The Long Term Care Community Coalition

209 West 29

th

Street, Suite 6252, New York, NY 10001

www.nursinghome411.org

©2021 The Long Term Care Community Coalition

A digital version of this report is available at

nursinghome411.org/survey-enforcement.

Broken Promises

An assessment of federal data on nursing home oversight

and the impact of lax enforcement on residents and families.

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

Table of Contents

I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 4

HOW TO READ THIS REPORT ............................................................................................................................................. 4

BACKGROUND: THE GOVERNMENT’S BROKEN PROMISES ...................................................................................................... 4

CMS REGIONAL OFFICES/LOCATIONS ................................................................................................................................ 7

METHODOLOGY, METRICS, & TERMINOLOGY ...................................................................................................................... 9

Survey Sample ...................................................................................................................................................... 9

Annual Citation Rates ........................................................................................................................................... 9

Antipsychotic Drugging and Pressure Ulcers ........................................................................................................ 9

LIMITATIONS ............................................................................................................................................................... 11

II. Data and Analysis .................................................................................................................. 12

OVERALL CITATIONS ..................................................................................................................................................... 12

Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 12

Key Findings ....................................................................................................................................................... 12

State Findings ..................................................................................................................................................... 13

Regional Findings ............................................................................................................................................... 13

Data: Map and Tables ........................................................................................................................................ 14

ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUGGING ........................................................................................................................................... 17

Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 17

Key Findings ....................................................................................................................................................... 18

Data: Maps and Tables ...................................................................................................................................... 19

INFECTION CONTROL .................................................................................................................................................... 22

Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 22

Key Findings ....................................................................................................................................................... 23

Data: Map and Tables ........................................................................................................................................ 24

PRESSURE ULCERS ........................................................................................................................................................ 27

Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 27

Key Findings ....................................................................................................................................................... 27

Data: Map and Tables ........................................................................................................................................ 28

QUALITY OF LIFE .......................................................................................................................................................... 31

Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 31

Key Findings ....................................................................................................................................................... 32

Data: Map and Tables ........................................................................................................................................ 33

RESIDENT RIGHTS ........................................................................................................................................................ 36

Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 36

Key Findings ....................................................................................................................................................... 37

Data: Map and Tables ........................................................................................................................................ 38

STAFFING ................................................................................................................................................................... 41

Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 41

Key Findings ....................................................................................................................................................... 42

Data: Map and Tables ........................................................................................................................................ 43

FINES......................................................................................................................................................................... 46

Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 46

Key Findings ....................................................................................................................................................... 46

Data: Map and Tables ........................................................................................................................................ 47

III. Discussion & Recommendations ........................................................................................... 50

DISCUSSION: A FAILURE TO ENFORCE .............................................................................................................................. 50

RECOMMENDATIONS: ................................................................................................................................................... 51

Long Term Care Community Coalition

3

IV. Appendix ................................................................................................................................ 54

SCOPE & SEVERITY GRID ............................................................................................................................................... 54

HEALTH DEFICIENCIES (2018-20)................................................................................................................................... 54

PAYROLL-BASED JOURNAL (PBJ) DATA (Q4 2019) ........................................................................................................... 55

MDS FREQUENCY REPORTS ........................................................................................................................................... 55

PENALTIES .................................................................................................................................................................. 55

F-TAG LIST ................................................................................................................................................................. 55

This report includes maps and tables developed using Tableau, a data

visualization software. For a more interactive and user-friendly experience,

we recommend viewing the online version of this report at

nursinghome411.org/survey-enforcement.

Visit www.nursinghome411.org for free resources including

fact sheets, webinars, staffing data, facility ratings, and more!

Questions? Contact us at [email protected].

This report was researched and written with the generous

support of The New York Community Trust.

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

I. Introduction

How to read this report

Part I (this introduction) provides critical background information on nursing home

enforcement and context for the data presented in this report and our findings. It also provides

useful information on the components of the research, including methodology, sources, and

the role of the CMS Regional Offices.

Part II (Data and Analysis) is the main section of this report, presenting data on and insights into

nursing home enforcement. It covers several key topics which we believe are both important

and useful in assessing the effectiveness of government efforts to ensure that nursing homes

are held accountable for providing good care, including Overall Citations, Antipsychotics,

Infection Control, Pressure Ulcers, Quality of Life, Resident Rights, Staffing, and Fines. Each

category includes:

• An introduction,

• Key findings,

• A map depicting rates of (1) state enforcement, (2) states’ identification of harm or immediate

jeopardy, (3) U.S. totals and averages,

• A table with state data, and

• A table with regional data.

Part III (Discussion & Recommendations) contains a discussion of our findings on oversight and

enforcement at the state, regional, and federal levels and how these data can inform public

policy moving forward. Further, it offers seven recommendations for CMS to ensure that State

Agencies – and the Regional Offices charged with overseeing them – fulfil their shared mission

to protect residents.

Part IV (Appendix) provides references and sources with links to original datasets.

Background: The Government’s Broken Promises

U.S. nursing homes provide care, support services, and housing to over one million people

every day and millions of people each year. In addition to those individuals, their families and

loved ones have a substantial personal stake in the quality of care and quality of life nursing

homes provide. With the advent of the aging “Baby Boomer” generations, these numbers will

undoubtedly rise. As reported in U.S. News and World Report, “[s]omeone turning age 65 today

has almost a 70% chance of needing some type of long-term care, and 20% of people will need

it for longer than five years.”

1

1

Levine, David and Esposito, Lisa, U.S. News and World Report, “How to Pay For Nursing Home Costs” (October 15,

2021), citing LongTermCare.gov. Available at http://health.usnews.com/health-news/best-nursing-

homes/articles/2013/02/26/how-to-pay-for-nursing-home-costs.

Long Term Care Community Coalition

5

While many of us have – or will have – a personal stake in nursing home care, all of us will share

a financial stake. Spending on care in U.S. nursing homes and continuing care retirement

communities totaled $168.5 billion in 2018.

2

The average rate for nursing home care in the U.S.

is now over $250 per day.

3

The large share of these costs is paid by taxpayers through the

Medicaid and Medicare programs.

Despite the significant need for both long-term and short-term nursing home care – and the

billions of dollars we invest every year – significant problems in resident care, quality of life, and

dignity are pervasive across the country. Our laws and regulatory standards are strong,

providing that each resident be treated with dignity and receive the care and services that

they need to attain, and maintain, their highest practicable physical, emotional, and social

well-being. The fact that this level of care is the exception, rather than the rule, is a result of

the failure (in fact multiple failures, every day) to adequately enforce those standards and

protections.

In short, nursing homes too often have inadequate

care staff and fail to provide appropriate care with

dignity because nothing is stopping them from doing

otherwise. As the data in this report indicate, the

government is breaking its promise to ensure that

residents are safe and treated with dignity. There is

often little or no punishment when nursing homes fail

to provide care that meets the standards they are paid

to achieve, even when such failures result in significant resident suffering or avoidable death.

The systemic acceptance of subpar care does not only perpetuate resident neglect and abuse;

it has a significant financial cost. As noted above, taxpayers pay for the majority of nursing

home care. We count on the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the

State Survey Agencies (SAs) to assure that public monies are spent appropriately. When care is

poor it means we are not getting good value for the money we spend. And when that poor care

results in the need for additional care, whether it be medication to fight an unnecessary

infection or hospitalization due to a medication error, the public foots the bill for that, too.

This report builds on LTCCC’s 2015 study, “Safeguarding NH Residents & Program Integrity: A

National Review of State Survey Agency Performance,”

4

which reviewed nursing home quality

2

National Center for Health Statistics, National health expenditures, average annual percent change, and percent

distribution, by type of expenditure: United States, selected years 1960–2018 (data compiled from various sources

by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-expenditures.htm

Note: CMS does not provide separate data for nursing homes and continuing care retirement communities.

3

Genworth, 2020 Cost of Care Survey. https://www.genworth.com/corporate/about-genworth/industry-

expertise/cost-of-care.html

4

https://nursinghome411.org/national-report-safeguarding-nh-residents-program-integrity-a-national-review-of-

state-survey-agency-performance/.

As the data in this report

indicate, the government is

breaking its promise to ensure

that residents are safe and

treated with dignity.

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

assurance indicators based on a resident-centered approach. Though oversight is typically

assessed on a facility basis, the 2015 study and this report assess enforcement rates adjusted for a

state’s nursing home resident population. In our view this is critical, since the purpose of nursing

home standards is to ensure that residents, as individuals, receive care that complies with

professional standards and are treated with dignity.

This report presents the results of an analysis of survey and enforcement data at the state,

regional, and federal levels with a focus on all U.S. states and the 10 Regional Offices of the

federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) tasked with overseeing the

performance of the state enforcement agencies in their respective regions of the country. To

assess performance in enforcement, we assessed the surveyor citation rate and citation

severity in seven critical areas of nursing home care based on surveys (inspections) over the

most recent three-year period (2018-20). These areas are:

• Overall Citations

• Antipsychotic Drugging,

• Infection Control,

• Pressure Ulcers,

• Quality of Life,

• Resident Rights, and

• Sufficient Staffing.

For each area of nursing home care, we provide key enforcement performance metrics

including citation rates (how often a state/region cited its nursing homes, adjusted for resident

population) and percent of G+ citations (the proportion of citations categorized as having

caused any resident harm or immediate jeopardy). Individual care categories (excluding Overall

Citations) also include examples of so-called "no harm” deficiencies (citations categorized as A

through F).

5

,

6

Note: Federal Fines (average dollar amount and frequency, adjusted for resident population) are

also assessed in this report.

States and regions are ranked in each enforcement performance metric (most

frequent/severe citation rates and penalties ranking first; least frequent/severe ranking last).

Wherever possible, we provide color-coded maps that illustrate state and regional disparities in

enforcement performance.

The wide range of enforcement data provided in this report can be used to identify strengths

and weaknesses among states in respect to their ability to ensure nursing home safety

5

Most “no harm” examples obtained from The Elder Justice “No Harm” Newsletter at

https://nursinghome411.org/news-reports/elder-justice/. The example provided in Quality of Life is available at

https://nursinghome411.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/QOL-F675-Pico-Rivera.pdf.

6

See the Appendix for the Scope & Severity Grid which surveyors used to rank deficiencies.

Long Term Care Community Coalition

7

standards are realized for their residents. Additionally, it can be used to gain insights into regional

trends based on performance among the 10 CMS Regional Offices covering the country. Lastly,

the federal data can be used to provide context for state and regional data, and in most cases,

demonstrate the universality of U.S. nursing home enforcement performance trends.

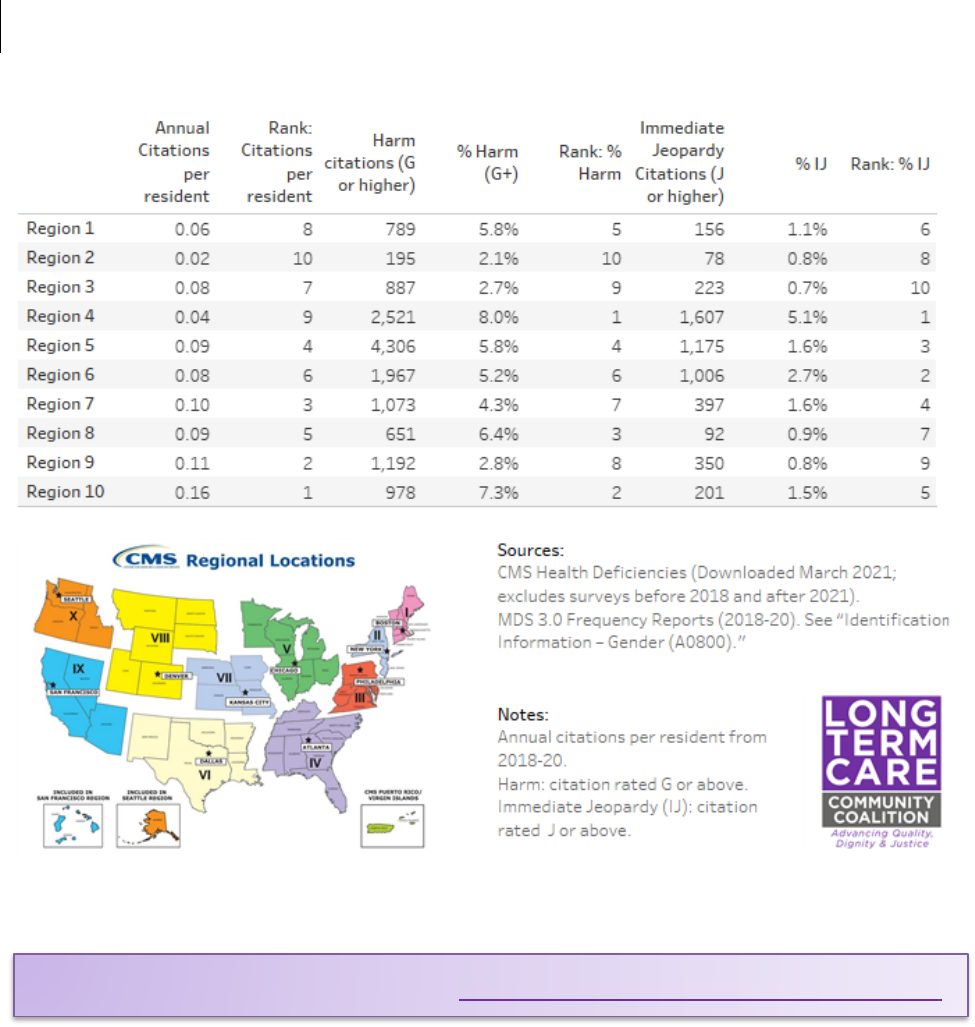

CMS Regional Offices/Locations

CMS’s Regional Offices are responsible for overseeing the enforcement agencies of the states

within their region of the country. The 10 regional offices are located in Boston, New York,

Philadelphia, Atlanta, Dallas, Kansas City, Chicago, Denver, San Francisco, and Seattle. More

information on each CMS Region and its nursing home demographics (based on MDS Reports)

7

are listed in the map and table below. Note: CMS has renamed the Regional Offices as

“Locations.” However (as of October 2021), the term “Regional Office” still appears on the CMS

website. For this reason, and because it is more descriptive, this report uses “Regional Office.”

7

MDS 3.0 Frequency Reports (Q4 2019) available at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-

Systems/Computer-Data-and-Systems/Minimum-Data-Set-3-0-Public-Reports/Minimum-Data-Set-3-0-Frequency-

Report.

Figure 1: Map of CMS Regional Locations.

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

CMS

Region

Regional

Office

Location

States

Resident

Population

(Avg.

2018-20)

% Non-

White

% 85+

%

Male

1

Boston

Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts,

New Hampshire, Rhode Island,

Vermont

81,394

14.6%

42.3%

35.2%

2

New York

New Jersey, New York, Puerto Rico,

Virgin Islands

147,034

35.5%

38.1%

38.6%

3

Philadelphia

Delaware, District of Columbia,

Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia,

West Virginia

142,490

24.2%

37.7%

36.0%

4

Atlanta

Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky,

Mississippi, North Carolina, South

Carolina, Tennessee

249,017

29.7%

32.8%

36.3%

5

Chicago

Illinois, Indiana, Michigan,

Minnesota, Ohio, Wisconsin

260,895

20.3%

35.5%

37.5%

6

Dallas

Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico,

Oklahoma, Texas

158,662

33.3%

31.9%

37.3%

7

Kansas City

Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska

87,815

11.5%

40.1%

35.5%

8

Denver

Colorado, Montana, North Dakota,

South Dakota, Utah, Wyoming

39,270

16.5%

38.3%

38.8%

9

San

Francisco

Arizona, California, Hawaii, Nevada,

Pacific Territories

124,822

45.4%

30.3%

43.0%

10

Seattle

Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, Washington

27,943

15.8%

30.1%

41.0%

Long Term Care Community Coalition

9

Methodology, Metrics, & Terminology

Survey Sample

This report explored citations from surveys conducted from 2018 to 2020. A total of 290,289

citations were recorded for surveys conducted during this three-year period.

8

See Appendix -

Health Deficiencies (2018-20) for more on citations data.

Federal rules require that the state survey agencies conduct a standard survey of their state’s

nursing homes, evaluating compliance with minimum standards, on average of once every 12

months (with a window of 9-15 months for an individual facility’s inspection). Though the

COVID-19 pandemic led to restrictions on state survey agency activities during 2020, we

determined to include citations for this year to provide the most up-to-date data and gain

insights into variations in enforcement during this period.

Annual Citation Rates

Annual citation rates for most categories (Overall Citations, Infection Control, Quality of Life,

Resident Rights, and Sufficient Staffing) were calculated per total resident population (based

on MDS 3.0 Frequency Reports from 2018-20).

9

Some citations were scaled to per 100, per

1,000, or per 10,000 residents.

Annual citation rates were determined by dividing the three-year rate by three.

Antipsychotic Drugging and Pressure Ulcers

Citation rates for Inappropriate Antipsychotic Drugging and Substandard Pressure Ulcer Care

were calculated by dividing the number of AP and PU citations, respectively, by the number of

residents receiving antipsychotics (RAP) and the number of residents diagnosed with unhealed

pressure ulcers (RPU) during the fourth quarter of 2019, based on MDS data.

10

These metrics

are referred to as RAP Citation Rate and RPU Citation Rate. This methodology was chosen to

reflect the specific information we have on reported residents receiving antipsychotics and

those with identified (and reported) pressure ulcers. The fourth quarter of 2019 was selected

because it is the most recent full quarter prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

8

Citation data based on CMS’s Health Deficiencies which include health citations from surveys conducted in the

three-year period from 2018 to 2020. Downloaded March 2021. Most recent dataset available at:

https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/dataset/r5ix-sfxw.

9

Average residents in 12 quarterly MDS 3.0 Frequency Reports (“A0800: Identification Information – Gender) from

2018-20. Available at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Computer-Data-and-

Systems/Minimum-Data-Set-3-0-Public-Reports/Minimum-Data-Set-3-0-Frequency-Report.

10

MDS 3.0 Frequency Reports (Q4 2019) for antipsychotics (N0410A: Medications - Medications Received –

Antipsychotics) and pressure ulcers (M0210: Skin Conditions - Unhealed Pressure Ulcers). Available at

https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Computer-Data-and-Systems/Minimum-Data-Set-3-

0-Public-Reports/Minimum-Data-Set-3-0-Frequency-Report.

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

Antipsychotic Drugging Acronyms

AP = Antipsychotic drug

RAP = Number of residents receiving antipsychotics

RAP % = Percentage of total residents receiving

antipsychotics

AP Citation Rate = Number of AP citations per total

resident population

RAP Citation Rate = Number of antipsychotic drugging citations per 1k residents receiving

antipsychotics

Pressure Ulcer Acronyms

PU = Pressure Ulcers

RPU = Number of residents with a reported pressure ulcer

RPU % = Percentage of total residents with reported

pressure ulcers

PU Citation Rate = Number of PU citations per total

resident population

RPU Citation Rate = Number of PU citations per 100

residents with reported pressure ulcers

“Harm” and “Immediate Jeopardy”

CMS categorizes deficiencies into four levels of severity based on letters A through L.

Level 1: No actual harm with potential for minimal harm (A, B, C).

Level 2: No actual harm with potential for more than minimal harm that is not immediate

jeopardy (D, E, F).

Level 3: Actual harm that is not immediate jeopardy (G, H, I).

Level 4: Immediate jeopardy to resident health or safety (J, K, L).

Key Harm and Immediate Jeopardy metrics:

• % G+ Citations: Number of G+ citations (G, H, I, J, K L) / total citations (A through L).

• % Immediate Jeopardy Citations: Number of J, K, or L citations / total citations (A through L).

Note: In this report, we review state, regional, and national citation rates by 1) Overall citations

(no matter the severity) and 2) G+ citations (those in which the surveyors have found either

harm or immediate jeopardy). This distinction is important. Overall citation rates reflect the

extent to which state surveyors have identified a violation of minimum standards. However, the

RAP Citation Rate measures

the number of antipsychotic

drugging citations per 1,000

residents receiving

antipsychotics (RAP).

RPU Citation Rate measures

the number of PU citations

per 100 residents with

reported pressure ulcers

(RPU).

Long Term Care Community Coalition

11

identification of resident harm is critical because, in the absence of identification of harm, it is

extremely unlikely that a facility will face any penalty.

11

Limitations

This report offers a wide variety of data on nursing home enforcement at the state and regional

levels. It can be used to inform consumers, legislators, and the public during a critical moment

in long-term care policymaking.

Limitations include:

• Data accuracy: Datasets may provide varying levels of accuracy. For example, recent reports

have indicated an underreporting of rates of both pressure ulcers

12

and antipsychotic

drugging

13

of residents.

• State/regional differences: Conditions in a certain state/region may contribute to differences

in performance metrics in nursing home care and/or nursing home enforcement. For

example, unique geographic conditions in Alaska (as well as the state’s small population) may

create different environments for surveyors that could lead to differences in enforcement

performance metrics. Further, differences in resident demographics (i.e., age/race/gender)

may contribute to disparities in care and/or enforcement outcomes.

14

• Limited surveys in 2020 due to COVID-19: In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, CMS

limited state survey agency activity nationwide for a good part of 2020 to infection control

surveys and investigations of allegations of immediate jeopardy. This led to fewer surveys and

citations than normally occur in a year. Only 52,000 citations were recorded in 2020

compared to 124,000 in 2019 and 115,000 in 2018. However, since the COVID-19 restrictions

on state survey agencies were imposed nationwide, we determined that it would be most

useful to include citations for this year since it provides the most up-to-date data available, as

well as insights into how states and regions responded to the pandemic.

11

For more information and insights into the identification of resident harm, see The Elder Justice “No Harm”

Newsletter at https://nursinghome411.org/news-reports/elder-justice/.

12

Integra Med Analytics, Underreporting in Nursing Home Quality Measures (Aug 25, 2020).

https://www.nursinghomereporting.com/post/underreporting-in-nursing-home-quality-measures

13

Thomas, K., Gebeloff, R., and Silver-Greenberg, J., The New York Times, “Phony Diagnoses Hide High Rates of

Drugging at Nursing Homes,” (Sept 11, 2021). https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/11/health/nursing-homes-

schizophrenia-antipsychotics.html

14

While an investigation of the potential impact of disparities in the resident population on state or regional

survey performance is beyond the scope of this study, the authors hope that these data may be useful for further

research in this area.

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

II. Data and Analysis

Overall Citations

Introduction

• Fundamentally, a state’s oversight of nursing home care boils down to two components: (1)

its ability to identify and cite a facility when a failure to meet standards (i.e., a deficiency)

exists and (2) its ability to appropriately rate the deficiencies it finds in terms of their “scope

and severity.”

• This section provides baseline information on the extent to which states are substantiating

problems and identifying when they result in harm or immediate jeopardy to one or more

residents (i.e., a rating of G or higher in the federal scope and severity grid).

15

It contains state

and regional data on overall citations including key findings, a map data visualization, and

tables.

• The accurate identification and rating of harm or immediate jeopardy is crucial because, in the

absence of such a finding, it is highly unlikely that the facility will be penalized for the

substandard care, abuse, or neglect. In other words, a facility will generally face no negative

repercussions for substandard care unless harm or immediate jeopardy are identified by the

state survey agency.

Key Findings

• Annually, surveyors substantiated one violation for every 13 nursing home residents in the

three-year period from 2018 to 2020 (0.07 citations per resident per year).

• Of the 290,289 total citations over three years, 95% were identified as causing neither harm

nor immediate jeopardy to any resident in the facility (5% were categorized as Harm (G or

above), including 1.8% of citations that were Immediate Jeopardy (J or above)).

• Infection Prevention & Control (F880) citations accounted for 7.8% of all deficiencies. As the

U.S. Government Accountability Office noted in a May 2020 report, “most nursing homes

were cited for infection prevention and control deficiencies (82% of those surveyed from

2013-2017). About half of these homes had persistent problems and were cited across

multiple years.”

16

15

See the Appendix for the scope and severity grid used by surveyors to rate deficiencies. For more information on

the role of the state survey agencies, see “A Practical Guide to the State Operations Manual,” available at

nursinghome411.org/survey-enforcement.

16

Infection Control Deficiencies Were Widespread and Persistent in Nursing Homes Prior to COVID-19 Pandemic,

GAO-20-576R (May 20, 2020). Available at https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-576r.

Long Term Care Community Coalition

13

• Antipsychotics (F758), Pressure Ulcers (F686), and Resident Rights (F550) are issues of concern

to both state and federal policymakers (not to mention residents and their families). Yet they

only accounted for roughly 2% of citations (each).

• Though most U.S. nursing homes persistently fail to meet CMS’s threshold for safe staffing,

Sufficient Staffing (F725) accounted for just 1% of citations.

• Quality of Life (F675) is crucial for residents and an essential component of the federal

requirements for nursing homes. Yet violations of a resident’s right to a decent quality of life

and treatment with dignity accounted for only 0.1% of citations.

State Findings

• State citation levels and identification of harm or immediate jeopardy (G+ on the scope and

severity scale) varied considerably.

• State enforcement in both citation rates and identification of harm or immediate jeopardy

were largely consistent across the categories of nursing home care evaluated in this study.

• In an average year in New York, which had the lowest citation rate in the country, there was

one citation for every 50 residents. In Alaska, which had the highest citation rate in the

country, there was one citation for every four residents.

• Our analysis did not reveal a strong association between a state’s enforcement frequency

(citation rate) and the likelihood that it would identify resident harm or immediate jeopardy

when making a citation.

• New Jersey and New York, both of which are in CMS Region 2, ranked in the bottom-quintile

in most citation rate metrics evaluated in this report.

Regional Findings

• As with the states, regional enforcement rates and the extent to which harm or immediate

jeopardy were identified varied considerably. Regional performance was often consistent

across the categories we assessed.

• Region 2 ranked at the bottom on most enforcement metrics. Region 10 ranked first or

second in most enforcement metrics. Region 10 is the least populated CMS region.

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

Data: Map and Tables

Total Citation Rate and Severity by State (2018-20)

Figure 2: Annual citations per resident during the three-year period from 2018-20. Darker shades indicate lower citation rates;

larger circles indicate lower proportion of Harm (G+) citations. See Figure 3 for info on Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico.

Long Term Care Community Coalition

15

Figure 2: Citation rate and severity by state (2018-20).

Long Term Care Community Coalition

17

Antipsychotic Drugging

Introduction

• Antipsychotic (AP) medications are highly potent drugs that are indicated to treat specific

conditions and diagnoses, such as schizophrenia. Unfortunately, inappropriate antipsychotic

drugging of nursing home residents, particularly those with dementia, is a prevalent problem

in facilities across the country. Too often, these drugs are used as a form of chemical restraint,

to sedate residents rather than provide appropriate care.

17

• AP drugs carry a “black-box” warning from

the Food and Drug Administration

18

because

they greatly increase the risks of stroke,

heart attack, diabetes, Parkinsonism, and

falls. They can also significantly diminish

social and emotional well-being. Importantly,

these drugs are not clinically indicated for the

treatment of the so-called behavioral and

psychological symptoms of dementia.

• A September 2021 New York Times report,

“Phony Diagnoses Hide High Rates of

Drugging at Nursing Homes,” found that

diagnoses of schizophrenia among nursing

home residents have increased dramatically in the years since CMS launched its “Partnership”

to improve dementia care and reduce antipsychotic drugging. This is likely because a nursing

home’s publicly reported rate of antipsychotic drugging is risk-adjusted to exclude residents

who receive these drugs but have been given a diagnosis of schizophrenia, Huntington’s

Disease, or Tourette’s Syndrome.

19

• This section contains state and regional data on AP drugging rates and AP citations (F758 -

Free from Unnecessary Psychotropic Meds/PRN Use), including key findings, a map data

visualization, and tables. Note: F758 comprises citations for any inappropriate psychotropic

drugging. Thus, it captures inappropriate antipsychotic drugging as well as the inappropriate

17

For more information and resources on the inappropriate use of antipsychotic drugs in nursing homes, visit our

Dementia Care Advocacy Toolkit at https://nursinghome411.org/learn/dementia-care-advocacy-toolkit/.

18

Public Health Advisory: Deaths with Antipsychotics in Elderly Patients with Behavioral Disturbances, U.S. Food

and Drug Administration (April 11, 2005). Available in the FDA’s archived web page, https://wayback.archive-

it.org/7993/20170113112252/http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatient

sandProviders/ucm053171.htm.

19

Thomas, Katie, Gebeloff, Robert, and Silver-Greenberg, Jessica, “Phony Diagnoses Hide High Rates of Drugging at

Nursing Homes,” The New York Times (Sep 11, 2021). Available at

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/11/health/nursing-homes-schizophrenia-antipsychotics.html.

No stop date: A “No Harm”

Antipsychotics Deficiency (F758)

At a Florida nursing home, a resident

was receiving PRN (as needed)

antipsychotic medication for several

months without justification for

ongoing use and without a stop date on

the order. Despite the risks posed by

the potentially life-threatening side-

effects of psychotropics, the surveyor

cited the violation as no harm.

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

use of other psychoactive drugs, such as antidepressants. There is no F-tag that solely

addresses antipsychotics.

• Methodology: Citation Rates for inappropriate antipsychotic drugging (RAP Citation Rate)

were calculated based on AP citations (F758) from 2018-20 and the number of residents

receiving antipsychotics (RAP) in the fourth quarter of 2019 (MDS 3.0 Frequency Report (Q4

2019), N0410A: Medications - Medications Received - Antipsychotic).

Key Findings

• Though the use of chemical restraints has been prohibited for 30 years, and CMS has focused

specifically on eliminating the inappropriate use of AP drugs in U.S nursing homes since 2012,

close to 20% of facility residents – over a quarter-

million people – were administered one or more

antipsychotic drug.

• Federal data indicate an average of just eight (8.1) AP

citations per year for every 1,000 residents reported to

be receiving antipsychotics.

• Of the 6,157 AP citations recorded over the entire three-

year period, 31 (less than one percent) were categorized

as harm (G+). In other words, even when surveyors substantiate inappropriate resident

drugging, 99.5% of the time they find no resident harm.

• CMS Region 2 (NJ, NY, PR) ranked at the bottom in respect to annual citation rates, recording

8.1 AP citations for every 1,000 RAP. Regions 1 and 2 recorded zero G+ AP citations, meaning

that surveyors in those regions never identified inappropriate drugging as harmful to

residents. Regions 3, 4, and 8 each recorded 1 citation at G+.

• Region 10 (serving the northwest) ranked 1st in Annual RAP citation rate (26.1 per 1k

residents) and in % Harm AP citations (1.35%).

• Smaller states/territories including Alaska, Puerto Rico, Wyoming, Utah, Oregon, Delaware,

Idaho, and Hawaii recorded higher RAP citation rates, while Washington and Oregon ranked

in the top 10.

• The states with the lowest RAP citation rates (Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, Kentucky,

Georgia) were all located in the southern United States in Regions 4 and 6 (see Figure 6).

• These findings indicate that, despite years of training for both state surveyors and nursing

home staff on the dangers of antipsychotic drugs,

o Widespread antipsychotic drugging persists and

o State surveyors are disinclined to hold nursing home accountable for it.

What is RAP Citation Rate?

RAP Citation Rate measures

the number of antipsychotic

drugging citations per 1,000

residents receiving

antipsychotics (RAP).

Long Term Care Community Coalition

19

• A Journal of the American Geriatrics Society

20

study found disproportionate increases in

schizophrenia diagnoses among Black nursing home residents with Alzheimer's and related

dementia (ADRD). Correlation analysis of our data indicates a weak-moderate (r=-0.35)

negative association between a state’s share of Black residents and its RAP citation rate. In

other words, states with more Black residents were less likely to identify AP drugging

violations, adjusting for share of populations receiving antipsychotics.

Data: Maps and Tables

RAP Antipsychotic Citation Rate and Severity by State (2018-20)

20

Fashaw-Walters, Shekinah, McCreedy, Ellen, Bynum, Julie, Thomas, Kali, and Shireman, Theresa,

“Disproportionate increases in schizophrenia diagnoses among Black nursing home residents with ADRD,” Journal

of the American Geriatrics Society (Sep 30, 2021). Available at

https://agsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jgs.17464.

Figure 5: Annual RAP Citation Rate (AP citations (F758) per 1k residents receiving antipsychotics) during the three-year period

from 2018-20. Darker shades indicate lower RAP rates; larger circles indicate lower proportion of Harm (G+) citation. See Figure

6 for info on Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico.

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

Figure 6: RAP citation (F758) rate and AP citation severity by state (2018-20).

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

Infection Control

Introduction

• Substandard infection prevention and control practices are a longstanding and widespread

problem in U.S. nursing homes.

• According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1 to 3 million serious

infections occur every year in nursing home and assisted living facilities and as many as

388,000 residents die each year due to infections.

21

[Note: This figure was reported prior to

the COVID-19 pandemic.]

• The U.S. Government Accountability Office found that, prior to the pandemic, “most nursing

homes were cited for infection prevention and control deficiencies (82% of those surveyed

from 2013-2017). About half of these homes had persistent problems and were cited across

multiple years.”

22

• The extent of inadequate infection

prevention and control practices in U.S.

nursing homes was a growing concern in

the years prior to the pandemic. In fact,

when CMS revised the federal

requirements for nursing homes in 2016,

one of the few substantive changes it

made was to require that nursing homes

have an infection preventionist on, at

least, a part-time basis.

• Many infections can be prevented and

controlled through basic precautions,

such as hand hygiene. Even in respect to

addressing the spread of COVID-19, both

the CDC and CMS focused on providing

education to the nursing home industry on basic sanitary protocols, such a “cough etiquette”

and the aforementioned hand hygiene.

21

https://www.cdc.gov/longtermcare/index.html.

22

Infection Control Deficiencies Were Widespread and Persistent in Nursing Homes Prior to COVID-19 Pandemic,

GAO-20-576R (May 20, 2020). Available at https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-576r.

Communal COVID dining: A “No Harm”

Infection Control Deficiency (F880)

In May 2020, a New York nursing home

continued communal dining and

violating COVID-19 health and safety

protocols at the peak of the pandemic.

Observations revealed 27 residents

seated in the dining room, most

unmasked and within six feet of each

other. The citation was cited as no

harm despite the facility’s failure to

provide a safe environment to help

prevent the spread of COVID.

Long Term Care Community Coalition

23

• In August 2020, then CMS administrator Seema Verma “warned nursing home operators that

‘significant deficiencies in infection control practices’ were responsible for increases in COVID-

19 deaths.”

23

• This section contains state and regional data on Infection control citations (F880 - Infection

Prevention & Control), including key findings, a map data visualization, and tables.

Key Findings

• Infection Control (F880) accounted for 7.8% of all deficiencies identified by surveyors during

the three-year period we reviewed. Annually, this was an average of 5.7 citations for every

1,000 residents in U.S. nursing homes.

• Of the 22,554 infection control citations, only 3.2% were categorized as causing harm or

putting any residents in immediate jeopardy (G+). This indicates that state surveyors rarely

identify substandard infection control practices as a serious problem or significant threat to

residents. As discussed in the introduction to this report, in the absence if identification of

harm or immediate jeopardy, a facility is unlikely to face any penalty. Essentially, from a

consumer perspective, this means that facilities are paid for deficient practices.

• Even in 2020, during which COVID-19 decimated nursing homes, state surveyors failed to

identify any harm or immediate jeopardy to a single resident 93.5% of the time that they

found inadequate infection control practices.

• East coast states (New York, Vermont, Georgia, New Hampshire, North Carolina) reported the

lowest IC citation rates

24

(see Figure 8).

• Region 2’s annual citation rate (2.1 per 1,000 residents) was roughly one quarter that of

Region 9’s (8.2). In other words, the federal data indicate that states in Region 9 (California,

Nevada, and Arizona) are roughly four times more likely than those in Region 2 (New York,

New Jersey, and Puerto Rico) to identify inadequate infection control practices in their state’s

nursing homes.

23

Jaffe, Susan, “Three States Limit Nursing Home Profits in Bid to Improve Care,” Annals of Long-Term Care (Oct

25, 2021). Available at https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/altc/news/three-states-limit-nursing-

home-profits-bid-improve-care?hmpid=dXNjZG9jQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==.

24

States are listed in ascending order (i.e., NY had the lowest infection control citation rate in the country).

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

Data: Map and Tables

Infection Control Citation Rate and Severity by State (2018-20)

Figure 8: Annual Infection Control citations (F880) per 1k residents during the three-year period from 2018-20. Darker shades

indicate lower IC citation rates; larger circles indicate lower proportion of Harm (G+) citations. See Figure 9 for info on Alaska,

Hawaii, and Puerto Rico.

Long Term Care Community Coalition

25

Figure 9: Infection Control (F880) citation rate and severity by state (2018-20).

Long Term Care Community Coalition

27

Pressure Ulcers

Introduction

• According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “[p]ressure ulcers, also known as

bed sores… are serious medical conditions and one of the important measures of the quality

of clinical care in nursing homes.”

25

• While some pressure ulcers are unavoidable,

research indicates that, “[i]n the vast majority of

cases, appropriate identification and mitigation of risk

factors can prevent or minimize pressure ulcer (PU)

formation.”

26

• Nevertheless, 7.26% of U.S. nursing home residents

have unhealed pressure ulcers. This is likely a

significant undercount, since studies have found that

many nursing homes under-report these data.

27

• This section contains state and regional data on

pressure ulcer (PU) rates and citations (F686 -

Treatment/Services to Prevent/Heal Pressure Ulcers),

including key findings, a map data visualization, and

tables.

• Methodology: Citation Rates for pressure ulcers (PUs) were calculated based on PU citations

and the number of residents with unhealed pressure ulcers in the fourth quarter of 2019

(MDS 3.0 Frequency Report (Q4 2019), M0210: Skin Conditions - Unhealed Pressure Ulcers).

Key Findings

• Pressure ulcers are a problem for over 92,000 nursing home residents.

• Though they are a serious problem and largely preventable or treatable, states cite nursing

homes the equivalent of less than 3% of the time that a resident has a pressure ulcer.

25

NCHS Data Brief, No. 14 (Feb 2009), which incorporates Pressure Ulcers Among Nursing Home Residents: United

States, 2004. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db14.pdf.

26

Edsberg, L.; Langemo, D.; Baharestani, M.; Posthauer, M.; and Goldberg, M., “Unavoidable Pressure Injury: State

of the Science and Consensus Outcomes,” Journal of Wound, Ostomy & Continence Nursing: July/August 2014 -

Volume 41 - Issue 4 - p 313–334. Abstract available at

http://journals.lww.com/jwocnonline/Abstract/2014/07000/Unavoidable_Pressure_Injury__State_of_the_Science

.6.aspx.

27

See, for example, Integra Med Analytics, Underreporting in Nursing Home Quality Measures (Aug 2020), finding

that “over half of SNFs [nursing homes] under-reported by at least a factor of two.” Available at

https://www.nursinghomereporting.com/post/underreporting-in-nursing-home-quality-measures.

A wound unhealed: A “No Harm”

Pressure Ulcer Deficiency (F686)

At a Delaware nursing home, a

resident suffering a stage 3

pressure ulcer (an open, sunken

hole) was not turned or

repositioned by staff as the

facility’s skin practice guide

directed. The surveyor found that

the facility violated standard

recommended interventions for

pressure ulcers but did not cite

the deficiency as harm.

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

• Annual PU citation rates varied considerably by region and state. In Region 10, citation rates

for residents with an identified pressure ulcer (5.2 per 100) occurred at 12 times the rate as

they did in Region 2 (0.4 per 100).

• When States do cite a facility for inadequate pressure

ulcer care or prevention, they only identify this as

harmful to residents about 23% of the time. Since, by

definition, a pressure ulcer is a wound, what message

does this send to the industry? To the state’s residents

and families?

• The ability to identify resident harm varied by region and

state. In Region 10, 45% of PU citations were ranked as G+ compared to only 10% in Region 2.

• Identification of any resident harm resulting from substandard pressure ulcer care is rare in

many states. DC, Maine, and Puerto Rico failed to record a single G+ PU citation in the three-

year period while Alabama, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Vermont recorded

only one (1) PU citation as causing resident harm over the three-year period (see Figure 12).

As a result, for example, the data indicate that even when New Jersey surveyors substantiate

substandard pressure ulcer care in a nursing home, they only identify this as harmful to

residents 3% of the time.

Data: Map and Tables

RPU Pressure Ulcer Citation Rate and Severity by State (2018-20)

What is RPU Citation Rate?

RPU Citation Rate measures

the number of PU citations

per 100 residents with

reported pressure ulcers

(RPU).

Figure 11: Annual RPU Citation Rate (PU citations (F686) per 100 residents with unhealed pressure ulcers) during the three-year

period from 2018-20. Darker shades indicate lower RPU rates; larger circles indicate lower proportion of Harm (G+) citations. See

Figure 12 for info on Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico.

Long Term Care Community Coalition

29

Figure 12: RPU citation (F686) rate and PU citation severity by state (2018-20).

Long Term Care Community Coalition

31

Quality of Life

Introduction

• The 1987 federal Nursing Home Reform Law clearly recognizes Quality of Life (QOL) as an

integral and essential component of an individual’s overall well-being.

• The federal regulations for nursing homes reflect this importance, stating explicitly that

“[q]uality of life is a fundamental principle that applies to all care and services provided to

facility residents. Each resident must receive, and the facility must provide the necessary care

and services to attain or maintain the highest practicable physical, mental, and psychosocial

well-being, consistent with the resident's comprehensive assessment and plan of care.”

28

• The CMS guidance makes clear the intent of this requirement:

The intent of this requirement is to specify the facility’s responsibility to create and

sustain an environment that humanizes and individualizes each resident’s quality of life

by:

o Ensuring all staff, across all shifts and departments, understand the principles of

quality of life, and honor and support these principles for each resident; and

o Ensuring that the care and services provided are person-centered, and honor and

support each resident’s preferences, choices, values, and beliefs.

29

• The COVID-19 pandemic exposed both the importance of QOL to resident well-being and the

extent to which the nursing home industry was unprepared to meet their needs when

visitation was stopped. According to an assessment conducted for The Associated Press, “for

every two COVID-19 victims in long-term care, there is another who died prematurely of

other causes.”

30

• This section contains state and regional data on QOL citations (F675), including key findings, a

map data visualization, and tables.

28

42 CFR 483.24. Available at https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-42/chapter-IV/subchapter-G/part-483#483.24.

29

CMS State Operations Manual, Appendix PP - Guidance to Surveyors for Long Term Care Facilities (Rev. 173, 11-

22-17). For more information, see LTCCC’s Fact Sheet: Dignity & Quality of Life Standards and other resources on

the federal guidelines in the Learning Center at www.nursinghome411.org/.

30

Sedensky, Matt and Condon, Bernard, “Not just COVID: Nursing home neglect deaths surge in shadows” (Nov 19,

2020). Available at https://apnews.com/article/nursing-homes-neglect-death-surge-

3b74a2202140c5a6b5cf05cdf0ea4f32.

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

Key Findings

• Quality of Life (F675) citations are rare, accounting

for one-tenth of one percent (0.1%) of all citations in

the three years we analyzed. Nationwide, the failure

to meet a resident’s quality of life needs and rights

was cited by surveyors at an annual rate of only 0.8

for every 10,000 residents.

• Of the 330 QOL citations reported nationwide from

2018-20, only 22 (6.7%) were categorized as Harm

(G+). In most states, surveyors never identified a

single instance in which a resident suffered harm

because of a QOL violation during the three-year

period assessed.

• Annual QOL citation rates exceeded 2 per 10k

residents in only four states: Alaska, California, DC,

and Montana (see Figure 15).

• Though citations for violating residents’ rights to a decent quality of life were miniscule

nationwide, variations among the CMS Regions were found. Region 9 (AZ, CA, HI, NV) had the

highest annual QOL citation rate (2.1 per 10k residents); Region 2 (NJ, NY, PR) had the lowest,

with a rate (0.2 per 10k residents), roughly one-tenth that of Region 9.

• These data indicate a profound disconnect between the regulatory requirements for resident

quality of life – including treatment with dignity and humanity – and their enforcement. The

federal guidelines state that specific principles of quality of life “will be used for determining

whether a resident’s quality of life is being supported and or enhanced” by a nursing home

and its staff. Yet, as our findings indicate, citations are exceedingly rare.

• This problem may be due, at least in part, to the CMS guidance being self-contradictory.

Though the requirements and their intent (as discussed in the above introduction) clearly

mandate a resident-centered approach that fosters dignity, choice, and self-determination,

the guidance also states that “[n]oncompliance at F675 identifies outcomes which rise to the

level of immediate jeopardy and reflect an environment of pervasive disregard for the quality

of life of the facility’s residents.” As discussed throughout this report, federal data show that

surveyors are extremely disinclined to cite a facility at the level of Immediate Jeopardy (IJ).

Thus, stating that a problem should be “pervasive” and rise to the level of IJ sends a message

that undermines the implementation of these important standards in the lives of residents.

[Though, as discussed above, less than seven percent (7%) of QOL citations are cited at a level

of harm or higher, indicating that surveyors are not understanding or correctly implementing

the guidance.] We strongly recommend that CMS resolve this conflict and take immediate,

meaningful steps to ensure that surveyors are effectively enforcing quality of life

requirements.

Don’t you know that it’s toxic:

A “No Harm” Quality of Life

Deficiency (F675)

At a California nursing home,

staff failed to monitor a

resident’s medication serum

levels. Though the resident

was put at greater risk of drug

toxicity and symptoms such as

muscle weakness, twitching,

blurred vision, confusion, and

dehydration, the violation was

not cited as causing harm or

immediate jeopardy.

Long Term Care Community Coalition

33

Data: Map and Tables

Quality of Life Citation Rate by State (2018-20)

Figure 14: Annual Quality of Life citations (F675) per 10k residents during the three-year period from 2018-20. Darker shades

indicate lower QOL citation rates. See Figure 15 for info on Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico.

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

Figure 4: Quality of Life (F675) citation rate and severity by state (2018-20).

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

Resident Rights

Introduction

• Under federal law, every nursing home resident has a right to a dignified existence, self-

determination, and communication with and access to persons and services inside and

outside the facility.

• The federal rules for nursing homes include the following requirements related to resident

rights:

o A facility must treat each resident

with respect and dignity and care

for each resident in a manner and in

an environment that promotes

maintenance or enhancement of

their quality of life, recognizing each

resident’s individuality;

o The facility must protect and

promote the rights of the resident;

o The facility must provide equal

access to quality care regardless of

diagnosis, severity of condition, or

payment source.; and

o A facility must establish and maintain identical policies and practices regarding

transfer, discharge, and the provision of services for all residents regardless of

payment source.

31

• CMS guidance explicitly states:

Each resident has the right to be treated with dignity and respect. All

staff activities and interactions with residents must focus on assisting

the resident in maintaining and enhancing his or her self-esteem and

self-worth and incorporating the resident’s preferences and choices.

Staff must respect each resident’s individuality when providing care

and services while honoring and valuing their input.

32

31

See LTCCC’s Fact Sheet: The Foundations of Resident Rights (referencing 42 CFR 483.10(a)), Resident Rights

Handouts, and other materials in our Learning Center, https://nursinghome411.org/learn/, for more information.

32

CMS State Operations Manual, Appendix PP, Resident Rights, Intent of §483.10(a)-(b)(1)&(2). Available at

https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-

Certification/GuidanceforLawsAndRegulations/Downloads/Appendix-PP-State-Operations-Manual.pdf.

Breakfast in a soiled bed: A “No Harm”

Resident Rights Deficiency (F550)

At a New York nursing home, a resident

was observed sitting naked while eating

from a tray placed on soiled linens. On

the floor next to the resident was a

soiled incontinence brief. Despite the

unsanitary and disrespectful conditions,

and the resident’s discomfort, this was

not cited as harm.

Long Term Care Community Coalition

37

• Despite strong requirements to foster and protect a resident’s rights, violations of these rights

are consistently the most widespread concern reported to the LTC Ombudsman Programs

across the country.

33

• This section of the report contains state and regional data on RR citations (F550), including key

findings, a map data visualization, and tables.

Key Findings

• Though, as noted above, resident rights violations are the most frequently raised complaint to

LTC Ombudsmen, Resident Rights (F550) accounted for only 2.0% of all state survey agency

citations reported during the three-year period. Annually, there was the equivalent of 1.5 RR

citation for every 1,000 nursing home residents.

• Only 74 (1.3%) of the 5,905 RR citations were categorized as Harm (G+). In other words, close

to 99% of the time that surveyors identify a violation of a resident’s rights they find that it

caused no harm to the resident. As discussed in the introduction to this report, in the

absence of a finding of harm or immediate jeopardy, it is extremely unlikely that a facility will

face any penalty for the substandard care or treatment. Practically speaking, this means that

nursing homes will get paid for treatment that violates the rights of their residents and not

have to worry about incurring fines or penalties for providing demeaning care or services.

• Federal data reveal that 23 states never identify any resident harm when they cite for a

violation of nursing home resident rights, based on the three years evaluated (see Figure 18).

• All but two states, Vermont, and Montana, identify resident harm less than 10% of the time

that they substantiate a violation of resident rights. However, both of those states scored in

the bottom half of the country in respect to the overall identification of resident rights

violations (i.e., at any level of scope or severity).

• Puerto Rico, Alaska, Washington, and Delaware – four of the least populated states – had the

highest rates of RR citations (see Figure 17).

• Region 2 (NJ, NY, PR) and Region 4 (serving the southeast) reported the lowest RR citation

rates; Regions 10 (northwest) and Region 9 (west) reported the highest (see Figure 19).

33

See LTC Ombudsman National and State Data, Administration for Community Living, Table A-3: Complaint

Summary: Nursing Facility Totals and Percents for FY 2015 as of 03/14/2017 (showing percentages of complaints

by group for the years 2010 – 2015). Available at https://acl.gov/programs/long-term-care-ombudsman/ltc-

ombudsman-national-and-state-data.

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

Data: Map and Tables

Resident Rights Citation Rate and Severity by State (2018-20)

Figure 6: Annual Resident Rights citations (F550) per 1k residents during the three-year period from 2018-20. Darker shades

indicate lower RR citation rates; larger circles indicate lower proportion of Harm (G+) citations. See Figure 18 for info on Alaska,

Hawaii, and Puerto Rico.

Long Term Care Community Coalition

39

Figure 7: Resident Rights (F550) citation rate and severity by state (2018-20).

Long Term Care Community Coalition

41

Staffing

Introduction

• Numerous studies have shown that nursing homes with higher staffing levels are better

equipped to meet their residents’ care needs. To ensure that residents receive good care and

are safe, the federal nursing home requirements mandate that facilities have sufficient staff,

with the appropriate competencies, to meet the clinical, emotional, and psycho-social

needs of every resident admitted and retained in the facility.

34

• Nevertheless, understaffing is a widespread and persistent problem in nursing homes

nationwide. This understaffing has serious repercussions for residents. As one study noted,

“[f]unctional ability, pressure ulcers, and weight loss are the most sensitive quality indicators

linked to staffing.”

35

• LTCCC’s quarterly reports on staffing in U.S. nursing homes

36

-- including a report on the first

quarter of 2021 — consistently find that most U.S. nursing homes are understaffed and fail to

meet the necessary threshold for total care staff (4.10 HPRD) as determined by a 2001

landmark federal study.

37

The 2001 study determined that 91% of facilities lacked sufficient

staff to provide decent care.

• Though nursing home industry lobbyists have

long argued that inadequate staffing is due to

insufficient funding, there are no reliable data to

support that claim. In fact, an increasing

percentage of nursing homes are operated by

for-profit companies, including profit-oriented

Real Estate Investment Trusts and Private Equity

firms. Importantly, a 2014 federal study found

that an astonishing one-third of the people who

go to nursing homes for Medicare rehab services

(which even nursing homes acknowledge are

highly profitable) are harmed within an average

of 15.5 days after entering the facility. That study

34

For more information, see LTCCC’s Fact Sheet: Requirements for Nursing Home Care Staff & Administration,

available at https://nursinghome411.org/fact-sheet-requirements-for-nursing-home-care-staff-administration/.

35

Bostick JE, Rantz MJ, Flesner MK, Riggs CJ, “Systematic review of studies of staffing and quality in nursing

homes,” J Am Med Dir Assoc. (Jul 2006). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16843237/

36

Available at https://nursinghome411.org/data/staffing/.

37

Abt Associates (Prepared for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services), Appropriateness of Minimum

Nurse Staffing Ratios in Nursing Homes, Report to Congress: Phase II Final (December 2001). Available at

https://theconsumervoice.org/uploads/files/issues/CMS-Staffing-Study-Phase-II.pdf.

‘It can be frightening’: A “No

Harm” Sufficient Staffing

Deficiency (F725)

A Michigan nursing home failed to

provide timely call light response

and adequate staffing to provide

care for 14 residents. “For the last

couple weeks there has only been

two people at night,” a resident

said. “I have had a [medical

condition]. It can be frightening.”

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

found that 59% of the time that harm is “clearly or likely preventable.”

38

In short,

reimbursement rates are not an accurate (or appropriate) excuse for insufficient staffing.

• This section contains state and regional data on staffing levels and Sufficient Nursing Staff (SS)

citations (F725), including key findings, a map data visualization, and tables.

Key Findings

• Though long recognized as one of the most serious and widespread problems in the nursing

home sector, sufficient staffing (SS) is rarely cited. Nationwide, SS citations totaled just 2,625

in the three-year period from 2018-20.

• State totals for SS citations ranged from 0 (DC and Puerto Rico) to 338 (Michigan) for the

three-year period. The median SS citation total was 24 (eight citations per state per year).

• Correlation analysis showed a positive association between staffing citation rates and staffing

levels. For example: Region 10 had the highest annual SS citation rate (2.4 per 1k residents)

and highest staffing ratio (4.30 Total Nurse Staff HPRD). Conversely, Region 2 had the lowest

annual SS citation rate (0.13 per 1,000 residents) and ranked ninth (out of 10 regions) in

staffing ratio (3.39 Total Nurse Staff HPRD). (See Figure 21).

• Though staffing is universally recognized as essential for resident safety and dignity, the

identification of resident harm or immediate jeopardy due to insufficient staffing is

extremely rare (a total of 105 G+ citations in three years) and unevenly distributed across

both the states and CMS Regions.

• Regions 1, 2, 3, and 7 reported a combined four G+ citations, with Region 2 surveyors

identifying zero (0) cases in which a resident was harmed or put in immediate jeopardy due to

inadequate staffing in the entire three-year period (see Figure 22).

• Given that it is extremely unlikely for a facility to be penalized without resident harm

identified, the dearth of G+ SS citations demonstrates a system-wide and persistent failure to

hold nursing homes accountable for the most basic of requirements. The lack of meaningful

enforcement of federal staffing requirements raises the question: Whose interests are the

state survey agencies working to protect – those of residents and families or those of the

nursing home industry?

38

Adverse Events in Skilled Nursing Facilities: National Incidence Among Medicare Beneficiaries (Feb. 2014).

Long Term Care Community Coalition

43

Data: Map and Tables

Staffing Citation Rate and Severity by State (2018-20)

Figure 20: Annual Sufficient Staffing citations (F725) per resident during the three-year period from 2018-20. Darker shades

indicate lower citation rates; larger circles indicate lower proportion of Harm (G+) citations. See Figure 21 for info on Alaska,

Hawaii, and Puerto Rico.

Staffing Data Notes

Staff HPRD (Hours Per Resident Day) is a staffing metric calculated by dividing a nursing home's daily staff

hours by its MDS census. (A nursing home averaging 300 total nurse staff hours & 100 residents per day would

have a 3.0 Total Nurse Staff HPRD (300/100 = 3.0)).

Total Nurse Staff combines hours from RNs (incl. Admin and DON), LPNs (incl. Admin), CNAs, Med Aide/Tech,

and NA in Training (NA TR). Total RN Staff combines hours from RNs (incl. Admin and DON).

A landmark 2001 federal study found that residents need 4.10 hours total care staff HPRD and 0.75 RN HPRD

to ensure they receive sufficient clinical care. Staffing averages for most states and regions fall below those

thresholds.

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

Figure 9: Sufficient Staffing (F725) citation rate and severity by state (2018-20). The last four columns provide state-level data

on average total nurse staffing, RN staffing, and state rankings for each, based on payroll-based journal data from Q4 2019.

Long Term Care Community Coalition

45

Interactive charts and maps are available at https://nursinghome411.org/survey-data-report/.

Figure 22: Sufficient staffing (F725) citation rate/severity and staffing levels, by region (2018-20). The last four columns provide

state-level data on average total nurse staffing, RN staffing, and state rankings for each, based on payroll-based journal data

from Q4 2019.

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

Fines

Introduction

• Fines, also known as Civil Monetary Penalties (CMPs), are a

critical tool for holding nursing homes accountable for

substandard care, abuse, and neglect. Fundamentally, when

substandard care is identified, the imposition of a fine

imposes a cost for the failure to meet the standards which

nursing homes voluntarily agree to meet or exceed.

• Conversely, when a fine (or other penalty) is not imposed for

substandard care, it sends a message to the facility (and

industry as a whole) that poor care is acceptable. This is of

special concern when substandard care harms residents or

puts them in jeopardy.

• This section contains state and regional data on frequency

(adjusted for resident population) and severity of fines,

including key findings, a map data visualization, and tables.

Key Findings

• Unfortunately, as these data indicate, nursing homes infrequently face financial penalties

when they fail to meet minimum standards. From a consumer perspective, the absence of a

financial incentive makes it unlikely that poorly performing nursing homes will change their

practices.

• Nationwide, with over 15,000 nursing homes serving over one million residents on any given

day, federal data indicate an average of 2,126 fines per year are imposed. This is the

equivalent of 1.6 fines per 1,000 nursing home residents.

• The average fine was $29,000 while the median fine was $11,700.

• Fine frequency and severity varied significantly by state and region.

• Comparing states, Montana had the highest amount in annual fines per resident ($206) while

Nevada had the lowest ($3). The median state annual fine per resident was $46.

• The average annual fine per resident in Region 10 ($120) was 10 times higher than the

average fine per resident in Region 2 ($12).

• Note: This report only includes fines reported in the federal database, which does not include

fines that are imposed by individual states. For information on state fines, consult the

individual state’s website.

As the data in this

report indicate, there is

often little or no

punishment when

nursing homes fail to

provide care that

meets the standards

they are paid to

achieve, even when

such failures result in

significant suffering.

Long Term Care Community Coalition

47

Data: Map and Tables

Annual Fine Amount ($) and Frequency by State (2018-20)

Figure 23: Fines during the three-year period from 2018-20. Darker shades indicate lower amount in fines ($) per resident;

larger circles indicate lower number of fines per resident. See Figure 24 for info on Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico.

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

Figure 10: Fine rates and severity by state (2018-20).

Broken Promises: An Assessment of Federal Data on Nursing Home Oversight

III. Discussion & Recommendations

Discussion: A Failure to Enforce

The results of this study indicate that, in the years leading into the COVID-19 pandemic and the

first year of the pandemic, the state and federal response to longstanding and often serious

problems in nursing homes was, overall, very weak. The failure to vigorously enforce the range

of minimum standards we reviewed – from basic