Research Department

Minnesota House of Representatives

November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax

Expenditures

The Research Department of the Minnesota House of Representatives is a

nonpartisan professional office serving the entire membership of the House

and its committees. The department assists all members and committees in

developing, analyzing, drafting, and amending legislation.

The department also conducts in-depth research studies and collects,

analyzes, and publishes information regarding public policy issues for use by

all House members.

Research Department

Minnesota House of Representatives

600 State Office Building, St. Paul, MN 55155

651-296-6753

November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax

Expenditures

This research report updates and expands on a presentation that

the tax staffs of the House Research and Fiscal Analysis

departments prepared in 2008, at the request of the chair of the

Taxes Committee, to provide committee members with

background information on tax expenditures. It is intended to

serve as a reference guide, compiling information from a variety

of sources on selected individual income tax and sales and use

tax expenditures.

Copies of this publication may be obtained by calling 651-296-6753. This document can be made

available in alternative formats for people with disabilities by calling 651-296-6753 or the

Minnesota State Relay Service at 711 or 1-800-627-3529 (TTY). Many House Research

Department publications are also available on the Internet at: www.house.mn/hrd/.

This report was prepared by Pat Dalton, Nina Manzi, and Joel

Michael, legislative analysts in the House Research Department.

Questions may be addressed to Pat at 651-296-7434; Nina at 651-

296-5204; or Joel at 651-296-5057.

Nathan Hanson and Scott Kulzer provided secretarial support.

Contents

Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1

The Tax Expenditure Concept ......................................................................... 3

Factors to Consider in Evaluating

Whether to Use Tax versus Direct Expenditures ............................................. 5

Selection of Tax Expenditures to Review ...................................................... 12

Information Provided ..................................................................................... 14

Individual Income Tax Expenditures ............................................................. 17

Sales and Use Tax Expenditures .................................................................... 91

Appendix A:

How Minnesota’s Tax Expenditures Compare with Other States ............... 144

Appendix B: The Suits Index ...................................................................... 149

Appendix C: Household Income and Population Deciles ........................... 153

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 1

Introduction

This research report provides background information on selected tax expenditures in Minnesota.

It focuses on individual income tax expenditures and sales and use tax expenditures.

Tax expenditures. The primary purpose of any tax system is to raise revenue to pay for the cost

of providing government services. However, governments also commonly use their tax systems

for other purposes. One such use is to provide targeted or special tax reductions intended to

induce taxpayers to change their behavior or to provide government benefits to certain taxpayers

to achieve a public purpose. These tax reductions are often referred to as “tax expenditures,”

reflecting that they are alternatives to direct expenditure programs to achieving these objectives.

The Department of Revenue (DOR) biennially publishes a budget or compendium of

Minnesota’s tax expenditures under a statutory mandate.

1

Information provided and organization of the report. This report is designed to provide

House members and staff some additional information on selected income and sales tax

expenditures beyond that provided in the DOR Tax Expenditure Budget. It consists of the

following:

A discussion of the tax expenditure concept and factors that legislators may wish to

consider in evaluating whether or not to use tax expenditures versus direct spending to

achieve a policy objective.

A description of the criteria that were used to select the tax expenditures covered in the

report.

The remainder of the body of the report provides the following information for each tax

expenditures covered:

Describes the tax expenditure

Lists the amount of the revenue estimated to be forgone as reported in the DOR

Tax Expenditure Budget (2012)

Describes what House Research staff understands to be the objective or purpose

of the tax expenditure

Lists commonly known direct spending programs intended to achieve the same or

similar objective or purpose to the tax expenditure. Note: For a tax expenditure

for which we did not know of a related direct spending program or of a program

that is generally available across the state, there will be no entry under this

heading for the tax expenditure.

1

Minn. Stat. § 270C.11. The DOR Tax Expenditure Budget (TEB) describes each expenditure, lists its year of

enactment and some other history, and provides an estimate of the benefits (reduced taxes) conferred on

beneficiaries of each provision.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 2

Provides information on the income distribution (or incidence) of the tax

expenditure benefits, as prepared by the Department of Revenue Research

Division staff

Provides the Suits index for repeal of the expenditure, in comparison with the

Suits index for the underlying tax

Discusses evidence from published studies by academics or governmental entities

on whether the tax expenditure is effective in achieving its purposes or objectives.

Note: For a tax expenditure for which we either do not know what the objective

or purpose was or do not have a basis (e.g., published research or other reliable

bases) for providing information on cost effectiveness, there will be no entry

under this heading for the tax expenditure.

Appendices provide information on which other states provide the selected tax

expenditures and on calculation of the Suits index, used by the Department of Revenue to

measure the progressivity or regressivity of tax provisions.

Background on preparation of the report. This research report updates and expands on a

presentation that the tax staffs of the House Research and Fiscal Analysis departments prepared

during the 2008 regular legislative session, at the request of the chair of the Taxes Committee, to

provide committee members with background information on tax expenditures. Since the

presentation was made in 2008, House Research has received and continues to receive requests

for copies of the presentation document. This report formalizes and updates that presentation

document.

Staff at the Department of Revenue prepared the incidence information included in the report, as

well as the information in the 2008 presentation.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 3

Allocative versus Distributive Features

Another way to distinguish between fundamental or

basic tax features and tax expenditures is to focus on

whether the purpose of the feature is “distributive” or

“allocative” in nature.*

Distributive features are intended to change the

distribution of the tax burden primarily for equity or

similar reasons—for example, to make the

distribution more in line with “ability to pay” or

some other concept of fairness. A distributive feature

(e.g., progressive rates or standard deduction) is a

feature of the reference tax.

By contrast, an allocative feature would divide or

allocate resources between private and public goods

or among different types of public goods—e.g.,

encouraging homeownership or reducing pollution.

Features that primarily serve allocative functions are

more likely tax expenditures than part of the

reference tax.

* This distinction is from Richard Musgrave’s classic

textbook, Public Finance in Theory and Practice; its

application to tax expenditures is suggested by Daniel N.

Shaviro, “Rethinking Tax Expenditures and Fiscal

Language,” Tax Law Review 57, no. 1 (2004).

The Tax Expenditure Concept

The primary purpose of any tax system (whether federal, state or local) is to raise revenue to pay

for the cost of providing government services. However, governments also commonly use their

tax systems for other purposes. One such use is to provide special tax reductions intended to

induce taxpayers to change their behavior or to provide government benefits to certain taxpayers

to achieve a public purpose. Often, the legislature could attempt to achieve these ends through a

direct spending program, rather than through a tax-based provision. In the 1960s and 1970s, tax

policy experts developed the concept of “tax expenditures” to describe the phenomenon of

substituting tax benefits for direct spending. It generally refers to the reductions in revenue

collections that result from deviations from a reference or normal tax of the type involved.

Identifying tax expenditures, thus,

requires agreeing upon a “reference or

normal tax”—that is, the features of the

tax (whether income, sales, property,

and so forth) that would be imposed

under generally accepted theory, if the

only purpose were to raise revenue.

Reductions in revenue collected from

this reference or normal tax—for

example, exclusions, exemptions,

deductions, preferential tax rates,

credits, deferrals, and similar—are

considered “tax expenditures.” Features

such as the regular tax rate structure,

family size adjustments (e.g., personal

and dependent exemptions for an

income tax), and exclusions that are

considered necessary for practical

reasons (e.g., the failure to tax

unrealized income) are not typically

considered tax expenditures. Since

there is not always agreement on the

theoretical basis for a tax or the practical

limits of tax administration, there may

be controversy or disagreement in

determining what is and isn’t a tax

expenditure.

A key notion underlying the tax expenditure concept is that the government is using tax-based

provisions not to raise revenues, but rather to change behavior or to distribute government

benefits to individuals or business firms. These are ends or purposes that could (and more

typically are) addressed through direct spending programs. The decision to use the tax system is

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 4

simply a policy choice to use a tax-based mechanism rather than a direct spending program.

Using a tax expenditure may have implications both for how well the tax system functions in

fulfilling its core purpose of raising revenues and how effective the expenditure is in achieving

the desired policy goals. The next section suggests some of the factors that may be relevant in

evaluating the advantages and disadvantages of using tax expenditures versus direct spending.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 5

Evaluating Tax Expenditures

Tax policy principles are not the primary

benchmarks for evaluating tax expenditures. It

is sometimes suggested that tax expenditures

should be evaluated in the same manner as basic

tax features—that is, the extent to which their

effects are consistent with the standard tax

policy principles of equity, efficiency,

simplicity, and so forth.

Our premise is that while it may be appropriate

to consider tax policy principles, it is probably

inappropriate to consider them exclusively.

That’s because tax expenditures graft

government programs onto the tax system with

purposes unrelated to raising revenues. If the

policy goal of the program or its means of

achieving that goal are inconsistent with or

unrelated to one or more tax policy principles,

they will be an inappropriate guide for

evaluating whether to use a tax or a direct

expenditure. The issue is instrumental—what is

the best method of delivering or achieving the

desired goal—not whether it is a good tax

(revenue raising) feature.

As an example, tax expenditures to encourage

charitable contributions clearly flunk a test

based on pure tax policy criteria. They reduce

vertical and horizontal equity, decrease

efficiency by requiring higher tax rates,

complicate the tax, and so forth. But no one

would suggest, given a goal of encouraging

charitable contributions, that those are the

primary criteria for evaluating whether it is

better to use a tax deduction or credit or a direct

spending program, such as providing matching

contributions.

Factors to Consider in Evaluating Whether to Use Tax

versus Direct Expenditures

Legislators and other policymakers may wish to consider some of the following factors in

deciding whether to use a tax expenditure or a direct spending program to achieve their policy

objectives:

Policy measures

Ease of administration

Behavioral effects

Tax system effects

Tax policy principles

Interaction with federal tax

Constitutional restrictions

Institutional considerations

Durability

Viability

Legislative process concerns

The discussion of whether to use a tax

expenditure or a direct spending program

assumes that there is agreement on pursuing a

specific or general policy objective and the

issue is whether it is best to do that with a tax

expenditure or a direct expenditure.

Comparison of tax expenditure and direct

spending alternatives is more straightforward

when considering a new program. In

evaluating existing tax expenditures, it is

often unclear what a prior legislature’s

objective was—if indeed it had one—in

enacting or modifying a tax expenditure. In

some instances, the tax expenditure provision

may be attributable to legislative

misperceptions about the appropriate

theoretical tax base or may simply have

followed historical practices used by the

federal government or other states when a tax

was enacted. This creates challenges in

evaluating the effectiveness of some tax

expenditures.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 6

Policy-based Measures

Ease of administration: Is it easier to administer the program as part of the tax system or

as a direct spending program?

Administrative advantages are a frequent justification for using a tax expenditure rather than a

direct spending program. For example, it might be cost prohibitive to operate a direct spending

program that provides small benefits to a large number of recipients, while if many or all of the

recipients are already filing income tax returns, it might be relatively easy to do so as a tax

expenditure. In that case there’s also a minimal burden on the taxpayers claiming the benefit,

since they are already filing an income tax return; with a direct spending program they may

instead be required to complete a separate application for the benefit. There is also evidence that

the “take-up” of benefits provided administratively through the income tax may be higher than

for direct spending programs that require a separate application.

2

But if many of the recipients

are not taxpayers or even tax filers, that diminishes the advantage of using a tax expenditure

since the administrative cost advantages will be lower. Programs that require or function best

with an element of administrative judgment or discretion typically are not good candidates for

using tax expenditures to deliver their benefits. To function effectively as a tax expenditure,

program parameters must be relatively simple and clear, so that typical taxpayers (or their tax

preparers) can correctly apply them to their circumstances.

Some factors to consider:

Are most recipients or targets of the program already taxpayers or tax filers?

How complicated are the program parameters—can they be easily self-applied by a

taxpayer or preparer or do they require the expertise of a specialist to administer?

Does it work to deliver the benefit as a lump sum (e.g., a tax refund) once a year or is it

important to more regularly provide benefits (e.g., because otherwise the recipient will be

financially unable to engage in the desired behavior)?

3

Behavioral effects: If the goal is to induce changes in behavior, will a tax provision be more

effective than a direct spending program in doing so?

A frequent goal of tax expenditures is to change behavior by providing a tax incentive or benefit.

As an alternative, a similar incentive or benefit could be delivered through a direct spending

program. For example, families paying for college costs can be given a tax credit or provided a

grant or scholarship of equal value. If the purpose is primarily to change behavior (to encourage

more individuals to attend college), a key issue may be whether a tax credit or grant is more

2

For example, there is some evidence that somewhat higher percentages of comparable households claim the

federal earned income tax credit than food stamps. See Marsha Blumenthal, Brian Erard, and Chih-Chin Ho,

“Participation and Compliance with the Earned Income Tax Credit,” National Tax Journal 53, no. 2 (2005): 207-08

3

This may not be relevant if the benefits can be delivered to taxpayers through adjustments in withholding or

for sales tax exemptions that provide their benefits when purchases are made. It is a bigger factor for benefits to be

delivered to individuals that exceed tax liability, such as refundable credits, or for extraordinary deductions or

credits that cannot be automatically reflected in income tax withholding.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 7

effective in achieving that end.

Typically, economic theory has assumed that the form or manner in which a financial incentive

(money) is provided does not matter. However, recent research in “behavioral” economics has

found that conclusion is not necessarily true; individuals are subject to various cognitive biases

that cause them to over or undervalue (on a purely mathematical basis) certain financial

mechanisms. For example, individuals assign higher values to potential financial losses than to

equivalent gains.

This behavioral insight into the power of “loss aversion” may be relevant to the choice between

tax and direct expenditures. Tax concessions allow individuals to “retain” money they already

have (i.e., to avoid a loss). In contrast, individuals may perceive receipt of a direct spending

benefit as a gain with a lower relative value, even if the dollar amounts are the same. Along

these lines, some initial research suggests that loss aversion translates to tax aversion. If these

results can be replicated, it may be that individuals, on average, value avoiding paying taxes

more highly than receiving an equal financial benefit under a direct spending program. This

would suggest (at least under some circumstances) that the state could get more bang-for-the-

buck by using a tax expenditure rather than a direct spending program, all else being equal.

These possibilities need to be validated by additional research in behavioral economics, but

could be important to the choice between the two mechanisms.

Effects on the tax system: Does the proposed tax expenditure adversely affect the basic

functioning of the revenue/tax system?

Adding tax expenditures inevitably complicates the tax system, reducing understandability and

increasing the difficulty of complying with and administering the tax. As more tax expenditures

are added, the focus of tax administrators is diverted from collecting revenue to “administering”

provisions that have purposes unrelated to raising revenues. For institutional reasons, staff at

DOR may be less sympathetic to the objectives of the tax expenditure than staff at an agency that

administers similar direct spending programs would be and this may affect how the programs are

administered.

4

Increases in the number and complexity of tax expenditures compel taxpayers to

spend more time completing their returns and familiarizing themselves with new programs often

only to find out that they’re ineligible. Sometimes competing tax expenditures for the same

purpose (e.g., the multiple federal tax expenditures for higher education costs and retirement

saving), require taxpayers to carefully determine which is the best choice for them, which further

increases the time spent preparing the return. In addition, the perception that subtractions or

credits allow others to avoid paying taxes can erode public confidence in the tax. These negative

effects should be balanced against the advantages of using the tax system to deliver the program

benefits.

4

This assumes that the DOR and its staff view their primary mission as administration of the tax system and

collection of revenue for the state. If that is true, it seems they will be less invested in ensuring that tax expenditure

programs directed at housing, long-term care, higher education, or similar are effective than the staff of state

agencies for whom that is their core mission.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 8

Application of tax policy principles: How do tax expenditures intended to further basic tax

policy goals fare when evaluated using traditional tax policy principles?

Some tax expenditures are, in fact, intended to promote basic tax policy goals. For example, the

sales tax exemption of food for home consumption was likely adopted to reduce the regressivity

of the tax. Given such a purpose, it is appropriate to assess to what extent the tax expenditure is

successful in furthering the relevant tax policy goal. For example, does the food exemption

make the sales tax more equitable or would alternative measures (e.g., a refundable credit) be

better targeted or more effective? However, as suggested in the text box on page 5, most tax

expenditures are really alternatives to direct spending and likely should not be exclusively

evaluated using basic tax policy principles, since they will nearly always violate the principles.

Interaction with federal tax: Does federal tax treatment of the program benefits favor a

tax-based or direct spending approach?

Federal income and corporate tax rules can be a factor in choosing between tax expenditures and

direct spending programs. Government benefits provided to individuals under direct state and

local spending programs, although they constitute economic income to the recipients, are

typically exempt from federal income tax under what is often called the general welfare

exclusion.

5

By contrast, if state income or property tax reductions are instead provided to

individuals who itemize deductions, the federal income tax will implicitly impose a tax on those

benefits at the recipient’s marginal rate. This occurs because a state income or property tax

reduction lowers the individual’s itemized deduction for state income or property taxes and

increases federal income tax as a result. This effect can siphon off to the federal Treasury

between 10 percent and 39.6 percent of the intended benefit, depending upon the recipient’s

marginal tax rate. A similar effect can also occur (but is less common) with regard to tax

expenditures provided to businesses. More commonly, the direct spending benefit will be treated

as income to the business, but may not if it qualifies for treatment as a contribution to capital.

6

Constitutional restrictions: Do commerce clause or other constitutional limits on state tax

powers favor using a direct spending program?

Tax and regulatory restrictions on businesses cannot discriminate against or otherwise place an

“undue burden” on interstate commerce without risking violating the commerce clause of the

United States Constitution. The Supreme Court has been fairly vigilant in ensuring that states do

not use their tax codes to favor local business interests over out-of-state businesses. By contrast,

5

The general welfare exclusion is not based on a statutory provision, but grew out of Internal Revenue Service

practices (starting with the exemption for Social Security benefits) that have been ratified by the courts. See Robert

W. Wood and Richard C. Morris, “The General Welfare Exclusion,” Tax Notes (Oct. 10, 2005), 203-09, for a

description of the exclusion. Specific statutory exclusions may also apply, such as those for scholarship income.

I.R.C. § 117.

6

I.R.C. § 118.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 9

the Court has been willing to grant states more leeway in their use of direct spending programs.

7

If a proposed tax provision—particularly one favoring in-state business interests—runs the risk

of violating the commerce clause, it is possible that a grant or other form of direct spending

program will not. This circumstance occurs less frequently for tax expenditures provided to

individuals, but can come up in that context as well. For example, it may not be possible to limit

a higher education tax credit to in-state schools, but it clearly is constitutional to do so for a

direct scholarship or grant-in-aid program.

Constitutional restrictions: Is the policy measure subject to challenge under the First

Amendment prohibition of the establishment of religion?

Contrary to the previous section, in one context, constitutional limits may favor using tax, rather

than direct, expenditures—when the legislature seeks to provide government benefits to religious

organizations, such as religious schools or other organizations. As a general rule, a taxpayer

(based only on his or her status as a taxpayer) cannot file a legal challenge to a government

program or tax provision in federal court; they don’t have legal “standing” to bring a case.

However, the U.S. Supreme Court has created a special rule that allows “taxpayer standing” in

cases challenging government programs as violating the establishment clause of the First

Amendment.

8

In a 2011 case, Arizona Christian School Tuition Organization v. Winn, the U.S.

Supreme Court held that this special standing rule does not apply to tax expenditures, such as tax

credits that assist religious schools.

9

As a result, using tax expenditures for these types of

programs may reduce the likelihood that a successful legal challenge can be brought in federal

court. However, it is unclear if the Minnesota Supreme Court will follow Arizona Christian

School in applying its standing rules in enforcing state or federal constitutional restrictions.

10

Thus, a tax expenditure arguably violating the establishment clause of either the federal or

Minnesota Constitution may be subject to a taxpayer challenge in Minnesota state courts.

7

See generally Walter Hellerstein and Dan T. Coenen, “Commerce Clause Restraints on State Business

Development Subsidies,” Cornell Law Review 81 (May 1996), 789-878, for a discussion of the constitutional

restrictions that the court has applied to the two types of subsidies in the context of business assistance.

8

Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83 (1968).

9

131 S. Ct. 1436 (2011). It was widely assumed that the Flast v. Cohen rule also applied to tax-based

assistance (i.e., tax expenditures) and several successful lawsuits were based on this assumption by the parties and

the U.S. Supreme Court. This included invalidation of a Minnesota tax credit for private school tuition. Minnesota

Civil Liberties Union v. State, 224 N.W.2d 344 (1974), cert. denied 421 U.S. 988 (1975). This followed from a case

in which the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a similar New York state tax credit in which the plaintiff relied on

taxpayer standing. Committee for Public Education and Religious Liberty v. Nyquist, 413 U.S. 756 (1973).

10

The Minnesota courts have generally taken a more permissive view of taxpayer standing than the federal

courts. See e.g., McKee v. Likins, 261 N.W.2d 566 (1977).

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 10

Institutional and Process Considerations

The previous section focused on policy-based measures for evaluating the effectiveness of using

direct versus tax expenditures. However, legislators and other policymakers are often equally or

more concerned with unrelated process or institutional dimensions of choosing between a tax

expenditure and a direct spending program—will use of a tax, rather than a direct, expenditure

make it easier to pass a program or to garner a larger amount of resources for it over time?

Durability: Tax expenditures are generally thought to receive less regular and rigorous

legislative review and, as a result, are more likely to become permanent policy features.

It is widely perceived that tax expenditures are more permanent than direct spending programs.

This flows from the common practice of making tax expenditures permanent features of the tax

law that remain in place until modified or repealed by a future legislature. By contrast, most

direct spending programs have biennial appropriations that the legislature must renew in each

budget cycle. This structure generally creates an inertial bias for retaining tax expenditures, as

compared with direct spending programs; those familiar with the legislative process recognize

that it is easier to “play defense” than offense: that is, to prevent changes in the law from being

made, as compared with passing new legislation. However, this state of affairs does not

necessarily always follow. A direct spending program could be provided a permanent, open, and

standing appropriation that does not require biennial renewal by the legislature.

11

Similarly, a

tax expenditure could be set to expire each biennium or after a certain number of years, unless

the legislature takes positive action to reenact it.

12

In any case, proponents of a policy who seek tax expenditure funding often do so because they

believe such funding is more likely to continue and be permanent than are direct appropriations

for a similarly structured program. Regardless of the features of the tax expenditure (e.g.,

whether they have sunsets or expiration clauses), this may in part flow from differences in the

institutional approaches of the tax-writing legislative committees, which may implicitly assume

tax features are permanent, compared with those of finance or appropriation committees, which

typically expect to regularly review the funding of all programs within their jurisdictions.

Visibility: Tax expenditures are not counted as explicit governmental spending.

Tax expenditures are not typically counted in the state budget (other than the tax expenditure

11

The funding for the property tax refund program, which is not generally considered to be a tax expenditure,

is provided through an open and standing appropriation. Minn. Stat. § 290A.23 (permanent open appropriation).

The funding level of the property tax refund program has rarely been carefully reviewed or modified by the

legislature in recent years. Similarly, the grant alternative to the credit for historic structure rehabilitation has an

open and standing appropriation. Minn. Stat. § 290.0681, subd. 7(b). This appropriation is permanent, although the

entire program (tax credit and grant) is subject to a sunset clause. Id., subd. 10.

12

For example, the small business investment (angel) credit sunsets after tax year 2014. Minn. Stat. §

116J.8737, subd. 12.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 11

budget) and are not included in typical national measures of state spending and taxes.

13

These

national rankings of state tax and spending amounts are often used to measure the size and

business friendliness of states. Legislators who are sensitive to those measures and concerns or

who are ideologically opposed to increases in direct or more visible state spending (and the

concomitant increases in taxes that result) may favor pursuing their policy goals through tax

expenditures, rather than through direct spending programs. This approach is inconsistent with

conventional economic theory that equates the two mechanisms, but it seems to be the practical

political reality.

14

Legislative process: Use of tax expenditures can tap other portions of the state budget to

provide expanded resources to support a policy.

Proponents of a policy or program may also promote tax expenditures as a source of additional

budget resources or a way to tap other legislative supporters for the policy or program.

Legislatures typically allocate state budget resources to finance or appropriation committees with

jurisdiction over different subject areas. These allocations may be based on incremental

increases in previous levels of funding or may be limited by other constraints. Seeking indirect

funding through the tax-writing legislative committees may provide a new or supplemental

source of funding, since tax-writing committees may have access to more state budget resources

than the relevant finance committee. In practice, this allows policy proponents to diversify their

funding options and to appeal to a different set of legislative actors.

13

We are aware of no national comparisons of the level of state and local tax expenditures across states. By

contrast, national comparisons of state and local tax and direct spending levels are regularly published (based on

data collected by the federal government) by many organizations and are widely cited.

14

High tax rates that result from tax expenditures, under economic theory, are equally distortive of private

market behavior as high tax rates that are attributable to direct spending.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 12

Pyramiding

Pyramiding occurs when a tax applies at

multiple levels of business production and

distribution. The result of this typically would

be to pass the tax along in higher prices at the

next level of production (e.g., a manufacturer

who sells to a wholesaler). The tax burden

“pyramids” or cascades at each level, so that

the total burden on the consumer is higher

than the statutory or nominal rate. Pyramiding

favors vertically integrated or larger

businesses. These businesses can minimize

the multiple levels of tax by performing

functions—that would be taxable if purchased

from a third party—with employees.

Pyramiding also undercuts statutory

exemptions (e.g., the sales tax paid by grocers

gets passed along in higher grocery prices,

despite the exemption for food products) that

are intended to reduce regressivity or exempt

necessities.

Selection of Tax Expenditures to Review

The report covers only tax expenditures under the two largest state taxes—the individual income

and general sales tax. The largest amount of the state’s tax expenditures are under those two

taxes. The report does not cover all of the tax expenditures under the two taxes; it excludes tax

expenditures from the report based on the following criteria:

Individual income tax expenditures that would be impractical to modify or reduce for

administrative or compliance reasons were excluded. This category largely consists of

items that carry over from federal law. Most of these items involve issues of timing,

valuation, reporting, and record keeping. For example, tax expenditures for depreciation

rules, pension and retirement plan rules, taxation of fringe benefits (which involve

significant valuation issues in many cases), and similar provisions are not covered. As a

practical matter, changes to these provisions would need to be addressed by Congress.

This report also excludes tax expenditures that are mandated by federal law, which the

state could not modify or reduce: the subtractions for U.S. bond interest, railroad

retirement benefits, on-reservation earnings of American Indians, and active service

military pay earned in Minnesota by nonresidents. In addition, a variety of small or more

minor tax expenditures that derive from the use of federal taxable income as the starting

point for Minnesota’s income tax are not discussed.

Under the sales tax, tax expenditures that

predominantly consist of business

purchases are excluded based on the

premise that the sales tax is intended to

be a consumption tax. Standard tax

policy principles argue that intermediate

business purchases should not be subject

to consumption taxation. This follows

from the purpose of the tax, to tax

consumption, and the principle of

horizontal equity—i.e., to tax taxable

consumption on an equal basis and only

once. Taxing business inputs causes the

sales tax to pyramid. (See the box at the

right for a description of pyramiding.)

Thus, the report does not discuss tax

expenditures that primarily apply to

intermediate business inputs. Rather, the

discussion (and incidence information)

focuses on the portion of each tax

expenditure that consists of consumer

purchases. The approach adopted by the

report follows roughly the

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 13

recommendations of 2011 Tax Expenditure Review Report, rather than the method used

in the biennial Tax Expenditure Budget.

15

Put another way, this research report follows

the view that these “exemptions” from tax are not really tax expenditures, but are

consistent with a reference tax base (see discussion on page 91) that treats the sales tax as

a consumption tax that should not apply to intermediate business purchases.

The report also does not cover the sales tax exemptions for purchases by entities, such as

governmental units or charities. The effect of repealing these exemptions on incidence is

unclear. If the exemptions were repealed, conventional wisdom suggests the sales tax

paid by the entities would be shifted to the entities’ employees as lower wages or to the

users of the entities’ services/products in higher prices. Moreover, these exemptions may

serve unclear or multiple objectives that are difficult to evaluate. While they likely

benefit mainly consumption by individuals of government and nonprofit services, some

of them comprise significant elements of business or capital inputs, the outputs of which

are taxable. One view is that these purchases should be exempt as intermediate inputs

and what should be taxable, in principle, are the services or goods produced or provided

by these entities. Following that theory, the report covers tax expenditures for sales made

by these entities to purchasers, such as the exemption for admissions to nonprofit arts

events and similar.

15

Contrast Minn. Dept. of Revenue, Tax Expenditure Review Report: Bringing Tax Expenditures Into the

Budget Process (February 2011), 11-13 (advocating treating the reference tax base for the sales tax as a

consumption tax) with Minn. Dept. of Revenue, State of Minnesota Tax Expenditure Budget Fiscal Years 2012-2015

(February 2012), 103 (treating the reference tax base as sales to the “final user” even if it is for production, not

consumption). The Tax Expenditure Budget is prepared under a statutory mandate, which contains a definition of

tax expenditure. Minn. Stat. § 270C.11, subd. 6. This definition is general and does not resolve questions such as

how to treat business inputs under the sales tax. Since enactment of the mandate in the 1980s, DOR has followed

the approach of treating sales to final users as the reference sales tax base.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 14

Information Provided

The report provides the following information for each tax expenditure:

A brief description of the provision. In many cases these descriptions borrow liberally

from the DOR Tax Expenditure Budget (2012) (TEB) or from other House Research

Department publications. For federal income tax deductions that flow through to the

definition of state taxable income and state income tax subtractions, the description notes

if the deduction or subtraction is allowed under both the regular tax and the alternative

minimum tax (AMT).

16

The dollar amount of projected revenue lost. These amounts, unless noted otherwise,

are taken from the DOR TEB. Note that TEB estimates for the sales tax include business

purchases. By contrast, the data used to prepare the incidence graphs in this publication

are limited to information on consumer purchases only (i.e., they do not include estimates

of the shifting of business purchases that would be subject to the sales tax if the tax

expenditure were repealed).

17

It is important to note that the revenue raising potential from repealing multiple tax

expenditures is not necessarily additive under the income tax. Combining repeal of two

or more tax expenditures may raise either more or less than the sum of their TEB

amounts, depending upon the type and situation. Also, in some cases, numbers from the

TEB may differ from revenue estimates prepared by DOR for a legislative proposal. For

example, TEB numbers do not take into account behavioral responses to repeal, which

revenue estimates may. Finally, the TEB numbers were prepared in 2011-12 (in most

cases using the November 2011 Minnesota Management and Budget forecast baseline).

Thus, they do not reflect the effects of changes in underlying economic conditions or the

law since then.

An objective or rationale for the tax expenditure. These are based on our knowledge

of points made by the proponents when the provisions were passed or modified or based

on conventional wisdom (e.g., from the literature); they may also include some

information on the history of the provision. In many cases, it is simply not clear what the

purpose, objective, or rationale was for some tax expenditures, and it is necessary to

speculate about possible purposes or to simply say we don’t know.

Related direct spending programs. Where we were aware of direct spending programs

that address some of the same purposes or rationales as the tax expenditures, we

16

The alternative minimum tax or AMT is an alternative tax structure with a broader tax base than the regular

income tax. Taxpayers subject to the AMT must pay the additional tax, if the AMT is higher than the regular tax.

17

The Department of Revenue’s Tax Incidence Study allocates the tax paid by businesses to households by

estimating the amount shifted to consumers, in the form of higher prices, to labor, in the form of lower wages, and to

owners of capital, in the form of lower rates of return (page 11 and also Appendix B of 2013 Tax Incidence Study).

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 15

attempted to list these.

18

The legislature may wish to consider tax expenditures and direct

expenditures focused on similar purposes together to determine the more cost-effective

way to achieve the objectives or to determine the best way to reduce or increase the

combined expenditures.

Incidence information. Most sections present a bar graph showing the distribution of

the tax expenditure by population decile and the Suits index for the expenditure. The

data underlying the graphs and the Suits index measures

19

were prepared by DOR staff in

the Research Division, using information they used in preparing the 2011 Tax Incidence

Study. The Suits index for a tax expenditure shows the impact of repealing that tax

expenditure alone, thus raising revenue. A negative Suits means that the distribution of

the tax expenditure is regressive—that is, the increased tax from its repeal, as a

percentage of income, declines as income increases. Conversely, a positive Suits means

that the increased tax from repeal of the expenditure would increase as a percentage of

income as income rises. For more information about the Suits index, see Appendix B.

For an income tax expenditure if the Suits is positive but less than the Suits for the

income tax, a simple repeal would make the income tax less progressive but the overall

system less regressive (by increasing a progressive tax). For the sales tax, a similar

comparison needs to be made to determine if repeal would make the tax more or less

regressive. Since the sales tax is more regressive than the overall Minnesota tax system,

increasing revenues from the sales tax (by repealing a sales tax expenditure) would

typically make the overall system more regressive by increasing a regressive tax.

As noted above, the incidence information is limited to consumer purchases for sales tax

items and does not include the effect of the shifting of taxes on business inputs, if such a

tax expenditure were repealed wholesale. Thus, this incidence information is most useful

in considering repeal of a tax expenditure while preserving an exemption for business

purchases.

Evidence on effectiveness in meeting objective. Where we were aware of published or

other studies by neutral observers or analysts (typically academics or government

agencies) of the effectiveness of a tax expenditure, this information is reported. In some

other instances, we added what we considered to be common-sense observations

regarding the likely effectiveness of tax expenditures. The discussion of sales tax

expenditures covers this point generically at the beginning the sales tax section and

selectively for a few tax expenditures.

18

Given our lack of knowledge about direct spending programs, these listings are incomplete. They do not

attempt to describe the direct spending programs in any detail.

19

The Department of Revenue calculated the Suits indexes for this report based on the entire population. The

resulting indexes are more accurate than the “population-decile” Suits indexes used in older versions of the Tax

Incidence Study and in the 2008 version of this presentation.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 16

How to Read the Incidence Graphs

The Department of Revenue (DOR) research staff prepared the incidence information used in the report.

The incidence information for each tax expenditure is presented in a bar graph; a sample graph with

annotation appears below.

The graphs were prepared using data from DOR’s 2011 Minnesota Tax Incidence Study (2008 tax data).

The 2.5 million households in the dataset were ranked from the household with the least income to

household with the most income, and, then aggregated into ten population deciles, each containing an

equal number of households (about 250,000). Each bar shows the percentage of the tax expenditure

received by the households in that decile. The percentages listed above each bar in the graphs sum to 100

percent. Each graph also includes a text box that identifies the decile receiving the largest share of the

benefit of the tax expenditure. For example, the sample graph shows that the tenth decile (the 10 percent

of households with the highest incomes) received 5 percent of the tax expenditure (the exemption from

income tax for Social Security benefits).

DOR ranks households using a broad income measure that includes taxable and nontaxable income

reported on individual income tax and property tax refund returns, and also workers’ compensation and

welfare income obtained from other state agencies. The first decile consists of households with income

under about $10,000; the top decile was made up of households with income over about $130,000.

Appendix C lists the components of household income and the income breakpoints for all ten population

dec

il

es.

0%

4%

11%

16%

19%

21%

15%

6%

2%

5%

0%

10%

20%

30%

12345678910

PercentofTotal

PopulationDecile

Rankedfromthe10%ofhouseholdswithleastincome(1)to10%withmostincome(10)

SharesofTaxExpenditurebyDecile

SocialSecurityBenefits

The6

th

decile receives21%ofthetaxexpenditure

forSocialSecuritybenefits.

Thebarsshowthe

percentageofthetax

expendituregoingtoeach

decile.Thepercentagesadd

to100percent.

Theinsettextboxhighlightsthe

decile thatreceivesthelargest

shareoftheexpenditure

ThepopulationdecilesrankallMinnesotahouseholdsfromthe10percent

withtheleastincometothe10percentwiththemostincome.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 17

Individual Income Tax Expenditures

Overview

Reference tax base: a tax on net income. The Tax Expenditure Budget follows the approach

that the reference tax base is “income from all sources less expenses that are reasonable and

necessary to generate that income.”

20

It is occasionally suggested that the federal income tax is

really a hybrid of an income and consumption tax. Given the selection rules set out above for

choosing tax expenditures to analyze (i.e., excluding any of the base differences that are

appropriate to a consumption style tax, such as the preferences for retirement plans), this is not

an issue. As a result, the report follows the same approach as the Tax Expenditure Budget and

treats the tax as a true income tax.

General description. The Minnesota individual income tax closely follows the federal

individual income tax, using federal taxable income as the starting point in computing its tax

base. The tax applies a progressive tax rate structure to taxable income, a measure of net income

that is adjusted for family size (by allowing deduction of personal and dependent exemption

amounts) and is reduced by a variety of deductions. Reliance on the federal income tax has

advantages and disadvantages for state policymakers. Using the federal tax base means that

taxpayers do much of the calculation necessary to complete their state return when they fill out

the federal form, making it relatively easier for taxpayers to comply with and for the state to

administer the tax. However, in order to gain those advantages, the state must regularly (usually

annually) adopt changes made by Congress to keep in close step with the federal tax.

21

With

regard to tax expenditures, the state is in a sense captive to congressional decisions, since many

preferences flow through from the federal to the state level. The state can, and often does,

disallow tax expenditures provided at the federal level, but doing so makes the state’s tax more

complicated for both taxpayers and DOR.

Historical Highlights

Minnesota’s income tax has been directly linked to federal income definitions since 1961, when

Minnesota adopted federal adjusted gross income (that is, income before “below-the-line” or

personal deductions and exemptions) as the starting point for the state tax calculation. Following

federal tax reform in 1986, Minnesota in 1987 restructured its tax to use federal taxable income

as the starting tax base, thereby also adopting federal itemized and standard deduction rules, as

well as the federal personal and dependent exemptions. Since 1987 the legislature has enacted

numerous tax expenditures, both state deductions from taxable income and state credits against

tax. The 1990s saw development of a trend in which the income tax has been co-opted as a

20

Dept. of Revenue, Tax Expenditure Budget Fiscal Years 2012-2015 (February 2012): 24.

21

The Minnesota Supreme Court has held that the state constitution does not allow the state to automatically

adopt future changes adopted by Congress. Wallace v. Commissioner of Taxation, 184 N.W. 2d 588 (Minn. 1971).

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 18

mechanism for delivering transfer payments to individuals and payments to individuals and

businesses to encourage or reward specified behaviors. In 1990, for example, the legislature

enacted a state version of the federal earned income credit, called the working family credit,

which acts as a wage supplement to individuals. The working family credit mimics a direct

transfer program in that credit amounts in excess of income tax liability are paid as refunds.

Another example is the refundable credit for K-12 education expenses, enacted in 1997. The

most recent examples of tax expenditures intended to modify behavior with refundable credits

are the 2010 enactment of the small business investment credit and historic structure

rehabilitation credit.

22

Individual Income Tax Expenditures Covered

The Minnesota individual income tax includes several categories of tax expenditures listed below

that are described in greater detail in the pages that follow:

Federal full or partial exemptions from adjusted gross income that flow through to

Minnesota

Social Security benefits

interest on Minnesota state and local government bonds

Federal deductions that reduce taxable income and flow through to Minnesota

mortgage interest

real estate and other taxes (motor vehicle registration tax)

charitable contributions

State deductions that reduce state taxable income

charitable contributions of nonitemizers

expenses of living organ donors

gain on farm property by insolvent taxpayers

K-12 education expenses

AmeriCorps education awards

elderly or disabled exclusion

military pay

Job Opportunity Building Zone (JOBZ) income

Nonrefundable state credits (only available to offset liability)

marriage credit

long-term care insurance premiums

past military service

research and development expenses

Refundable state credits (amounts in excess of liability paid as refunds)

JOBZ job creation

working family credit

child and dependent care

K-12 education expenses

22

To date, there have not been any individual claims for the historic structure rehabilitation credit.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 19

military service in a combat zone

bovine tuberculosis testing

small business (angel) investment

historic structure rehabilitation

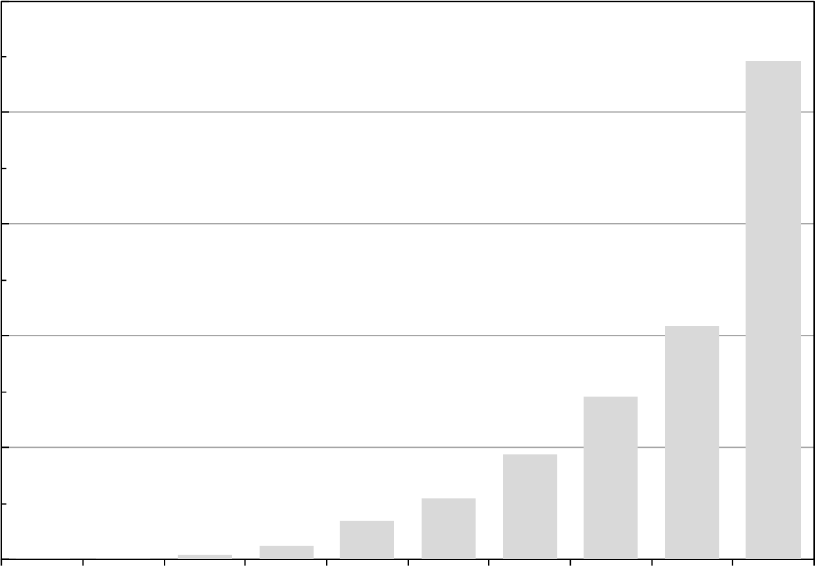

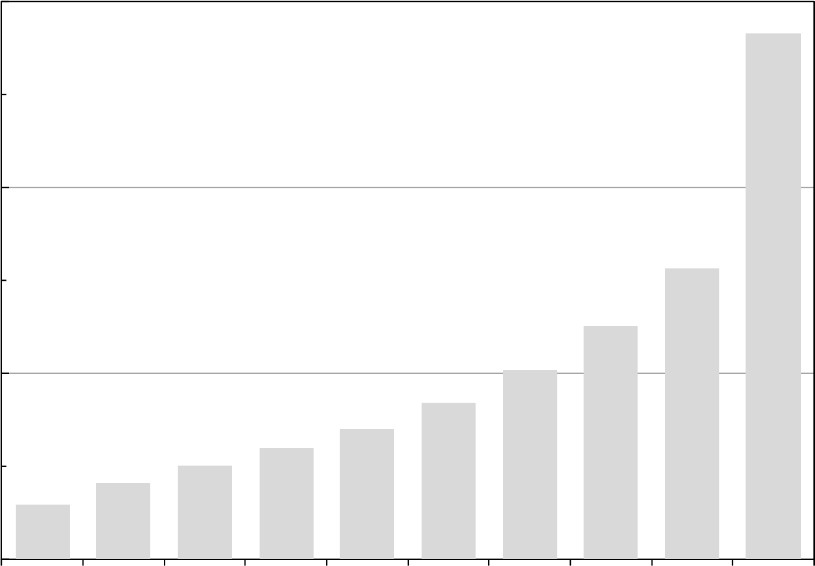

Growth in the Selected Income Tax Expenditures

The following graph shows the growth of the selected individual income tax expenditures

covered in the report relative to the growth of Minnesota personal income from fiscal year 1996

to fiscal year 2012. As the graph shows, personal income and tax expenditures have grown at

roughly similar rates over this period.

Source: Tax Expenditure Budget data; Minnesota Price

of Government

Tax Research Division

MN Department of Revenue

House Fiscal and House Research Departments

February 14, 2013

$661

$893

$1,036

$1,293

$1,336

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

$1,600

FY199 6 FY1998 FY2000 FY2002 FY2004 FY2006 FY2008 FY2010 FY2012

PersonalIncome

DollarsofSelectedIncomeTaxExpendituresComparedtoPersonalIncome

1996to2012(millions)

TaxExpenditures

$1,600

$1,200

$1,000

$800

$600

$400

$200

$0

$1,400

$112,515

$148,942

$178,147

$216,841

$241,826

$0

$50,000

$100,000

$150,000

$200,000

$250,000

$300,000

FY199 6 FY1998 FY2000 FY2002 FY200 4 FY2006 FY2008 FY2010 FY201 2

PersonalIncome

DollarsofSelectedIncomeTaxExpendituresComparedtoPersonalIncome

1996to2012(millions)

PersonalIncome

Note:2008‐2011estimatesarereporteddirectlyfromTax

ExpenditureBudget (unadjustedforchangesinforecast)

TaxExpenditures

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 20

The Selected Income Tax Expenditures Relative to the Distribution of the Tax

The following graph shows that expenditures are concentrated in the top deciles. For example,

the top two deciles (i.e., 20 percent of filers) have 46 percent of tax expenditures. However, the

income tax itself is more concentrated at the top of the income distribution than are income tax

expenditures. For example, the top decile pays 56 percent of the income tax, but receives 33

percent of income tax expenditures. Put another way, tax expenditures as a percentage of

income decline as income rises. In addition, tax expenditures are more concentrated at the

bottom of the income distribution than is tax liability. This reflects the allowance of refundable

credits, such as the working family and education credits, to households in the bottom deciles.

Source: HITS Model for 2008,

and Tax Incidence Study database

Tax Research Division

MN Department of Revenue

November 28, 2012

The remainder of this section of the report provides information on the selected individual

income tax expenditures.

2%

4%

8%

9%

7%

7%

8%

9%

13%

33%

0%

0%

0%

1%

3%

5%

7%

11%

17%

56%

‐10%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

12345678910

PercentofTotal

PopulationDecile

Rankedfromthe10%ofhouseholdswit hleastinco me(1)to10%wit hmostincome(10)

SharesofIncomeTaxandIncomeTaxExpendituresbyDecile

PercentofIncomeTaxExpenditures

PercentofIncomeTaxBurd en

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 21

Social Security Benefits

Description of Provision

Minnesota follows federal law in taxing Social Security benefits. Under these rules, up to 85

percent of Social Security benefits are subject to federal and state income tax, depending on the

taxpayer’s income. All Social Security benefits are exempt from taxable income for taxpayers

with incomes under $25,000 ($32,000 for married joint taxpayers). For incomes between

$25,000 and $34,000 ($32,000 and $44,000 for married joint taxpayers), up to 50 percent of

Social Security benefits may be subject to tax. For incomes over $34,000 ($44,000 for married

joint taxpayers), up to 85 percent of Social Security benefits may be included in taxable income.

Income for purposes of these rules is income from taxable sources, plus tax-exempt bond

interest, and one-half of Social Security benefits. The 15 percent of benefits that remain exempt

from taxation regardless of taxpayer income represents an approximate value for recovery of the

individual’s aftertax contributions to Social Security, while the up to 85 percent that may be

included in taxable income represents the employer’s contributions and transfers, neither of

which were taxable to the beneficiary.

In 2009 approximately 858,000 Minnesota residents received Social Security benefits and

excluded part or all of those benefits from taxable income.

Projected Tax Expenditure: Social Security Benefits ($ thousands)

FY 2012 FY 2013 FY 2014 FY 2015

$211,800 $220,300 $234,000 $255,100

The tax expenditure for Social Security benefits has increased in nominal terms (unadjusted for

inflation) by 33.4 percent from FY 2002 to FY 2012, compared with a 44.9 percent nominal

increase in personal income over the same time period.

Objective or Rationale

Social Security benefits became explicitly exempt from taxation under Treasury Department

rulings issued in 1938 and 1941. Larry DeWitt of the Social Security Administration’s

Historian’s Office described the rationale for the rulings as follows:

Treasury’s underlying rationale for not taxing Social Security benefits was that

the benefits under the Act could be considered as “gratuities,” and since gifts or

gratuities were not generally taxable, Social Security benefits were not taxable. It

is likely that Treasury took this view owing to the structure of the 1935 Act in

which the taxing provisions and the benefit provisions were in separate Titles of

the law. Because of this structure, one could argue that the taxes were just a form

of revenue-raising, unrelated to the benefits. The benefits themselves could then

be seen as a “gratuity” that the federal government paid to certain classes of

citizens. Although this was clearly not true in a political and moral sense, it could

be construed this way in a legal sense. In the context of public policy, most people

would hold the view that the tax contributions created an “earned right” to

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 22

subsequent benefits. Notwithstanding this common view, the Treasury

Department ruled that there was no such necessary connection and hence that

Social Security benefits were not taxable.

23

Social Security was enacted in 1935.

24

Taxes were first collected in 1937, and payment of

monthly benefits began in 1940.

25

The initial Treasury rulings on taxation of benefits were made

before any benefits had been paid. Further, individuals who would begin receiving benefits in

1940 would have paid little if anything in payroll taxes, strengthening the perspective that the

benefits were in fact a gratuity. As time went on the exemption may have come to be seen as a

way to enhance the value of the benefits, which were initially very modest. Or it may have been

viewed as a way to provide a preference to senior citizens, who at the time were, on average,

poorer than the rest of the population. The exemption treated Social Security benefits differently

from private pension income, in which the amount that exceeds the taxpayer’s contributions to

the pension is subject to taxation.

In 1983 Congress partially withdrew the total exemption from taxation, providing for up to 50

percent of benefits to be included in taxable income. The rationale for this change was two-fold:

to shore up the financing for the Social Security system since revenue raised through taxing

benefits goes into the Social Security Trust Funds, and to reverse the early Treasury rulings and

treat Social Security benefits more like private pension income.

When considering the 1983 Amendments, the Report by the House Ways &

Means Committee argued as follows: “Your Committee believes that social

security benefits are in the nature of benefits received under other retirement

systems, which are subject to taxation to the extent they exceed a worker’s after-

tax contributions and that taxing a portion of social security benefits will improve

tax equity by treating more nearly equally all forms of retirement and other

income that are designed to replace lost wages...

26

The 50 percent inclusion rate represented the employer share of the payroll tax, which is

not taxable to the employee at the time the tax is paid. However, as DeWitt observes,

“Even so, this rough-approximation did not really give Social Security benefits the same

tax treatment as private pensions—because the real “noncontributed” portion is about 85

percent of the average benefit, not 50 percent.”

27

Further, the 1983 amendments to the Social Security Act maintained the full exemption

of benefits for taxpayers with income below $25,000 ($32,000 for married joint

taxpayers), which had the effect of retaining preferential treatment of Social Security

23

DeWitt, Research Note #12: Taxation of Social Security Benefits (February 2001).

24

H.R. 7260, Pub. L. No. 271, 74th Congress.

25

Social Security Administration, Historian’s Office, Historical Background and Development of Social

Security.

26

DeWitt, Research Note.

27

Ibid.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 23

relative to private pension income.

In 1993 Congress increased the share of benefits subject to tax to 85 percent, phased in for

taxpayers with incomes over $34,000 ($44,000 for married joint taxpayers). The federal

revenues from the 1993 changes were credited to the Medicare trust fund. The House Budget

Committee described the rationale for these changes as follows:

The committee desires to more closely conform the income tax treatment of Social

Security benefits and private pension benefits by increasing the maximum amount

of Social Security benefits included in gross income for certain higher-income

beneficiaries. Reducing the exclusion for Social Security benefits for these

beneficiaries will enhance both the horizontal and vertical equity of the individual

income tax system by treating all income in a more similar manner.

28

Retaining income thresholds for including first up to 50 percent and, as income increases, up to

85 percent, of benefits in taxable income means that Social Security benefits still receive

favorable tax treatment relative to private pensions, except for higher income taxpayers. The 15

percent exclusion was likely intended, as suggested by DeWitt above, to reflect a rough

approximation of the employee’s after-tax contribution (through payroll or self-employment

taxes) to his or her benefits, similar to the tax treatment of private pensions but without going

through the actual accounting for each beneficiary. In reality, the effective contribution by

beneficiaries varies widely, depending upon earnings history of the beneficiary and spouse,

number of dependents, life expectancy, and other factors.

29

Minnesota conformed to the 1983 and 1993 federal changes both as a way to maintain the

simplicity of the Minnesota tax system and to provide revenue and added progressivity.

28

As quoted by DeWitt, ibid.

29

See e.g., Martin Feldstein and Andrew Samwick, “Social Security Rules and Marginal Tax Rates,” National

Tax Journal 45, no. 1 (March 1992), 1–22, for a discussion of how the return on Social Security taxes varies based

on demographic and other characteristics of the participants.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 24

Incidence Information

Source: HITS Model for 2008 and Tax Incidence Study database

See the box on page 16 for help in reading this graph.

Tax Research Division

MN Department of Revenue

December 4, 2012

The Department of Revenue calculated the incidence of the tax expenditure of Social Security

benefits using the assumption that 90 percent of all benefits would be taxable, with the remaining

10 percent representing recovery of amounts paid through Social Security taxes. This is generally

consistent with the estimates provided in the Department of Revenue’s Tax Expenditure Budget,

and with the method the Joint Committee on Taxation employs in preparing estimates at the

federal level.

Suits index for the tax expenditure (if repealed):

-0.606

Suits index for the existing income tax:

0.218

Suits index for the overall state and local tax system:

-0.060

0%

4%

11%

16%

19%

21%

15%

6%

2%

5%

0%

10%

20%

30%

12345678910

PercentofTotal

PopulationDecile

Rankedfromthe10%ofhouseholdswithleastincome(1)to10%withmostincome(10)

SharesofTaxExpenditurebyDecile

SocialSecurityBenefits

The6

th

decile receives21%ofthetax

expenditureforSocialSecuritybenefits.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 25

Note: Suits index values can range from -1 to +1. Negative values indicate a regressive distribution; 0, a

proportional distribution; and positive values a progressive distribution. For more information see Appendix B.

Because the Suits index for repeal of the tax expenditure for Social Security benefits is less than

the Suits index for the individual income tax (and for the overall state and local tax system),

repealing the tax expenditure would make the income tax (and the overall tax system) less

progressive.

Evidence on Effectiveness in Meeting Objective

Given the lack of clarity of the rationale for the exemption, it is difficult to assess whether the

exemption is effective in achieving those goals. The exemption does provide a substantial

economic benefit to low- and middle-income recipients of Social Security benefits, compared

with retirees who have other sources of retirement income or other individuals with incomes

from other sources.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 26

Interest on Minnesota State and Local Government Bonds

Description of Provision

Interest paid on bonds issued by Minnesota governmental units is exempt from taxation under

the federal income tax and flows through to the Minnesota tax. (Interest on bonds issued by non-

Minnesota governmental units must be added to federal taxable income and is subject to tax.)

The exemption applies to bonds to finance governmental facilities, as well as to qualifying

private activity bonds (PABs). PABs include revenue bonds issued for privately owned and used

facilities, such as housing and various other facilities permitted under federal law. Interest on

state and local bonds is generally exempt under the AMT as well as the regular tax, but interest

on some PABs may be subject to taxation under the AMT.

An estimated 80,000 returns benefited from the exemption in tax year 2011.

Projected Tax Expenditure: Interest on Minnesota Bonds

($ thousands)

FY 2012 FY 2013 FY 2014 FY 2015

$62,500 $62,000 $62,800 $66,000

The tax expenditure for interest on Minnesota state and local government bonds has increased in

nominal terms (unadjusted for inflation) by 5.2 percent from FY 2002 to FY 2012, compared

with a 44.9 percent nominal increase in personal income over the same time period.

Objective or Rationale

This provision was enacted as part of the original Minnesota income tax in 1933. Since the

1960s, Minnesota has followed federal law in determining which bonds qualify for the

exemption and/or are taxable under the AMT.

The original objective or rationale for the Minnesota provision is unclear; the exemption may

have been adopted to follow the practice under the federal income tax or to treat Minnesota

bonds as favorably as U.S. Treasury bonds (which federal law prohibits states from taxing).

Most economists assume, and proponents of continuing the exemption argue, that it now has

three purposes:

To lower the borrowing costs for state government

To provide implicit state aid to local governments through lower interest costs for their

debt

To subsidize specific “private activity” projects (e.g., housing revenue bonds issued by

MHFA and local governments and bonds issued for nonprofit organizations’ capital

projects, such as nonprofit hospitals, colleges, museums, and similar)

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 27

Related Direct Spending Programs

For state general obligation bonds, the state directly pays the interest on these bonds through

appropriations. A tax exemption is another way for the state to pay, in effect, more interest (i.e.,

the foregone state income taxes on the interest) on its bonds. With regard to interest on local

government bonds, the state pays substantial general purpose aid to cities, counties, and schools.

The state also pays debt service equalization aid to schools to offset part of the borrowing costs

of school districts.

The state appropriates money to MHFA and some other borrowers for purposes similar to the

subsidy provided through the tax exemption for some types of revenue bond interest. In

addition, some nonprofit entities (e.g., hospitals and private colleges), which are also frequent

users of tax-exempt bonds, receive some direct or indirect assistance from the state.

Incidence Information

0%

0%

0%

0%

1%

2%

3%

6%

8%

79%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

12345678910

PercentofTotal

PopulationDecile

Rankedfromthe10%ofhouseholdswith leastinco me(1)to10%withmostincome(10)

SharesofTaxExpenditurebyDecile

InterestonMinnesotaStateandLocalBonds

The10

th

decile receives79%ofthetaxexp enditure

forinterestonMinnesotastateandloc a lbonds.

Source: HITS Model for 2008,

and Tax Incidence Study database

Tax Research Division

MN Department of Revenue

November 28, 2012

See the box on page 16 for help in reading this graph.

House Research Department November 2013

A Review of Selected Tax Expenditures Page 28

Suits index for the tax expenditure (if repealed):

0.456

Suits index for the existing income tax:

0.218

Suits index for the overall state and local tax system:

-0.060

Note: Suits index values can range from -1 to +1. Negative values indicate a regressive distribution; 0, a

proportional distribution; and positive values a progressive distribution. For more information see Appendix B.

Because the Suits index for repeal of the tax expenditure for exclusion of interest on Minnesota

state and local bonds is higher than the Suits index for the individual income tax (and for the

overall state and local tax system), repealing the tax expenditure would make the income tax

(and the overall tax system) more progressive.

Calculation of the incidence assumes that holders of tax-exempt bonds would simply pay tax on

the reported interest. This overstates the amount of the tax benefit to the affected taxpayers.

Purchasers of tax-exempt bonds bear an “implicit tax” that reduces the benefit of the exemption

to them—that is, they accept lower interest payments, along with the tax exemption. Thus, it is

likely that the full tax expenditure does not accrue to holders of tax-exempt bonds; instead, the

benefit equals the tax expenditure minus the interest foregone by purchasing Minnesota tax-

exempt bonds rather than making a taxable investment. However, for some of the reasons noted