RETIREMENT

SECURITY

Shorter Life

Expectancy Reduces

Projected Lifetime

Benefits for Lower

Earners

Report to the Ranking Member,

Subcommittee on Primary Health and

Retirement Security, Committee on

Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions,

U.S. Senate

March 2016

GAO-16-354

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-16-354, a report to the

Ranking Member, Subcommittee on Primary

Health and

Retirement Security,

Committee on

Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, U

.S.

Senate

March 2016

RETIREMENT SECURITY

Shorter Life Expectancy Re

duces Projected Lifetime

Benefits

for Lower Earners

Why GAO Did This Study

An increase in average life expectancy

for individuals in the United States is a

positive development, but also requires

more planning and saving to support

longer retirements. At the same time,

as life expectancy has not increased

uniformly across all income groups,

proposed actions to address the

effects of longevity on programs and

plan sponsors may impact lower-

income and higher-income individuals

differently. GAO was asked to examine

disparities in life expectancy and the

implications for retirement security.

In this report, GAO examined (1) the

implications of increasing life

expectancy for retirement planning,

and (2) the effect of life expectancy on

the retirement resources for different

groups, especially those with low

incomes. GAO reviewed studies on life

expectancy for individuals approaching

retirement, relevant agency

documents, and other publications;

developed hypothetical scenarios to

illustrate the effects of differences in

life expectancy on projected lifetime

Social Security retirement benefits for

lower-income and higher-income

groups based on analyses of U.S.

Census Bureau and Social Security

Administration (SSA) data; and

interviewed SSA officials and various

retirement experts.

GAO is making no recommendations in

this report. In its comments, SSA

agreed with our finding that it is

important to understand how the life

expectancy in different income groups

may affect retirement income.

What GAO Found

The increase in average life expectancy for older adults in the United States

contributes to challenges for retirement planning by the government, employers,

and individuals. Social Security retirement benefits and traditional defined benefit

(DB) pension plans, both key sources of retirement income that promise lifetime

benefits, are now required to make payments to retirees for an increasing

number of years. This development, among others, has prompted a wide range

of possible actions to help curb the rising future liabilities for the federal

government and DB sponsors. For example, to address financial challenges for

the Social Security program, various options have been proposed, such as

adjusting tax contributions, retirement age, and benefit amounts. Individuals also

face challenges resulting from increases in life expectancy because they must

save more to provide for the possibility of a longer retirement.

Life expectancy varies substantially across different groups with significant

effects on retirement resources, especially for those with low incomes. For

example, according to studies GAO reviewed, lower-income men approaching

retirement live, on average, 3.6 to 12.7 fewer years than higher-income men.

GAO developed hypothetical scenarios to calculate the projected amount of

lifetime Social Security retirement benefits received, on average, for men with

different income levels born in the same year. In these scenarios, GAO

compared projected benefits based on each income groups’ shorter or longer life

expectancy with projected benefits based on average life expectancy, and found

that lower-income groups’ shorter-than-average life expectancy reduced their

projected lifetime benefits by as much as 11 to 14 percent. Effects on Social

Security retirement benefits are particularly important to lower-income groups

because Social Security is their primary source of retirement income.

Disparities in Life Expectancy Affect Lifetime Social Security Retirement Benefits

Social Security’s formula for calculating monthly benefits is progressive—that is,

it provides a proportionally larger monthly earnings replacement for lower-

earners than for higher-earners. However, when viewed in terms of benefit

received over a lifetime, the disparities in life expectancy across income groups

erode the progressive effect of the program.

View GAO-16-354. For more information,

contact

Charles Jeszeck at (202) 512-7215 or

jeszeckc@gao.gov

.

Page i GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

Letter 1

Background 3

Increasing Life Expectancy Adds to Challenges for Retirement

Planning 10

Life Expectancy Disparities Negatively Affect Retirement

Resources for Lower-Income Groups 21

Agency Comments 39

Appendix I List of Selected Studies on Life Expectancy Differences, by Income 41

Appendix II Scenario Calculation Methodology and Additional Examples 43

Appendix III Trend in the Cap on Social Security Taxable Earnings 50

Appendix IV Comments from the Social Security Administration 52

Appendix V GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 53

Related GAO Products 54

Tables

Table 1: Selected Proposals to Adjust the Social Security

Retirement Program and the Projected Effect on Social

Security’s Combined Old-Age and Survivors Insurance

and Disability Insurance Trust Funds 14

Table 2: Retirement Savings Held by Households Headed by

Individuals near or in Retirement, 2013 18

Table 3: Selected Studies’ Projected Life Expectancy over Time

for Men Approaching Retirement, by Income Group 23

Table 4: Selected Studies on Life Expectancy Differences, by

Income 41

Contents

Page ii GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

Figures

Figure 1: Trends in Number of Private Sector Defined Benefit and

Defined Contribution Plans, 1975-2013 9

Figure 2: Trend in the Annual Net Cash Flow of Social Security’s

Combined Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and

Disability Insurance Trust Funds, 1980 through 2025

(projected) 12

Figure 3: Differences in Projected Years Remaining for Men, by

Income Group 25

Figure 4: Shorter Life Expectancy Leads to Reduced Projected

Lifetime Social Security Retirement Benefits for Lower-

Income Men 30

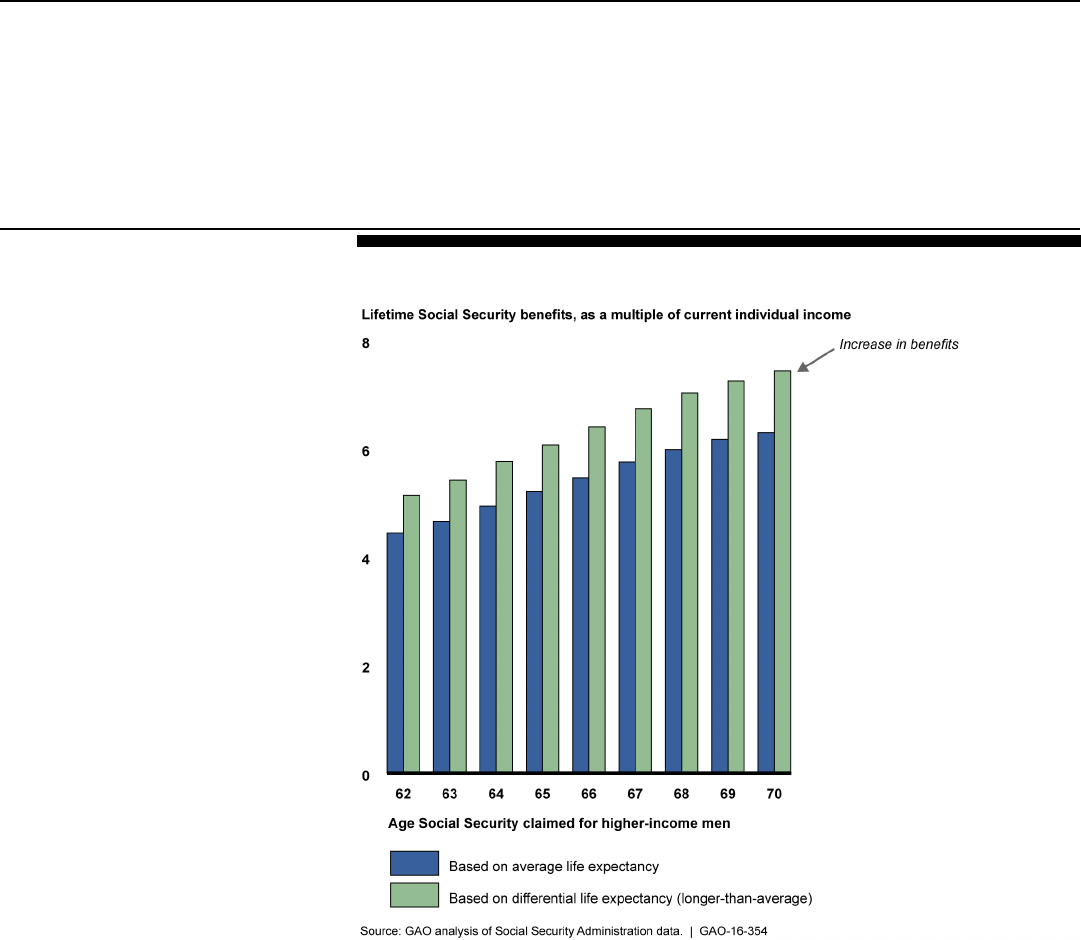

Figure 5: Longer Life Expectancy Leads to More Projected

Lifetime Social Security Retirement Benefits for Higher-

Income Men 32

Figure 6: Shorter Life Expectancy Leads to Proportionally Less

Lifetime Social Security Retirement Benefits for

Hypothetical Lower-Income Men 34

Figure 7: Present Value Adjusted Lifetime Social Security

Retirement Benefits 47

for Lower-Income Men 47

Figure 8: Present Value Adjusted Lifetime Social Security

Retirement Benefits for Higher-Income Men 48

Figure 9: Change in Present Value Adjusted Lifetime Social

Security Retirement Benefits 49

Figure 10: Percentage of Covered Earnings Subject to the Social

Security Payroll Tax, 1975-2013 51

Page iii GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

Abbreviations

AIME average indexed monthly earnings

CBO Congressional Budget Office

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Census U.S. Census Bureau

DB defined benefit

DC defined contribution

DI Disability Insurance

ERISA Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974

IRA individual retirement account

IRS Internal Revenue Service

OCACT Office of the Chief Actuary

OASI Old-Age and Survivors Insurance

PBGC Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation

SSA Social Security Administration

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

March 25, 2016

The Honorable Bernard Sanders

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Primary Health and Retirement Security

Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions

United States Senate

Dear Senator Sanders:

The increase in average national life expectancy over the past several

decades is a positive development, but also requires more planning and

saving to support longer retirements with effects on the government,

employers, and individuals. However, life expectancy has not increased

uniformly across all income groups. People who have lower incomes, for

example, can expect to have shorter lives, on average, compared to

those with higher incomes. As a result, some proposed actions to address

the fiscal effects of longevity on retirement programs and plan sponsors

may impact lower-income and higher-income individuals differently. In

light of this situation, you asked us to examine disparities in life

expectancy and the implications for our nation’s policies with respect to

retirement security. This report provides information on the following:

1. The implications of increasing life expectancy for retirement planning.

2. The effect of life expectancy on the retirement resources for different

groups, especially those with low incomes.

To explore the implications of increasing life expectancy for retirement

planning, we reviewed existing publications, including federal agency

documentation and studies on life expectancy for individuals around

retirement age conducted by various researchers and federal agencies.

We also interviewed agency officials and retirement experts, including

researchers and academics we identified through our review of longevity

studies and through expert referral. In addition, to examine the effect of

life expectancy on the retirement resources for different groups,

especially those with lower incomes, we developed scenarios to illustrate

how disparities in average life expectancy by income group can affect the

Letter

Page 2 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

average amount of lifetime Social Security retirement benefits received by

different income groups.

1

To determine our scenario assumptions, we

reviewed relevant longevity studies.

2

For our life expectancy estimates,

we relied primarily on a 2007 Social Security Administration (SSA) study

by Hilary Waldron.

3

To inform the income groupings in our scenarios

(based on the 25th and 75th individual income percentiles), we analyzed

2015 data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s (Census) Current Population

Survey. We obtained estimated monthly Social Security benefits using

SSA’s quick calculator,

4

and we estimated average lifetime Social

Security benefits by applying life expectancy estimates from SSA and

Waldron. While our report discusses various forms of retirement

resources, for our scenarios we compare only lifetime Social Security

retirement benefits against current income. We do not factor in other

retirement resources, which could include, but are not limited to, future

payments from employer-sponsored defined benefit plans, retirement

savings accounts, or housing equity. (For details on the methodology for

our scenarios, see appendix II.) We assessed the reliability of the data we

used in our scenarios by reviewing relevant documentation and

interviewing knowledgeable agency officials. We found the data to be

reliable for the purposes used in this report.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2014 to March

2016 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing

standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to

obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for

our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe

that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings

and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

1

Social Security retirement benefits are based on covered earnings from work (such as

wages and salaries). Earnings from work generally make up the bulk of income prior to

retirement. For our purposes, we grouped our scenarios by individual income rather than

earnings.

2

See appendix I for the list of relevant studies we reviewed.

3

Hilary Waldron, “Trends in Mortality Differentials and Life Expectancy for Male Social

Security-Covered Workers, by Socioeconomic Status,” Social Security Bulletin, vol. 67,

no. 3 (2007).

4

http://www.ssa.gov/oact/quickcalc/, accessed December 10, 2015.

Page 3 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

Because Americans are, on average, living longer and having fewer

children, the average age of the population is rising and that trend is

expected to continue. As of 2015, people age 65 and over accounted for

15 percent of the population, but by 2045 they are expected to comprise

more than 20 percent of the population.

5

Life expectancy is the average estimated number of years of life for a

particular demographic or group of people at a given age.

6

Life

expectancy can be expressed in two different ways: (1) as the average

number of years of life remaining for a group, or (2) as the average age at

death for a group. Life span for a particular individual within a group may

fall above or below this average. Researchers use a variety of statistical

methods and assumptions in making their estimates, such as how

longevity trends are expected to change in the future. Researchers also

may use different data sources to develop life expectancy estimates. For

example, some may use death data maintained by SSA, while others may

use Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) mortality data or

Census data.

7

5

Based on the 2015 Social Security Trustees’ Report (intermediate assumptions).

6

Life expectancy is an average for the given group, and it can be actuarially calculated

from an underlying “mortality table,” which typically consists of a “mortality rate”—the

estimated probability of death within one year at a given age—for each age. Mortality

rates can be used to estimate the number of individuals who will live to various ages: in a

typical group, individuals can be expected to live to different ages, some dying prior to life

expectancy and some living beyond life expectancy. The exact proportion of individuals

who fall short of or exceed their life expectancy is generally not 50/50, because life

expectancy is a mean, not a median. While life expectancy and mortality are related

concepts, throughout this report we discuss life expectancy because it is more relevant to

individuals’ retirement planning than the probability that they may die in a particular year.

7

SSA maintains death data—including names, Social Security numbers, dates of birth,

and dates of death—for millions of deceased Social Security number-holders. SSA

receives death reports from a variety of sources, including states, family members, funeral

directors, post offices, financial institutions, and other federal agencies. SSA shares its full

set of death data with certain agencies that pay federally-funded benefits, for the purpose

of ensuring the accuracy of those payments. For other users of SSA’s death data, SSA

extracts a subset of records, which, to comply with the Social Security Act, excludes state-

reported death data. See 42 U.S.C. § 405(r). SSA makes this subset available via the

Department of Commerce’s National Technical Information Service, from which any

member of the public can purchase the data.

Background

Demographic Shifts and

Life Expectancy

Page 4 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

As noted, life expectancy can be estimated from different initial ages,

such as from birth or from some older age. For a given population, the

earlier the starting age, the greater the remaining years of life expectancy,

but the lower the average age at death. This is because, when projected

from birth, measures of life expectancy reflect the probability of death

over one’s entire lifetime, including from childhood infectious diseases. In

contrast, life expectancy calculated at older ages, such as age 65,

generally predicts that individuals will live to an older age than when life

expectancy is calculated at birth, since the averages for older persons do

not include those who have died before that age. As a result, the average

age that will be reached from birth will be lower than the average age that

will be reached by those who have already reached age 65.

Studies have found various factors associated with disparities in life

expectancy. For example, women tend to live longer than men, although

that gap has been getting smaller, according to SSA data.

8

In addition,

65-year-old men could expect to live until age 79.7 in 1915, on average;

in 2015, they could expect to live until age 86.1—an increase of about 6.4

years. Meanwhile, 65-year-old women could expect to live until age 83.7

in 1915, on average; in 2015, they could expect to live until age 88.7—an

increase of about 5 years. Other factors that have been shown to be

associated with differences in life expectancy include income, race,

education, and geography. A recent study examined trends in life

expectancy at the county level from 1985 to 2010 and found increasing

disparities across counties over the 25-year period, especially in certain

areas of the country.

9

The lowest life expectancy for both men and

women was found in the South, the Mississippi basin, West Virginia,

Kentucky, and selected counties in the West and Midwest. In contrast,

substantial improvements in life expectancy were found in multiple

locations: parts of California, most of Nevada, Colorado, rural Minnesota,

Iowa, parts of the Dakotas, some Northeastern states, and parts of

8

Social Security Administration, Office of the Chief Actuary, “Life Tables for the United

States Social Security Area 1900 to 2100,” Actuarial Study number 120, SSA pub. No. 11-

11536 (August 2005).

9

Haidong Wang et al., “Left Behind: Widening Disparities for Males and Females in U.S.

County Life Expectancy, 1985-2010”; Population Health Metrics, vol. 11 no. 8 (2013). For

example, for men, the highest county life expectancy at birth steadily increased from 75.5

years in 1985 to 81.7 years in 2010, while the lowest county life expectancy remained

under 65. For women, the highest county life expectancy at birth increased from 81.1

years to 85.0 years, and the lowest county life expectancy remained around 73 years.

Page 5 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

Florida. The study found that while income, education, and economic

inequality are likely important factors, they are not the only determinants

of the increasing disparity across counties. Certain environmental factors,

such as lack of access to health care, and behaviors such as smoking,

poor diet, and lack of exercise, have also been shown to be associated

with shorter life expectancy.

10

In the United States, income in retirement may come from multiple

sources, including (1) Social Security retirement benefits, (2) payments

from employer-sponsored defined benefit (DB) plans, and (3) retirement

savings accounts, including accounts in employer-sponsored defined

contribution (DC) plans, such as 401(k) plans; and individual retirement

accounts (IRA).

11

10

Another recent study found that between 1999 and 2013, there was a marked increase

in the all-cause mortality of middle-aged white non-Hispanic men and women in the United

States, largely due to increasing death rates from drug and alcohol poisonings, suicide,

and chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis, especially among those with less education.

Anne Case and Angus Deaton, Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-

Hispanic Americans in the 21st century (Princeton, NJ: Woodrow Wilson School of Public

and International Affairs and Department of Economics, Princeton University, September

17, 2015). A subsequent study age-adjusted the mortality rates published in the Case and

Deaton paper and found that the study’s results held for women but not for men. Andrew

Gelman and Jonathan Auerbach, “Age-Aggregation Bias in Mortality Trends,” Proceedings

of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 113 no. 7

(National Academy of Sciences, February 16, 2016).

11

Income in retirement may also come from other sources, such as non-retirement

savings, home equity, wages, and federal assistance programs.

The U.S. Retirement

System

Page 6 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

Social Security pays retirement benefits to eligible individuals and family

members such as their spouses and their survivors, as well as other

benefits to eligible disabled workers and their families.

12

According to

SSA, in 2014 about 39 million retired workers received Social Security

retirement benefits. Individuals are generally eligible to receive these

benefits if they meet requirements for the amount of time they have

worked in covered employment—i.e., jobs through which they have paid

Social Security taxes. This includes jobs covering about 94 percent of

U.S. workers in 2014, according to SSA.

13

Social Security retirement

benefits offer two features that offset some key risks people face in

retirement: (1) they provide a monthly stream of payments that continue

until death, so that there is no risk of outliving a person’s benefits; and (2)

they are generally adjusted annually for cost-of-living increases, so there

is less risk of inflation eroding the value of a person’s benefits.

Social Security retirement benefits are based on a worker’s earnings

history in covered employment. The formula for calculating monthly

benefits is progressive, which means that Social Security replaces a

higher percentage of monthly earnings for lower-earners than for higher-

earners. As we reported in 2015, retired workers with relatively lower

average career earnings receive monthly benefits that, on average, equal

about half of what they made while working, whereas workers with

relatively high career earnings receive benefits that equal about 30

percent of earnings.

14

In 2013, SSA reported that the program provided at

12

We use the term “Social Security retirement benefits” to refer to benefits provided under

the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) program. While SSA administers other

programs, including Disability Insurance and Supplemental Security Income, our focus is

on retirement benefits. For more about Social Security programs, see GAO, Social

Security’s Future: Answers to Key Questions, GAO-16-75SP (Washington D.C.: October

2015). In this report, for ease of reference, we use the term “worker;” however, many

individuals may no longer be working at the time they receive benefits and others, such as

dependents and survivors of workers who contributed to Social Security, may never have

worked in covered employment.

13

According to SSA, workers excluded from coverage include certain employees of

federal, state, and local governments, certain workers with very low net earnings from self-

employment, and railroad workers. About one-fourth of public-sector employees do not

pay Social Security taxes on the earnings from their government jobs and are not entitled

to any Social Security benefits based on this work.

14

This example is based on hypothetical workers born in 1985 and retiring at age 65 in

2050. The career-average level of earnings for each hypothetical worker was based on a

percentage of Social Security’s national average wage index. The low and high earners

had earnings about 45 percent and 160 percent of the national average wage index

($21,054 and $74,859, respectively, for 2014). See GAO-16-75SP.

Social Security

Social Security Benefit Formula

Social Security retirement benefits are

generally derived from an individual’s average

indexed monthly earnings (AIME). For

retirement benefits, the AIME is based on the

worker’s highest 35 years’ earnings for which

they paid Social Security taxes, and those

earnings are indexed to changes in average

wages over the worker’s career.

For 2016, the benefit formula replaces:

• 90% of the first $856 of AIME,

• 32% of AIME over $856 and up to

$5,157, and

• 15% of AIME over $5,157.

These “bend points” are also indexed for

changes in average wages.

Source: GAO analysis of Social Security Administration

documents. | GAO-16-354

Page 7 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

least half of retirement income for 64 percent of beneficiaries age 65 or

older in 2011 and that 35 percent of beneficiaries in this age range

received 90 percent or more of their income from Social Security.

For retired workers, Social Security pays full (unreduced) benefits at the

full retirement age, which ranges from 65 to 67 depending on an

individual’s birth year. Workers can claim Social Security retirement

benefits as early as age 62, resulting in a reduced monthly benefit, or can

delay claiming after they reach full retirement age, resulting in an

increased monthly benefit until age 70 (i.e., no further increases are

provided for delayed claiming after age 70). According to SSA

documentation, the Social Security benefit formula adjusts the amount of

monthly benefits to reflect the average remaining life expectancy at each

claiming age. More specifically, benefits are adjusted up or down based

on claiming age so that, on average, the actuarial present value of a

beneficiary’s total lifetime benefits is about the same regardless of

claiming age.

15

For example, workers currently age 62 who would reach

full retirement age at 66 would receive a monthly benefit about 25 percent

lower if claiming early, at age 62, compared with the benefit that would be

paid at their full retirement age. Those delaying claiming until age 70

would receive about 32 percent more per month than their full retirement

age benefit, according to SSA.

Despite higher monthly benefits for those who delay claiming, in 2014,

age 62 was the most prevalent age to claim Social Security retirement

benefits: About 37 percent of total retired worker benefits awarded were

awarded at age 62.

16

When workers die before reaching age 62, they

may not receive any of the Social Security retirement benefits that they

would have been entitled to receive had they lived longer.

17

In cases

15

An actuarial present value takes into account both life expectancy and the time value of

money (payments sooner are worth more than payments later). For more on these

adjustment factors, see GAO-16-75SP.

16

Total benefits awarded include disability benefits that convert to retirement benefits at

the worker’s full retirement age. Calculated from the Annual Statistical Supplement to the

Social Security Bulletin, 2015, table 6.A4. The share of people claiming at age 62 varies

by birth cohort, and while age 62 remains the most prevalent claiming age, the share of

people claiming at age 62 has decreased with successive birth cohorts. See GAO,

Retirement Security: Challenges for Those Claiming Social Security Benefits Early and

New Health Coverage Options, GAO-14-311 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 23, 2014).

17

The CDC reported that nearly 25 percent of the U.S. deaths in 2011 were among people

age 25 to 65.

Page 8 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

where a worker dies before or during retirement, there are survivors

benefits that provide widows and widowers up to 100 percent of the

deceased spouse’s benefit.

18

Defined benefit (DB) plans are generally tax-advantaged retirement plans

that typically provide a specified monthly benefit at retirement, known as

an annuity, for the lifetime of the retiree.

19

Qualified private sector DB

plans may be single-employer or multiemployer plans.

20

Single-employer

plans make up the majority of private sector DB plans (about 94 percent)

and cover the majority of private sector DB participants (75 percent of

about 41.2 million workers and retirees in 2014).

21

The amount of the

annuity provided by a DB plan is determined according to a formula

specified by the plan, and is typically based on factors such as salary,

years of service, and age at retirement. Plan sponsors generally bear the

risks associated with investing the plan’s assets and ensuring that

sufficient funds are available to pay the benefits to plan participants as

they come due.

22

As indicated in figure 1, over the past several decades

employment-based retirement plan coverage, especially in the private

sector, has shifted away from DB plans to defined contribution (DC)

18

Children meeting certain eligibility criteria, including those who are under 18 or disabled,

may also receive survivors benefits.

19

To receive tax-advantaged treatment, DB and DC plans must meet certain requirements

specified in the Internal Revenue Code and the Employee Retirement Income Security Act

of 1974, as amended (ERISA). Such plans are called qualified plans. Qualified DB plans

also generally must provide for an annuity for an eligible surviving spouse. In general,

ERISA applies only to plans sponsored by private sector employers.

20

Multiemployer plans are established through collective bargaining agreements between

labor unions and two or more employers, and plan assets are maintained in a single

account. Multiemployer plans should not be confused with multiple-employer plans, which

are a category of single-employer plans. Multiple-employer plans are typically established

without collective bargaining agreements. Multiple-employer DB plans must be funded as

if each participating employer were maintaining a separate plan.

21

PBGC, 2013 Pension Insurance Data Tables, see http://www.pbgc.gov/prac/data-

books.html

22

To reduce plan liabilities, some DB plan sponsors have offered participants the option of

replacing their annuity with a lump sum payment, so that the participants assume the risks

of managing the funds, and outliving the funds, themselves. See GAO, Private Pensions:

Participants Need Better Information When Offered Lump Sums That Replace Their

Lifetime Benefits, GAO-15-74 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 27, 2015).

Defined Benefit Plans

Page 9 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

plans, which generally require participants to bear the risks of managing

their assets.

23

Figure 1: Trends in Number of Private Sector Defined Benefit and Defined

Contribution Plans, 1975-2013

Retirement savings accounts can provide individuals with a tax-

advantaged way to save for retirement, but, unlike DB plans, they

generally require individuals to manage their own assets. There are two

primary types of retirement savings vehicles: employer-sponsored DC

plans, such as 401(k)s, and individual retirement accounts (IRA).

24

DC

plans’ benefits are based on contributions made by workers (and

23

While figure 1 describes pension plans with 100 or more participants, the trend is similar

when comparing all pension plans.

24

As previously mentioned, qualified DC plans must meet certain requirements in ERISA

and the Internal Revenue Code. In addition, to receive tax-advantaged treatment, IRAs

must meet certain requirements in the Internal Revenue Code.

Retirement Savings Accounts

Page 10 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

sometimes by their employers) and the performance of the investments in

participants’ individual accounts. Workers are generally responsible for

determining their contribution rate, managing their savings and

investments, and deciding how to draw down their assets after

retirement.

25

There are also tax-advantaged retirement savings accounts that are not

employer-sponsored, such as traditional IRAs and Roth IRAs. Eligible

individuals may make contributions to traditional IRAs with pre-tax

earnings and any savings in traditional IRAs are tax-deferred—that is,

taxed at the time of distribution. Eligible individuals’ contributions to Roth

IRAs are made with after-tax earnings and are generally not taxed at the

time of distribution.

26

Individuals may choose to roll over their employer-

sponsored DC plans into an IRA when they leave employment.

27

The projected continuing increase in life expectancy for both men and

women in the United States contributes to longevity risk in retirement

planning. For the Social Security program and employer-sponsored

defined benefit plans, longevity risk is the risk that the program or plan

assets may not be sufficient to meet obligations over their beneficiaries’

lifetimes. For individuals, longevity risk is the risk that they may outlive

any retirement savings they are responsible for managing, such as in a

DC plan.

25

However, employers that sponsor tax-qualified plans are subject to requirements in

administering the plan, including certain fiduciary responsibilities.

26

Both traditional and Roth IRAs are subject to various requirements such as annual

contribution limits, and Roth IRAs are subject to annual income limits.

27

For more information about 401(k) rollovers, see GAO, 401(K) Plans: Labor and IRS

Could Improve the Rollover Process for Participants, GAO-13-30 (Washington, D.C.: Mar.

7, 2013).

Increasing Life

Expectancy Adds to

Challenges for

Retirement Planning

Page 11 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

Increasing life expectancy adds to the long-term financial challenges

facing Social Security by contributing to the growing gap between annual

program costs and revenues.

28

Although life expectancy is only one factor

contributing to this gap, as individuals live longer, on average, each year

there are more individuals receiving benefits, adding to the upward

pressure on program costs.

According to the 2015 report from the Board of Trustees of the Federal

Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) and Federal Disability Insurance

(DI) Trust Funds, the Social Security OASI trust fund is projected to have

sufficient funds to pay all promised benefits for nearly two decades, but

continues to face long-term financial challenges. In 2010, program costs

for the combined OASI and DI trust funds began exceeding non-interest

revenues and are projected to continue to do so into the future (see fig.

2). The 2015 Trustees Report projected that the OASI trust fund would be

depleted in 2035, at which point continuing revenue would be sufficient to

cover 77 percent of scheduled benefits.

29

28

We recently examined the challenges facing the Social Security retirement and disability

programs. GAO-16-75SP.

29

The 2015 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors

Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds (Washington D.C.: July 22, 2015).

Increasing Life

Expectancy Adds to

Challenges for Social

Security

Page 12 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

Figure 2: Trend in the Annual Net Cash Flow of Social Security’s Combined Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability

Insurance Trust Funds, 1980 through 2025 (projected)

Notes: Non-interest revenues are revenues from payroll taxes, taxation of benefits, and

reimbursements from the general fund of the U.S. Department of the Treasury. Total costs include

benefit payments, administrative costs, and Railroad Retirement Board interchange costs. (Interest

revenue is excluded.) Changes made by the Social Security Benefit Protection and Opportunity

Enhancement Act of 2015 may affect these figures. For further information about operations of the

combined trust fund, see The 2015 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age

and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds, 158-159,

https://www.socialsecurity.gov/OACT/TR/2015/.

To help address the long-term financial challenges facing the Social

Security retirement program, various changes have been made over the

years. For example, the Social Security Amendments of 1983 established

a phased-in increase in the full retirement age, gradually raising it from

age 65 (for workers born in 1937 or earlier) to age 67 (for workers born in

Page 13 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

1960 and later).

30

Also, challenges facing the DI trust fund have affected

OASI. For example, in late 2015, Congress passed a law that reallocates

some tax revenue from the OASI trust fund to the DI trust fund, thus

delaying benefit reductions to DI beneficiaries that were projected to

occur in 2016 until 2022.

31

In addition, a wide range of options to adjust Social Security further have

been proposed. To illustrate this range of options, table 1 provides

examples from among the options and summarizes their effect according

to SSA’s Office of the Chief Actuary (OCACT).

32

Some options would

reduce benefit costs, such as by making adjustments to the retirement

age. Other options would increase revenues, such as by making

adjustments to payroll tax contributions.

33

The table shows the most

recent OCACT analysis, which is based on the intermediate assumptions

of the 2015 Trustees Report and reflects the impact on both the OASI and

DI trust funds combined over the next 75 years. The trustees estimate

that, using intermediate projections, the shortfall toward the end of their

75-year projections would reach 4.65 percent of taxable payroll for 2089.

The options are based on proposals introduced in Congress or suggested

by experts, but are not exhaustive.

34

Each has advantages and

30

According to SSA, throughout the program’s history there have been many changes

intended to increase revenues or reduce expenditures and thereby secure the program.

For example, according to SSA, the tax contribution rate for employees, employers, or

self-employed workers has increased more than 20 times. In addition, changes have been

made to benefits and to cost-of-living adjustments, such as those made by the Social

Security Amendments of 1977 and 1983.

31

The Social Security Benefit Protection and Opportunity Enhancement Act of 2015,

among other things, increased the proportion of the employer and employee tax

contributions to the trust funds that specifically go to the DI trust fund from 1.8 percent to

2.37 percent starting in 2016 through the end of 2018. Pub. L. No. 114-74, tit. VIII, 129

Stat. 584, 601-20. The combined payroll tax remains at 12.4 percent of covered earnings.

32

Social Security Administration Office of Chief Actuary, Summary of Provisions That

Would Change the Social Security Program (Sept. 16, 2015).

33

For more information on payroll tax contributions, see appendix III.

34

Readers interested in a more detailed compendium of proposed changes to the Social

Security programs may refer to the website of the Social Security Administration Office of

the Chief Actuary. The Office of the Chief Actuary has prepared memoranda for many of

the policy options, which include analyses showing the estimated effect of the changes on

the financial status of the Social Security programs. See

http://www.ssa.gov/OACT/solvency/provisions/index.html.

Page 14 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

disadvantages, and GAO is not recommending or endorsing the adoption

of any of the specific options presented.

35

Table 1: Selected Proposals to Adjust the Social Security Retirement Program and the Projected Effect on Social Security’s

Combined Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance Trust Funds

Adjustments to the retirement age

•

Continue to increase the full retirement age. According to the Office of the Chief

Actuary’s (OCACT) most recent estimates, raising the full retirement age, beginning

in 2022, by one additional month every 2 years until the retirement age reaches 68

would eliminate 13 percent of the shortfall over the next 75 years.

• Increase the age at which early claiming can take place. OCACT estimates that

raising the early retirement age, starting in 2017, by 2 months each year and ending

in 2034 (ending with the early retirement age at 65) would increase the shortfall by 2

percent over 75 years, due to a corresponding rise in costs for the disability program.

Adjustments to the structure of

retirement benefits

•

Reduce monthly retirement benefits for all retirees. OCACT estimates that reducing

benefits by 3 percent for newly eligible beneficiaries, beginning in 2016, would

eliminate 14 percent of the shortfall over 75 years.

• Reduce initial monthly retirement benefits for those with higher lifetime earnings.

OCACT provides estimates for several progressive price indexing proposals that

reduce benefits for the top category of earnings, for example, reducing the rate at

which benefits are awarded for earnings over the 30th, 40th, 50th or 60th percentile.

The effect of such proposals depends upon the reduction in rate and the point at

which that reduction is applied. OCACT estimates that the proposals they examined

would eliminate 26 to 55 percent of the shortfall over the next 75 years.

Adjustments to payroll tax

contributions

•

Increase the combined payroll taxes for employers and employees (currently 12.4

percent of covered earnings). OCACT examines several options for increasing the

payroll tax rate, with the most significant effect coming from raising the tax rate to

15.2 percent in 2028-2057 and to 18 percent in 2058 and later. That proposal is

estimated to eliminate 110 percent of the shortfall over the next 75 years.

• Eliminate the maximum taxable earnings (currently set at $118,500). OCACT also

examines a number of options for eliminating the taxable maximum. For example,

eliminating the taxable maximum, beginning in 2016, and providing benefit credit for

earnings above the current maximum would eliminate 71 percent of the shortfall over

the next 75 years.

Source: GAO analysis of Social Security Office of Chief Actuary report, 2015. | GAO-16-354

Notes: Estimates of effects are based on the intermediate assumptions of the 2015 Trustees Report

and reflect the impact on the combined trust funds over the next 75 years. We are not recommending

or endorsing the adoption of any particular policy option or package of options.

35

For example, in 2010, we reported that raising the age for early claiming of the Social

Security retirement benefit may put additional stress on the DI trust fund. See GAO, Social

Security Reform: Raising the Retirement Ages Would Have Implications for Older Workers

and SSA Disability Rolls, GAO-11-125 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 18, 2010).

Page 15 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

Although there are many factors at play in the decline of defined benefit

(DB) plans, increasing life expectancy adds to the challenges these plans

face by increasing the financial obligations needed to make promised

payments for their beneficiaries’ lifetimes.

36

For example, plan sponsors

and industry experts estimate that the Society of Actuaries’ 2014 revised

mortality tables, if adopted for DB plans, would increase plan obligations

by 3.4 to 10 percent, depending on the characteristics of a plan’s

participants.

37

As of 2012, more than 85 percent of single-employer DB

plans were underfunded by a total of more than $800 billion, according to

the most recent data available from the Pension Benefit Guaranty

Corporation (PBGC).

38

DB plan sponsors have increasingly been taking

steps, known as “de-risking,” to either reduce risk or shift risk away from

sponsors, often to participants. De-risking can be classified as internal or

external.

39

Internal de-risking approaches include reducing risk by (1) shifting plan

assets into safer investments that better match certain characteristics of a

plan’s benefit liabilities, and (2) restricting growth in the size of the plan by

restricting future plan participation or benefit accruals, such as by

“freezing” the plan (variations of which include closing the plan to newly-

hired workers or eliminating the additional accrual of benefits by those

already participating in the plan). In 2012, more than 40 percent of single-

employer DB plans were frozen in some form, according to the most

recent data available from PBGC, and many frozen plans are ultimately

terminated, which can shift the risk of ensuring an adequate lifetime

retirement income to individuals, as discussed below.

36

Sponsors of DB plans are also responsible for managing financial risks, such as

fluctuations in the value of plan assets and in interest rates, either of which can cause

volatility in the plan’s funded status and plan contributions.

37

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) prescribes and periodically revises mortality tables

to be used by qualified DB plans to calculate the plans’ funding target and other funding

calculations. The current mortality tables are based, in part, on mortality tables developed

by the Society of Actuaries in 2000. IRS expects to issue proposed regulations revising

the mortality tables for future years and has solicited comments on this issue, including on

the 2014 revised Society of Actuaries tables. IRS Notices 2013-49 and 2015-53.

38

Single-employer plans covered 75 percent of DB participants in 2014. PBGC, 2013

Pension Insurance Data Tables, http://www.pbgc.gov/prac/data-books.html.

39

For qualified DB plans, any de-risking actions must comply with requirements in ERISA

and the Internal Revenue Code in order to maintain their tax-advantaged status.

Increasing Life

Expectancy Adds to

Challenges for Defined

Benefit Plans

Page 16 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

External de-risking involves closing the plan completely (referred to as

terminating the plan) or reducing the size of the plan by transferring a

portion of plan liabilities, plan assets, and their associated risk to external

parties—typically either to participants or to an insurance company. For

example, an employer may terminate its DB plan, if it can fund all of the

benefits owed through the purchase of a group annuity contract from an

insurance company (sometimes called a “group annuity buy-out”).

40

Short

of termination, an employer can also transfer a portion of plan assets and

liabilities to an insurance company for a certain group of plan participants,

such as former employees with vested benefits.

41

Alternatively, an

employer may, under certain circumstances, terminate its DB plan by

paying all the benefits owed in another form, such as by providing a lump

sum to each participant or beneficiary of the plan, if the plan permits. The

employer could also opt to make a lump sum buy-out offer only to certain

plan participants.

42

When such an offer is made, plan participants have a

specified amount of time, known as the lump sum “window,” to choose

between keeping their lifetime annuity or taking a lump sum. Participants

40

Such actions are referred to as “standard terminations.”

41

Once responsibility is transferred to an insurance company, the participant’s rights and

protections are circumscribed by the annuity contract, the financial status of the issuer,

and state guarantees, rather than the protections under ERISA, although in some cases,

ERISA provisions may be incorporated into the annuity contract. In general, once the

transaction is complete, the participant will receive an annuity certificate from the

insurance company, and then will receive payments from that insurer, with protections

from the state insurance system and state guaranty associations. See 2013 ERISA

Advisory Council Report, Private Sector Pension De-risking and Patient Protections.

42

Until recently, DB plan sponsors were offering lump sum payments to participants who

were receiving annuity payments (known as “lump sum window offers”). On July 9, 2015,

IRS issued a notice stating its intent to prohibit these lump sum window offers, effective as

of the date of the notice, and stating that the regulations would be amended accordingly.

According to agency officials, other instances of accelerated benefit payments, including

lump sum buyouts to participants who were separating from employment but had not yet

begun collecting their benefits, and those allowed pursuant to the regulations under

Internal Revenue Code section 401(a)(9), were unaffected by the notice. The notice also

allowed for the continuation of certain lump sum window offers already in process. IRS

Notice 2015-49.

Page 17 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

who accept the lump sum assume all of the risk of managing the funds for

the remainder of their lives.

43

A key reason that individuals face challenges in planning for retirement is

that many people do not understand their life expectancy, the number of

years they will likely spend in retirement, or the amount they should save

to support their retirement. For example, a survey conducted by the

Society of Actuaries showed that there is a greater tendency for retired

respondents to underestimate rather than overestimate their life

expectancy.

44

In addition, many individuals will live beyond their life

expectancy in any case, since it is an average. Further, as we reported in

2015, older workers tend to retire sooner than they expected. Coupled

with increasing life expectancy, this means they will likely spend more

years in retirement than anticipated.

45

In 2015, more than a third of

workers surveyed by the Employee Benefit Research Institute reported

that they expected to retire at age 66 or later and an additional 10 percent

expected to never retire; however, only 14 percent of current retirees

reported that they retired after age 65. Similarly, 9 percent of workers said

they expected to retire before age 60, while 36 percent of current retirees

reported they retired earlier. The median age of retirement reported was

age 62.

46

Additionally, only 48 percent of those surveyed had calculated

how much in savings they would need for retirement.

47

43

In a previous report, we found that while comprehensive data on lump sum window

offers were not available, experts generally agreed that use of such offers was becoming

more frequent. GAO-15-74. Since this report was published, IRS issued a notice,

described previously, that generally prohibits lump sum window offers for those

participants already receiving benefits from a DB plan, without affecting other allowed

lump sum payments from a DB plan. Thus, any current expectation of future lump sum

window offers would likely be limited to separated vested employees (i.e., former

employees) who are not currently receiving benefits under a DB plan. IRS Notice 2015-49.

44

Society of Actuaries, Key Findings and Issues: Longevity, 2011 Risks and Process of

Retirement Survey Report (June 2012).

45

GAO, Retirement Security: Most Households Approaching Retirement Have Low

Savings, GAO-15-419 (Washington, D.C.: May 12, 2015).

46

This broadly aligns with SSA data on when individuals claim Social Security retirement

benefits. See GAO-14-311.

47

Employee Benefit Research Institute, The 2015 Retirement Confidence Survey: Having

a Retirement Savings Plan a Key Factor in Americans’ Retirement Confidence (April

2015).

Increasing Life

Expectancy Adds to

Challenges for Individuals’

Retirement Planning

Page 18 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

Beyond underestimating life expectancy, individuals preparing for

retirement face a number of additional challenges in accumulating

retirement savings sufficient to sustain them for their lifetime. In previous

work we found that many households near or in retirement have little or

no retirement savings (see table 2).

48

Nearly 30 percent of households

headed by individuals age 55 and older have neither retirement savings

nor a DB plan.

Table 2: Retirement Savings Held by Households Headed by Individuals near or in Retirement, 2013

Households headed by

individuals age 55-64

Households headed by

individuals age 65-74

Households headed by

individuals age 75 and older

Percent with no retirement savings

41

52

71

Percent with retirement savings

59

48

29

median amount saved

$104,000

$148,000

$69,000

equivalent inflation-adjusted annuity

$310 per month

(for a 60-year-old)

$649 per month

(for a 70-year-old)

$467 per month

(for an 80-year-old)

Source: GAO analysis of 2013 Survey of Consumer Finances data. | GAO-16-354

About half of private sector employees do not participate in any employer-

sponsored retirement plan.

49

In previous work, we found that among

those not participating, 84 percent reported that their employer did not

offer a plan or they were not eligible for the program their employer

offered.

50

Those that do participate in employer-sponsored retirement

plans are increasingly offered access only to DC plans, which—unlike DB

plans—do not typically provide a guaranteed monthly benefit for life. For

many of these participants, the level of savings accumulated in their DC

retirement accounts at the time they leave the workforce will not be

48

We also found that more than 70 percent of households headed by individuals age 55-

64 also carry debt. GAO-15-419.

49

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in

the United States (March 2015).

50

See GAO, Retirement Security: Federal Action Could Help State Efforts to Expand

Private Sector Coverage, GAO-15-556 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2015).

Page 19 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

sufficient to sustain their retirement.

51

Moreover, employer-sponsored DC

plans typically offer only an account balance at retirement, leaving

participants to identify longevity risks and manage how they will draw

down their funds over the course of their retirement.

52

To help address individuals’ difficultly in estimating their life expectancy

and the resources needed to avoid outliving their savings, the federal

government, plan sponsors, and others have developed certain tools to

aid with retirement planning. For example, benefits calculators assist

participants in translating their savings into potential annual retirement

income. One such calculator, available on the U.S. Department of Labor’s

website, assumes survival to age 95, which is beyond the average life

expectancy for individuals currently age 65.

53

To encourage saving

among those who lack access to employer-sponsored plans, in

November 2015, myRA, a federal government-managed retirement

savings program, was opened to individuals below a certain income

threshold.

54

Also, as we reported in 2015, a number of states are

exploring strategies to expand private sector coverage for people who

51

Women are particularly at risk of outliving their savings because they live longer, on

average, than men, although the gap between the sexes is diminishing. Additionally, as

discussed in previous reports, women who participate in DC plans contribute less to their

plans. Women age 65 and over have less retirement income, on average, and live in

higher rates of poverty than men in that age group. See GAO, Retirement Security:

Women Still Face Challenges, GAO-12-699 (Washington, D.C.: July 19, 2012) and GAO

Retirement Security: Older Women Remain at Risk, GAO-12-825T (Washington, D.C.:

July 25, 2012).

52

In 2012, we reported that annuities are complex, represent some risks to consumers,

and require them to make multiple complex decisions. See GAO, Retirement Security:

Annuities with Guaranteed Lifetime Withdrawals Have Both Benefits and Risks, but

Regulation Varies across States, GAO-13-75 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 10, 2012).

53

The U.S. Department of Labor offers two calculators:

http://askebsa.dol.gov/retirementcalculator/ui/general.aspx and

http://www.dol.gov/ebsa/regs/lifetimeincomecalculator.html. More calculators are available

from financial services companies and others. We recently recommended that the

Secretary of Labor take action to help workers make appropriate adjustments to the

replacement rates used in calculating their specific retirement income needs. This

included modifying the U.S. Department of Labor’s retirement planning tools. See GAO,

Retirement Security: Better Information on Income Replacement Rates Needed to Help

Workers Plan for Retirement, GAO-16-242 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 1, 2016).

54

The U.S. Department of the Treasury created a new nonmarketable, electronic savings

bond for the myRA program, which allows eligible individuals to establish Roth IRAs.

MyRA allows individuals to make one-time contributions or set up recurring contributions

(which can be deducted from their wages) that will be invested in these savings bonds.

Page 20 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

otherwise do not have access to a plan.

55

In addition, for those with

employer-sponsored plans, the Pension Protection Act of 2006 included

provisions that made it easier for certain DC plan sponsors to implement

automatic enrollment and automatic escalation so that workers can be

defaulted into plan participation with rising contributions over time.

56

Default investment arrangements, including target date funds which

invest according to length of time until retirement, can also help

participants to maintain a balanced investment portfolio with a level of risk

that is appropriate to their retirement dates. Moreover, to provide greater

assurance that individuals with DC plans will not outlive their savings,

some plan sponsors are adding an annuity option at retirement.

57

In

addition, Internal Revenue Service (IRS) regulations that went into effect

in July 2014 allow for a Qualified Longevity Annuity Contract whereby

participants in 401(k) and other qualified DC plans and traditional IRAs

may use a portion of their accounts to purchase annuities that begin

payout no later than age 85.

58

In sum, despite the efforts by the federal government, plan sponsors, and

others to encourage greater retirement savings, many individuals may not

be adequately prepared for retirement. The trend toward increasing life

55

GAO-15-556.

56

Pub. L. No. 109-280, 120 Stat. 780. Among other things, the Act exempted “automatic

contribution arrangements” that meet certain criteria from ERISA nondiscrimination testing

requirements. The Act also provided for qualifying automatic contribution arrangements to

receive protection from fiduciary liability for their default investments, if they meet certain

notice requirements and other conditions established by the U.S. Department of Labor.

See 29 C.F.R. § 2550.404c-5. In addition, in September 2009, the U.S. Department of the

Treasury announced IRS actions designed to further promote automatic enrollment and

the use of automatic escalation policies. These IRS actions included Revenue Ruling

2009-30, which demonstrates ways a 401(k) plan sponsor can include automatic

contribution increases in its plan, and Notice 2009-65, which includes sample automatic

enrollment plan language that a 401(k) plan sponsor can adopt with automatic IRS

approval.

57

Although the market remains relatively small, certain annuity contracts for retirees have

been increasing in recent years, growing by 16 percent in 2012 alone. See Variable

Annuity Guaranteed Living Benefits Utilization, 2012 Experience, A Joint Study by the

Society of Actuaries and LIMRA.

58

The regulations require that the qualified longevity annuity contract meet various

requirements, such as limitations on premiums and certain disclosure and annual

reporting requirements. The regulations also provide that the maximum age to begin

payout may be adjusted to reflect changes in mortality. 26 C.F.R. § 1.401(a)(9)-6.

Page 21 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

expectancy may mean that more individuals outlive their savings, with

only their Social Security benefits to rely on.

Lower-income individuals have shorter-than-average life expectancy,

which means that they can expect to receive Social Security retirement

benefits for substantially fewer years than higher-income individuals who

have longer-than-average life expectancy. As a result, when disparities in

life expectancy are taken into account, our analysis indicates that, on

average, projected lifetime Social Security retirement benefits are

reduced for lower-income individuals but are increased for higher-income

individuals, relative to what they would have received if they lived the

average life expectancy for their cohort.

59

Also, our analysis indicates that

one frequently suggested change to address Social Security’s financial

challenges, raising the retirement age, would further reduce projected

lifetime benefits for lower-income groups proportionally more than for

higher-income groups.

People with lower incomes can expect to live substantially fewer years as

they approach retirement than those with higher incomes, on average,

according to studies we identified and reviewed. For example, these

studies estimate that lower-income men approaching retirement live

between 3.6 and 12.7 fewer years than those in higher-income groups, on

average, depending on birth year and other factors such as whether

income groups were calculated by top or bottom half, quartile, quintile, or

decile (see table 3).

60

Similarly, studies we reviewed found that lower-

income women also live fewer years than higher-income women, on

average, with the differences ranging more widely, from 1.5 years to 13.6

59

As noted earlier, life expectancy can be expressed in two different ways: (1) as the

average number of years of life remaining for a group, or (2) as the average age at death

for a group. For simplicity, in this report, we generally use the term to mean the latter

expression (average age at death), and use the phrase “years of life remaining” when

referring to the former expression.

60

We reviewed selected longevity studies published in the past 10 years (see appendix I).

Life Expectancy

Disparities Negatively

Affect Retirement

Resources for Lower-

Income Groups

Lower-Income Groups’

Life Expectancy Has Not

Increased as Much as

Higher-Income Groups’

Life Expectancy

Page 22 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

years.

61

However, there are factors that make projecting life expectancy

for women by income more difficult than for men.

62

It is not unexpected

for life expectancy estimates to vary as they depend, among other things,

on the particular data sources, populations, and age ranges analyzed.

While the studies we reviewed found a range of life expectancy

differences by income, each of them finds that disparities exist.

63

61

The Population Health Metrics study of U.S. life expectancy, 1985-2010, that found

significant county level differences in life expectancy, by sex (described earlier in the

background), reported finding effectively “no relationship” between life expectancy and

county level per capita income. See Haidong Wang et al., 2013. However, another study

that looked at county level mortality rates in 2010 found that the lower the household

income, the higher the risk of premature death. See E.R. Cheng and D.A. Kindig,

“Disparities in Premature Mortality between High- and Low-Income U.S. Counties,”

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Mar. 28, 2012). A subsequent study by the

same authors found that mortality among women rose in 43 percent of counties over two

decades. The factors found to be most significantly associated with reductions in county

level mortality rates for both men and women were: percentage of Hispanic residents,

adults with a college degree, population density, and median household income. See

David A. Kindig and Erika R. Cheng, “Even As Mortality Fell in Most U.S. Counties,

Female Mortality Nonetheless Rose in 42.8 Percent of Counties from 1992 to 2006,”

Health Affairs, Vol 32, No 3 (March 2013).

62

According to studies we reviewed, developing life expectancy estimates for women by

income is more difficult than for men, in part because women’s income, on average,

makes up a smaller share of household income. For example, women are more likely to

work part time and earn less than men. Some studies have attempted to overcome this by

using income calculations other than individual income for women—for example, using

household income or using their spouses’ income. While these measures of income may

alleviate some challenges, some experts believe estimates of life expectancy by income

for women are still less reliable than such estimates for men. Further, it is difficult to

assess changes in women’s life expectancy by income because women’s participation in

the labor force and individual earnings have grown over the last several decades.

63

Two of the studies we reviewed calculated mortality rates rather than life expectancy.

While the results are not directly comparable, these studies found that individuals with

lower incomes have higher mortality rates and therefore shorter life expectancy than those

with higher incomes.

Page 23 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

Table 3: Selected Studies’ Projected Life Expectancy over Time for Men Approaching Retirement, by Income Group

Author (year)

Lifetime income

groupings for

comparison

(lower-income to

higher-income)

Age at which

projected life

expectancy

calculated

Projected life expectancy for

men by income gro

up:

Difference

between lower-

and higher-

income groups

Difference compared

to prior cohort (birth

cohorts compared)

Lower-

income

Higher-income

Bosworth, Burke

(2014)

Second decile to

second-highest

decile

55

80.7 years

87.1 years

6.4 years

Increased by 4 years

(between the 1920 and

1940 cohorts, for the

top and bottom

deciles)

Congressional

Budget Office

(2014)

Bottom quintile to

top quintile

a

65

89.5 years

95.7 years

6.2 years

Increased by 2.8 years

(between the 1949 and

1974 cohorts)

Cristia (2009)

Bottom quintile to

top quintile

35 to 76

n/a

n/a

3.6 years

Increased by 0.9 years

(between the 1983-

1997 and 1998-2003

periods)

Goldman, Orszag

(2014)

Bottom quartile to

top quartile

65

80.2 years

85.7 years

5.5 years

Increased by 2.4 years

(between the 1928 and

1960 cohorts)

National Academy

of Sciences (2015)

Bottom quintile to

top quintile

50

76.1 years

88.8 years

12.7 years

Increased by 7.6 years

(between the 1930 and

1960 cohorts)

Waldron (2007)

Bottom half to top

half

65

81.1 years

86.5 years

5.3 years

Increased by 4.7 years

(between 1912 and

1941 cohorts)

Source: GAO analysis of studies listed above. | GAO-16-354

Notes: This table includes studies we reviewed that estimate life expectancy by income over time for

individuals approaching retirement age (see appendix I for full list of studies we reviewed). It excludes

one study that estimates period life expectancy over time for white males and females only. Other

studies we excluded that do not estimate life expectancy over time include two studies that estimate

mortality rates, one study that estimates life expectancy for a hypothetical 1920 cohort and does not

provide information on all races together, and one study that estimates life expectancy at age 25 by

poverty threshold.

a

These estimates do not include Disability Insurance beneficiaries, who tend to have higher mortality

rates than the general population.

Moreover, disparities in life expectancy by income have grown, according

to the studies that examined trends over time (see table 3).

64

Specifically,

64

One additional study examined changes over time, but the projections were based on

period life expectancy rather than cohort estimates, so we do not include them here.

Page 24 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

all of the six studies we reviewed that examined trends over time found

growth in life expectancy differences, ranging from 0.9 to 7.6 years for

men, depending on the age, birth years, and measure of income used.

For example, a 2007 study by SSA’s Hilary Waldron found that for men

age 65 who were born in 1912, there was only a 0.7 year difference in

expected years of life remaining between top and bottom earners, but for

those born in 1941, the expected difference grew to 5.3 years (see fig.

3).

65

Similarly, for women, the studies we reviewed found differences in

life expectancy by income were greater in more recent years, and the

range in years was wider than for men. This is perhaps unsurprising, as

some analysts have noted that disparities in household income also

increased over time. According to a 2014 Congressional Budget Office

(CBO) report, between 1979 and 2011, average real after-tax earnings for

the top one percent of households grew about four times as fast as those

in the lowest fifth.

66

65

This estimate was for Social Security-covered males. Hilary Waldron, “Trends in

Mortality Differentials and Life Expectancy for Male Social Security-Covered Workers, by

Socioeconomic Status,” Social Security Bulletin, vol. 67, no. 3 (2007).

66

Congressional Budget Office, The Distribution of Household Income and Federal Taxes,

2011 (Washington, D.C.: November, 2014). See also DeNavas-Walt, Carmen, and

Proctor, Bernadette D., Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014 (Washington, D.C.:

U.S. Census Bureau, September 2015).

Page 25 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

Figure 3: Differences in Projected Years Remaining for Men, by Income Group

While higher-income groups have experienced significant growth in their

life expectancy at older ages, lower-income groups have either

experienced less growth or declines in recent decades, according to

studies we reviewed. For example, Waldron’s 2007 study projected that

65-year-old men born in 1941 with below-median earnings would live 1.3

years longer than their counterparts born in 1912, while 65-year-old men

born in 1941 with above-median earnings would live 6 years longer than

their counterparts born in 1912. Some other studies estimate that life

expectancy declined for those in the bottom of the income distribution.

For instance, a 2015 study by the National Academy of Sciences found

that life expectancy at age 50 has declined for both men and women in

Page 26 GAO-16-354 Longevity and Retirement

the bottom income quintile.

67

Specifically, men and women in the bottom

income quintile saw life expectancy decreases of 0.5 and 4 years,

respectively, when comparing the 1930 and 1960 cohorts. While the

studies we reviewed do not all agree about whether life expectancy is

decreasing or increasing slightly for the lowest earners, they all agree that

the higher-income groups are gaining more years than the lower-income

groups.

68

Some studies show that there are disparities in life expectancy by other

characteristics that have been linked with income, such as race and

education. For example, the CDC reported that the life expectancy for 65-

year-old black individuals was 1.2 years less than for their white

counterparts in 2013.

69

Other studies have also examined links with

education and found that individuals with a high school degree or less

67

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, The Growing Gap in Life

Expectancy by Income: Implications for Federal Programs and Policy Responses

(Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2015).

68

Some studies have found that higher-income individuals’ life expectancy has benefitted

most from health improvements, such as reduced smoking rates. For example, Bosworth,

Burtless, and Zhang found a significant decline in the risk of dying from cancer or heart

conditions for older Americans with above-average lifetime incomes but not for those with

below-average incomes. See Barry P. Bosworth, Gary Burtless, and Kan Zhang, Sources

of Increasing Differential Mortality among the Aged by Socioeconomic Status (Chestnut

Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, June 2015). For a related

study by these authors, see also Barry Bosworth, Gary Burtless, and Kan Zhang, Later

Retirement, Inequality in Old Age, and the Growing Gap in Longevity between Rich and

Poor (Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, Feb. 12, 2016).

69

National Center for Health Statistics, Health, United States, 2014: With Special Feature

on Adults Aged 55-64 (Hyattsville, MD: 2015). In addition, in contrast to the findings for

black individuals, according to studies we reviewed, Hispanic individuals tend to live