hearings. ASIC will continue to work closely with all relevant

agencies, including APRA and the Commonwealth Director of Public

Prosecutions, during these investigations.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 28

75 The final report contained 15 recommendations for law reform affecting the

life insurance and general insurance industries, including the following

recommendations that are relevant for TPD insurance claims handling:

(a) Recommendation 4.6—The Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Insurance

Contracts Act) should be amended so that an insurer may only avoid a

contract of life insurance on the basis of non-disclosure or misrepresentation

if it can show that it would not have entered into a contract on any terms.

(b) Recommendation 4.7—The unfair contract terms provisions set out in the

Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (ASIC Act)

should apply to insurance contracts regulated by the Insurance Contracts Act.

(c) Recommendation 4.8—The handling and settlement of insurance

claims, or potential insurance claims, should no longer be excluded

from the definition of a financial service.

(d) Recommendation 4.9—The law should be amended to provide for

enforceable provisions of industry codes and for the establishment and

imposition of mandatory industry codes.

(e) Recommendation 4.10—The Life Code should be amended to empower

the Life Code Compliance Committee to impose sanctions on a

subscriber that has breached the Code.

(f) Recommendation 4.11—The Corporations Act should be amended to

require life insurers to take reasonable steps to cooperate with the

Australian Financial Complaints Authority in its resolution of disputes.

(g) Recommendation 4.13—Treasury in consultation with industry should

determine the practicability, and likely pricing effects, of legislating

universal key definitions, terms and exclusions for default MySuper

group life policies.

Note: See Royal Commission, Final report, February 2019, vol 1.

The need for new powers and tools to address misconduct,

consumer harm and regulatory gaps

76 ASIC has supported the expansion of our powers to address potential

misconduct and consumer harm where there are regulatory gaps.

77 Some of the most significant regulatory gaps exist where there are carve-outs

from the legislation that we administer, including the following:

(a) Claims handling exemption—Many claims handling activities do not

fall within the current definition of providing a financial service, and

others are excluded by reg 7.1.33 of the Corporations Regulations 2001

(Corporations Regulations). The exclusion restricts ASIC’s ability to

take action on claims handling conduct. In 2019 Treasury commenced a

public consultation about removing this exclusion in response to

Recommendation 4.8 of the Royal Commission.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 29

(b) Adequate available resources—The general obligation of an Australian

financial services (AFS) licensee under s912A(1)(d) of the Corporations

Act—namely, to have adequate available resources (including financial,

technological and human resources) to provide the financial services

covered by the licence and to carry out supervisory arrangements—does

not apply to life insurers that are regulated by APRA.

(c) Adequate risk management systems—The general obligation of an AFS

licensee under s912A(1)(h) of the Corporations Act to have adequate

risk management systems does not apply to life insurers that are

regulated by APRA.

78 For consumers, the intrinsic value of an insurance product lies in the ability

to make a successful claim when an insured event occurs. When insurers act

unfairly in claims handling, under the present regulatory regime, ASIC is

limited in the interventions we can take.

79 If the current legislative framework is revised, ASIC could take action for

conduct such as:

(a) incentives for claims staff and management that conflict with the

insurer’s obligation to assess each claim on its merits;

(b) inappropriate claims-handling practices;

(c) unnecessary or extensive delays in handling claims; and

(d) deficient systems and data, which give rise to conduct risk and

consumer harm.

Recent legislative reform

80 Two important pieces of legislative reform were passed in early 2019:

(a) the Treasury Laws Amendment (Design and Distribution Obligations

and Product Intervention Powers) Act 2019; and

(b) the Treasury Laws Amendment (Protecting Your Superannuation

Package) Act 2019.

Design and distribution obligations and product intervention powers

81 The product intervention powers were recommended by the Financial

System Inquiry in 2014. ASIC has long supported these reforms which

strengthen our consumer protection toolkit by equipping us with the power

to intervene where there is a risk of significant consumer detriment. The

power allows ASIC to temporarily intervene including, where necessary, to

ban a product where significant consumer detriment has occurred, will occur

or is at risk of occurring.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 30

82 The product intervention powers came into effect on 6 April 2019. ASIC did

not have these powers when this review commenced. The way in which we

could use intervention powers if necessary in the future in relation to

restrictive insurance definitions is explored in Section B of this report.

83 The design and distribution obligations will require accountability for

insurers, superannuation trustees and other financial service providers to

design, market and distribute financial products that meet consumer needs.

These obligations come into effect on 5 April 2021. The design and

distribution obligations do not apply to MySuper products.

Protecting Your Super reforms

84 The Protecting Your Super reforms apply from 1 July 2019 and prescribe

new arrangements to protect consumers’ superannuation balances from

erosion due to inappropriate insurance and fees. The main features

concerning insurance are as follows:

(a) Cancellation of insurance—Superannuation funds will cancel insurance

on accounts that are inactive for at least 16 months unless a member

opts to keep the insurance.

(b) Inactive accounts—Accounts with less than $6,000 that are inactive for

16 months will be transferred to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

The ATO will merge that account with a consumer’s active

superannuation account. If the consumer does not have another active

account, the ATO will keep the consumer’s superannuation safe.

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 31

B Poor consumer outcomes from the activities of

daily living (ADL) test

Key points

We found that claims assessed under the ADL definition in TPD policies

had extremely high declined rates. Three in five claims assessed under an

ADL test were declined and some TPD policies had declined rates above

70%, making them effectively ‘junk’ insurance.

Most of this junk insurance was held by default within superannuation. The

design of these products results in certain cohorts of consumers (e.g. casual

employees) being funnelled into ADL-only TPD cover when it may not meet

their needs.

The unsuitability of this type of restrictive TPD cover for consumers is

reflected in the high rate of declined claims for disability caused by mental

illness and musculoskeletal conditions. Consumers with these common

conditions cannot rely on the TPD cover they are paying for.

Eligibility and disability criteria for TPD cover are complex and vary between

policies. Consumers are unlikely to be aware that the ADL definition applies

to them, especially when they pay the same premium as consumers who can

access general TPD cover. Our findings support the need for removal of

overly restrictive terms and for greater standardisation of key terms across

different policies.

The significance of eligibility criteria in TPD cover

85 TPD insurance can play a vital role in consumers’ financial security and

wellbeing. When consumers experience an event that prevents them from

returning to work, TPD insurance can act as a safety net, providing a lump

sum financial payment to replace, for example, future superannuation

savings, as well as contributing to ongoing medical and rehabilitation costs.

86 However, some consumers are paying for TPD cover that they may never be

eligible to claim on, or—if they are eligible—to make a successful claim on.

Our review found that claims assessed under the restrictive definition of

‘activities of daily living’ (ADL) in TPD policies—sometimes called

‘activities of daily working’ (ADW), ‘everyday working activities’ or

similar—generally resulted in very poor outcomes for consumers.

87 We collected data on claims assessed under the ADL definition because it is

the most common of the narrow or restrictive definitions that sit alongside

the broader TPD definitions. Other examples of restrictive definitions are

‘loss of limbs’, ‘permanent loss of cognitive abilities’ and ‘loss of ability to

perform home/domestic duties’. Taken together, around 5% of all TPD

REPORT 633: Holes in the safety net: A review of TPD insurance claims

© Australian Securities and Investments Commission October 2019 Page 32

claims are assessed under these types of definitions, with ADL making up

80% of this figure. Many of our concerns also apply to the other restrictive

definitions used in TPD policies.

Finding 1: Claims assessed under the ‘activities of daily living’ test

generally result in poor outcomes, with three out of five such claims

being declined

88 The average declined rate for claims made under ADL was extremely high,