COVID-19 IN

NURSING HOMES

CMS Needs to

Continue to

Strengthen Oversight

of Infection Prevention

and Control

Report to Congressional Addressees

September 2022

GAO-22-105133

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-22-105133, a report to

congressional a

ddressees

September 2022

COVID-19 IN NURSING HOMES

CMS

Needs to Continue to Strengthen Oversight of

Infection

Prevention and Control

What GAO Found

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is responsible for ensuring

that nursing homes meet federal standards. CMS enters into agreements with

state survey agencies to conduct surveys and investigations of the state’s

nursing homes. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issues

guidance, operates surveillance systems, and provides technical assistance to

support infection prevention and control in nursing homes.

GAO analysis of CMS data reported by nursing homes shows that seven of the

eight key indicators of nursing home resident mental and physical health

worsened at least slightly the first year of the pandemic (2020), compared to the

years prior to the pandemic. See the figure below for examples of two outcomes

we reviewed.

Percentage of Residents Who Experienced Depression and Unexplained Weight Loss, by Year

CMS and CDC took actions on infection prevention and control prior to and

during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, prior to the pandemic, CMS

required nursing homes to designate an infection preventionist on staff. This

person is a trained employee responsible for the home’s infection prevention and

control program and was crucial to nursing homes during the pandemic. CMS

also made changes in how nursing homes were surveyed during the pandemic.

However, GAO found areas where CMS could take additional actions, including:

• Strengthening oversight of the infection preventionist role. GAO identified

ways CMS could strengthen oversight of the infection preventionist role, such

as by establishing minimum training standards. CMS could also collect

infection preventionist staffing data and use it to determine whether the current

infection preventionist staffing requirement is sufficient.

• Strengthening infection prevention and control guidance. GAO identified

how CMS could strengthen this guidance by providing information to help

surveyors assess the scope and severity of infection prevention and control

deficiencies they identify. For example, CMS could add COVID-19-relevant

examples for scope and severity classifications to its State Operations

Manual—the key guidance state survey agencies use for conducting nursing

home surveys.

View GAO-22-105133. For more information,

contact

John Dicken at (202) 512-7114 or

.

Why GAO Did This Study

Implementing proper infection

prevention and

control practices can

be critical for preventing the spread of

infectious diseases.

Infection

prevention and control

has been a

long

-standing concern in the nation’s

more than 15,000 nursing homes

—

one

that the COVID

-19 pandemic has

brought into sharper focus.

Some

infection prevention and control

practices in nursing h

omes, such as

social isolation,

may negatively affect

resident mental and physical health.

The CARES Act

directs GAO to

monitor the federal pandemic

response. GAO was also asked to

review

federal oversight of nursing

homes in light of the pandemic. Among

other objectives, this report: (1)

describes

what data reveal about any

changes in resident health

before and

during the pandemic and (2)

examines

infection prevention and control actions

CMS and CDC have

taken in nursing

homes before and

during the

pandemic.

GAO

(1) reviewed CMS and CDC

documents

, (2) analyzed CMS

resident

health

data from 2018 through 2021,

and

(3) interviewed CMS, CDC, state

survey agency,

and nursing home

officials

in a non-generalizable sample

of eight

states selected for variation in

factors such as geographic location.

What GAO

Recommends

GAO is making

three

recommendations to

CMS related to

the role of the infection preventionist

and

clarifying infection prevention and

control

guidance. HHS agree

d with our

first recommendation

, but neither

agreed nor disagreed with our other

two

recommendations.

Page i GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

Letter 1

Background 6

Some Indicators of Resident Mental and Physical Health

Worsened during the COVID-19 Pandemic 10

Infection Prevention and Control Deficiencies Persisted in Nursing

Homes during the COVID-19 Pandemic 15

CMS and CDC Took Actions to Strengthen Infection Prevention

and Control but Should Do More 21

Conclusions 33

Recommendations for Executive Action 33

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 34

Appendix I Related GAO Products on COVID-19 in Nursing Homes 38

Appendix II Examples of Infection Prevention and Control Deficiencies Cited

in Nursing Homes during the Pandemic 39

Appendix III Types of Surveys and Investigations to Assess Whether

Nursing Homes Are Meeting Federal Standards 40

Appendix IV Number and Percentage of Surveyed Nursing Homes with Infection

Prevention and Control (IPC) Deficiencies 44

Appendix V Federal Nursing Home Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) Actions 45

Appendix VI Comments from the Department of Health and Human Services 49

Appendix VII GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 55

Contents

Page ii GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

Tables

Table 1: Selected Federal Infection Prevention and Control (IPC)

Actions and Examples of Stakeholder-Reported

Perspectives on Advantages and Disadvantages 26

Table 2: Illustrative Examples of Narratives from Infection

Prevention and Control Deficiencies Cited in Nursing

Homes during the Pandemic 39

Table 3: Number and Percentage of Surveyed Nursing Homes

with Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) Deficiencies,

by Calendar Year and Deficiency Code 44

Table 4: Nursing Home Infection Prevention and Control (IPC)

Actions Taken by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services (CMS) and the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC) 45

Figures

Figure 1: Percentage of Long-Stay Nursing Home Residents Who

Experienced Selected Mental Health Indicators, by Year 11

Figure 2: Percentage of Long-Stay Nursing Home Residents Who

Experienced Selected Physical Health Indicators, by Year 12

Figure 3: Type of Survey or Investigation Used by State Survey

Agencies to Identify Infection Prevention and Control

Deficiencies, 2018 through 2021 17

Figure 4: Types of Surveys and Investigations Used by State

Survey Agencies to Assess Whether Nursing Homes Are

Meeting Federal Standards, as of April 2022 42

Page iii GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

Abbreviations

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

IPC Infection Prevention and Control

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

September 14, 2022

Congressional Addressees

Infection prevention and control (IPC) has been a long-standing concern

in the nation’s more than 15,000 Medicare- and Medicaid-certified nursing

homes—one the COVID-19 pandemic has brought into sharper focus.

1

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, infections were a leading cause of

death and hospitalization among nursing home residents, with estimates

of up to 380,000 residents dying each year.

2

Since that time, COVID-19

has emerged as a new and highly contagious respiratory disease that has

had devastating consequences for the nation’s more than one million

nursing home residents, including high rates of severe illness and death.

COVID-19 has also substantially affected the broader nursing home

industry, including nursing home staff. The initial unknown nature of the

virus that causes COVID-19 and the scope of the pandemic also created

unprecedented challenges for state and federal agencies that work to

ensure the quality of care delivered in nursing homes and to protect

public health.

3

In our previous reporting, we found that, in the years prior to the

pandemic, nursing homes had persistent and widespread challenges with

IPC.

4

For example, we found that implementing proper IPC practices,

such as isolating infected residents, can be critical for preventing the

spread of infectious diseases, including COVID-19—thus protecting both

resident and staff health and well-being. However, some IPC practices in

1

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, IPC protects patients,

residents, healthcare personnel, and visitors by preventing healthcare-associated

infections and limiting the spread of pathogens through the implementation of evidence-

based interventions.

2

Department of Health and Human Services, The National Action Plan to Prevent Health

Care-Associated Infections: Road Map to Elimination (Washington, D.C.: 2013).

3

As GAO has previously reported, during the COVID-19 pandemic, nursing homes

experienced high staff cases and deaths and challenges related to staffing, personal

protective equipment, and testing. See, for example, GAO, COVID-19: Federal Efforts

Could Be Strengthened by Timely and Concerted Actions, GAO-20-701 (Washington,

D.C.: Sept. 21, 2020).

4

GAO, Infection Control Deficiencies Were Widespread and Persistent in Nursing Homes

Prior to COVID-19 Pandemic, GAO-20-576R (Washington, D.C.: May 20, 2020).

Letter

Page 2 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

nursing homes, such as social isolation, may negatively affect resident

mental and physical health.

5

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), primarily through

the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), has led the response to the

COVID-19 pandemic in nursing homes. CMS is the federal oversight

agency responsible for ensuring that nursing homes meet federal quality

standards to be eligible to participate in the Medicare and Medicaid

programs. These standards require, for example, that nursing homes

establish and maintain an IPC program. To monitor compliance with

these standards, CMS enters into agreements with state survey agencies

in each state government and oversees the work the state survey

agencies do. CDC issues guidance with recommendations for preventing

and managing infectious diseases, operates infectious disease

surveillance systems, and provides technical assistance through

programs aimed at supporting and assessing IPC in nursing homes, and

tracking IPC data.

The CARES Act includes a provision directing us to monitor the federal

response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

6

Further, you also asked us to

examine federal oversight of IPC protocols and the adequacy of

emergency preparedness standards for emerging infectious diseases in

nursing homes, as well as CMS’s response to the pandemic. Since 2020,

we have examined the response to COVID-19 in nursing homes in

multiple studies. Some studies have been completed and released and

others are ongoing. (See app. I for a list of completed related reports.)

In this report, we: (1) describe what data reveal about any changes in

resident mental and physical health before and during the COVID-19

pandemic, (2) describe whether IPC challenges have persisted in nursing

homes during the pandemic, and (3) examine the IPC actions that CMS

5

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Social Isolation and

Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System (Washington, D.C.:

The National Academies Press, 2020).

6

Pub. L. No. 116-136, § 19010(b), 134 Stat. 281, 580 (2020). Throughout the pandemic,

we regularly issued government-wide reports on the federal response to COVID-19. All

government-wide reports are available on GAO’s website at

https://www.gao.gov/coronavirus.

Page 3 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

and CDC have taken related to nursing homes before and during the

pandemic.

To describe what data reveal about any changes in resident mental and

physical health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, we analyzed

2018 through 2021 CMS Minimum Data Set resident assessment data.

7

We compared selected health indicators across calendar years for all

long-stay residents who had lived in the nursing home greater than 100

days.

8

We selected four mental and four physical health indicators to

analyze based on indicators highlighted in our review of relevant literature

and during conversations with knowledgeable stakeholders.

9

Then, using

each resident’s calendar year assessments, we determined the

percentage of residents experiencing each selected health indicator.

10

We

analyzed the data in the CMS Minimum Data Set as they were reported

by nursing homes to CMS. We did not otherwise independently verify the

accuracy of the information with these nursing homes. We assessed the

reliability of the dataset by checking for missing values and obvious

errors, reviewing relevant CMS documents, and reviewing other studies

7

2021 was the most recent calendar year available at the time of our analysis.

The CMS Minimum Data Set is reported by nursing homes, which are required to

complete resident assessments at regular intervals as part of federal requirements to

participate in the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Nursing homes are required to

conduct resident assessments at entry, quarterly, at discharge, and if there are any

significant changes or corrections. During standard surveys, surveyors can evaluate

whether a nursing home’s assessments meet federal standards for accuracy.

8

The same resident may have lived in the home for multiple years and would therefore be

present in each calendar year. Most nursing homes provide both long-term residential and

short-term rehabilitative care.

According to CMS, the number of nursing home residents declined sharply during the

pandemic.

9

For example, see M. Levere, P. Rowan, A. Wysocki, “The Adverse Effects of the COVID-

19 Pandemic on Nursing Home Resident Well-Being,” JAMDA, vol. 22, no. 5 (2021): 948-

954 and L. Fleisher et al., “Health Care Safety During the Pandemic and Beyond—

Building a System That Ensures Resilience,” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol.

386, no. 7 (2022): 609-611.

10

The mental health indicators we selected and analyzed included whether, on any

assessment in a given calendar year, a resident had any symptoms of depression or took

anti-depressant, anti-psychotic, or anti-anxiety medications. The physical health indicators

we selected and analyzed included whether, on any assessment in a given calendar year,

a resident experienced at least one fall, unexplained weight loss, urinary incontinence

ranging from occasionally incontinent to always incontinent, or at least one or more stage

1 or higher unhealed pressure ulcers.

Page 4 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

that used these data and identified some limitations of our analysis.

11

Based on this review, we determined the data were sufficiently reliable for

the purposes of this reporting objective. We also conducted interviews

with officials from a non-generalizable sample of nine selected nursing

homes in eight selected states: Arkansas, California, Florida, Maryland,

Michigan, Montana, Rhode Island, and Washington.

12

These states were

selected based on three criteria: (1) geographic location; (2) number of

nursing home beds; and (3) number of nursing home residents and staff

with confirmed positive cases of COVID-19.

13

We then selected nursing

homes to obtain variation in factors such as bed count and profit or not-

for-profit status. We asked nursing home officials to describe resident

mental and physical health during the pandemic. Additionally, we

interviewed national associations, including the American Health Care

Association and National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care,

about these issues.

To describe whether IPC challenges have persisted in nursing homes

during the pandemic, we analyzed CMS data on nursing home

deficiencies cited by state surveyors in all 50 states and Washington,

11

Some studies have found that the Minimum Data Set data reported by nursing homes

underreports anti-psychotic use and falls. Therefore, it is possible that our analysis also

underreports these health indicators. For examples, see HHS Office of Inspector General,

CMS Could Improve the Data It Uses to Monitor Antipsychotic Drugs in Nursing Homes,

OEI-07-19-00490 (Washington, D.C.: May 3, 2021) and J. Mintz et al., “Validation of the

Minimum Data Set Items on Falls and Injury in Two Long-Stay Facilities,” Journal of the

American Geriatrics Society, vol. 69, no. 4 (April 2021). Unless the rate of underreporting

changed during the pandemic, the analysis of change over time would still likely be

broadly valid.

In addition, as the pandemic progressed, it is possible that nursing homes had to delay

submitting their resident assessments if, for example, they were responding to a COVID-

19 outbreak. In March 2020, CMS waived the timeframe requirements for nursing homes

to complete and transmit resident assessments in order to allow nursing homes to focus

on infection control efforts. However, these timeframes were re-instated by CMS in April

2021. According to CMS, the majority of nursing homes were completing and transmitting

their assessments in a timely fashion. This is consistent with our analysis, where we

determined that less than 10 percent of nursing home quarterly assessments were

delayed in each year of our review. See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services,

Updates to Long-Term Care Emergency Regulatory Waivers Issued in Response to

COVID-19, QSO-21-17-NH (Baltimore, Md.: April 8, 2021).

12

In Washington State, we interviewed officials from two nursing homes, while in the other

states, we interviewed officials from one home in each state.

13

COVID-19 case rates were for the week ending May 16, 2021.

Page 5 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

D.C., from 2018 through 2021.

14

Using these data, we analyzed the

deficiency codes used by state surveyors when a nursing home fails to

meet CMS’s requirements for IPC. We also used CMS’s Quality,

Certification, and Oversight Reports website to obtain high-level summary

data on the percentage of nursing homes with an overdue standard

survey.

15

We assessed the reliability of these datasets by checking for

missing values and obvious errors and reviewing relevant CMS

documents and determined the data were sufficiently reliable for the

purposes of this reporting objective. We also conducted interviews with

state survey agency officials and nursing home officials in the non-

generalizable sample of eight states described above. We asked

interviewees to describe the extent to which IPC challenges persisted in

nursing homes and how they have responded.

To examine the IPC actions that CMS and CDC have taken related to

nursing homes before and during the pandemic, we reviewed CMS and

CDC regulations and guidance. We also interviewed officials at CMS and

CDC and officials from state survey agencies and nine nursing homes in

the non-generalizable sample of eight states described above, as well as

officials from the national associations with knowledge of nursing home

issues previously noted. We determined that the control environment

component of internal control was significant to this objective, along with

the underlying principle that management should establish expectations

of competence for key roles. We also determined that the risk

assessment component of internal control was significant to this

objective, along with the underlying principle that management should

define objectives clearly to enable the identification of risks and define

risk tolerances. Finally, we determined that the information and

communication component of internal control was significant to this

objective, along with the underlying principle that management should

use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives. We assessed

CMS’s oversight activities implemented leading up to and during the

COVID-19 pandemic in the context of these internal control principles, as

well as HHS statutory requirements, CMS regulatory requirements for

14

2021 was the most recent calendar year available at the time of our analysis.

In addition, we used the CMS Care Compare Inspection Date files, which were accessed

on March 28, 2022 from https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/dataset/svdt-c123.

15

CMS’s Quality, Certification, and Oversight Reports system is a website that provides

summary-level data reports on nursing homes. This system is available at

https://qcor.cms.gov and was accessed on April 7, 2022.

Page 6 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

nursing home participation in Medicare and Medicaid programs, and

CMS’s State Operations Manual, to determine whether these oversight

actions were clearly defined and understood to enable nursing homes

and state survey agencies to address the risk posed by COVID-19; and

whether the agency has access to quality information about whether its

oversight actions were achieving their stated objectives.

16

We conducted this performance audit from April 2021 to September 2022

in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Federal law requires nursing homes to keep residents safe from

infectious diseases by establishing and maintaining an IPC program

designed to help prevent the development and transmission of

communicable diseases and infections.

17

Even before COVID-19, nursing home residents were at a high risk for

several different types of infections, including respiratory infections,

gastroenteritis, skin and soft tissue infections, and urinary tract infections.

Nursing home residents can be particularly susceptible to infections

because of their advanced age and higher risk of comorbidities.

18

Further,

nursing home residents are increasingly requiring more medically

complex care and are therefore more susceptible to infection. For

example, residents discharged from the hospital back to the nursing

16

Federal law establishes minimum requirements nursing homes must meet to participate

in the Medicare and Medicaid programs, and designates the HHS Secretary as

responsible to ensure that requirements governing the provision of care in nursing homes,

and the enforcement of such requirements, are adequate to protect the health, safety,

welfare, and rights of residents and promote the effective and efficient use of public

moneys. 42 U.S.C. §§ 1395i-3(f)(1),1396r(f)(1); 42 C.F.R. §§ 483.1--483.95 (2021).

GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO-14-704G

(Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014). Internal control is a process effected by an entity’s

oversight body, management, and other personnel that provides reasonable assurance

that the objectives of an entity will be achieved.

17

42 U.S.C. §§ 1395i-3(d)(3)(A), 1396r(d)(3)(A); 42 C.F.R. § 483.80 (2021).

18

Comorbidity refers to the presence of more than one distinct disease in a person at the

same time.

Background

Infections in Nursing

Homes

Page 7 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

home can bring infections into the home. They may also require a high-

degree of clinical monitoring in order to identify and prevent infection and

to help prevent the spread of resistant pathogens between residents. In

addition, while nursing homes create important social opportunities for

residents through communal dining and recreational spaces, these

shared spaces can increase the transmission risk for infectious diseases,

especially viruses causing respiratory or gastrointestinal outbreaks.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to high rates of infection and death in

nursing home residents and staff. Nursing home residents are at

increased risk because older adults and those with underlying health

conditions have a high mortality rate when infected with the virus,

according to CDC.

19

In addition, the congregate nature of nursing

homes—with staff caring for multiple residents and residents sharing

rooms and other communal spaces—can increase the risk that COVID-19

will enter the home and easily spread.

20

The introduction of COVID-19

vaccines in December 2020 resulted in a sharp decline in nursing home

cases and deaths through the first part of 2021; however, cases and

deaths began to increase again with the emergence of more highly

transmissible virus variants during the summer of 2021, coinciding with

the emergence of the Delta variant, and again in winter 2022, coinciding

with the emergence of the Omicron variant.

Federal laws establish minimum requirements nursing homes must meet

to participate in the Medicare and Medicaid programs, including

standards for the quality of care.

21

Primarily through its State Operations

Manual, CMS establishes the responsibilities of state survey agencies in

ensuring that these federal quality standards for nursing homes are met,

19

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19: People Who Live in a Nursing

Home or Long-Term Care Facility, accessed on May 7, 2022,

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-in-nursing-ho

mes.html.

20

According to CDC, COVID-19 is spread in three main ways: (1) breathing in small

droplets or particles exhaled by an infected person (2) having these small droplets and

particles land on the eyes, nose, or mouth, especially through a cough or a sneeze (3)

touching eyes, nose, or mouth with hands that have the virus on them. See Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention, How COVID-19 Spreads, accessed on April 16, 2022,

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/how-covid-spreads.html.

21

42 U.S.C. §§ 1395i-3, 1396r; 42 C.F.R. §§ 483.1--483.95 (2021). Federal statutes and

their implementing regulations use the terms “skilled nursing facility” (Medicare) and

“nursing facility” (Medicaid). For the purposes of this report, we use the term nursing home

to refer to both skilled nursing facilities and nursing facilities.

Federal Oversight of

Nursing Homes

Page 8 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

such as that nursing homes establish and maintain an IPC program.

22

To

monitor compliance with these standards, CMS enters into agreements

with state survey agencies in each state to assess whether nursing

homes meet CMS’s standards. Prior to the pandemic, state surveyors

from the state survey agencies were responsible for assessing nursing

homes using (1) recurring comprehensive standard surveys, or (2) as-

needed investigations for complaints from the public and facility-reported

incidents.

• Standard surveys. State survey agencies are required by federal law

to perform unannounced, on-site standard surveys of every nursing

home receiving Medicare or Medicaid payment at least every 15

months, with a statewide average frequency of every 12 months.

23

Standard surveys are important for protecting nursing home residents

because they serve as a comprehensive assessment of the safety

and quality of nursing home care across several areas including food

and nutrition, resident rights, physician and nursing services, and the

physical environment.

• Investigations. In addition to performing standard surveys, state

survey agencies are required by federal law to investigate all

complaints of nursing home violations of requirements.

24

These fall

into two categories: (1) complaints submitted by residents, family

members, friends, physicians, and nursing home staff; and (2)

“facility-reported incidents” that are self-reported by the nursing

homes. These investigations offer the state survey agency a unique

opportunity to identify and correct care problems, as they can provide

a timely alert of acute issues that otherwise might not be addressed

until a standard survey takes place.

If a surveyor from a state survey agency determines that a nursing home

violated a federal standard during a survey or investigation, the nursing

22

At a minimum, nursing homes must (1) have a system to prevent, identify, report,

investigate, and control infections and communicable diseases for all residents, staff,

volunteers, visitors, and others providing services in the home; (2) have written standards,

policies, and procedures for their infection prevention and control program; (3) have

antibiotic use protocols and a system to monitor antibiotic use; and (4) have a system for

recording incidents identified under the home’s infection prevention and control program

and any corrective actions taken. 42 C.F.R. § 483.80(a)(1)-(4) (2021).

23

42 U.S.C. §§ 1395i-3(g)(1)(A), (g)(2)(A)(iii), 1396r(g)(1)(A), (g)(2)(A)(iii); 42 C.F.R. §

488.308(a)-(b) (2021).

24

42 U.S.C. §§ 1395i-3(g)(4), 1396r(g)(4); 42 C.F.R. § 488.332(a) (2021).

Page 9 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

home is cited for the deficiency using a specific deficiency code (referred

to as an F-tag). Cited deficiencies are then classified into categories

according to scope (the number of residents potentially affected) and

severity (the potential for or occurrence of harm to residents). For most

cited deficiencies, nursing homes are required to submit a plan of

correction that addresses how the home plans to correct the

noncompliance and implement systemic change to ensure the deficient

practice would not recur.

25

In addition, when nursing homes are cited with

deficiencies, federal enforcement actions can be implemented to

encourage homes to make corrections.

26

In general, for deficiencies with

a higher scope and severity, CMS may implement the enforcement action

immediately.

27

For other deficiencies with a lower scope and severity, the

nursing home may be given an opportunity to correct the deficiencies,

which, if corrected before the scheduled effective date, can result in the

planned enforcement action not being implemented.

In 2016, CMS finalized a comprehensive update to its nursing home

standards.

28

The update included new requirements and aligned existing

requirements with current clinical practices. These standards covered a

variety of categories, such as quality of care and IPC.

We have issued several reports examining COVID-19 in nursing homes,

part of our larger bodies of work on nursing home oversight and on the

federal response to the COVID-19 pandemic (see app. I.) For example, in

May 2020, we analyzed CMS deficiency data and found that most nursing

25

The plan of correction serves as the nursing home’s allegation of compliance.

Depending on the severity of the deficiency cited, surveyors revisit the nursing home to

ensure that the home actually implemented its plan and corrected the deficiency.

26

CMS does not require enforcement actions be implemented for all deficiencies.

Enforcement actions include, but are not limited to, directed in-service training, fines

known as civil money penalties, denial of payment, and termination from the Medicare and

Medicaid programs.

27

The scope and severity of a deficiency is one of the factors that CMS may take into

account when implementing enforcement actions. CMS may also consider a nursing

home’s prior compliance history, desired corrective action and long-term compliance, and

the number and severity of all the nursing home’s deficiencies.

28

Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Reform of Requirements for Long-Term Care

Facilities, 81 Fed. Reg. 68,688 (Oct. 4, 2016). Phase 1 (effective November 28, 2016)

implemented most minor modifications to the existing nursing home regulations; phase 2

(effective November 28, 2017) implemented new regulations and re-structured CMS’s

deficiency code system; and phase 3 (effective November 28, 2019) implemented the

remaining requirements.

Prior GAO Work

Page 10 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

homes were cited for IPC deficiencies, such as failure to use proper hand

hygiene, in the years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

29

In addition,

during the COVID-19 pandemic, most nursing homes had multiple

outbreaks and weeks of sustained COVID-19 transmission from May

2020 through January 2021.

30

In response to the CARES Act, we have

examined the federal response to COVID-19 in nursing homes in multiple

reports, where we reported on nursing home-related actions HHS had

taken in response to the pandemic, as well as challenges nursing homes

faced responding to COVID-19.

Our analysis of CMS data shows that seven of the eight key indicators of

nursing home resident mental and physical health that we reviewed

worsened at least slightly in 2020, the first year of the pandemic,

compared to the years prior to the pandemic.

31

Six of these key indicators

continued to be worse in the second year of the pandemic than in the

years prior to the pandemic.

32

For example, the percentage of residents

who experienced depression was 58.7 percent in 2018, 63.9 percent in

2020, and 61.5 percent in 2021. Similarly, the percentage of residents

who experienced unexplained weight loss was 14.8 percent in 2018, 19.3

percent in 2020, and 17.4 percent in 2021. (See figures 1 and 2.)

29

See GAO-20-576R.

30

GAO, COVID-19 in Nursing Homes: Most Homes Had Multiple Outbreaks and Weeks of

Sustained Transmission from May 2020 through January 2021, GAO-21-367

(Washington, D.C.: May 19, 2021).

31

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been concerns about mental health in the

general population. For example, in January 2021, four in 10 U.S. adults reported

symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder, up from one in 10 in 2019. See N. Panchal,

R. Kamal, C. Cox, and R. Garfield, The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and

Substance Abuse (San Francisco, Calif.: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2021).

32

We observed a large decrease (44 percent) in the number of long-stay nursing home

residents between 2018 and 2021 (from about 1.9 million to 1.0 million). CMS officials

indicated that they also observed a sharp decline in the number of nursing home residents

during the pandemic. It is likely that more residents left nursing homes or passed away

during the pandemic, either due to COVID-19 or other factors, compared to prior years. It

is unclear whether the residents who remained in nursing homes during the pandemic in

2020 and 2021 had different health issues than residents who lived in nursing homes prior

to the pandemic.

Some Indicators of

Resident Mental and

Physical Health

Worsened during the

COVID-19 Pandemic

Page 11 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

Figure 1: Percentage of Long-Stay Nursing Home Residents Who Experienced

Selected Mental Health Indicators, by Year

Notes: Long-stay residents are those living in a nursing home for greater than 100 days. The data in

the Minimum Data Set are self-reported to CMS by nursing homes. “Experienced depression”

indicates whether a resident had any symptoms of depression on any assessment in a given calendar

year. “Took anti-depressant medications,” “took anti-psychotic medications,” and “took anti-anxiety

medications” indicates if, on any assessment in a given calendar year, a resident took anti-

depressant, anti-psychotic, or anti-anxiety medications in the prior 7 days before the assessment or, if

less than 7 days, since admission.

Page 12 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

Figure 2: Percentage of Long-Stay Nursing Home Residents Who Experienced

Selected Physical Health Indicators, by Year

Notes: Long-stay residents are those living in a nursing home for greater than 100 days. The data in

the Minimum Data Set are self-reported to CMS by nursing homes. “Experienced at least one fall”

indicates if, on any assessment in a given calendar year, a resident experienced at least one fall

since the prior assessment or since admission, whichever was more recent. “Experienced

unexplained weight loss” indicates if, on any assessment in a given calendar year, a resident

experienced weight loss of 5 percent or more in the last month or 10 percent or more in the last six

months. “Experienced incontinence” indicates if, on any assessment in a given calendar year, a

resident experienced urinary incontinence ranging from occasionally incontinent to always

incontinent. “Experienced at least one pressure ulcer” indicates if, on any assessment in a given

calendar year, a resident had at least one or more stage 1 or higher unhealed pressure ulcers.

Page 13 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

The results of our data analysis were supported by our interviews with

nursing home officials in selected states, who told us they observed

worsening resident mental and physical health during the COVID-19

pandemic. Specifically, for resident mental health, officials from some

nursing homes we interviewed told us they observed more residents who

experienced depression, as well as more residents who took anti-

psychotic medication. Nursing home officials and national organizations

we interviewed attributed this in part to the isolation residents felt from the

limitations CMS placed on visitation or group activities in nursing homes

during the pandemic to limit the transmission of COVID-19. CMS initially

restricted visitation and suspended group activities in March 2020. After

the initial restrictions, CMS made changes to its guidance multiple times

during the pandemic to allow for more visitation and group activities, while

identifying some situations where limitations would be appropriate to help

prevent COVID-19 infections. In November 2021, all visitation limitations

were fully lifted.

33

According to CDC, these restrictions were intended to

help limit transmission of COVID-19 early in the pandemic, when nursing

homes faced multiple complex challenges, including: understanding a

novel virus, inability to test to detect asymptomatic infected individuals,

variable personal protective equipment supply access, staffing shortages

that made controlled visitation more difficult, increasing cases across the

country with few effective treatments available, and no vaccine

availability.

Nursing home officials in our selected states also told us that they

observed worsening resident physical health during the COVID-19

pandemic. Officials from some of the nursing homes we interviewed told

us they observed more residents who experienced weight loss and falls

when visitation and group activities were limited. One factor contributing

to unintended weight loss by residents may have been that, prior to the

pandemic, visitors assisted some residents with eating. Officials from one

nursing home said that these residents did not eat as well when being fed

by a busy staff member rather than an attentive visitor and thus lost

33

These restrictions began in March 2020, were changed in September 2020, March

2021, and April 2021, and were fully lifted for all residents in November 2021. See Centers

for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Guidance for Infection Control and Prevention of

COVID-19 in Nursing Homes, QSO-20-14-NH (Baltimore, Md.: March 13, 2020) and

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Nursing Home Visitation – COVID-19, QSO-

20-39-NH (Baltimore, Md.: Sept. 17, 2020), revised March 10, 2021, April 27, 2021, and

November 12, 2021. CMS also released question and answer documents to help enable

visitation and frequently asked question documents on visitation, such as this example

published March 10, 2022:

https://www.cms.gov/files/document/nursing-home-visitation-faq-1223.pdf accessed June

8, 2022.

Page 14 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

weight. Officials from another nursing home said that residents were at a

higher risk for falls for various reasons including, for example, they were

alone in their rooms and would try to move independently without staff

assistance or with inadequate staff assistance. According to CMS, some

nursing homes may have been overly restrictive on visitation in a manner

that was inconsistent with CMS guidance. CMS noted that the agency

requires nursing homes to implement care plans for each resident to

attain or maintain the resident’s highest practicable physical, mental, and

psychosocial well-being.

In November 2021, CMS updated its guidance to allow visitation and

group activities with no restrictions, noting that the agency recognized

that physical separation from family had taken a physical and emotional

toll on residents.

34

Officials from some of the nursing homes we

interviewed described seeing a visible improvement in residents once

visitation and group activities were allowed again. For example, officials

from one selected nursing home said that depression decreased and

residents began eating better.

There may be other factors that have contributed to worsening resident

mental and physical health during the pandemic. For example, in April

2022, CMS cited significant concerns with the quality of resident care

identified by surveyors, such as weight loss, depression, and pressure

ulcers as a key rationale for its plans to end certain emergency blanket

waivers issued during the pandemic, such as waived training

requirements for certified nurse aides.

35

In addition, according to one

study we reviewed, changes in nursing home resident well-being could be

the result of a variety of causes, including the direct effects of being sick

with COVID-19, fears associated with contracting the virus, grief from

losing friends and loved ones, changes in care practices, such as the

34

See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, QSO-20-39-NH (November 12, 2021

revision).

35

CMS noted that by waiving these training requirements, certified nurse aides may not

have received the necessary training to, for example, help identify and prevent weight loss

in residents. As a result, CMS stated that the agency is concerned about how residents’

health and safety has been impacted by the regulations that have been waived. See

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Update to COVID-19 Emergency Declaration

Blanket Waivers for Specific Providers, QSO-22-15-NH (Baltimore, Md.: April 7, 2022).

Page 15 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

declines in the provision of therapy, and other policies put in place to limit

the spread of the virus.

36

The percentage of nursing homes cited for infection prevention and

control deficiencies during the COVID-19 pandemic was generally

consistent with the years prior. Nursing homes received IPC deficiencies

during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021 for failing to follow

basic practices, such as proper handwashing, but also for failing to follow

COVID-19-specific practices. Officials from the state survey agencies we

interviewed said the most persistent IPC challenges in nursing homes

during the pandemic were often attributed to staffing challenges. Despite

these challenges, stakeholders we interviewed said that nursing homes

had gained valuable knowledge about IPC during the pandemic.

Our analysis of CMS data shows that the percentage of nursing homes

cited for infection prevention and control deficiencies in 2020 and 2021

was generally consistent with the years prior.

37

Specifically, about 44

percent of nursing homes were cited for at least one IPC deficiency in

2020, which decreased to about 37 percent in 2021. Prior to the

pandemic, in 2018 and 2019, about 43 percent of nursing homes were

cited for at least one IPC deficiency. We also previously reported that, in

each year from 2013 through 2017, the percent of all nursing homes

inspected by state surveyors with an IPC deficiency ranged from 39 to 41

percent.

38

According to most of the state survey agency officials we interviewed and

our review of IPC deficiency narratives written by state surveyors, nursing

homes received IPC deficiencies during the pandemic for failing to follow

basic IPC practices, such as proper handwashing and personal protective

equipment usage, but some state survey officials noted that nursing

homes also received IPC deficiencies for failing to follow COVID-19-

specific practices such as failing to quarantine and isolate COVID-19

positive residents. (See app. II for illustrative examples of IPC

deficiencies.) When examining the severity of the deficiencies cited, we

36

See M. Levere, P. Rowan, A. Wysocki, “The Adverse Effects of the COVID-19

Pandemic on Nursing Home Resident Well-Being,” JAMDA, vol. 22, no. 5 (2021): 948-

954.

37

For this analysis, we analyzed the deficiency code F-880 for nursing homes that were

cited for not meeting federal standards for establishing and maintaining an IPC program.

38

See GAO-20-576R.

Infection Prevention

and Control

Deficiencies

Persisted in Nursing

Homes during the

COVID-19 Pandemic

The Percentage of

Nursing Homes Cited for

Infection Prevention and

Control Deficiencies

during the Pandemic Was

Generally Consistent with

Prior Years

Page 16 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

found that in 2018 and 2019, only 1 percent of IPC deficiencies were

classified at a high severity where the surveyor determined that residents

were harmed or in immediate jeopardy of being harmed.

39

However,

during the pandemic in 2020 and 2021, this increased to about 8 and 4

percent, respectively.

CMS put greater emphasis on IPC when it temporarily suspended

standard surveys and introduced focused infection control surveys

beginning in March 2020. (See app. III for more information on the

focused infection control survey and the next finding for how it fits in with

other actions CMS took during the pandemic.) While the enhanced

scrutiny of IPC through CMS’s focused infection control survey does not

appear to have resulted in a greater percentage of nursing homes being

cited by surveyors for IPC deficiencies during the pandemic compared to

prior years, the focused infection control surveys were the key source of

IPC deficiencies in 2020.

40

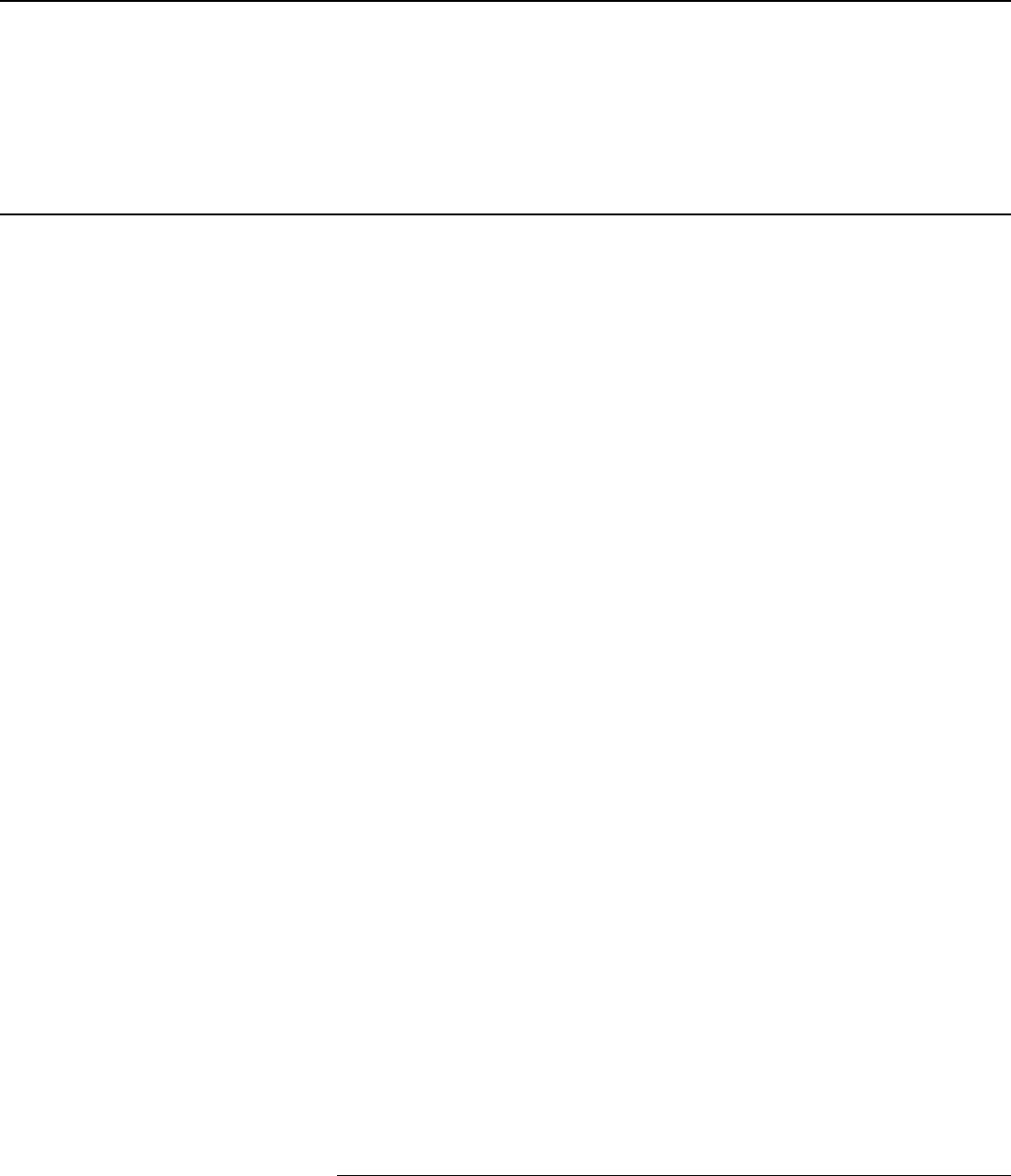

Specifically, our analysis of the CMS data

showed that, prior to the pandemic, the vast majority of IPC deficiencies

were identified during standard surveys (about 84 percent in 2018 and

39

This is consistent with our prior reporting, where we found that, in each year from 2013

through 2017, nearly all IPC deficiencies (about 99 percent in each year) were classified

by surveyors as not severe, meaning the surveyor determined that residents were not

harmed. See GAO-20-576R.

IPC deficiencies were also categorized by scope—whether the incident was an isolated

occurrence, a part of a pattern of behavior, or a widespread behavior. In 2018 and 2019,

about 50 percent of IPC deficiencies cited were categorized as isolated, about 30 percent

categorized as a pattern, and about 14 percent categorized as widespread. In 2020 and

2021, about 35 percent of IPC deficiencies cited were categorized as isolated, about 40

percent were categorized as pattern, and about 20 percent were categorized as

widespread. Percentages do not add to 100 due to rounding.

40

In January 2021 and again in November 2021, CMS gave state survey agencies more

capacity to conduct additional standard surveys by changing the criteria for how often a

focused infection control survey must be conducted, after a year of state survey agencies

mainly conducting the more frequent focused infection control surveys. See Centers for

Medicare & Medicaid Services, COVID-19 Survey Activities, CARES Act Funding,

Enhanced Enforcement for Infection Control Deficiencies, and Quality Improvement

Activities in Nursing Homes, QSO-20-31-ALL (Baltimore, Md.: June 1, 2020) (revised

January 4, 2021) and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Changes to COVID-19

Survey Activities and Increased Oversight in Nursing Homes, QSO-22-02-ALL (Baltimore,

Md.: Nov. 12, 2021). Nursing homes could be inspected multiple times in a calendar year

with a focused infection control survey, depending on the number of outbreaks. On

average, nursing homes had four focused infection control surveys in 2020 and three in

2021. In each year from 2018 through 2021, nursing homes had, on average, two

complaint or facility-reported incident investigations and one standard survey.

Page 17 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

2019).

41

In contrast, in 2020, which encompasses the period when

standard surveys were temporarily suspended, the majority of IPC

deficiencies were identified during focused infection control surveys—60

percent in 2020, which decreased to 31 percent in 2021. Further, as the

percentage of IPC deficiencies identified during standard surveys

dropped during the pandemic, the percentage of IPC deficiencies

identified during complaint or facility-reported incident inspections

increased from about 16 percent in 2018 and 2019, to 26 percent in 2020

and 29 percent in 2021. (See fig. 3.)

Figure 3: Type of Survey or Investigation Used by State Survey Agencies to Identify

Infection Prevention and Control Deficiencies, 2018 through 2021

Notes: For 352 of the 34,522 IPC deficiencies cited from 2018 through 2021 (about 1 percent), we

were unable to determine from CMS’s data whether the deficiency was identified during a standard

survey, complaint or facility-reported incident investigation, or focused infection control survey. We

excluded these deficiencies from our percentages.

41

For 352 of the 34,522 IPC deficiencies cited from 2018 through 2021 (about 1 percent),

we were unable to determine from CMS’s data whether the deficiency was identified

during a standard survey, complaint or facility-reported incident investigation, or focused

infection control survey. We excluded these deficiencies from our percentages.

Page 18 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

CMS’s suspension of standard surveys and shift to prioritizing the new

focused infection control survey in 2020 was a factor contributing to

standard survey backlogs in some states due to the growing number of

nursing homes exceeding the federal standard of 15 months without a

standard survey.

42

According to CMS data, as of April 2022, about 40

percent of nursing homes went at least 16 months without receiving a

standard survey.

43

Our review of CMS data found that about 95 percent of

nursing homes had a standard survey conducted in each of the 2 years

we examined prior to the pandemic. During the pandemic, only 28

percent of nursing homes had a standard survey in 2020 while nearly all

homes had at least one focused infection control survey, resulting in half

as many total deficiencies as prior to the pandemic. In 2021, about 57

percent of nursing homes had a standard survey, and about 80 percent of

nursing homes had at least one focused infection control survey, but the

resulting number of total deficiencies cited by surveyors was still about

one-quarter less than pre-pandemic levels.

44

This may be because the

standard survey provides a comprehensive assessment across multiple

areas of a nursing home’s safety and quality of care, while the focused

infection control survey is more narrowly scoped to assess a nursing

home’s IPC practices in light of COVID-19.

Our analysis of CMS data shows that a smaller percentage of nursing

homes were cited for eight other IPC deficiency codes during the time

42

According to CMS, some state survey agencies had staffing issues during the pandemic

that hindered their ability to conduct standard surveys, including staff reassignments and

retirements, which also contributed to the backlog. For example, CMS officials said that

many states had to pull their surveyors, most of whom were nurses, from their survey

roles and deploy them to provide direct care to community residents or to fill other clinical

roles in response to the pandemic. Also, many state survey agencies saw an increase in

complaint allegations that needed to be investigated, which took resources away from

conducting standard surveys.

43

This is a decrease from May 2021, when the HHS Office of Inspector General reported

that 71 percent of nursing homes had gone at least 16 months without receiving a

standard survey. See HHS Office of Inspector General, States’ Backlogs of Standard

Surveys of Nursing Homes Grew Substantially During the COVID-19 Pandemic, OEI-01-

20-00431 (Washington, D.C.: July 27, 2021). One factor contributing to this decrease

could be the steps CMS announced in November 2021 to assist state survey agencies in

addressing the backlog of standard surveys, such as by revising the criteria for conducting

a focused infection control survey and guidance for resuming standard surveys. See

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, QSO-22-02-ALL (Nov. 12, 2021).

44

The percentage of nursing homes with a complaint or facility-reported incident

investigation was about 53 percent in 2018, about 56 percent in 2019, about 45 percent in

2020, and about 52 percent in 2021.

Page 19 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

period examined.

45

Specifically, four of these eight IPC deficiency codes

were established by CMS during the pandemic.

46

For example, a

deficiency code for not meeting federal standards for informing residents,

representatives, and families of COVID-19 cases in a nursing home went

into effect in May 2020 and, in 2020 and 2021, less than 3 percent of

nursing homes inspected by surveyors were cited for this deficiency code.

The remaining four IPC deficiency codes were established by CMS in the

years prior to the pandemic. For example, the antibiotic stewardship

program deficiency code went into effect in November 2017 and, from

2018 through 2021, 5 percent or less of the nursing homes inspected by

surveyors were cited for this deficiency code. (See app. IV for additional

data on deficiencies cited.)

Officials from seven of the eight state survey agencies we spoke to said

that persistent IPC challenges faced by nursing homes during the

pandemic, were rooted in staffing challenges, including staffing shortages

and high rates of staff turnover.

47

According to CMS officials, the reasons

for staffing shortages can be complex and unclear, ranging from an

inadequate recruitment pool to management decisions. Officials we

interviewed from four state survey agencies said that, if a nursing home

does not have enough staff, it could be challenging for staff to adhere to

proper IPC practices, such as taking the time to properly put on and

remove personal protective equipment or wash their hands between

caring for multiple residents. Officials from one state survey agency we

interviewed said that staffing shortages have occurred in nursing homes

throughout the pandemic because, for example, employees are out sick.

In addition, officials from four nursing homes we interviewed said that

they have sought to adhere to CDC guidance recommending a dedicated

space in the home, if possible, for residents with confirmed COVID-19

45

These eight other deficiency codes are F-881 for the antibiotic stewardship program, F-

882 for the infection preventionist role, F-883 for influenza and pneumococcal

immunization, F-945 for infection control training, F-884 for reporting to the National

Healthcare Safety Network, F-885 for reporting to residents, representatives, and family,

F-886 for COVID-19 testing for residents and staff, and F-887 for COVID-19

immunizations.

46

See 42 C.F.R. § 483.80(d)(3), (g), (h) (2021).

47

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, nursing homes have historically struggled with

staffing shortages and high rates of staff turnover. For more, see National Academies of

Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, The National Imperative to Improve Nursing Home

Quality: Honoring Our Commitment to Nursing Home Residents, Families, and Staff

(Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2022).

Selected State Officials

Attributed Persistent

Infection Prevention and

Control Challenges to

Staffing Shortages and

High Turnover

Page 20 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

infections, which has resulted in additional staffing needs.

48

Officials from

seven of the nine nursing homes we spoke with said they have

experienced a staffing shortage during the pandemic.

Officials from five of the state survey agencies we spoke with noted that

there had been a lot of staff turnover during the pandemic, which made it

difficult for a home to ensure that new or temporary staff are trained on

IPC. (In response to the pandemic, CMS gave nursing homes more

flexibility in hiring temporary employees to work as nurse aides by

suspending certain training and certification requirements.

49

) According to

officials from one state survey agency, some of these temporary

employees had never worked in a nursing home before. Officials from

some nursing homes we interviewed also reported using temporary staff

from nurse staffing agencies. Officials we interviewed from three state

survey agencies said that while nursing homes typically do in-service

training for their own permanent staff, they may not have had the time or

resources to provide the same training to temporary staff during the

pandemic, including staff from nurse staffing agencies. Officials from

seven nursing homes we interviewed noted that this was compounded by

the challenges of keeping staff trained on guidance, which officials said

was constantly changing due to the changing circumstances of the

pandemic.

48

CDC guidance specifies that staff should be assigned to work only in this unit when it is

in use and that at a minimum, staff in the COVID-19 unit should include the primary

nursing assistants and nurses assigned to care for these residents. Accessed on

November 8, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/long-term-care.html.

49

Specifically, from March 2020 through June 2022, CMS waived the requirement that a

nursing home not employ anyone for more than 4 months unless they meet certain

training and certification requirements to address potential staffing shortages in nursing

homes due to the COVID-19 pandemic. See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services,

COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers for Health Care Providers, (Baltimore,

Md.: March 13, 2020) and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, QSO-22-15-NH

(April 7, 2022).

Page 21 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

Nursing home officials we interviewed from our selected states said that

nursing homes gained valuable knowledge about IPC practices during the

COVID-19 pandemic. For example, nursing home officials said their

understanding of the significance and additional application of basic IPC

practices—such as the importance of proper handwashing and the proper

use of personal protective equipment—was enhanced. Officials from one

nursing home said that, prior to the pandemic, the home would conduct

an annual IPC “boot camp” training but the pandemic taught them that

those IPC skills were easy to forget when they were not constantly put

into practice. An official from another nursing home said that the IPC

lessons that staff learned during the COVID-19 pandemic were applicable

to preventing the spread of other types of infections.

Nursing home officials we interviewed also described learning new

COVID-19 specific practices, such as how to conduct on-site testing, set

up quarantine and isolation units, and screen visitors and staff. Officials

from one nursing home described developing a process for swabbing and

testing nearly 150 staff members for COVID-19 twice a week. Officials

from another nursing home said they learned how to work with the design

of their building to locate adequate quarantine and isolation spaces.

Officials from two other nursing homes described IPC practices they

implemented during the pandemic that they hoped to continue going

forward. For example, officials from one nursing home said that when the

pandemic ends they plan to continue the visitor and staff symptom

screening they put in place for COVID-19 to prevent the spread of

infections.

Our review of agency documentation and interviews with agency officials

show that CMS and CDC took numerous actions to improve infection

prevention and control both prior to and during the pandemic. For

example, prior to the pandemic, CMS required nursing homes to

designate an infection preventionist on staff and, during the pandemic,

CMS and CDC provided infection prevention resources to nursing homes.

(See app. V for a full list of IPC actions identified by CMS and CDC.)

Despite Challenges,

Nursing Home Officials

from Selected States

Reported Gaining

Knowledge about Infection

Prevention and Control

Practices during the

Pandemic

CMS and CDC Took

Actions to Strengthen

Infection Prevention

and Control but

Should Do More

CMS and CDC Took

Numerous Actions on

Infection Prevention and

Control

Page 22 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

Examples of actions CMS and CDC took prior to the COVID-19 pandemic

include the following:

• Required designated infection preventionist. CMS updated IPC

requirements to include the requirement that nursing homes designate

at least one infection preventionist to oversee the facility’s IPC

program, effective beginning November 2019.

• Developed infection preventionist training. To support the infection

preventionist requirement, CMS, in consultation with CDC, developed

a free online infection preventionist training program that was

available to nursing homes as of March 2019.

50

The specialized

training provided content covering a range of IPC topics to prepare

infection preventionists for their role.

• Conducted IPC pilot program and released Infection Control

Worksheet tool. To help assess and prevent infections in nursing

homes, CMS, in consultation with CDC, conducted a 3-year IPC pilot

project from fiscal year 2016 through 2018, which used a worksheet

tool, developed with CDC and expert input, to identify gaps in nursing

home IPC practices and guide assistance to address those gaps.

51

CMS released the worksheet as an IPC self-assessment tool to

nursing homes in November 2019.

52

Examples of key actions CMS and CDC took during the pandemic include

the following:

• Initiated focused infection control surveys. In March 2020, CMS

made key changes in how it oversees nursing homes by requiring

state survey agencies to conduct a new survey type known as the

focused infection control survey that assessed IPC-related

requirements specific to COVID-19, such as adherence to visitor

50

See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Specialized Infection Prevention and

Control Training for Nursing Home Staff in the Long-Term Care Setting is Now Available,

QSO-19-10-NH (Baltimore, Md.: March 11, 2019).

51

See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Infection Control Pilot Project, S&C-16-

05-ALL (Baltimore, Md.: Dec. 23, 2015).

52

For the pilot, the new survey tool was used for educational purposes rather than to

assess compliance with existing IPC requirements. After the surveyors assessed the

participating nursing homes’ IPC practices, the nursing homes were provided with

technical assistance based on the survey’s results. See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services, S&C-16-05-ALL (Dec. 23, 2015).

The infection preventionist role

The infection preventionist is a nursing home

employee with training in infection prevention

and control who is responsible for the home’s

program for preventing, identifying, reporting,

investigating, and controlling infections and

communicable diseases. Beginning

November 2019, the Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services (CMS) required all nursing

homes to designate one or more infection

preventionists who has completed specialized

training in infection prevention and control and

who works at the nursing home at least part-

time. Some of the responsibilities of the

infection preventionist may include contact

tracing during an infectious disease outbreak,

reporting surveillance data, and educating

staff on proper adherence to infection

prevention and control practices.

Source: GAO summary of CMS and the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention documents. | GAO-22-105133

Page 23 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

screening and personal protective equipment protocols.

53

(See app.

III.)

• Restricted visitation and group activities. In March 2020, to limit

the transmission of COVID-19, CMS temporarily restricted visitation

from all visitors and non-essential health care personnel, except for

certain compassionate care situations and suspended group

activities.

54

In November 2021, CMS lifted these restrictions.

55

• Developed IPC-specific training and technical assistance. CMS

and CDC developed training and technical assistance resources to

help nursing homes implement IPC practices. For example, in May

2020, CMS released a toolkit of COVID-19 best practices.

56

In June

2020, CMS deployed a network of quality improvement organizations

to provide technical assistance to approximately 3,000 low performing

nursing homes with a history of infection control challenges.

57

Beginning in July 2020, CDC deployed “strike teams” of infection

prevention and public health professionals to nursing homes facing

53

CMS continued to require state survey agencies to conduct high-priority complaint

investigations, such as those conducted in response to alleged abuse or neglect. See

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Prioritization of Survey Activities, QSO-20-20-

ALL (Baltimore, Md.: March 20, 2020).

54

These restrictions included ombudsmen, which are advocates for nursing home

residents. These restrictions were later clarified to allow certain conditions for visitation,

such as to allow residents access to long-term care ombudsmen. See Centers for

Medicare & Medicaid Services, QSO-20-14-NH (Mar. 13, 2020 revision) and Centers for

Medicare & Medicaid Services, Nursing Home Five Star Quality Rating System Updates,

Nursing Home Staff Counts, Frequently Asked Questions, and Access to Ombudsman,

QSO-20-28-NH (Baltimore, Md.: April 24, 2020 and Jul. 9, 2020 revision). After the initial

restrictions, CMS made changes to its visitation guidance multiple times during the

pandemic to allow increased visitation and group activities. See Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services QSO-20-39-NH (Sept. 17, 2020), revised March 10, 2021 and April 27,

2021.

55

See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, QSO-20-39-NH (Nov. 12, 2021

revision).

56

See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, CMS Issues Nursing Homes Best

Practices Toolkit to Combat COVID-19, May 13, 2020, accessed April 18, 2022,

https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-issues-nursing-homes-best-

practices-toolkit-combat-covid-19.

57

See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, QSO-20-31-ALL (June 1, 2020).

Page 24 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

challenges with infection control.

58

In August 2020, CMS released

online IPC training courses developed in consultation with CDC.

• Mandated COVID-19 surveillance reporting. In May 2020, CMS

required nursing homes to report data at least weekly through CDC’s

National Healthcare Safety Network on COVID-19 cases and deaths

among residents and staff, personal protective equipment supplies,

access to testing, and staff shortages, among other things.

59

• Increased IPC enforcement actions. In June 2020, CMS increased

financial and other penalties, such as requiring directed plans of

correction, for nursing home noncompliance with IPC requirements

and made enforcement actions more significant for nursing homes

with a history of past infection control deficiencies.

60

58

The strike teams identified challenges related to staffing, personal protective equipment

supplies, COVID-19 testing, and infection prevention and control measure implementation.

See L. Anderson et al., “Protecting Nursing Home Residents from COVID-19: Federal

Strike Team Findings and Lessons Learned,” New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst

(June 28, 2021).

59

85 Fed. Reg. 27,550, 27,627 (May 8, 2020) (codified at 42 C.F.R. § 483.80(g)). Until

December 31, 2024, the new requirement provides for these data to be reported at the

federal level through CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network and to be updated and

publicly reported. Prior to this reporting requirement, state and local health departments

may have required nursing homes to report certain COVID-19 related information to them

as part of their infectious disease surveillance programs. See 42 C.F.R. § 483.80(a)(2)(ii)

(2021). In May 2021, CMS also required nursing homes to report COVID-19 vaccine and

therapeutics treatment information to the CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network.

Medicare and Medicaid Programs; COVID–19 Vaccine Requirements for Long-Term Care

Facilities and Intermediate Care Facilities for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities

Residents, Clients, and Staff, 86 Fed. Reg. 26,306, 26,336 (May 13, 2021) (codified at 42

C.F.R. § 483.80(g)(1)(viii)-(ix)).

60

As part of these efforts, CMS encouraged state survey agencies to develop and issue to

noncompliant nursing homes directed plans of correction, as their enforcement action, in

which state survey agencies specify actions a nursing home must take to address

infection control deficiencies, such as obtaining further IPC training or hiring an IPC

consultant. See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, QSO-20-31-ALL (June 1,

2020).

On February 28, 2022, the White House announced that it would lead further efforts to

improve quality and safety in nursing homes through enforcement actions. For example, it

announced a commitment to hold poorly performing nursing homes accountable for

improper and unsafe care by expanding financial penalties and other sanctions and

including more nursing homes in an enhanced oversight program targeting the poorest

performers.

Page 25 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

Nursing home and state survey agency officials reported to us what they

believed were advantages and disadvantages for selected IPC actions

taken before and during the pandemic. For example, state survey agency

and nursing home officials told us that CMS’s requirement to designate

an infection preventionist was crucial to nursing homes during the

COVID-19 pandemic. See table 1.

Stakeholders Reported

Advantages and

Disadvantages of CMS

and CDC Infection

Prevention and Control

Actions

Page 26 GAO-22-105133 Nursing Home Infection Control

Table 1: Selected Federal Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) Actions and Examples of Stakeholder-Reported Perspectives

on Advantages and Disadvantages

Action

Description

Advantages

Disadvantages

Required designated

infection preventionist

The Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services (CMS)

updated IPC requirements to

include the designation of

infection preventionists.

•

Critical role in nursing homes

during the pandemic (eight of

nine nursing homes and five of

eight state survey agencies)

•

Requirement needs

strengthening to ensure

sufficient infection preventionist

staffing levels (two of nine

nursing homes and three of

eight state survey agencies)

• Difficult to hire or retain infection

prevention professionals in order

to comply (one of nine nursing

homes and two of eight state

survey agencies)

Developed infection

preventionist training

CMS, in consultation with the

Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention (CDC),

developed infection