42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 157 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 157 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

1439

SHADOW CREDIT AND THE DEVOLUTION OF CONSUMER

CREDIT REGULATION

by

Nathalie Martin* & Lydia Pizzonia**

Shadow credit is trending. Shadow credit has all the essential attributes of

regular credit except that it is unregulated. It operates in a world in which

products and services that look, act, and feel like credit products are deemed to

be something that is not actually credit. This legal sidestep is accomplished

either by passing industry-friendly legislation or by tweaking the shadow credit

product just enough to not be defined as credit, but “something else.” That

“something else” is often called a “lease,” an “advance,” or in the case of After-

pay, simply a “service.” At its essence, however, it is still credit. More and more

shadow credit products are popping up to take the place of actual credit prod-

ucts.

The purpose of avoiding being “credit” is to avoid consumer credit regulation.

We see this trend among purveyors of rent-to-own household goods, rent-to-

own real estate, employer payday advances, buy-now-pay-later services like Af-

terpay, income sharing agreements in higher education finance, and even bail

bonds, all of which seek to avoid complying with usury laws or interest rate

caps, Article 9 of the Uniform Commercial Code (U.C.C.), the federal Truth

in Lending Act, and all other consumer credit protection laws.

While some of these products are helpful to consumers, or at least not particu-

larly harmful, some are deeply predatory. They can operate outside the law.

*

Frederick M. Hart Chair in Consumer and Clinical Law, University of New Mexico School

of Law. The author thanks Stewart Paley, Adam Levitin, Bob Lawless, and colleagues Ernesto

Longa, Joe Schremmer, George Bach, Reed Benson, Jennifer Moore, Jen Laws, and Fred Hart for

their research and comments on earlier drafts; Clair Gardner and Jarrod Greth for their fine

research assistance; and the University of New Mexico School of Law for its generous financial

assistance. The authors are also grateful to the Lewis & Clark Law Review, particularly Lead

Article Editor John Mayer, Executive Editor Alexandra Giza, Submissions Editor Colin Bradshaw,

and Editor in Chief Connor B. McDermott.

J.D. 2019, University of New Mexico School of Law. The author thanks her husband and

children for their constant encouragement and support, and Professor Kenneth Bobroff for being

a sounding board, providing insight and new ideas, and supporting her desire to initiate change

in this area.

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 157 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 157 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

1440 LEWIS & CLARK LAW REVIEW [Vol. 24.4

For example, classic rent-to-own contracts that were historically used for house-

hold goods are now being used in housing contracts in vulnerable Native

American communities.

Emerging shadow credit products are testing the limits of what should be per-

mitted in rent-to-own contracts and similar financing tools. The trend toward

shadow credit has the capacity to derail our entire consumer credit regulation

system.

I. Introduction ....................................................................................... 1441

II. The Essence of Consumer Protection and Credit Transactions ........... 1444

A. What is Shadow Credit? ................................................................ 1444

B. The Protections Consumers Need and Businesses Seek to Avoid ........ 1448

1. The Truth in Lending Act ....................................................... 1452

2. The Fair Debt Collection Practices Act ..................................... 1454

3. Other Federal Laws ................................................................ 1456

4. State Usury Laws .................................................................... 1457

C. Recourse Versus Non-recourse Debt, Article 9, and the Scope and

Legislative History of Article 9 ....................................................... 1458

1. Rent-to-Own Debt is Non-recourse Debt, but Debt Nevertheless 1458

2. The Side-Step Around Article 9 ............................................... 1459

III. The Anatomy of Rent-to-Own ........................................................... 1464

A. Rent-to-Own Fundamentals .......................................................... 1465

B. Unprecedented Self-Regulation ...................................................... 1465

C. Rent-to-Own Regulation ............................................................... 1468

1. The Substance (or Lack Thereof) of Rental Purchase Agreement

Acts ....................................................................................... 1468

2. Case Law on Rent-to-Own ...................................................... 1470

D. The Demographics of the Typical Rent-to-Own Customer ............... 1471

E. What do Customers Really Want in Rent-to-Own Transactions ....... 1472

IV. Rent-to-Own Housing and Shadow Credit ......................................... 1473

V. Rent-to-Own Housing Sheds and Native American Predation ............ 1475

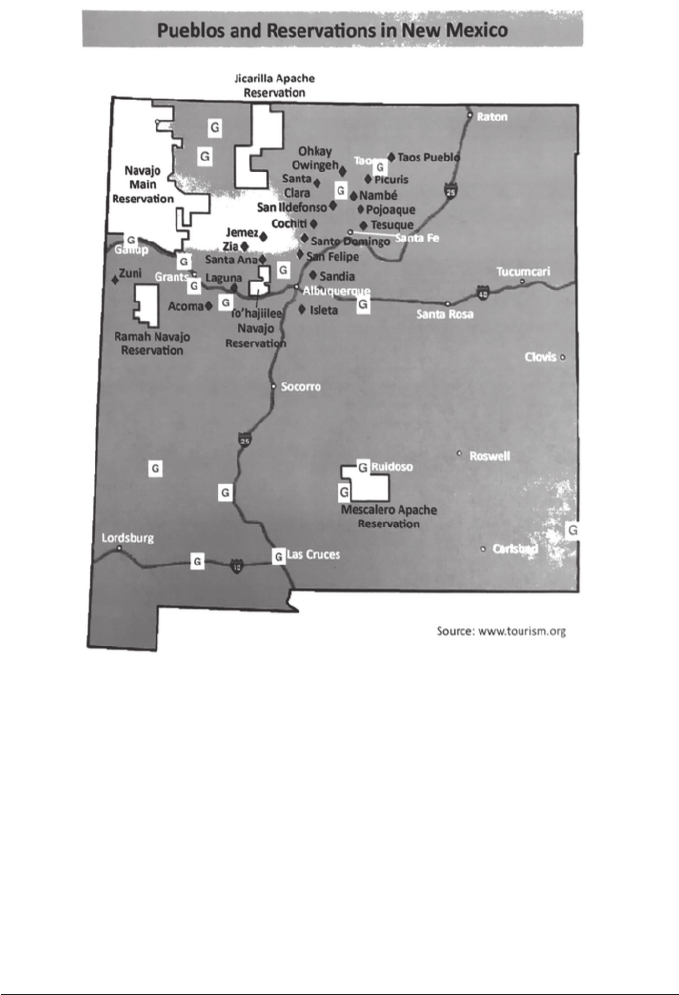

A. Native Americans are a Vulnerable Target for Rent-to-Own Shed

Deals ...........................................................................................

1476

B. Housing Crisis in Indian Country .................................................. 1477

C. Rent-to-Own Shed Dealers: The New Predator of New Mexico’s

Native Americans ......................................................................... 1479

D. An Insider’s View of Rent-to-Own Predation .................................. 1482

E. Comparing the Cost of Credit in Shed Homes to Rent-to-Own Land

Sale Contracts and Mortgages ........................................................ 1484

VI. The Greater Implications of the Credit-No Credit Distinction on the

Future of Credit Regulation ................................................................ 1484

VII. Conclusion ......................................................................................... 1487

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 158 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 158 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

2020] SHADOW CREDIT 1441

I. INTRODUCTION

As we say in the law, if it looks like a duck and it quacks like a duck it is a

duck.

1

Sometimes products in the consumer credit market look very similar to other

products, but by tweaking that product in a tiny way, a provider of credit can avoid

a great deal of regulation, including consumer protection regulation. In this Article,

we identify a dangerous trend in consumer protection law, namely the expansion of

shadow credit. Shadow credit is credit disguised as something else. Sometimes the

disguise is unintended. Other times, it is designed to avoid consumer protection

laws.

When it comes to defining what constitutes credit, what is old is suddenly new

again. If one were to find the perfect designer, Covid-19 facemask on the internet,

like my family just did, the shopper would be told to add one more thing to the

shopping cart in order to qualify for Afterpay. Afterpay is a financing service that

claims not to be financing.

2

Similarly, education finance Income-Sharing Arrange-

ments (ISAs) allow lenders to advance funds to students for tuition/living expenses

in exchange for a percentage of that student’s future income. Again, these financiers

claim not to be financers and thus not to be providing credit.

Over 50 years ago, leading up to the passage of the Truth in Lending Act

(TILA) in 1968, what counted as “credit” and was thus subject to TILA was a big

question. At the time, many states had statutorily enacted the time-price differential

doctrine.

3

Under this doctrine, if a retailer sold goods for future payment, the dif-

ferential between the price of a cash sale and that of credit sale was not interest for

usury law purposes.

4

State retail installment loan acts eventually held these fees to

be finance charges that had to be disclosed in a certain way,

5

but as we discuss in

Part III.B below, some retailers found their way around these regulations. Fifty years

later, the dance continues. Indeed, these shadow credit products are proliferating

and putting our entire consumer credit regulation system at risk.

6

1

Joe Campbell & Richard Campbell, Why Statutory Interpretation Is Done as It Is Done 11–

12 (Sydney Law School, Legal Studies Research Paper No. 14/79, 2014),

http://ssrn.com/abstract=2484315.

2

David Chan, Afterpay: Consumer Advocates Fear ‘Instant Approvals’ Will Cause Serious

Financial Hardship, ABCN

EWS (Sept. 26, 2017), https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-09-

26/afterpay-consumer-debt/8988394.

3

Adam Levitin, What Is “Credit”? Afterpay, Earnin’, and ISAs, CREDIT SLIPS (July 16, 2019,

1:31 PM),

https://www.creditslips.org/creditslips/2019/07/what-is-credit-afterpay-earnin-and-

isas.html#more.

4

Id.

5

Mourning v. Family Publ’ns Serv., Inc., 411 U.S. 356, 361(1973).

6

In his blog on the renewed importance of defining what constitutes “credit,” Adam Levitin

notes that products like payday advances, income sharing agreements for higher education finance,

and buy-now-pay-later products like Afterpay all claim not to be credit and not subject to the

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 158 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 158 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

1442 LEWIS & CLARK LAW REVIEW [Vol. 24.4

While we discuss several modern examples as evidence of the rise of shadow

credit, we focus on rent-to-own transactions to demonstrate how an entire industry

can legislate itself out of consumer credit laws and restrictions. If one industry can

accomplish this, so can others. Before we know it, our entire system of protecting

consumers could disappear. Moreover, we have identified a small segment of the

rent-to-own industry that is taking advantage of consumers, raising the question of

whether it is time to revisit the entire framework for regulating consumer credit.

We start our inquiry by asking about the nature of credit, and then whether

rent-to-own transactions are essentially credit, or just leases as the rent-to-own in-

dustry claims. The implications of this question are far-reaching. If the transaction

is essentially a sale or purchase, the transaction is a credit transaction regardless of

what you call it. In that case, the transaction is subjected to many state and federal

laws regarding disclosures, default requirements, remedies, and so on.

7

If the main

point is to rent, but never to own, that is a lease that need not be regulated as credit.

8

Long ago, the rent-to-own industry passed enabling legislation to state explic-

itly that its transactions were outside the realm of credit.

9

This legislation removes

rent-to-own transactions from all state consumer credit regulation, TILA, all other

federal regulations, and state commercial law such as Article 9 of the U.C.C.

10

This

Article explores this industry-sponsored legislation in the context of a complex set

of consumer needs. It asks whether rent-to-own contracts are indeed outside of Ar-

ticle 9 and outside all of the protections that loan products have under both state

and federal law.

11

It further asks whether we need to revisit the nature of all rent-to-

Truth in Lending Act, as well as a slew of other federal and state regulations. Levitin, supra note

3.

7

See infra Part II.A.

8

Id.

9

See infra notes 168–81 and accompanying text; see also James M. Lacko, Signe-Mary

McKernan & Manoj Hastak, Survey of Rent-to-Own Customers, F

ED. TRADE COMM’N ES-4 (April,

2000), https://www.ftc.gov/reports/survey-rent-own-customers/.

10

Id. at ES-4, 12–13.

11

Michael G. Bridge et al., Formalism, Functionalism, and Understanding the Law of Secured

Transactions, 44 M

CGILL L.J. 567, 599 (1999). As these scholars explain, from a functionalist

perspective:

a lease operates as a form of purchase money financing to the extent that it allows a lessee

who lacks the wherewithal to buy the leased goods to nonetheless obtain their possession and

use. The economic function of the transaction from the point of view of the lessor and the

purchase money secured party is similar: both obtain the right to a stream of payments dur-

ing the currency of the transaction and both can claim an in rem right to priority as against

other creditors in the event of insolvency.

Id. at 599; see also, e.g., Margaret Howard, Equipment Lessors and Secured Parties in Bankruptcy:

An Argument For Coherence, 48 W

ASH. & LEE L. REV. 253, 253–54, 279–83 (1991); John D.

Ayer, On the Vacuity of the Sale/Lease Distinction, 68 I

OWA L. REV. 667, 668, 681 (1983)

(discussing functionalist arguments in favor of the identity of leases and security).

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 159 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 159 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

2020] SHADOW CREDIT 1443

own contracts or simply find protections in situations in which the abuses seem

most egregious.

12

While our focus is rent-to-own, and ultimately a small niche market within

rent-to-own, the question of what constitutes credit has far-reaching implications

for the future of consumer credit regulation. We are watching a trend in which more

and more industries carve themselves out of the credit definition, further eroding

what consumer protection remains.

In Part II of this Article, we explore the essence of credit transactions, discuss

the goals of the consumer credit protection scheme, and examine the specific laws

through which these goals are met.

13

We then discuss the difference between re-

course and non-recourse credit and describe relevant portions of Article 9 of the

U.C.C., one of the main laws rent-to-own companies and other shadow credit pro-

viders seek to avoid.

14

In Part III, we describe the taxonomy of rent-to-own trans-

actions, how they work, how the industry regulated itself, and what these industry

regulations provide.

15

We then describe the demographics of a typical rent-to-own

customer and the goals of most rent-to-own customers in rent-to-own relation-

ships.

16

In Part IV we describe another form of the rent-to-own contract, those relating

to rent-to-own real estate.

17

We explore various predatory practices in these shadow

12

While many scholars have dabbled in rent-to-own scholarship, two have studied this

industry extensively: Professor Michael Anderson and Professor Jim Hawkins. Professor Anderson

has dedicated his career to studying rent-to-own. See, e.g., Michael H. Anderson & Raymond

Jackson, A Reconsideration of Rent-to-Own, 35

J. CONSUMER AFF. 295, 298 (2001),

http://www.thefreelibrary.com/A+Reconsideration+of+Rent-to-Own.-a080805982. Anderson

has deep ties to industry, but nevertheless is an honest scholar. In one article, he critiques a scholar

who shortens rental periods and inflates the value of rented goods in order to reduce the annual

percentage rate on typical rent-to-own transactions. Id. Professor Hawkins is a leading consumer

law scholar, who has written on many consumer products, including fertility treatment financing,

title lending, payday lending, rent-to-own, and most recently, employer payday advances. See, e.g.,

Jim Hawkins, Financing Fertility, 47 H

ARV. J. LEGIS. 115, 116 (2010) (fertility treatment

financing); Kathryn Fritzdixon, Jim Hawkins, & Paige Marta Skiba, Dude, Where’s My Car Title?:

The Law, Behavior, and Economics of Title Lending Markets, 2014 U

NIV. ILL. L. REV. 1013, 1016

(2014) (title lending); Ronald J. Mann & Jim Hawkins, Just Until Payday, 54 UCLA L. Rev. 855,

857 (2007)

(payday lending); Jim Hawkins, Renting the Good Life, 49 WM. & MARY L. REV. 2041,

2046 (2008) (rent-to-own).

Hawkins views rent-to-own from an extremely practical point of view,

expressing the desire to see the transactions as hybrids between typical credit transactions and basic

rental agreements. Id. at 2052–53. His goal is to avoid overly-paternalistic regulation in order to

maintain the rent-to-own option for consumers, and regulate with fee caps, lifetime reinstatement

polices, and other regulatory “light touches.” Id. at 2047, 2117. These are valuable contributions.

13

See infra notes 24–123 and accompanying text.

14

See infra notes 124–49 and accompanying text.

15

See infra notes 150–205 and accompanying text.

16

See infra notes 206–22 and accompanying text.

17

See infra notes 223–44 and accompanying text.

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 159 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 159 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

1444 LEWIS & CLARK LAW REVIEW [Vol. 24.4

credit transactions, sometimes called land sale contracts or contracts for deed.

18

In

Part V, we describe a recent trend that combines the classic rent-to-own contract

with the shadow housing market. More specifically, we explore predatory practices

in Native communities involving rent-to-own sheds used for housing.

19

These prac-

tices are largely unknown and thus have not been explored by previous scholars.

These rent-to-own shed transactions provide an opportunity to describe these un-

known practices and to examine the real dangers of shadow credit at its worst.

20

In Part VI, we discuss the greater implications of the credit/no credit dichot-

omy, focusing on the societal implications of sheltering shadow credit products from

regulation.

21

We provide a number of examples from other areas of the law in which

society elevates substance over form to protect various regulatory frameworks in our

complex legal system.

22

In Part VII, we conclude that the rent-to-own industry,

particularly as it morphs into areas beyond household goods, demonstrates the harm

that all shadow credit products can impart on the consumer credit regulatory sys-

tem, and perhaps even the entire credit regulatory system.

23

II. THE ESSENCE OF CONSUMER PROTECTION AND CREDIT

TRANSACTIONS

The purpose of this Part is to determine what our consumer credit regulation

system is designed to do for consumers, to which transactions it should apply, and

why. We discuss what makes a product or service “credit” as opposed to something

else. We explore why and how our legal system regulates consumer credit products

and briefly review some of the most important federal and state consumer credit

laws. We then describe the distinction between recourse and non-recourse credit,

which relates to the rent-to-own industry’s argument that rent-to-own contracts are

not credit because customers can terminate the contracts at any time without owing

more debt. We end with a Section describing Article 9 of the U.C.C. and the ways

it has been amended regarding what actually constitutes credit.

A. What is Shadow Credit?

As lawyers, we are comfortable with unsettled or grey areas in the law.

24

Indeed,

18

Id.

19

See infra notes 245–95 and accompanying text.

20

Id.

21

See infra notes 296–315 and accompanying text.

22

Id.

23

See infra notes 315–18 and accompanying text.

24

Raúl Jáuregui, Rembrandt Portraits: Economic Negligence In Art Attribution, 44 UCLA L.

REV. 1947, 1959–61, 2011–12 (1997); W. Bradley Wendel, Autonomy Isn’t Everything: Some

Cautionary Notes On Mccoy v. Louisiana, 9 S

T. MARY’S J. LEGAL MAL. & ETHICS 92, 111–13

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 160 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 160 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

2020] SHADOW CREDIT 1445

interpreting gray areas of the law is one of the skills lawyers bring to society.

25

This

interpretive process is also what makes our work interesting, more art than science.

26

Gray areas can either arise from the world at large or be created by law and lawyers

themselves, but however they arise, the law aspires to elevate substance over form

and to recognize reality rather than contort it.

27

Shadow credit operates much like regular credit but differs in small ways.

28

Shadow credit operates in the grey areas or shadows of the finance industry. When

we charge an item on a credit card, or take out a mortgage or a payday loan, we

know we are entering into a credit relationship.

29

Since creditors tend to have more

power in credit relationships than borrowers, a host of laws protect borrowers, par-

ticularly consumer borrowers.

30

What makes something credit? Starting with a basic dictionary definition,

credit is “the provision of money, goods, or services with the expectation of future

payment.”

31

Under this definition, credit is borrowing money and promising to pay

it back at a later time. Credit is a service, not a good,

32

and as Ayn Rand once pro-

claimed, credit transactions include the vast majority of economic transactions in a

complex industrial society.

33

Most of us have instincts about what constitutes credit

(2018). Our own experiences with rent-to-own come from a lifetime of interacting with low-

income consumers and first-hand knowledge of their experiences with consumer credit products.

Our experiences with actual consumers allow us to see not just the law, though that is critically

important, but also the effect of the law on human beings. Some of our reactions come from a gut

reaction, developed over three decades of teaching, writing, and law practice, about what does and

does not constitute credit.

25

Jáuregui, supra note 24, at 1963, 1986–87, 1990.

26

Id. at 1958–59, 1963, 1990, 2012.

27

See, e.g., Frank Lyon Co. v. United States, 435 U.S. 561, 581–82 (1978) (the Supreme

Court held that the title owner that acquired depreciable real estate, rather than a mere conduit

or agent, had the legal right to take tax deductions associated with depreciation on the building).

28

By shadow credit, we do not mean “shadow banking,” a phrase used during the Great

Recession of 2008 to mean activities that involved high-risk financing outside that provided by

traditional banks. See Stijn Claessens & Lev Ratnovski, What Is Shadow Banking? 3 (International

Monetary Fund, Working Paper No. 14/25, 2015), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2559504.

29

Elizabeth Renuart & Diane E. Thompson, The Truth, The Whole Truth, and Nothing but

the Truth: Fulfilling the Promise of Truth in Lending, 25 Y

ALE J. REG. 181, 184–85 (2008).

30

Id. at 185, 196–97; see also Anderson & Jackson, supra note 12, at 305 (describing rent-

to-own transactions and stating that “[d]ue to asymmetry in experience and depth of information,

the salesperson is at an advantage to the ordinary consumer regarding not only the product but

also, even more importantly, the legal and financial provisions of the contract.”).

31

Credit, MERRIAM-WEBSTER, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/credit (last

visited Dec. 20, 2020).

32

Alexei Alexandrov, Daniel Grodzicki & Özlem Bedre-Defolie, Consumer Demand for

Credit Card Services 2 (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Office of Research, Working Paper

No. 2018-03, 2018), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3135421.

33

AYN RAND, THE VIRTUE OF SELFISHNESS: A NEW CONCEPT OF EGOISM 111 (1961).

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 160 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 160 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

1446 LEWIS & CLARK LAW REVIEW [Vol. 24.4

as opposed to something else. Some of the less tangible attributes of credit include

transactions that get reported on a credit report,

34

transactions in which the con-

sumer puts down a deposit, transactions in which the item being paid for can be

repossessed, and so on. None of these attributes are determinative, however.

Federal consumer credit regulations contain numerous technical definitions of

credit. We discuss the substance of these laws later, but under Regulation Z,

35

which

regulates most consumer credit transactions including home mortgages, home eq-

uity lines of credit, reverse mortgages, credit cards, installment loans, and certain

kinds of student loans,

36

credit means “the right to defer payment of debt or to incur

debt and defer its payment.”

37

The Consumer Financial Protection Act of 2010

(CFPA), that created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, defines credit as

“the right granted by a person to a consumer to defer payment of a debt, incur debt

and defer its payment, or purchase property or services and defer payment for such

purchase.”

38

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) and the Fair Credit Re-

porting Act (FCRA) track this CFPA definition,

39

except that ECOA and the FCRA

limit a “creditor under these Acts to those who regularly extend credit, not those do

so only occasionally.”

40

The Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA) lacks a

definition of credit but broadly defines a creditor as “any person who offers or ex-

tends credit creating a debt or to whom debt is owed.”

41

Debt is defined by the Fair

Debt Collection Practices Act as:

any obligation or alleged obligation of a consumer to pay money arising out

of a transaction in which the money, property, insurance, or services which

are the subject of the transaction are primarily for personal, family, or house-

34

Alexandra P. Everhart Sickler, The (Un)Fair Credit Reporting Act, 28 LOY. CONSUMER L.

R

EV. 238, 243 n.21 (2016).

35

Regulation Z, 12 C.F.R. § 1026.1 (2019).

36

Id.

37

Id. at § 1026.2(a)(14); see also Levitin, supra note 3. Regulation Z, section 1026.2(b)(3)

also states that “[u]nless defined in this part, opportunity words used have the meanings given to

them by state law or contract.” This means more transactions might fall within TILA/Reg Z than

it appears at first glance. Levitin, supra note 3.

38

Consumer Financial Protection Act (CFPA) of 2010 § 1002, 12 U.S.C. § 5481(7) (2018)

(definitions). Oddly, there is no definition of debt. Id.

39

Under ECOA, credit is defined as, “the right granted by a creditor to a debtor to defer

payment of debt or to incur debts and defer its payment or to purchase property or services and

defer payment therefor.” Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA), 15 U.S.C. § 1691a(d) (2018);

Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), 15 U.S.C. § 1681a (r)(5) (2018) (defining “credit” and

“creditor” as having the same meaning as in the ECOA).

40

Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) §§ 1692(a)–(e); see also Fair Credit Reporting Act

(FCRA) § 1681a(r)(5).

41

Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA), 15 U.S.C. § 1692a(4) (2018).

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 161 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 161 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

2020] SHADOW CREDIT 1447

hold purposes, whether or not such obligation has been reduced to judg-

ment.

42

While TILA’s definition of “credit” is similar to that of the CFPA and

ECOA/FCRA, providing that “the right granted by a creditor to a debtor to defer pay-

ment of debt or to incur debt and defer its payment,”

43

its definition of “creditor” is

entirely different:

The term ‘creditor’ refers only to a person who both (1) regularly extends,

whether in connection with loans, sales of property or services, or otherwise,

consumer credit which is payable by agreement in more than four installments

or for which the payment of a finance charge is or may be required, and (2) is

the person to whom the debt arising from the consumer credit transaction is

initially payable on the face of the evidence of indebtedness or, if there is no

such evidence of indebtedness, by agreement.

44

In describing all of these various definitions of debt and credit, Professor Adam

Levitin explains:

Credit is generally defined as the right to defer payment of an obligation. But

sometimes it has to be granted by a “creditor,” and “creditor” is defined sub-

stantially differently by statute. In particular, TILA requires either a possible

finance charge or payment in more than four installments.

45

Needless to say, much of this language is in conflict, even though many of these

federal laws apply to the same transaction.

When it comes to rent-to-own, many consumer law scholars and legislators

instinctively believe that rent-to-own transactions are credit transactions.

46

In his

discussion of whether rent-to-own is regulated by the Consumer Financial Protec-

tion Bureau, Jim Hawkins catalogues a list of congresspersons who assumed rent-

to-own was credit.

47

Many consumers also assume they are using credit to buy some-

thing when they enter into rent-to-own transactions, because they are not paying

42

Id. at § 1692b(5).

43

Truth in Lending Act (TILA), 15 U.S.C. § 1602(f) (2018).

44

Id. at § 1602(g).

45

Levitin, supra note 3.

46

Jim Hawkins, The Federal Government in the Fringe Economy, 15 CHAPMAN L. REV. 23,

31–32 (2011).

47

“For instance, consider this exchange between Senators Dodd and Schumer when

discussing the differences between the bill the House and Senate passed:

DODD: Could we try, I’m not going to—as I said I’m not going to offer the amendment

now but could we try to deal with the non-bank payday lenders and the non-bank rent to

own type people who escape regulation here?

DODD: Well, we’ve raised that with the other side . . .

SCHUMER: The House put it in. No, the House is OK with it. The House has it in their

bill.

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 161 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 161 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

1448 LEWIS & CLARK LAW REVIEW [Vol. 24.4

the full price at the moment of the purchase.

48

Even atypical rent-to-own customers

often assume that rent-to-own is credit.

49

So why aren’t rent-to-own transactions

credit? Primarily because the industry passed laws proclaiming that rent-to-own was

not “credit,”

50

as described in Part III.B below.

B. The Protections Consumers Need and Businesses Seek to Avoid

The point of being “not credit” is to avoid consumer credit regulation, but why

do we regulate consumer credit in the first place? Concerns include high fees, dis-

guised fees, repossession without notice, unfair default provisions, and unequal bar-

gaining power.

51

Consumer protection laws come in two types: disclosures and substantive reg-

ulations.

52

Various federal and state laws protect consumers from harm, including

inaccurate, misleading, or deceptive practices engaged in to gain an advantage over

consumers.

53

The policy behind disclosure is that consumers are less sophisticated

than businesspeople, but that if sufficient information is provided to consumers,

Testimony from people supporting the Military Lending Act (MLA) also assumes rent-to-own is

credit. In support of an amendment to the MLA, Senator Jack Reed stated:

Rent-to-own loans. This is where you go to a shop and you say I would like to rent a TV for

30 days because you am [sic] deploying in 45 days . . . then you don’t deploy so you keep it,

and in some cases, you end up paying two to three times the retail price of the appliance. At

least individual soldiers have to be informed of those practices and know about it. We have

to be sure they are getting that information . . . . That is what we want to do – coordinate

these activities through a military liaison at a consumer financial protection agency. We want

to do that because it is the right thing to do and because if we cannot protect the men and

women who are protecting us, then we have to ask seriously whether we are doing our job. I

know they are doing their job.

Id. at 30–31.

48

Lacko, supra note 9, at ES-4.

49

One friend, a law professor, was renting a piano and it ultimately was taken back by its

owner. She sought Professor Martin’s advice as a consumer. She assumed that once she had paid

the fair market value of the sued piano, she would own it. This was without any additional interest

or fees.

50

See infra notes 168–81 and accompanying text.

51

Lacko, supra note 9, at 3.

52

According to scholar Scott Burnham, consumer law serves three primary functions: “(1)

the disclosure function to provide consumers with essential information, (2) the representation

function to act as the bargaining agent for the consumer by mandating substantive provisions

consumers would otherwise be unable to obtain, and (3) the bargaining function to offer

consumers a choice.” Scott J. Burnham, The Regulation of Rent-to-Own Transactions, 3 L

OY.

CONSUMER L. REV. 40, 41 (1991).

53

Federal Trade Commission Act (FTCA), 15 U.S.C. §§ 41–77 (2019) (prohibiting “unfair

methods of competition and unfair or deceptive acts or practices”); Truth-in-Lending Act (TILA),

15 U.S.C. § 1602(a) (2018) (having among its goals to protect consumers against inaccurate and

unfair billing).

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 162 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 162 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

2020] SHADOW CREDIT 1449

this can help level the playing field.

54

We also want to ensure that consumers have

a way to compare the cost of credit being offered by various credit service provid-

ers.

55

Disclosure can be appealing because, theoretically, it encourages consumers to

be free agents and limits paternalism.

56

If it works, and consumers can read and

understand the disclosures, the disclosures can help market forces operate more ef-

ficiently.

57

In contrast, substantive protective regulation limits free choice, including the

choice to make bad decisions. Even if substantive regulation does limit free will,

where bargaining power is imbalanced, substantive regulation may be necessary to

achieve fairness.

58

In reality, substantive versus disclosure regulation is a false di-

chotomy because disclosures are critical to enforcing substantive regulations and be-

cause most consumer protection laws contain both.

The rent-to-own industry has been clear in its desire to avoid most consumer

credit regulation schemes. In describing the development of the industry, James

Nehf explains:

Eventually, entrepreneurs noticed an apparent void in consumer credit laws.

When read literally, many statutes applied only to transactions in which a

“debt” was created and the consumer was obligated to pay for the full value

of the goods. They did not cover a transaction in which the consumer was

obligated for only a week or two and then had the option of renewing the

agreement for a number of successive weeks or months in order to complete

the contract. By 1960, businesses had opened in low-income neighborhoods

offering short-term renewable leases, with no credit check, that promised im-

mediate possession of furniture and home appliances. Moreover, a consumer

renewing the lease long enough would obtain ownership of those goods. The

contract was thus styled not as a sale of goods on credit but as a weekly or

monthly lease that ultimately would lead to a transfer of ownership if the cus-

tomer continued leasing for a stated period, usually twelve or eighteen

months. A market for the [rent-to-own] service was quickly established.

59

If a product is not debt or credit, it escapes compliance with TILA,

60

the

54

Susan Lorde Martin & Nancy White Huckins, Consumer Advocates vs. the Rent-To-Own

Industry: Reaching a Reasonable Accommodation, 34 A

M. BUS. L.J. 385, 388 (1997).

55

Renuart & Thompson, supra note 29, at 184, 187.

56

Hawkins, supra note 12, at 2115.

57

Id. at 2116.

58

Id. at 2092–93; see also New Mexico ex rel. King v. B & B Inv. Grp., Inc., 329 P.3d 658,

669–70 (N.M. 2014) (decision of the New Mexico Supreme Court discussing substantive and

procedural unconscionability).

59

James P. Nehf, Effective Regulation of Rent-to-Own Contracts, 52 OHIO ST. L.J. 751, 755

(1991).

60

Truth-in-Lending Act (TILA), 15 U.S.C. §§ 1601–1667f (2018).

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 162 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 162 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

1450 LEWIS & CLARK LAW REVIEW [Vol. 24.4

FDCPA,

61

and numerous other federal and state laws applicable to the extension of

credit.

Some of the products in the marketplace that currently claim to not be credit

include rent-to-own contracts,

62

bail bonds,

63

employer loans,

64

buy-now-pay-later

services like Afterpay and education finance ISAs. These last two are modern cut-

ting-edge examples of the expansion of shadow credit.

Afterpay works with retailers to provide financing for relatively small purchases,

by breaking up the purchase price into four equal installments.

65

In the same breath,

Afterpay claims that “[u]nlike some typical finance businesses, Afterpay relies on

and only benefits from customers not going into default, paying off their orders in

full and on time,” but also that “[a]fterpay charges a flat $10 late fee per payment

and a further late fee of $7 if the payment is not made within 7 days.”

66

On a small

purchase, these fees represent thousands of percentage points per annum if stated as

interest rates. The first YouTube video to pop up to help consumers understand

Afterpay calls this service interest-free, which is scary.

67

The capacity to use essen-

tially unregulated services like this to overspend is breathtaking, especially for

younger consumers.

68

Likewise, with education finance ISAs, lenders advance funds to the consumer

61

Id. § 1692a.

62

Hawkins, supra note 12, at 2051.

63

California felt the need to clarify that bail bonds are indeed credit after the industry

claimed they were not and thus claimed they did not need to state an APR in their contracts. S.

318, 2019-20 Leg., Reg. Sess. (Cal. 2019).

64

Jim Hawkins, Earned Wage Access and the End of Payday Lending, B.U. L. REV.

(forthcoming 2020) (manuscript at 36–41), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3514856.

65

Afterpay Fact Sheet, AFTERPAY, https://www.afterpay.com/attachment/44/show (last

visited Dec. 21, 2020).

66

Id.

67

Destinyc06, What is afterpay??? Afterpay pros and cons!! How to use afterpay., YOUTUBE

(Mar. 23, 2019), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GFw1-klb7-s.

68

As Levitin explains in his blog:

This finance charge or four-installments provision is key for buy-now-pay-later products like

Afterpay. Afterpay allows the consumer to purchase goods now and pay over 4 equal install-

ment payments. So it’s within the 4-installment part of the “creditor” definition. And After-

pay does not have a charge if you pay on time. It only has a late fee. Late fees are excluded

from the finance charge if it is for “actual, unanticipated late payment.” So if borrowers are

anticipated to pay off the Afterpay advance within the four installments, no problem—no

finance charge, and not a “creditor” for TILA, and therefore not subject to TILA disclosure

rules, TILA error resolution rules, or TILA unauthorized transaction liability limitation

rules. Of course, if most consumers are paying late, then Afterpay’s late fee would be a finance

charge, so it would be a creditor, extending credit and subject to TILA. (I have no reason to

believe that this is the case).

Levitin, supra note 3. Note, however, that even though Afterpay is not subject to TILA, it is still

subject to ECOA, FCRA, FDCPA, and CFPA.

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 163 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 163 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

2020] SHADOW CREDIT 1451

for tuition/living expenses in exchange for the consumer’s promise to pay a percent-

age of his or her future income, over and above a minimum amount, to the lender.

69

While the total number of payments, payment time, and/or amount of payment

may be capped, generally speaking, “the more you earn, the more you pay.”

70

While these ISAs are clearly used to finance an education, they claim to be “not

credit.”

71

Similar to buy-now-pay-later arrangements like Afterpay, and like

Paycheck advances, the financiers claim that they do not issue credit.

72

Like the

rent-to-own industry, ISA providers claim that only unconditional promises to re-

pay constitute credit,

73

belying the existence of non-recourse credit. Indeed, in one

law firm’s analysis of ISAs, the firm explains in detail, law by law, why all of the

usual consumer protection laws do not apply to ISAs.

74

We can see that many cred-

itors would indeed want “more of that please.” Below we describe some of the laws

these entities seek to avoid.

69

Levitin, supra note 3.

70

Id.; see also Robert Farrington, Be Careful with Income Sharing Agreement (ISAs) to Pay for

College, F

ORBES (Apr. 12, 2019), https://www.forbes.com/sites/robertfarrington/2019/04/

12/income-sharing-agreements-to-pay-for-college/#70fc4d1052e0.

71

Levitin describes them as more like “participating preferred shares, in that if there’s

enough to pay the common equity (the consumer) a dividend, then the preferred shares must be

paid a dividend. While we often call preferred shares equity, they’re really a hybrid of equity and

debt features.” Levitin, supra note 3.

72

Regulatory Treatment of Educational ISAs Under Federal and Select State Consumer Credit

Statutes, M

ORRISON & FOERSTER LLP (Mar. 2019), https://media2.mofo.com/documents/

190408-regulatory-educational-consumer-credit-statutes.pdf.

73

Id. at 1–2. As Levitin explains in his blog:

Whether ISAs are credit is critical to their viability. ISAs are priced differently depending on

school and/or major. A computer science major is likely to have to pay a lower percentage

than an anthropology major. One might imagine a pricing differential between students at

an HBCU or minority-serving institution and at other schools. If ISAs are credit for ECOA

purposes, there’s likely, therefore, to be major disparate impact issues.

. . .

For CFPA purposes, there are two possible ways [ISAs could be credit]. First, for ISAs pro-

vided by the school itself (such as Perdue University), the answer is clearly yes. “Credit” is

“the right granted by a person to a consumer to . . . purchase . . . services [education] and

defer payment for such purchase.” If a school is the ISA provider, it’s definitely credit for the

CFPA, which means UDAAP prohibitions apply. I think the answer is also the same if the

provider is affiliated with the school, as the CFPA has an anti-evasion provision in its defi-

nition of “financial product or service”.

Second, for ISAs provided by third-parties, the question is whether the ISA is a “right granted

by a person to a consumer to defer payment of a debt” or to “incur debt and defer its pay-

ment.” (To be sure, the language about “purchase property or services and defer payment for

such purchase” does not necessarily refer to a purchase from the person . . .).

Levitin, supra note 3.

74

MORRISON & FOERSTER LLP, supra note 72, at 2, 6–21.

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 163 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 163 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

1452 LEWIS & CLARK LAW REVIEW [Vol. 24.4

1. The Truth in Lending Act

The granddaddy of all consumer protection laws is TILA,

passed by Congress

in 1968.

75

TILA requires all credit providers to disclose all fees and charges in one

number, an annual percentage rate (APR) comprised of the sum of the amount fi-

nanced and the finance charge, as well as the number, amount, and due dates of all

scheduled payments and the amount of any late payment charge.

76

Congress’ pur-

pose in enacting TILA was to allow consumers to more readily compare the various

credit terms available, to avoid the uninformed use of credit, and to protect the

consumer against “inaccurate and unfair credit . . . practices.”

77

As explained by

Elizabeth Renuart and Diane Thompson:

The drafters of TILA understood that without uniform disclosure, interest

calculations are forbiddingly complex. The APR is meant to be a simplifying

heuristic that allows borrowers to decide between options that are otherwise

overwhelmingly complex. Many consumers stumble when confronted with

even basic computational problems. Lenders can compound those missteps

through marketing that distracts consumers from the salient points.

78

Congress designed the APR to be the single number for consumers to focus on

when shopping for credit, and thus the APR has become the touchpoint for con-

sumers comparing the cost of credit.

79

The purpose of TILA is to allow consumers

to compare fees, or the total cost of goods or housing, by comparing the annual

percentage rate on credit costs.

80

Moreover, TILA has been remarkably effective at

getting consumers to pay attention to interest rates and the cost of credit.

81

TILA’s

familiar and tidy TILA text box makes easy an otherwise daunting math task.

82

TILA applies to credit sales, which include “any contract in the form of a bail-

ment or lease in which the bailee or lessee contracts to pay a sum substantially equiv-

alent to or in excess of the aggregate value of the property and services involved and

the bailee or lessee will become, or for no other or a nominal consideration has the

option to become, the owner of the property upon full compliance with his obliga-

tions under the contract.”

83

Barring industry legislation to the contrary, this lan-

guage certainly covers rent-to-own transactions.

75

Truth in Lending Act (TILA), Pub. L. No. 90-321, 82 Stat. 146 (1968) (current version

at 15 U.S.C. § 1601 (2018)).

76

Id. at § 1638(a)(6).

77

Id. at § 1601(a); see also Martin & Huckins, supra note 54, at 388–89.

78

Renuart & Thompson, supra note 29, at 190.

79

Id. at 217.

80

Id. at 190.

81

Id. at 189–90.

82

Id.

83

Martin & Huckins, supra note 54, at 389; Truth in Lending Act (TILA), 15 U.S.C. §

1602(g) (2018).

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 164 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 164 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

2020] SHADOW CREDIT 1453

Retail sales stores like Conn’s or Best Buy, who sell items on credit, must com-

ply with TILA, but rent-to-own stores in states with industry-sponsored legislation

do not. Yet there is no doubt that the market substitute for rent-to-own contracts

are installment sales contracts offered through retailers like Conn’s. Conn’s is a na-

tional appliance, furniture, and electronic store which makes most of its sales from

the credit it offers to consumers who have difficulty getting credit elsewhere.

84

It is

required to include an APR in all its contracts which puts it at a disadvantage com-

pared to rent-to-own companies.

To help consumers compare the cost of their goods and credit services to those

offered by typical rent-to-own companies, Conn’s offers a side-by-side comparison

on their web site.

85

For an LG 43” television, their cash price is $699.99 and their

financed price over 24 months is $1,173.52. They compare this to a typical rent-to-

own transaction for the same television in which the cash price is $1,046.05 and the

financed price is $2,092.09.

86

The point of all this is not the exorbitant cost, but the fact that Conn’s and

rent-to-own are not on a level playing field because Conn’s is required to be honest

and transparent in its disclosure of the total costs of its products and services and

rent-to-own is not, despite that these transactions are market substitutes.

87

84

Lawrence Meyers, A Case Study in Capital Preservation: Conn’s (Part 1), WYATT INV.

RESEARCH (Sept. 22, 2014), https://www.wyattresearch.com/article/capital-preservation/.

85

YES MONEY vs. Rent To Own, CONNS HOMEPLUS, https://www.conns.com/yes-money-

financing-vs-rent-to-own-texas, (last visited on Aug. 27, 2020).

86

Id. This is a saving of $918 over roughly two years. Id. They do the same math for an LG

French door refrigerator, which they sell for $1,699.97 cash or $2,515.12 financed. With rent-to-

own, one would pay $2,500.53 for the same refrigerator in cash or $3,846.96 financed, a $1331

savings. Finally, they offer a sofa set for $1,979.99 in cash or $2,890.96 financed, whereas these

same items would cost roughly $2,080 in cash or $4,160 over time from a rent-to-own

establishment.

87

A few courts have considered whether rent-to-own companies must disclose an APR and

comply with TILA. Some have found that rent-to-own contracts fall within TILA, given that in

substance they are the same as a credit transaction and that in most cases the customer intends to

buy the item, not merely rent it. See Clark v. Rent-It Corp., 685 F.2d 245, 248 (8th Cir. 1982);

Davis v. Colonial Sec. Corp., 541 F. Supp. 302, 305 (E.D. Pa. 1982); Waldron v. Best T.V. &

Stereo Rentals, Inc., 485 F. Supp. 718, 719 (D. Md. 1979); Murphy v. McNamara, 416 A.2d

170, 177 (Conn. Super. Ct. 1979). Most courts, however, have found that TILA does not apply

to rent-to-own contracts, on the reasoning that in a rent-to-own transaction, the customer does

not promise to pay the full value of the goods he or she is acquiring. See, e.g., Ortiz v. Rental

Mgmt., Inc., 65 F.3d 335, 342 (3d Cir. 1995); In re Hanley, 135 B.R. 311, 314 (C.D. Ill. 1990);

Clark v. Rent-It Corp., 511 F. Supp. 796, 799 (S.D. Iowa 1981); LeMay v. Stroman’s, Inc., 510

F. Supp. 921, 923 (E.D. Ark. 1981); Dodson v. Remco Enters., Inc., 504 F. Supp. 540, 543

(E.D. Va. 1980); Smith v. ABC Rental Sys. of New Orleans, Inc., 491 F. Supp. 127, 397 (E.D.

La. 1978), aff’d, 618 F.2d 397 (5th Cir. 1980); Stewart v. Remco Enters., Inc., 487 F. Supp. 361,

363 (D. Neb. 1980); Remco Enters., Inc. v. Houston, 677 P.2d 567, 573 (Kan. App. 1984).

Moreover, in 1981, the Federal Reserve Board, empowered by Congress to issue implementing

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 164 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 164 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

1454 LEWIS & CLARK LAW REVIEW [Vol. 24.4

Some scholars insist that providing an APR in rent-to-own transactions will

only confuse customers. For example, Michael Anderson claims that APRs do not

help consumers understand rent-to-own transactions and that they “neither convey

sufficient information to enable a consumer to rationally choose the most efficient

alternative nor can they be cited as evidence of exploitation of either [rent-to-own]

or laundromat customers.”

88

Similarly, Professor Jim Hawkins has argued that

APRs should not be required in rent-to-own transactions, in part because consumers

do not understand APRs and cannot calculate them,

89

and in part because the in-

dustry has indicated in the strongest possible way that if it has to disclose an APR,

it will leave the marketplace.

90

On the other hand, consumers need not be able to calculate an APR as long as

they can compare two TILA boxes, which many apparently can do.

91

APR disclo-

sures are still relevant in contracts shorter than one year in duration. After all, one

need not travel a mile to go a certain number of miles per hour. If rent-to-own

dealers were required to disclose the APR, this interest rate might shock consumers

into reconsidering signing on the dotted line. Then, on the other hand, it may not,

but at least consumers could compare the cost of a rent-to-own transaction to an

installment purchase agreement if they wanted to.

2. The Fair Debt Collection Practices Act

The FDCPA sets limits on the ways in which debt collectors can contact con-

sumers to collect a debt. For example, debt collectors may not call before 8 am or

after 9 pm,

92

call a consumer at work,

93

employ any unfair practices in an attempt

to collect a debt,

94

or conceal his or her identity on the phone.

95

Moreover, if the

consumer asks to never be contacted again, the debt collector must cease all contact

regulations for the TILA, clarified the scope of the act by amending its Regulation Z to define a

credit sale as including “a bailment or lease (unless terminable without penalty any time by the

consumer).” Martin & Huckins, supra note 54, at 389–90. Rather, he or she has an option to keep

paying and own the item at the end of a certain term. But see Perez v. Rent-a-Ctr., Inc., 892 A.2d

1255, 1257–58 (N.J. 2006).

88

As Anderson explains:

Requirements that rent-to-own agreements disclose implicit APRs merely cloud the issue for

consumers because they are not simply disguised installment contracts any more than are

layaway plans or the long-term use of coin-operated washing machines and photocopiers.

Anderson & Jackson, supra note 12 , at 304–05.

89

Hawkins, supra note 12, at 2107.

90

Id. at 2103–04.

91

See Renuart & Thomas, supra note 29, at 217–18.

92

Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA), 15 U.S.C. § 1692c (a)(1) (2018).

93

Id. § 1692c (a)(3).

94

Id. § 1692f.

95

Id. § 1692d (6).

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 165 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 165 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

2020] SHADOW CREDIT 1455

with that consumer.

96

The FDCPA also dictates how a debt collector must act when

communicating with a third party about the consumer being collected upon, and

dictates that debt collectors cannot even share information pertaining to a debt to

anyone but the consumer, a spouse, or a parent if the consumer is underage.

97

Debt

collectors cannot communicate with consumers by postcard or in any other way that

invades privacy about the debt, nor can they publish any kind of listing of consumers

that have not paid a debt, except to a consumer bureau.

98

If a consumer hires an attorney and tells the debt collector he or she is repre-

sented, the debt collector can no longer communicate with the consumer directly.

99

Debt collectors are prohibited from using any form of harassment or abuse while

attempting to collect.

100

They cannot lie or falsely imply that the consumer has

committed a crime.

101

While these rules do not generally apply to companies col-

lecting on their own debts, if the creditor collects under a slightly different name

than the one they otherwise operate under, the FDCPA rules do apply.

102

If the

FDCPA is violated, the consumer can recover statutory and actual damages plus

attorney’s fees, an important remedy when seeking a lawyer.

103

The FDCPA does not apparently apply to rent-to-own transactions, yet fair

debt collection in rent-to-own transactions is a problem. According to the National

Consumer Law Center (NCLC), the rent-to-own industry has used the threat of

arrest and criminal sanctions to obtain payments from customers.

104

In many states,

if a customer misses a single payment and does not promptly return the merchan-

dise, the rent-to-own dealers pursue criminal charges against the customer.

105

The

industry, enabled by state criminal statutes and prosecutors’ offices, has pursed crim-

inal theft charges against renters of property, which the NCLC likens to the resur-

gence of debtor’s prison and the criminalization of poverty.

106

In other consumer

transactions, failure to make a payment would be considered a breach of contract, a

civil matter, but, because in rent-to-own contracts, the dealers retain title to the

property, dealers base their criminal claims on “theft of services” or “theft of rental

96

Id. § 1692c (c).

97

Id. §§ 1692c (b), (d).

98

Id. §§ 1692b (4)–(5), 1692d (d), 1692f (7).

99

Id. §§ 1692b (6), 1692c (a)(2).

100

Id. § 1692d.

101

Id. §§ 1692e (7)–(8), (10).

102

Id. § 1692a (6).

103

Id. § 1692k (a).

104

Brian Highsmith & Margot Saunders, The Rent-To-Own Racket: Using Criminal Courts

to Coerce Payments from Vulnerable Families, N

AT’L CONSUMER L. CTR. 2 (Feb. 2019),

https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/criminal-justice/report-rent-to-own-racket.pdf.

105

Id. at 3.

106

Id. at 4. In these situations, dealers use intimidation tactics on customers struggling to

make payments on their rent-to-own contracts. Id. at 3, 9.

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 165 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 165 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

1456 LEWIS & CLARK LAW REVIEW [Vol. 24.4

property.”

107

NCLC attorneys also describe how state agencies such as prosecutors’ offices

and the police are being used by the rent-to-own dealers.

108

State theft laws vary

widely. Some explicitly apply to rent-to-own contracts, while others are silent on

whether they apply to rent-to-own transactions.

109

Some state statutes base the se-

verity of the offense on the value of the property (i.e., misdemeanor versus felony)

and are particularly concerning because of the high mark-up on the property being

rented in these contracts.

110

For example, someone arrested for theft of a TV worth

$200 at retail might be charged with stealing property worth $1200 if that’s what

the inflated “cash price” of the TV is in the rent-to-own agreement.

111

Thus a simple

failure to pay a consumer debt, a civil collection suit, becomes first a criminal mis-

demeanor charge that can then be inflated to a felony conviction which carries all

of the consequences of serious criminal behavior, including inability to vote, obtain

employment, etc.

3. Other Federal Laws

The Consumer Leasing Act, enacted by Congress in 1976, applies to consumer

leases that obligate the consumer for more than four months.

112

The Act requires

lessors to disclose the initial payment, any official fees or other incidental charges,

and the number, amount, total amount, and due dates of the periodic payments,

but does not require the disclosure of a finance charge or an annual percentage rate

107

Id. at 3. Only three states specifically exclude RTO transactions from their theft statutes:

Connecticut, South Carolina, and Virginia. Id. at 12.

108

Id. at 11.

109

Id. at 12.

110

Id. at 13.

111

Advocates suggest that state laws be passed to protect consumers from being targeted by

rent-to-own dealers. Some suggested provisions explicitly excluding rent-to-own contracts from

theft statutes, requiring specific proof that the defendant intended to steal the property,

establishing a civil legal process through which rent-to-own deals and consumers can resolves

disputes, and regulating coercive collection strategies by imposing legal liability for threatening

arrest with no reasonable basis. Id. at 3; see also Shannon Najmabadi & Jay Root, New Texas Law

Protects Rent-to-own Customers Against Criminal Prosecution, T

EXAS TRIBUNE (June 21, 2019, 9:00

AM), https://www.texastribune.org/2019/06/21/new-texas-law-protects-rent-own-customers-

against-criminal-prosecution/ (describing the passage of this kind of state law). There is also the

FCRA, but this act is used by creditors and non-creditors alike. KaydenPhoenix2011, Credit

Advice, CREDIT KARMA (May 19, 2011), https://www.creditkarma.com/question/does-leasing-

furniture-and-other-items-help-boost-a-credit-score/. Rent-to-own establishments send mixed

signals on whether they do or do not report credit, but one thing is clear: if they do not, that does

not help one’s credit, and taking out a regular loan does. Ciaran John, Does Rent to Own Help

Your Credit?, T

HE NEST, https://budgeting.thenest.com/rent-own-credit-23222.html (last visited

Oct. 21, 2020).

112

Truth in Lending Act (TILA), 15 U.S.C. § 1667 (1) (2018).

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 166 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 166 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

2020] SHADOW CREDIT 1457

because the lessor is not extending credit.

113

These requirements are extremely min-

imal,

114

yet the rent-to-own industry need not even comply with these laws because

rent-to-own contracts do not obligate the consumer beyond the one week or one

month rental.

The ECOA prohibits a creditor from discriminating against an applicant on

the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, marital status, age, or receipt

of public assistance.

115

Since rent-to-own deals are allegedly not credit, rent-to-own

dealers are allowed to discriminate. The FCPA requires those who collect payments

on debts to report on such activity in a fair and accurate manner,

116

but these re-

quirements do not apply of course if rent-to-own transactions do not involve the

extension of credit.

117

4. State Usury Laws

Another set of laws that rent-to-own dealers seek to avoid is usury laws, or laws

that cap the interest rates that a lender can charge on loans.

118

To establish a usury

claim at common law, a plaintiff must ordinarily prove the following: (i) a loan of

money or forbearance of debt, (ii) an agreement that the principal shall be repayable

absolutely, (iii) the exaction of a greater amount of interest than is allowed by law,

and (iv) an intention to evade the law at the inception of the transaction.

119

Sixteen states plus the District of Columbia have usury caps ranging from 12%

113

Id. at § 1667a (9).

114

See Martin & Huckins, supra note 54, at 391 n.42, stating that:

The industry has recognized that because the provisions of the Consumer Leasing Act are so

“benign,” some RTO dealers might attempt to conform their agreements to its requirements.

Ed Winn III, Looking at Leasing, PROGRESSIVE RENTALS, Dec. 1994/Jan. 1995, at 10.

Legal counsel to the Association of Progressive Rental Organizations, a RTO trade group,

advises caution to dealers considering such action for the following reasons: 1) advertising

“no obligation,” a particular attraction of RTO, might subject them to charges of false ad-

vertising; 2) RTO customers are quite likely to return the merchandise during the initial

four-month rental period; if dealers, to avoid expenses, do not take default judgments, they

may be viewed as not really being in the leasing business, but they would no longer be in

compliance with state RTO statutes; 3) the availability of a purchase option becomes an issue

because, if one is offered, it has to be for a price greater then [sic] “nominal” or the transaction

may be characterized as a sale, subjecting the transaction to the TILA and state installment

sales statutes.

Id. at 12–13; FED. DEPOSIT INS. CORP., CONSUMER COMPLIANCE EXAMINATION MANUAL V-7.1

(Sep. 2015), https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/compliance/manual/5/v-7.1.pdf.

115

Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA), 15 U.S.C. § 1691 (2018).

116

Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), 15 U.S.C. § 1681(a) (2018).

117

Rent-to-own agencies surely use the credit reporting system to check on customer’s

creditworthiness, so they are using the system and they should also report to it.

118

Miller v. Colortyme, Inc., 518 N.W.2d 544, 549–50 (Minn. 1994).

119

Id. at 549.

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 166 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 166 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

1458 LEWIS & CLARK LAW REVIEW [Vol. 24.4

to 36% per annum. Minnesota is one of those states.

120

As a result, in Miller v.

Colortyme, the Minnesota Supreme Court had to decide if a rent-to-own transaction

was a credit transaction because if so, the transaction involved an interest rate well

above the Minnesota interest rate cap.

121

The court ultimately held that rent-to-

own transactions were credit sales and thus subject to general usury laws.

122

Naturally, being able to get out from under usury caps is a tremendous benefit

for a creditor. For example, payday lenders, which charge 300% per annum or more,

cannot operate in states with usury caps.

123

If rent-to-own transactions are not

credit, they need not comply with usury laws and can charge whatever they want.

C. Recourse Versus Non-recourse Debt, Article 9, and the Scope and Legislative

History of Article 9

Secured debt comes in two types: recourse debt, in which the creditor can pur-

sue the debtor for the full amount even if the collateral doesn’t cover it, and non-

recourse debt, where the creditor can only realize on the collateral for the debt, once

the debtor stops paying.

124

Article 9 covers all security interests, whether the debt is

recourse or non-recourse.

125

Several industries that look like they are providing se-

cured credit are claiming that their products are not credit at all but something else.

This Section describes these different types of secured credit and why we care if a

vendor is providing secured credit.

1. Rent-to-Own Debt is Non-recourse Debt, but Debt Nevertheless

The industry’s most consistent and compelling argument for why rent-to-own

is not credit is that customers can end the relationship at any time, surrender the

rented goods, and not be liable for the remaining lease payments. As the New Jersey

Supreme Court noted in Perez v. Rent-A-Center, however, this one fact is not deter-

minative on the issue of whether something is credit or something else.

126

Function-

ally, rent-to-own transactions involve non-recourse debt, a type of debt for which

the creditor does not seek additional payment after default, but relies solely on its

collateral post-default.

120

Payday Loan Consumer Information, CONSUMER FED’N AMERICA, https://

paydayloaninfo.org/state-information (last visited Dec. 21, 2020).

121

Miller, 518 N.W.2d at 546.

122

Id. at 548.

123

Nathalie Martin, Public Opinion and the Limits of State Law: The Case for Federal Usury

Caps, 34 N.

ILL. U. L. REV. 259, 266, 268–71 (2014).

124

Julia Kagan, Defining Limited Recourse Debt, INVESTOPEDIA, https://investopedia.com/

terms/l/limitedrecoursedebt.asp (last visited Dec. 20, 2020).

125

U.C.C. § 1-901(a) (AM. LAW. INST. & UNIF. LAW COMM’N 2019) (“. . . [T]his article

applies to . . . a transaction, regardless of its form, that creates a security interest in personal

property or fixtures by contract . . .”).

126

Perez v. Rent-a-Ctr., Inc., 892 A.2d 1255, 1270 (N.J. 2006).

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 167 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 167 Side A 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

2020] SHADOW CREDIT 1459

Non-recourse or limited recourse debt is debt for which the creditor agrees not

to pursue the borrower for any additional payments once it repossesses its collat-

eral.

127

With recourse debt, the lender has the legal right to collect not just from the

collateral, but also from the debtor’s other assets upon default.

128

Recourse debt can

either be full recourse or limited recourse.

129

Full recourse debt allows the lender to

seize and sell the debtor’s assets, through the state execution and collections pro-

cess.

130

Limited recourse or non-recourse debt contracts forbid the lender from collect-

ing except from limited assets, typically just its collateral.

131

This type of debt “gives

the lender a limited amount of recourse to the borrower’s other assets in the event

of default.”

132

If the borrower defaults on his or her payments, the lender can exer-

cise its rights to repossess its collateral, but that’s it. If the collateral is insufficient to

cover the entire debt, the borrower is not personally liable for the deficiency or

shortfall between the amount of unpaid debt and the amount realized on the collat-

eral.

133

Non-recourse loans are not limited to home loans.

134

Any time the lender relies

solely on the value of its collateral for collection, the debt is non-recourse debt. Rent-

to-own contracts create just that, non-recourse debt. It is not that the transactions

are leases, as both parties prefer that the customer ultimately own the property and

in most cases that is what happens.

135

Rather, rent-to-own transactions create debt

for which the lender intends to rely solely on its collateral for repayment. Rent-to-

own contracts in which the customer can end the relationship at any time by just

returning the goods have all of the attributes of non-recourse debt. Non-recourse

debt is debt, nevertheless.

2. The Side-Step Around Article 9

As we have seen, creditors extending credit on a secured or unsecured basis

benefit in many ways by calling their products something other than “credit.” One

127

Kagan, supra note 124.

128

Id.

129

Id.

130

Id.

131

Id.

132

Id.

133

Id.

134

For example, “[a]uction houses and art specialists, on the other hand, provide non-

recourse loans and their decisions are based solely on the value of the art and its risk. The

borrower’s guarantee is not required in order to approve a non-recourse loan, and the main

criterion is the art itself, not the creditworthiness of the borrower.” William N. Goetzmann &

Milad Nozari, Art as Collateral 5 (Yale ICF, Working Paper No. 2018-01, 2020),

https://ssrn.com/abstract=3099054.

135

Lacko, supra note 9, at ES-2.

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 167 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

42938-lcb_24-4 Sheet No. 167 Side B 02/02/2021 10:18:46

C M

Y K

Martin_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 1/18/2021 6:18 PM

1460 LEWIS & CLARK LAW REVIEW [Vol. 24.4

benefit is escaping the purview of Article 9 of the U.C.C., which governs reposses-

sions, forfeiture, and creditor liability. In the first scholarly article on rent-to-own,

Professor James Nehf noted the industry’s particular interest in avoiding Article 9’s

repossession provisions.

136

The scope of Article 9 has always been broad, to keep lenders from disguising

their transactions as leases for the purpose of escaping the protections of the U.C.C.

As one court explained:

[Article 9 was drafted, in part,] [t]o avoid the dismal history under which

legislatures drafted laws to govern security arrangements and clever lawyers

routinely escaped the grasp of such laws by devising ingenious documents that

suited their clients’ needs . . . . [The Code instructs that, with limited excep-

tions, Article 9 applies regardless of] whether title in collateral is in the secured

party or the debtor . . . . The drafters . . . took this step with the intention

“that its provisions should not be circumvented by manipulation of the locus

of title.”

137

Ensuring that Article 9 applies to disguised security interest is critical to, among

other things, avoiding forfeitures of equity similar to that which occurred in the

infamous Walker Furniture case, in which a low-income woman made most of her

installment payments on various household goods, but defaulted at the end and lost

everything.

138

The drafters of Article 9 also sought to avoid unfair collection and

repossession.

139

136

Nehf, supra note 59, at 752.

137

In re Jeff Benfield Nursery, Inc., 565 B.R. 603, 613 (Bankr. W.D.N.C. 2017).

138

Williams v. Walker-Thomas Furniture Co., 350 F.2d 445, 447 (D.C. Cir. 1965).

139

As Nehf explains:

If the agreement is deemed to have created a security interest, the state’s version of Article 9

will impose several restraints on the repossessing firm that do not apply to lessors. For in-

stance, after a dealer lawfully repossesses, the consumer has a right under section 9-506 to

cure the default by tendering the amount secured by the obligation. If default is not cured

and the dealer decides to retain the collateral (instead of selling it or re-renting it to another