Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 2

Abstract

Today’s expanding disaster landscape demands crisis managers to congure their

organizations to handle a wider range of extreme events. This requires more varied

capabilities, capacity and delivery of services. The article proposes that crisis managers

must move away from organization-centered planning to a system-wide approach for

preparedness. We lay out the limitations of using the current tiered response triangle for

planning and argue for implementing a system-wide approach by using a Tiered Response

Pyramid to increase response capabilities and surge capacity for large scale disasters.

The tiered response pyramid oers crisis managers a way to visualize multiple response

options that leverage each other’s resources and create a more resilient response system

for complex events.

Suggested Citation

Pfeifer, Joseph W. and Roman, Ophelia. “Tiered Response Pyramid: A System-Wide Approach

to Build Response Capability and Surge Capacity.” Homeland Security Aairs 12, Article 5

(December 2016). https://www.hsaj.org/articles/13324

Introduction

Natural disasters, terrorism, violent extremists, industrial and transportation accidents,

cyber-attacks, infrastructure failures, and utility disruptions are some of the diverse

challenges crisis managers are called to address. This broadening disaster landscape

requires crisis managers to congure their response organizations to handle a wider range

of extreme events, meaning that they need more varied capabilities, capacity and delivery of

services. However, even as they have diversied their resources, crisis managers have seen

responses outstripped by the overwhelming demand and cumulative eects of extreme

events.

This article oers a system-wide approach to crisis management planning that seeks to

decrease the fragility of current response capabilities during large scale disasters. To assist

crisis managers in overcoming response limitations, we argue that crisis managers must

move away from organization-centered planning to a system-wide approach for building

crisis response capacity, capabilities, and delivery. The article lays out the shortcomings of

using the current tiered response triangle for planning. We argue instead for crisis managers

to enhance their organization-centered tiered triangle by implementing a system-wide

Tiered Response Pyramid to increase response capabilities and surge capacity during large

scale disasters. The next crisis will come as a shock in timing, location and form, but how

crisis managers respond should not be a surprise. To avoid insucient responses and poor

coordination, crisis managers must not only look inward at their own organization, but must

also look outward at the whole system’s capabilities and capacity. The Tiered Response

Pyramid is a tool for crisis managers to visualize a system-wide response to disasters.

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 3

Operational Limits

When large and complex disasters unfold, emergency management organizations face

demands that swiftly surpass their response capacity. This incredible strain has been

observed during natural disasters like Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy or terrorist attacks

like those which occurred on September 11, 2001. These “catastrophic disasters” are

dened by the Department of Homeland Security’s National Response Framework as an

event that “results in extraordinary levels of mass casualties, damage or disruption severely

aecting the population, infrastructure, environment, economy, national morale and/or

government function.”

1

These events are not only noteworthy for the extreme impact, but

also for the novelty and complexity of the response required. In order to respond eectively,

organizations must increase their capacity or surge to manage large-scale events.

2

The ability of an organization to surge successfully requires response capacity to withstand

the initial shock, as well as to handle the cumulative stress of an extended crisis response.

3

Louise Comfort, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, uses engineering “fragility

curves” to illustrate this point.

4

Buildings and bridges are designed using “fragility curves”

to determine the cumulative stress that a structure can withstand before failing.

The World

Trade Center was designed to withstand a plane crashing into the building, but was not

engineered to withstand the stress of fast-spreading res that signicantly weaken structural

steel members to the point of collapse.

5

Failures of crisis responses to large scale disasters are often caused by similar compounding

of dierent types of stress. A congressional bipartisan committee found that resources

are generally adequate for most disasters, however, catastrophic disasters like Hurricane

Katrina overwhelmed emergency management response providers, illustrating breaking

points in local, state and federal government response and highlighting the need for a more

exible and adaptive fragility curve for extreme events.

6

The potential stressors or threats that could cause a crisis response fragility curve to fail will

continue to expand as the scope of potential threats and hazards to which crisis managers

must be prepared to address grows. New threats play an important role in expanding

the extreme events risk landscape. Events such as 9/11, the London 7/7 transit bombings,

Mumbai hotel attacks, Kenya’s Westgate Mall, Paris and Orlando active shooters and Ukraine

cyber-attacks illustrate the potential threats of geopolitical terrorism. Additionally, natural

disasters have increased globally since the 1970s, showing a compound annual growth rate

(CAGR) of 3.1% with several large scale disasters making headlines worldwide.

7

These trends,

along with public expectation that government will be able to respond eectively to more

types of events, will increase the pressure for crisis managers to change their fragility curves

so they are less vulnerable to failure. Similar to the military, a crisis manager’s “ability to adapt

will be critical in a world where surprise and uncertainty are the dening characteristics of

our new security environment.”

8

While buildings and bridges can have their “fragility curves” altered by using new stronger

materials or diering designs (e.g., the new One World Trade Center in NYC), crisis response

fragility curves can also be altered by changing capabilities, capacity and delivery to increase

resiliency or decrease the potential for the crisis response to fail. In fact, the dynamic and

unpredictable threat environment of disasters necessitates that leaders constantly evaluate

the eectiveness of their organizational structure and response capacity.

9

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 4

In examining what are the operational limits or breaking points along a response fragility

curve, two important points of analysis for organizations to consider are highlighted. This

evaluation, according to Yaneer Bar-Yan, must consider the scale and complexity of the

incident. Large scale events will require more capacity, while complex events entail more

capabilities.

10

Extreme events are both large and complex, which requires both specialized

skills and a surge of resources. But how can organizations further develop capability and

capacity to withstand greater amounts of stress? In other words, how can an organization

change their “fragility curve” for various crises?

To begin to answer these questions, crisis managers need to be able to compare potential

demands to operational limitations. The Department of Homeland Security, in the Threat

and Hazard Identication and Risk Assessment Guide, recommends understanding operational

needs and limits by dening desired outcomes, capability targets and resources to manage

a scenario. For example, a scenario could be what is needed to “evacuate 20,000 people over

a 3 square mile area within 3 hours prior to the incident.”

11

In order to understand the various

operational needs, crisis managers are best served by classifying the response on three

levels:

• Capability—What can organizations do?

• Capacity—How many resources are available?

• Delivery—When will these resources arrive?

12

Super-Storm Sandy illustrates why crisis managers need to evaluate response across all

three dimensions. The destructive wind and storm surge caused the loss of electric service

to millions of people on the East Coast.

13

Electrical power companies had the capability to

restore power, but lacked the capacity locally and regionally to manage such a wide spread

outage. Utility resources from the West Coast were brought in to meet the capacity needed

to restore power, which changed the delivery timing. It took time to move these additional

resources into the disaster area. To understand why a response succeeds or fails one must

evaluate all three elements. These operational limits are important to consider for any

response activities, such as search and rescue or hazardous material spills.

In order to avoid potential failure points or response chain disruption, crisis leaders need a

deep understanding of the evolving risk environment to compare their response abilities to

the demands of potential crises. Leaders use intelligence briengs and scenario planning

to increase their understanding of the risks. However, the potential risks won’t be clear cut

because “crises are characterized by the absence of obvious solutions, the scarcity of reliable

information when it is needed, and the lack of time to reect on and debate alternative

courses of action.”

14

Thus, surge capability and capacity must be built with a degree of

exibility in mind that allows for uncertainty in the response requirements. In order to

withstand the demands of extreme events, crisis managers need to strengthen response

systems by leveraging an approach that provides adaptive and cost eective solutions.

Identifying where an organization’s response chain breakdowns might occur is a critical

part of planning and requires crisis managers to determine their response needs. Such

knowledge then can be used to build capacity to withstand additional stress before failing.

Understanding these limitations at the outset provides crisis managers with the opportunity

to redesign capabilities and capacity that can better withstand the cumulative stress of

extreme events.

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 5

Tiered Response Triangle

Tier 1

Specialist

Tier 2

Technician

Tier 3

Opera�ons

Increased

Quicker (Delivery Time)

Slower (Delivery Time)

Basic (Capability)

Specialized (Capability)

Increased Capacity

Figure 1: Tiered Response Triangle Model

To address the expanding response needs, as well as economic realities, rst responder

organizations have leveraged a tiered response approach to identify capability and

capacity needs. This tiered organization-centered approach for terrorism and emergency

preparedness was rst proposed by the New York City Fire Department (FDNY) in their 2004

Strategic Plan.

15

Since then, tiered response has become a guiding principle for Homeland

Security.

16

The Tiered Response Model divides mission responsibilities into layered groupings

with each subsequent layer containing resources trained incrementally to a higher response

capability.

17

Thus, a tiered response model is shaped as a triangle; where many more people

are trained with basic-level skills and provide support for those with specialized skills

allowing the organization to boost overall capacity. The vertical axis represents an increase

in capability, while the horizontal axis indicates greater capacity.

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 6

HazMat

Specialists

Increased

Quicker (Delivery Time)

Slower (Delivery Time)

Basic (Capability)

Specialized (Capability)

HazMat

Tech II Units

HazMat

Tech Ambulances

HazMat

Tech I Units

Decontamina�on

Engines

Chemical Protec�ve Clothing

(CPC) Companies

Fire and EMS

Opera�onal Units

Increased Capacity

Figure 2: FDNY Hazardous Material Tiered Response

Decontamination of a civilian at a hazardous material incident illustrates how a multi-tiered

response works (see gure 2). The entire FDNY has been trained to the operational level

for hazardous material response which provides basic coverage throughout the city. The

operational tier is likely to arrive rst to initiate lifesaving eorts. This is followed by several

technician tiers such as HazMat Tech units for rapid rescue, Decontamination Engines to

clean the victims and HazMat ambulances to provide medical care and transport to those

injured. This response is then reinforced by the highly trained specialist level. The tiered

response allows FDNY to increase capacity and speed by integrating each tier into a single

response matrix. In National Response Framework, the Department of Homeland Security

articulates that when federal resources are needed it also provides a similar “tiered level of

support.”

18

The tiered response model was adopted by many crisis managers because it creates

operational and economic eciencies. It is cost prohibitive to train everyone to the specialist

level. Even if funding were available, many essential roles needed in a hazardous material

response or other responses do not require specialist skills. Instead, a variety of units,

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 7

with incremental prociencies can establish an incident response that is highly eective,

economically ecient and sustainable.

19

This tiered response model applies most often

to a single organization’s response skills and/or resources. It is applied sometimes across

organizations sharing geographic proximity and/or common funding by emergency managers.

However, each organization response is structured mostly around their capabilities.

Modifying the Tiered Response Triangle

There are limitations, however, in the tiered response model when events occur outside the

normal routines, such as those requiring a dierent mix of capabilities, additional capacity

or faster delivery of resources. These inadequacies can come from what was excluded in the

initial planning phase or can evolve over time based on changing conditions. For example,

in the latter case, as the number of res decreased, the re service has taken on more and

more emergency medical roles to meet the evolving medical needs of an aging population.

Regarding the former, initial planning can fail when crisis managers only consider the routine

level of stang for the tiers rather than taking into account peak demand. A few simple

modications or updates to the existing tiered response triangle could address these issues

and increase exibility and eectiveness within an organization.

Rebalancing is the redistribution of resources from one tier to another to meet the changing

needs. For example, New York City Police Department’s (NYPD) Emergency Service Units

(ESU) are specially trained SWAT teams that have a nite capacity to protect the city against

multiple terrorist attacks. To supplement these teams, NYPD created a technician level

tier by moving ocers from patrol into several heavy weapons teams (Strategic Response

Groups). By doing this, NYPD rebalanced their tiered response triangle by subdividing a tier

to increase protection without hiring new ocers.

Two common rebalancing approaches are: 1) altering the relative size of existing tiers by

moving resources between the tiers or 2) adding / subdividing tiers by creating a new tier with

its own unique skills. After 9/11, FDNY rebalanced its Hazardous Material Tiered Response

Model as illustrated in Figure 2 by increasing the number of HazMat Tech II Units (from 7 to

12), HazMat Ambulances (from 10 to 39) and Chemical Protection Clothing Companies (from

10 to 29), as well as adding two additional tiers of HazMat Tech I Units and Decontamination

Engines, each with 25 units.

20

Not only can rebalancing impact capability and capacity, but it can signicantly impact

delivery. Having more people geographically dispersed with particular skills increases the

speed with which resources can reach an incident. It is important to regularly re-access

and rebalance according to the evolving risk landscape. Rebalancing can mean additional

cost for extra training and equipment. However, there are considerable cost savings if

overall stang remains the same. When economically feasible, using the tiered response

model to rebalance is a good way to update and enhance an organization’s overall response

capabilities, capacity and delivery.

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 8

Tier 1

Tier 2

Tier 3 B

Tier 3 A

Increased

Quicker (Delivery Time)

Slower (Delivery Time)

Basic (Capability)

Specialized (Capability)

Increased Capacity

Figure 3: Rebalancing Tiers to Enhance Capability

For larger-scale incidents, organizations often are not able to address the response needs by

just rebalancing their tiered response model. Daily tiered capacity is outpaced by response

needs in a crisis. For these incidents, organizations should examine how their tiered response

model can be expanded to meet these needs. For example, how would an organization

surge to meet the eects of a powerful tornado that trapped many people in the collapsed

buildings? In this case, crisis managers would want to expand their capacity at each tier as

opposed to rebalancing across tiers.

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 9

Tier 1

Tier 2

Tier 3

Increased

Quicker (Delivery Time)

Slower (Delivery Time)

Basic (Capability)

Specialized (Capability)

Increased Capacity

Figure 4: Recalling Personnel to Expand Tiered Response for Surge Capacity

Expanding a tiered response model—without permanently hiring more people—requires

bringing into work those members who are o-duty to supplement the response. This

is accomplished through a recall policy that allows an organization to increase response

capacity by recalling groups of o-duty people within one or more tiers, thus expanding the

tiered response outward. Recalling allows an organization to add to the number of trained

people on-duty during a particular incident, taking advantage of their specialized training

and experience.

One element that often needs to be considered ahead of time in a recall is the availability of

extra equipment. For example, if a response organization plans to recall members skilled in

rescue techniques, they will need to have additional rescue equipment available for these

individuals to perform their roles. This can be accomplished by having fully functional spare

equipment or by repurposing equipment. During the Northeast Blackout on August 14,

2003, FDNY added 25 Rapid Response Vehicles by repurposing hazardous material support

trucks, each with two reghters to respond to calls of people trapped in elevators.

Recall policies can be eective in expanding capacity. However, using total recall policies

to bring in all o-duty personnel has signicant limitations in that it creates a surge that is

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 10

sustainable for only 12 to 24 hours because there is no one to relieve the people on duty. On

the other hand, a partial recall reduces the initial surge capacity, but allows for operations

to continue for an extended period. Generally, to operate 24 hours / 7 days a week, 25%

of a work force is on duty at any one time with 75% o duty. To create a sustainable surge,

an organization can pull in an additional 25% of personnel, which doubles the number of

people on-duty; the remaining 50% of o-duty members are held in abeyance and will be

used to relieve of the on-duty crew (switching every 12 hours).

The ability to recall personnel and maintain uninterrupted services is referred to as a

sustainable recall. Organizations that do not have 24/7 responsibility can often expand

their tiered model with a total recall because natural rest periods exist. Without adequate

rest, operating personnel will quickly become ineective and burn out. Based on particular

incident needs, agency leaders can adjust the resources at the organizational level to have a

tiered response model that is balanced and sized appropriately to address the crisis.

Rebalancing and recalling are useful modications that address some gaps created in

the current tiered response model, especially around evolving crisis response needs and

addressing moderate capacity shortages. However, the crisis response required for many

catastrophic events – from Hurricane Andrew (1992) to Super Storm Sandy (2012) – could

not have been addressed by a single organization rebalancing or recalling; the response

to such events requires multiple organizations or a system-wide approach. In addition,

the organization-centric approach fails to address cost issues associated with overlapping

resource investments and those associated with eectively identifying neglected resource

needs. Thus, considering a system-wide vs. organization-centric approach in the planning

stages could help identify the capabilities, capacity and delivery these organizations will

collectively provide to the response eort.

Tiered Response Pyramid

In preparing for these extreme events, it is important to view the overall response, not as

many individual organizations each with their own tiered response model, but rather as

one Tiered Response System created through inter-agency collaboration and coordination.

Emergency management organizations that coordinate municipal or regional response have

emphasized this concept of multiple agency response. However, this shift in optimizing from

a single organization’s response to a multi-organizational response can be confusing when

the same triangle diagram is used for planning within a single organization and multiple

organizations. The tiered response triangle does not create a way to plan for resources

at the system level across organizations with varying capabilities or delivery. To support

the system-wide approach, the two-dimensional Tiered Response Triangle is reshaped

into a three-dimensional Tiered Response Pyramid, which can incorporate other groups.

Establishing a system-wide approach allows crisis managers to capture important depth at

the tier level. The reshaping of the triangle into a pyramid helps a crisis manager to consider

the holistic response, leveraging local, regional, non- governmental organizations (NGO),

the private sector, volunteers, as well as other national and international assets to increase

surge capacity, capabilities and delivery.

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 11

Tier 1

Tier 2

Tier 3

Increased

Capability

Quicker Delivery

Slower Delivery

Basic

Specialized

Recall

On Duty

Next Ops Period

Figure 5: Tiered Response Pyramid Illustrates Increased Capability & Surge Capacity

Moving towards a Tiered Response Pyramid allows organizations to consider not only their

own core competencies, but also other agencies’ crisis mitigation capabilities and capacity.

Using the tiered response pyramid, Incident Commanders and Emergency Operation

Centers can better visualize the system-wide response capabilities and anticipate response

time as additional capabilities requested are often more specialized and drawn from farther

away. When done as part of pre-incident analysis, it drives crisis managers to think more

systematically about response needs and resources at the system level across capabilities,

capacity, and delivery.

This system-wide approach is not entirely new; it has been used in emergency management

planning. However, the scope has remained limited. For example, acknowledging that future

large-scale incidents similar to Super Storm Sandy require more surge capacity than is locally

available, New York City’s FDNY and Oce of Emergency Management (OEM) engaged with

the National Guard in a tiered system-wide solution. NYC developed a memorandum of

understanding (MOU) for the New York State National Guard to respond during disasters.

The MOU denes three key elements: 1) the requesting process, 2) a list of National Guard

capabilities, the amount of resources needed, and how long it will take to deliver the assets,

and 3) how to integrate the National Guard into the incident management systems.

21

The

National Guard is now depicted as part of the surge capacity in New York City’s Tiered

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 12

Response Pyramid. This system-wide approach with the National Guard can also be used

by law enforcement to increase security across a geographical area. The Tiered Response

Pyramid is not just about organizations making agreements with each other, but it is rather

about shifting the mindset of planning to system-wide approach.

The national urban search and rescue program is an example of this coordination and

management mindset at the system-wide level. Several re departments nationally have

heavy rescue and medical rescue capabilities that perform local search and rescue activities,

as well as national activities when demand exceeds local capacity. These smaller response

groups are combined to form regional Urban Search and Rescue (USAR) teams, which are

part of the national USAR program under FEMA.

22

If a disaster requires more than a local and

state response, FEMA will provide a national response, which occurred on 9/11 when eight

USAR teams were sent to World Trade Center and four deployed at the Pentagon.

23

Surge

capacity is further increased by engaging international USAR teams, which was demonstrated

with the international response to Haiti after the earthquakes. This system-wide response

has been eectively used for years by USAR teams; however, it remains largely limited to

specialized teams, rather than being expanded to many other rst responder activities.

The Tiered Response Pyramid not only allows communities to increase capacity, but it also

makes available specialized capabilities that local communities would generally not have

as part of their response, such as radiological experts in case of a radiological or nuclear

incident. Similar scientic experts in bio-terrorism or pandemics are also useful to include

in a system-wide approach. Organizations at the local, state, tribal and federal government

can use the tiered response pyramid to address identied gaps. The system-wide approach

not only allows communities to leverage resources; it also allows people who work in these

specialized groups to gain experience and knowledge that they would not have if they only

served a local community.

A tiered response system recognizes at the outset the reality that no one agency or

jurisdiction has enough resources for extreme events. By shifting to a three-dimensional

tiered response pyramid, crisis managers create greater surge capacity, while making

resource sharing more commonplace. A system-wide approach lls capability and capacity

needs within individual organizations by closely linking the system together. The Emergency

Management Assistance Compact (EMAC) is a national mutual aid agreement that enables

states to share resources, which could be used to create a tiered response system solution.

24

This is assisted by national resource typing, which provides an understanding of equipment

and competencies. These programs provide an easier way for organizations to start shifting

from a tiered response triangle to a tiered response pyramid.

Moving to a tiered response pyramid multiplies the number of response options as many

more resources combinations can be tapped allowing communities to reshape their

capacity, capabilities and delivery. Crisis managers who use the tiered response pyramid

as an analytical tool will be better able to visualize their preparedness strategies and build

more resilient responses. State and regional homeland security agencies along with regional

FEMA oces can help map local communities’ response capabilities, as well as regional and

national capacity. The tiered response pyramid allows organizations to rebalance capabilities

for greater day-to-day operational eciency, while reshaping the organization’s overall

capacity, capabilities and delivery to handle large-scale incidents.

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 13

Implementing Tiered Response Pyramid

When transitioning to a tiered response pyramid, it is important to consider what capabilities

are necessary, how much is required (capacity), and when these resources are needed

(delivery) to determine who might be best suited to own and share a particular capability. In

2013, the American Heart Association reported 359,400 out of hospital cardiac arrests. Even

with all the advances in emergency medical services (EMS), the survival rate was a mere

9.5%.

25

Some crisis managers have started to look at problem not just from an organizational

framework, but from a system-wide perceptive. Cities such as Seattle have dramatically

increased the survival rate from heart attacks to 62% using a system-wide approach.

26

They focused on training citizens in cardio pulmonary resuscitation (CPR), giving 911-phone

instruction on CPR to callers, and providing automatic external debrillators (AED) in many

locations, so someone going into cardiac arrest can receive care quickly by educated citizens

until the paramedics arrive. The paramedics then provide more specialized medical care,

as well as transport to the hospital where the person receives denitive medical care. Each

part of this response sequence or response chain is an integral part of an eective response

and highlights how a system-wide response can expand capabilities, capacity and delivery.

Varying risk probabilities across communities and geographic areas can suggest where it

makes sense to fund these resources. For example, The Department of Homeland Security

has funded response capabilities to address terrorism risks New York City faces, but

those funds end up enhancing the surge capacity more broadly. During recent oods and

snowstorms in upstate New York, FDNY sent rescue and incident management teams as a

regional asset. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, a 300 person reghting team from

FDNY was sent to New Orleans to assist the New Orleans’ Fire Department.

Implementing a tiered response pyramid requires more initial collaboration and coordination

than the tiered response triangle. However, the results for these eorts are an expanded

ability to respond to potential crises. To transition to the tiered response system, crisis

managers need to 1) perform a needs assessment, 2) conduct a tiered response analysis,

and 3) apply the three “R’s” of the tiered response pyramid— rebalance, recall, and reshape.

A crisis response needs assessment requires crisis managers to start by determining potential

threats their communities could experience. Scenario planning can be helpful in converting

threats to response requirements. Scenarios allow one to imagine what could be impacted.

Peter Schwartz describes using scenarios as a tool to help decision-makers deal with

uncertainty by considering alternative courses of action.

27

In developing this initial list of threats, it is important to consider common or routine

threats, as well as threats posed by extreme events. Howitt and Leonard describe extreme

events or novel events as unfamiliar events occurring at an unprecedented scale that

outstrips available resources, making routine responses inadequate and at times even

counterproductive.

28

Due to the wide range of novel events, crisis managers will want to

make sure to invest adequate time in brainstorming around what could happen, yet not to

be so hubristic to think they can predict all scenarios. Crisis managers also might nd using

existing tools and methodologies, such as those laid out in Homeland Security’s Threat and

Hazard Identication and Risk Assessment Guide (THIRA), helpful in creating a full list of threats

and prioritizing those threats that are more likely to happen. One of those threats that rise

to the top of the list is an active shooter incident.

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 14

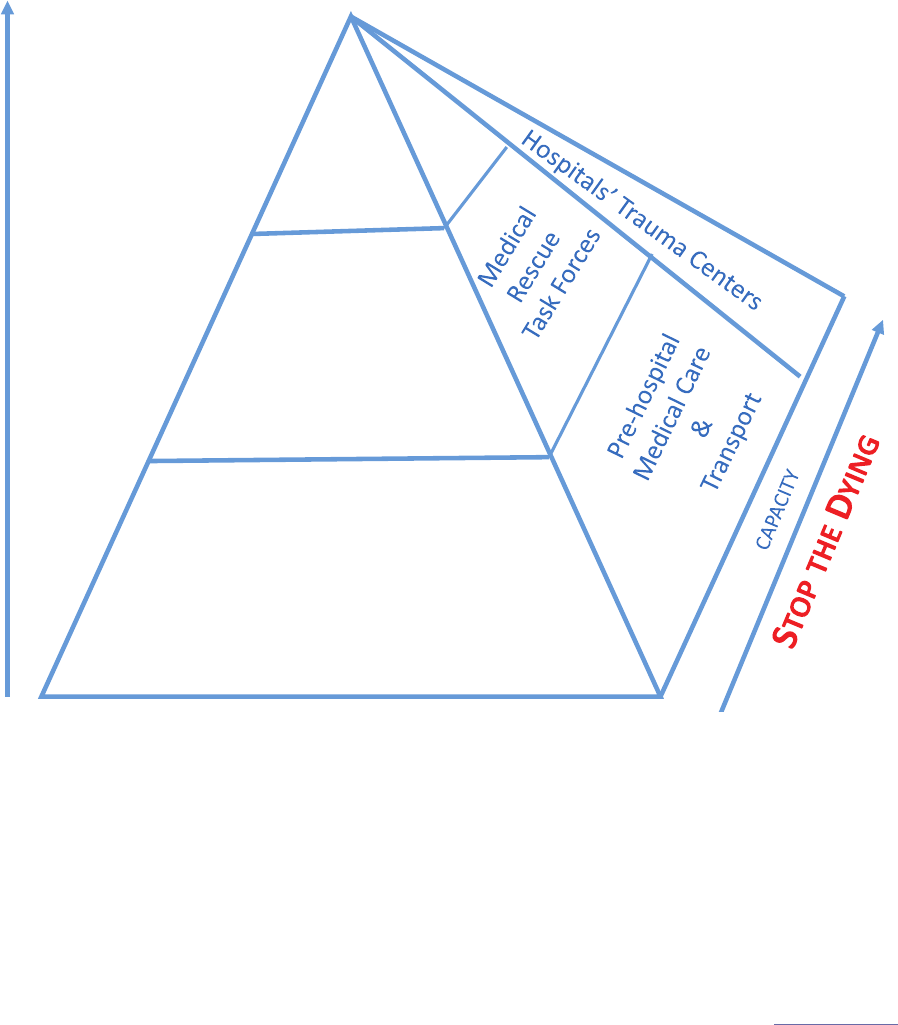

Once threats have been identied, crisis managers need to do an analysis of tiered response

capabilities, capacity, and delivery for addressing each potential incident. Crisis managers

should create a grid that lists all the capabilities needs mapped against the capacity numbers

and delivery times. For example, an active shooter incident requires a dual mission approach

of law enforcement engaging the shooter to stop the killing and emergency medical personnel

quickly providing care for the injured to stop the dying (see Figure 6). From this analysis,

a list of identied capabilities needs is created by mapping the crisis response skills (e.g.,

SWAT teams to engage the shooters, force protection for medical personnel, medical rescue

task force to control bleeding and extract victims, trauma doctors and nurses to operate)

and equipment requirements (e.g., long guns, ballistic protection, tourniquets, hemostatic

clotting agents, trauma center supplies) for this threat. Then these capabilities are tagged

with the capacity and timing requirements.

Hot Zone

SWAT

Warm Zone

Designated by

Law Enforcement

With

Medical Force Protec�on

Cold Zone

Law Enforcement Site Security

&

Resource Staging

S

TOP THE

K

ILLING

C

APABILITY

Figure 6: Tiered Response Pyramid Illustrates a Dual Mission Response to Active Shooter

Incidents

Within crisis management, capacity can be tricky since actual demand for capabilities varies

signicantly. To account for the daily and surge demands, we recommend each capability

be assigned with at least three levels of capacity – routine capacity, sustainable capacity and

maximum capacity. These numbers represent the total people or resources required for

various crisis responses. It is important to also note when resources can arrive because the

timing is just as important as capability and capacity. For example, quickly giving medical

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 15

treatment to stop the bleeding of someone who is injured in a terrorist attack provides for the

greatest chance of survival. This was seen at the Boston Marathon Bombing when seriously

injured patients received lifesaving care at the scene and then were rapidly transported to

hospitals for surgery.

29

Based on the identied gaps, crisis managers can build robust tiered response system-wide

requirements, which can then become a tiered response pyramid by applying the three

“R’s” of the tiered response pyramid. To ll in the tiered response pyramid, the crisis manager

should consider multiple potential solutions, as well as multiple partners to close the gaps.

Crisis managers have signicantly more options available for them with the pyramid than

with the triangle. They can consider internal modications (rebalancing and recall), as well as

external partnerships (reshaping). As potential partnerships are identied, it is important to

consider which control, funding, and deployment models make the most sense for various

capabilities.

The tiered response pyramid reframes crisis response activities from the organizational

level to the system level. It oers a way to visualize crisis management that is no longer

insular, but engages other crisis managers in building partnerships. The interconnectedness

required to develop a tiered response pyramid is the underlying basis for disaster planning

and response.

Making It Work

This system-wide tiered response proved its value on October 23, 2014, when Craig Spenser,

a doctor who treated patients in Western Africa with the group Doctors without Borders,

became ill with Ebola and had to be rushed to Bellevue Hospital in New York City by

ambulance. Multiple organizations mobilized by deploying a version of the tiered response

pyramid for patient care and disease mitigation. FDNY dispatched a HazMat Chief, HazMat

Ambulances and HazMat Tech Units to the doctor’s residence and used personal protective

equipment originally bought for chemical terrorism as bio protections to transport the

patient by ambulance to the hospital. The patient was then handed o to the hospital sta

in bio protective gear and within a short period of time was receiving treatment that saved

his life. The system-wide tiered response contained this potentially deadly epidemic and

proper decontamination procedures ensured the safety of all emergency responders. The

structure of the pyramid allowed seamless adaptation between rst responders and hospital.

This Ebola case demonstrated the exibility of the tiered response system to leverage core

competencies and adapt to novelty.

Making the tiered response pyramid work requires crisis managers to think about the

entire response system’s capability, capacity and delivery. Peter Senge denes this as

“system thinking,” which allows one to see the underlying structures of complexity and

the interrelationships of the system parts.

30

Crisis managers can apply system thinking to

preparedness and response by looking at the whole response pyramid. Without system

thinking, the Ebola response would have been fragmented and unable to adapt, increasing

the potential of spreading this dangerous disease.

When confronted with extreme events, success depends on not just having a list of

capabilities, but a exible response system, which crisis managers can adapt for new crises.

It is about being able to recognize and respond to changing patterns by altering the system’s

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 16

behavior.

31

Response agility is composed of balanced resources in each tier and the ability

to adapt to scale, complexity and novelty. Former four star General, Stanley McChrystal

argues that robustness is achieved by strengthening parts of the system, while resilience

is the results of linking elements that allow resources to recongure or adapt to a changing

environment.

32

The tiered response pyramid is a tool that allows crisis managers to build

robust and resilient response systems by strengthening the tiers and reconguring the shape

of their response fragility curve to a system-wide network for managing major disasters.

When US Airways, Flight 1549 (Miracle in the Hudson) did an emergency landing in the icy cold

waters of the Hudson River, all 155 passengers and crew were rescued because of an agile

tiered response system that emerged as part of collective innovation. Together, New York

Waterways’ Ferries, FDNY Fireboats, U.S. Coast Guard small boats and NYPD Helicopters

remained exible and aligned their agencies’ core skills to improvise on their water rescue

operations for an incident they had not had specically trained for or discussed collectively.

The system-wide tiered response formalizes practices that have started to evolve both at

the local and national levels. By providing a standardized structure, the pyramid oers crisis

managers a common lexicon and an approach to visualize multiple response options that

leverage each other’s resources and create a more resilient response system. The system-

wide tiered response pyramid allows leaders to customize their organizational tiers and

innovate collectively in order to be better prepared for novel and complex events. The

tiered response pyramid gives crisis managers the ability to rebalance and expand, as well

as reshape their response to adapt to an ever changing world of emergencies and disasters

by changing the shape of their response fragility curve.

About the Authors

Joseph Pfeifer is an assistant chief for the New York City Fire Department and founding

director of FDNY’s Center for Terrorism and Disaster Preparedness. He is also a visiting

instructor for the Center of Homeland Defense and Security at NPS, a senior fellow at the

Program for Crisis Leadership at the Harvard Kennedy School, and a senior fellow at the

Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. He holds masters degrees from the Harvard

Kennedy School, Naval Postgraduate School and Immaculate Conception. He is published in

various books and journals and can be contacted at: joe_pfeifer@hks.harvard.edu.

Ophelia Roman recently was a manager in Deloitte’s Crisis Management Practice. She served

on Mayor Bloomberg’s Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency after Superstorm

Sandy, and has also worked multiple times with New York Fire Department starting in 2009.

She holds master degrees from Harvard Kennedy School and Harvard Business School.

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 17

Notes

1 Department of Homeland Security, National Response Framework (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing

Oce, 2013), 1.

2 Department of Homeland Security, National Preparedness Goals (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing

Oce, 2011), 11.

3 Louise K. Comfort, “Rethinking Security: Organizational Fragility in Extreme Events,” Public Administration

Review 62 (September 2002): 102.

4 Ibid.

5 National Institute of Standards and Technology, Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World

Trade Center Disaster: The Emergency Response Operation (Washington, D.C., 2005).

6 Congressional Bipartisan Committee, A Failure of Initiative: Final Report of the Selective Bipartisan Committee

to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Printing Oce,

2006), 14-15.

7 Swiss Re, Sigma World Insurance Database: (http://www.sigma-explorer.com/ Accessed 7/10/15).

8 Donald Rumsfeld, “21st Century Transformation of U.S. Armed Forces,” Speech, National Defense

University, Fort McNair, Washington, DC, January 31, 2002, (http://www.defenselink.mil/speeches/2002/

s20020131-secdef.html).

9 Reid Sawyer & Joseph Pfeifer, “Strategic Planning for First Responders: Lessons Learned from the NY

Fire Department”, In R. Howard, J. Forest, and J. Moore (Eds.), Homeland Security and Terrorism, (New York:

McGraw-Hill Company, 2006), 246-258.

10 Yaneer Bar-Yan, Making Things Work: Solving Complex Problems in a Complex World, (NECSI: Knowledge

Press, 2004), 69.

11 Department of Homeland Security, Threat and Hazard Identication and Risk Assessment Guide

(Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Oce, 2013), 13.

12 Joseph Pfeifer, “Crisis Leadership: The Art of Adapting to Extreme Events,” Harvard Kennedy School’s

Program on Crisis Leadership Discussion Paper Series, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Kennedy School: 2013), 5.

13 New York City, Hurricane Sandy After Action (New York City, 2013).

14 Robert Bertrand and Chris Lajtha, “A New Approach to Crisis Management,” Journal of Contingencies and

Risk Management 10, no. 4 (December 2002): 184.

15 FDNY, Strategic Plan (New York City Fire Department. 2004), 3.

16 Department of Homeland Security, National Response Framework (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing

Oce, 2013), 5.

17 FDNY, Terrorism Preparedness Strategy (New York City Fire Department, 2007), 14.

18 Department of Homeland Security, National Response Framework (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing

Oce, 2013), 7.

19 FDNY, Terrorism Preparedness Strategy (New York City Fire Department, 2007), 14.

20 FDNY, HazMat Tiered Response to WMD Incidents, (New York City Fire Department, 2015).

21 MOU between FDNY, Oce of Emergency Management, and the National Guard, Engaging the National

Guard During a Disaster (2013).

22 FEMA, USAR. (https://www.fema.gov/about-urban-search-rescue#. Accessed 2/16/15).

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 18

23 FEMA, FEMA Mobilizes Twelve Urban Search and Rescue Teams, (https://www.fema.gov/news-

release/2001/09/11/fema-mobilizes-twelve-urban-search-and-rescue-teams. Accessed 7/26/15).

24 FEMA, Emergency Management Assistance Compact (http://www.emacweb.org/, Accessed 2/16/15).

25 American Heart Association, Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics - 2013 Update (http://www.heart.org/

HEARTORG/General/Cardiac-Arrest-Statistics_UCM_448311_Article.jsp, Accessed 7/10/15).

26 King County Public Health, King County Has the World’s Highest Survival Rate for Cardiac Arrest (http://www.

kingcounty.gov/depts/health/news/2014/May/19-cardiac-survival.aspx, accessed 7/26/15).

27 Peter Schwartz, The Art of the Long View, (New York: Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc., 1991), 4.

28 Arnold M Howitt & Herman B. Leonard, with David Giles (Eds.), Managing Crisis: Response to Large-Scale

Emergencies, (Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2009), 275.

29 Herman Leonard, Christine Cole, Arnold Howitt, & Philip Haymann, Why Boston Was Strong: Lessons

Learned from the Boston Marathon Bombings, (Cambridge: President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2014),

28-29.

30 Peter M. Senge, The Fifth Discipline, (New York: Doubleday Publishing, 2006). 68-69.

31 Steven Johnson, Emergence: The Collective of Ants, Brains, Cities and Software, (New York: Scriber Publishing.

2001), 103-104.

32 Stanley McChrystal with Tantum Collins, David Silverman, and Chris Fussel, Teams of Teams: New Rules of

Engagement for a Complex Worlds, (New York: Portfolio/Penguin, 2015), 80.

Homeland Security Aairs, Volume 12 Article 5 (December 2016) WWW.HSAJ.ORG

Pfeifer & Roman, Tiered Response Pyramid 19

Copyright

Copyright © 2016 by the author(s). Homeland Security Aairs is an

academic journal available free of charge to individuals and institutions.

Because the purpose of this publication is the widest possible

dissemination of knowledge, copies of this journal and the articles

contained herein may be printed or downloaded and redistributed

for personal, research or educational purposes free of charge and

without permission. Any commercial use of Homeland Security Aairs

or the articles published herein is expressly prohibited without the

written consent of the copyright holder. The copyright of all articles

published in Homeland Security Aairs rests with the author(s) of the

article. Homeland Security Aairs is the online journal of the Naval

Postgraduate School Center for Homeland Defense and Security

(CHDS). Cover photo by MusikAnimal