© 2016 International Monetary Fund

IMF Country Report No. 16/189

GERMANY

FINANCIAL SECTOR ASSESSMENT PROGRAM

FINANCIAL SYSTEM STABILITY ASSESSMENT

This report on Financial System Stability Assessment on Germany was prepared by a staff

team of the International Monetary Fund. It is based on the information available at the

time it was completed in June 2016.

Copies of this report are available to the public from

International Monetary Fund Publication Services

PO Box 92780 Washington, D.C. 20090

Telephone: (202) 623-7430 Fax: (202) 623-7201

E-mail: publications@imf.org Web: http://www.imf.org

Price: $18.00 per printed copy

International Monetary Fund

Washington, D.C.

June 2016

GERMANY

FINANCIAL SYSTEM STABILITY ASSESSMENT

Approved By

James Morsink

Mahmood Pradhan

Prepared By

Monetary and Capital

Markets Department

This report is based on the work of the Financial Sector

Assessment Program (FSAP) mission that visited Germany in

November 2015 and February–March 2016. The findings were

discussed with the authorities during the Article IV consultation

mission in May 2016. More information on the FSAP may be

found at http://imf.org/external/np/fsap/fssa.aspx

The team comprised Michaela Erbenová (mission chief), Jodi Scarlata (deputy mission chief),

Ulric Erickson von Allmen, Elias Kazarian, Emanuel Kopp, Cecilia Marian, Fabiana Melo, Jean-

Marc Natal, Nobuyasu Sugimoto, Hans Weenink, Christopher Wilson, and TengTeng Xu (all

IMF staff), as well as Jonathan Fiechter, David Scott, Robert Sheehy, Richard Stobo, Ian

Tower, José Tuya, and Marguerite Zauberman (external experts). David Jutrsa provided

research assistance from Washington. The mission met the Ministry of Finance (MOF), the

Deutsche Bundesbank, Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin), the

European Central Bank (ECB), the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), the

Federal Agency for Financial Market Stabilization (FMSA), the European Systemic Risk Board

(ESRB), the Single Resolution Board (SRB), representatives of deposit guarantee schemes,

institutional protection schemes (IPS), industry associations, financial sector firms,

academics, and representatives of the auditing, accounting and legal professions.

FSAPs assess the stability of the financial system as a whole and not that of individual

institutions. They are intended to help countries identify key sources of systemic risk in the

financial sector and implement policies to enhance its resilience to shocks and contagion.

Certain categories of risk affecting financial institutions, such as operational or legal risk, or

risk related to fraud, are not covered in FSAPs.

This FSAP evaluates the risks and

vulnerabilities of the German financial system and reviews both the German regulatory

and supervisory framework and implementation of the common European framework

insofar as it is relevant for Germany.

Germany is deemed by the Fund to have a systemically important financial sector and

the stability assessment under this FSAP is part of bilateral surveillance under Article IV

of the Fund’s Articles of Agreement.

This report was prepared by Michaela Erbenová and Jodi Scarlata, with contributions from

the FSAP team members. It draws on several Technical Notes and Detailed Assessment

Reports on compliance with the Basel Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision

(BCP) and with Principles for Financial Market Infrastructure (PFMI).

June 10, 2016

GERMANY

2 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ___________________________________________________________________________ 6

MACROFINANCIAL SETTING ____________________________________________________________________ 9

RISKS, RESILIENCE, AND SPILLOVERS _________________________________________________________ 15

A. Key Risks Facing the German Financial System ________________________________________________ 15

B. Financial System Resilience ____________________________________________________________________ 19

C. Systemic Risk and Spillovers ___________________________________________________________________ 29

MACRO- AND MICROPRUDENTIAL OVERSIGHT ______________________________________________ 32

A. Macroprudential Policy Framework____________________________________________________________ 32

B. Microprudential Oversight _____________________________________________________________________ 33

FINANCIAL SAFETY NETS _______________________________________________________________________ 40

BOXES

1. Trends in Residential Real Estate ______________________________________________________________ 11

2. Cyber Risk and Financial Stability in Germany _________________________________________________ 34

FIGURES

1. Real Estate and Shipping Developments ______________________________________________________ 10

2. Financial System Structure _____________________________________________________________________ 12

3. Banking Sector _________________________________________________________________________________ 13

4. Bank Liability Structure by Segment ___________________________________________________________ 17

5. Systemic Risk Indicators _______________________________________________________________________ 18

6. Macroeconomic Scenarios—Key Variables ____________________________________________________ 19

7. Solvency Stress Test ___________________________________________________________________________ 21

8. Low Interest Rates and Bank Profitability ______________________________________________________ 22

9. Sovereign Exposures, Risk Index, and Valuation Losses under Stress __________________________ 23

10. LCR Estimates_________________________________________________________________________________ 24

11. LCR and NSFR Reported by German Banks in the BCBS QIS _________________________________ 25

12. Insurance Earnings, Solvency, and Risk Analysis ______________________________________________ 26

13. Insurance Stress Testing Results ______________________________________________________________ 27

14. Financial Sector Interconnectedness _________________________________________________________ 30

15. Global Systemic Risk __________________________________________________________________________ 31

TABLES

1. FSAP Key Recommendations ____________________________________________________________________8

2. Selected Economic Indicators, 2013–17 _______________________________________________________ 44

3. Financial Soundness Indicators for the Household Sector, 2006–15 ___________________________ 45

GERMANY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 3

4. Financial Soundness Indicators for the Corporate Sector, 2006–14 ____________________________ 46

5. Financial Soundness Indicators, 2008–14 ______________________________________________________ 47

6. Germany: Risk Assessment Matrix (RAM) ______________________________________________________ 48

ANNEXES

I. Germany: Implementation Status of 2011 FSAP Recommendations ___________________________ 50

II. Structure of the German Banking System ______________________________________________________ 54

III. Landesbanken—Recent Developments _______________________________________________________ 55

IV. Stress Test Matrix (STeM) for the Banking Sector ____________________________________________ 58

V. Stress Test Matrix (STeM) for the Insurance Sector ___________________________________________ 67

VI. Stress Test Matrix (STeM) for Systemic Risk Analysis _________________________________________ 69

VII. Methodology for Systemic Risk and Spillover Analysis _______________________________________ 70

APPENDIX

I. Report on the Observance of Standards and Codes (ROSCs)—Summary Assessments ________ 74

GERMANY

4 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Glossary

AFS Available for Sale

AIFMD Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive

AML/CFT Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism

AQR Asset Quality Review

AUM Assets Under Management

BaFin German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority

BCP Basel Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision

BIS Bank for International Settlements

BO Beneficial Ownership

BRRD Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive

BU Bottom-up (stress test)

CCB Countercyclical Capital Buffer

CCP Central Counterparty

CDS Credit Default Swaps

CET1 Common Equity Tier 1 Capital

CMG Crisis Management Group

CPMI Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures

CPSS Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems

CRDIV Capital Requirements Directive

CRE Commercial Real Estate

CRR Capital Requirements Regulation

CSD Central Securities Depository

CVA Credit Valuation Adjustment

DGSD

EA

EBA

ECB

Deposit Guarantee Scheme Directive

Euro area

European Banking Authority

European Central Bank

DNFBP Designated Non-financial Businesses and Professions

EEA

EIOPA

European Economic Area

European Insurance and Occupational Pension Authority

ELA Emergency Liquidity Assistance

EM Emerging Markets

EMIR European Market Infrastructure Regulation

ESMA European Securities and Markets Authority

ESRB European Systemic Risk Board

FMI Financial Market Infrastructure

FMSA Federal Agency for Financial Market Stabilization

FSB Financial Stability Board

FSC Financial Stability Committee

FX Foreign Exchange

G-SIBs Global Systemically Important Banks (designated by the FSB)

GERMANY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 5

G-SIIs

Global Systemically Important Insurers (designated by the FSB)

IAIS

International Association of Insurance Supervisors

ICAAP

Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process

ILAAP

Internal Liquidity Adequacy Assessment Process

IOSCO

International Organization of Securities Commissions

IPS

Institutional Protection Scheme

IRRBB

Interest rate risk in the banking book

HQLA

High Quality Liquid Assets

HH

Households

KA FSB’s Key Attributes for Effective Resolution Regimes

LCR Liquidity Coverage Ratio

LSIs Less Significant Institutions (in the context of SSM)

LTV Loan-to-value ratio

MiFID Markets in Financial Instruments Directive

MOF

MOU

German Ministry of Finance

Memorandum of Understanding

MREL Minimum Requirement for Own Funds and Eligible Liabilities

NCA National Competent Authority

NFC Non-financial corporations

NII Net Interest Income

NPL Non-performing Loans

NSFR Net Stable Funding Ratio

ORSA Own Risk and Solvency Assessment

OTC Over-the-counter

PFMI CPSS-IOSCO Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures

PSIs Potentially Significant Institutions

QIS Quantitative Impact Study

RRP Recovery and Resolution Plan

RWA Risk-Weighted Assets

SCR Solvency Capital Requirement (for insurers)

SIs Significant Institutions (in the context of SSM)

SME Small and Medium-size Enterprise

SRB Single Resolution Board

SREP Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process

SRF Single Resolution Fund

SRM

SSM

SSMR

Single Resolution Mechanism

Single Supervisory Mechanism

Single Supervisory Mechanism Regulations

TD Top-down (stress test)

TLAC Total loss-absorbing capacity

UCITs EU Directive on Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferrable

Securities

YTM Yield-to-maturity

GERMANY

6 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Germany’s financial sector plays a key role in the global economy. The country is home to two

global systemically important financial institutions, Deutsche Bank AG and Allianz SE, as well as to

one of the largest global central counterparties (CCP), Eurex Clearing AG. The system is also very

heterogeneous, with a range of business models and a large number of smaller banks and insurers.

Its asset management industry is the third largest in the European Union (EU), while its sovereign

bond market is a safe haven and benchmark for fixed income instruments globally. Consequently,

Germany’s contribution to ensuring the success of the new European financial stability architecture

is crucial for fostering its domestic financial stability and the success of the European reform agenda.

The resilience of the German financial sector is bolstered by major financial sector reforms,

driven by EU-wide and global developments, which are now nearing completion. The

regulatory landscape has changed profoundly with strengthened solvency and liquidity regulations

for banks (the EU Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) and Directive IV (CRD IV)), and the

introduction of macroprudential tools. The establishment of the Single Supervisory Mechanism

(SSM) has positively impacted the supervision of the banking system as a whole, while the bank

resolution regime has been significantly strengthened following the implementation of the EU Bank

Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD). Introduction of Solvency II enhanced the regulatory and

supervisory regime for insurance, leading to a more risk-based approach. The framework for

Financial Markets Infrastructure (FMIs) has been strengthened by the European Market Infrastructure

Regulation (EMIR). Germany is making progress towards compliance with the new EU Directives on

Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities (UCITS) and Alternative Investment

Fund Managers (AIFMD). Overall, there is welcome emphasis on quantitative analysis to augment

the traditional qualitative and relationship-based supervision.

The key risks facing the financial system reflect euro area (EA) and global developments as

well as characteristics unique to the domestic financial architecture:

The ongoing transition to the new supervisory and resolution architecture may give rise to

decision-making and implementation frictions. The newly established European recovery and

resolution framework entails a major cultural change. Its complex decision-making process still

needs to be tested. The coordination of the European and domestic authorities to handle a

systemic crisis is being set up. While the SSM supervisory practices are evolving quickly, the

SRB—in charge of resolution measures for significant German banks—is still in a startup mode.

This constitutes a transition risk until the EA level authority is fully operational.

Low profitability, rooted in banks’ and insurers’ business models, is exacerbated by the

low interest rates. The low interest rates are helping to boost credit demand and stimulate

growth. However, prevailing business models make banks and life insurers particularly

vulnerable to the associated adverse side-effects of unconventional monetary policy. Banks

faced with falling net interest margins may be tempted to adopt risky search-for-yield strategies,

and bank equity prices have been dropping markedly. Low profitability of life insurers hampers

GERMANY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 7

their ability to pay guaranteed yields to policyholders. Real estate assets, while currently broadly

in line with fundamentals, could become overvalued.

A global growth shock, sharp downturn in emerging markets (EMs), or renewed tensions in

the EA could lead to a rapid hike in global risk premia and asset price volatility. This may give

rise to domestic financial risks and second round adverse spillovers because of the globally

interconnected financial sector and the importance of German G-SIFIs for shock transmission.

The uncertainties associated with the possibility of British exit from the EU weigh on the outlook.

Although long-standing challenges remain, the financial system as a whole appears resilient

to these risks:

Households’ and corporate balance-sheets are strong. Deleveraging has progressed steadily,

and mortgage-related debt-service is largely insensitive to rapid changes in interest rates.

Risk-based bank solvency measures indicate substantial capital buffers, and non-performing

loans (NPLs) are generally low and declining, although bank profitability is low and leverage is

high in some institutions. While banks have continued to consolidate and reduce costs, mainly

through branch reductions and increased IT services, further progress is needed.

Notwithstanding severe challenges from low interest rates and Solvency II implementation, life

insurers generally retain significant loss absorption capacity. Large insurers enjoy diversification

benefits from multiple business lines and an international presence, while many small insurers

are less affected by the low interest rates owing to their business mix. Some medium-sized

insurers do not have such clear strengths.

Eurex Clearing CCP has a comprehensive risk management framework. Preliminary results of the

EU-wide stress test indicate that the CCP could withstand an extreme but plausible shock

scenario, covering losses with pre-funded resources.

At this juncture, the German authorities, in close collaboration with their European partners,

should keep their focus on finalizing the agenda and, crucially, ensuring that the new

architecture is effective in practice. In this context, the following priorities are highlighted:

Rapidly completing the processes to facilitate the resolvability of German financial firms while

safeguarding taxpayer resources, and building capacity to implement the new resolution regime.

Expanding further the capacity to monitor financial stability risks and cross-sector spillovers, by

collecting comprehensive and granular data and completing the macroprudential toolkit.

Continuing to integrate quantitative analysis into ongoing supervisory monitoring and

promoting sound risk management practices in banks, including on strengthening the oversight

role of supervisory boards, internal control and audit, related party exposures, and operational

risk.

Key FSAP recommendations are summarized in Table 1.

GERMANY

8 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

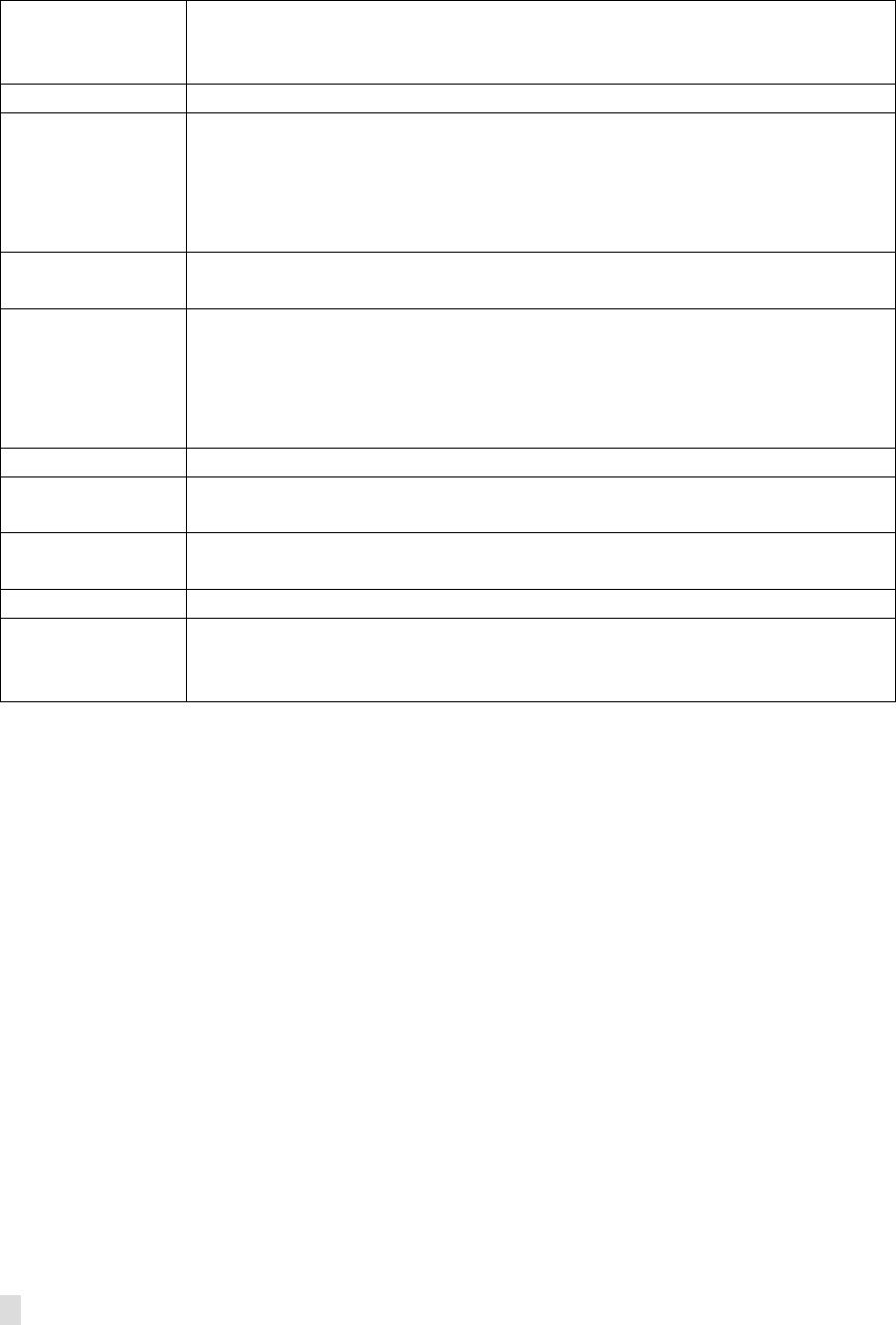

Table 1. Germany: FSAP Key Recommendations

Recommendations Time Frame

1

Financial stability policy framewor

k

Establish a core set of readily-available, consistent data for banks and non-banks to strengthen

financial stability and macroprudential policy analysis

Short term

Develop the legal basis for real estate-related macroprudential tools

Short term

Banking oversight

Implement measures to strengthen the oversight role of the banks’ supervisory board

Short term

Provide guidance on risk management and other supervisory requirements, e.g. regarding loan

portfolio management, concentration and related party risk, and operational risk

Short term

Increase granularity and coverage of bank supervisory data Short term

Strengthen rules and supervisory processes for acquisitions and exposures to related parties Medium term

Streamline and simplify the SSM decision making processes (to be taken at the EU level) Medium term

Insurance oversight

Prepare a communication strategy ahead of the publication of Solvency II indicators

Short term

Extend the application of G-SII toolkit on a risk-based basis to other large groups, including

recovery and resolution planning, enhanced supervision and regular stress tests

Medium term

Communicate supervisory expectations based on the ORSA review more systematically; and use

Solvency II framework to impose capital add-ons

Medium term

Require action plans for companies facing difficulties in meeting Solvency II requirements,

including stress testing to ensure that they would be met even after a plausible shock

Medium term

A

sset management oversight

Intensify frequency of on-site inspections and enhance risk classification methodology

Short term

Introduce stronger rules on reporting of pricing errors and investor compensation rules

Short term

Crisis management and resolution

Develop a formal systemic crisis coordination mechanism including German authorities, SRB and

ECB

Short term

Ensure plans for adequate funding to support the orderly resolution of banks and discretionary

ELA post-resolution

Short term

Remedy operational challenges to resolution actions; ensure authorities retain control during the

resolution process; and test contingency plans in a system-wide crisis exercise

Short term

Review efficiency of SRM decision making (to be taken at the EU level)

Medium term

Financial Market Infrastructure

—

Eurex Clearing

Strengthen the liquidity stress tests and upgrade the secondary site with staffing arrangement

Short term

A

ML/CFT

Increase the effectiveness of the AML/CFT supervisory framework over cross-border banks

Short term

1

Near term is one year. Medium term is 2–3 years.

GERMANY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 9

MACROFINANCIAL SETTING

1. The German economy is growing at a steady pace. Strengthening domestic demand,

bolstered by robust labor market developments, higher public expenditures and lower oil prices

(Table 2) offset a weaker foreign environment in 2015.

2. Private sector balance sheets continue to strengthen as monetary conditions ease and

house prices increase (Figure 1, Tables 3 and 4). Households’ (HH) and non-financial

corporations’ (NFC) debt and interest expenses have declined in relation to income. HH debt service

is largely insensitive to rapid rises in interest rates with most mortgage rates being fixed for a 10–15

year period. Following more than a decade-long correction, house prices have risen rapidly since

2010, though still broadly in line with fundamentals. Recent real estate developments warrant

monitoring as pockets of vulnerability may be emerging (Box 1).

3. The authorities have made progress in addressing the 2011 FSAP recommendations

(Annex I). The financial oversight framework has been strengthened. The restructuring of the

Landesbanken is under way but with only a limited progress to reduce non-commercial influences.

Improvements are evident in the intensity of banking and insurance supervision and the adoption of

analytical tools to support system-wide monitoring. The crisis management framework has been

reformed owing to the EU-wide developments. Government support to banks is being wound down.

4. The financial system is dominated by banks and is generally domestically oriented and

robust to shocks—a relatively unchanged financial structure since the last FSAP (Figures 2 and

3, Table 5). The banking system, with assets equivalent to 245 percent of GDP, is structured around

three pillars and has gone through a sustained period of consolidation (Annexes II and III).

1

Bank

funding, in aggregate, is more reliant on deposits compared to other advanced economies. Banks’

foreign exposures are a fifth of total assets, with only small exposure to vulnerable emerging

markets and Central and Eastern Europe. Approximately half of the claims are against the foreign

non-bank private sector, followed by banks and the public sector. Germany’s insurance sector is

smaller than its peers as a share of GDP, with guaranteed return life products playing a dominant

role. The asset management sector is the third-largest in Europe as measured by assets under

management, and comprises a broad range of management companies and funds. Financial

infrastructures are fewer than in other financial centers, but are interconnected with G-SIBs.

1

The number of banks has declined by about 100 compared with the time of the last FSAP, with consolidation mainly

taking place at local savings and cooperative banks level.

GERMANY

10 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 1. Germany: Real Estate and Shipping Developments

House prices have reached long-term equilibrium value … … as mortgage credit accelerates significantly…

… and the CRE market is heating up. Pockets of vulnerability may need to be monitored

*Top 5 includes: Berlin, Dusseldorf, Frankfurt, Hamburg and Munich

Container freight prices dropped sharply in 2015 …

… and floating storage (tankers) becomes less profitable

-2

0

2

4

6

8

-40

-10

20

50

80

110

Jan-2004

Jan-2005

Jan-2006

Jan-2007

Jan-2008

Jan-2009

Jan-2010

Jan-2011

Jan-2012

Jan-2013

Jan-2014

Jan-2015

Jan-2016

New loans, 5-10 years New loans, over 10 years

Existing loans, over 5 years (RHS)

Housing Loans

(in percent)

Sources: Bulwiengesa, Bundesbank, Destatis, and IMF staff calculations.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

CRE Investment Turnover

(in EUR bn)

Total

Top 5*

Source: CBRE Research Q4 2014, Q4 2015

20

25

30

35

40

45

70

80

90

100

110

120

1985

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

Real house price index (LHS, 1985=100)

Price to income per person ratio (LHS, 1985=100)

Price to rent ratio

Housing Market Valuation Indices

Sources: Bulwiengesa, Bundesbank, Destatis, and IMF staff calculations.

800

1200

1600

2000

2400

2800

Jul-11 Jan-12 Jul-12 Jan-13 Jul-13 Jan-14 Jul-14 Jan-15 Jul-15

WCI Composite Container Freight

(Benchmark Rate per 40ft Box)

20

40

60

80

100

120

Jan-14 Jun-14 Nov-14 Apr-15 Sep-15

Oil Prices

(Brent USD/Barrel)

Brent Crude Oil

ICE Brent Crude 12 Months Futures

ICE Brent Crude 24 Months Futures

0

6

12

18

24

30

0% - 60% 60% - 80% 80% - 100% 100% - 120% over 120%

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Source: Bundesbank special survey among 116 banks in 24 towns and cities.

*The ratio of a loan to the mortgage lending value of the purchased asset, where a haircut on the market

value is generally applied to reflect the sustainable value of the property. LTV measurement in Germany

therefore differs from other internationally used concepts making comparison with LTVs from other

countries difficult.

New Residential Mortgages by Sustainable LTV Ratio*

(number of banks)

GERMANY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 11

Box 1. Trends in Residential Real Estate

For the fourth consecutive year, house price increases in 2015 exceeded the growth in nominal income,

but with important regional differences. While apartment price increases in the largest and most dynamic

German cities (Berlin, Munich, and Hannover) reached double-digits in 2015H2, sustained East-West migration

continues to weigh on residential prices in former East Germany.

The positive trend in real house prices that started in 2010 broadly reflects fundamentals. Following the

post-reunification fiscally-triggered excesses of the early nineties, real estate prices declined, reaching a trough

in 2009–10. Since then, higher income growth, immigration, supply bottlenecks, declining inventories, higher

construction costs, and record-low interest rates contributed to the positive price trend. In real terms, house

prices have reached a level consistent with measures of long-term equilibrium in 2015, as confirmed by price-

to-rent and price-to-income ratios as well as the Bundesbank’s internal valuation models. As households take

advantage of record-low interest rates to lock-in new mortgage debt, mortgage credit growth has also been

trending up, but at a moderate pace with largely unchanged credit standards.

1

However, recent developments warrant closer monitoring. Despite a pickup in construction activity, supply

continues to fall short of demand in selected areas fueling higher prices. The Ministry for the Environment

estimates that around 400,000 new residential units per year are needed to keep up with current demand, or

about 100,000 more units than are currently put on the market each year. Absent a rise in mortgage interest

rates or a sudden burst in house supply—both rather unlikely in the next couple of years—house prices should

continue to rise quickly in the most dynamic regions. The arrival of refugees will put additional pressure on

vacancy rates and boost house prices in the next few years.

Pockets of vulnerability may be emerging. While the financial stability assessment has been hampered by

the lack of granular loan-by-loan data, survey evidence suggests that for a notable part of mortgage loans in

the largest urban areas, loan-to-value ratios may exceed prudent levels.

2

Future mortgage developments

therefore warrant close supervisory monitoring. Authorities should address administrative housing supply

bottlenecks and ready the macroprudential toolkit.

__________________________________

1

The acceleration in 2015 may have been partially driven by the renewals of a large number of loans granted in 2005

in anticipation of the abolishment of the home owners’ subsidy.

2

Surveys in selected urban areas suggest that about a third of mortgages have a loan-to-value ratio (LTV) of more

than 100 percent based on the German sustainable LTV (Beleihungsauslauf) – a conservative measure that applies a

prudential haircut to the value of properties. Also, debt service exceeds 40 percent of income for about

10–15 percent of indebted households (about 8 percent due to mortgage).

GERMANY

12 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 2. Germany: Financial System Structure

Financial sector remains bank-dominated….

…with conservative business model.

*Measured by Total Assets. Does not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Insurance premia grew in line with GDP …. …with pension funds expanding only moderately.

Market capitalization is low amongst peers… ..while asset management is the third largest in the EU.

68%

5%

9%

3%

4%

2%

8%

Financial System Overall Structure

Banks

Pension Funds

Life Insurers

Reinsurers

Other Insurers

Retail Funds

Special Funds

Source: Bundesbank

0

2

4

6

8

10

2011 2015 2011 2015

Banking System Assets and Liabilities

(in EUR tn)

Cash

Lending to MFIs

Lending to non-MFIs

Participating interests

Other assets

Deposits of MFIs

Deposits of non-MFIs

Debt securities

Capital

Other liabilities

Source: Bundesbank

Total Assets Total Liabilities

0

3

6

9

12

15

Germany Belgium France Italy Spain UK US

Insurance Premium Income

(in percent of GDP)

2011 2014

Source: Statistical Yearbook of German Insurance 2015, IMF WEO Oct 2015

0

5

10

15

20

25

Germany Belgium France Italy Spain UK US

Pension Funds Total Assets

(in percent of GDP)

2011 2013

UK13: 100.7

UK11: 94.0

Source:Statistical Yearbook of German Insurance 2015

US13: 83.0

US11: 71.7

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

UK

Spain

Luxembourg

Italy

France

Belgium

Germany

UCITS

Non-UCITS

Source: EFAMA Quarterly Statistical Release Q4 2014, IMF WEO Oct 2015

4,889

837

UCITS and non-UCITS, Assets Under Management

(in percent of GDP)

0 50 100 150 200 250

Germany*

Austria

Ireland

Luxembourg

Spain

Switzerland

Domestic Stock Market Capitalization

(in percent of GDP)

2011

2014

*Germany excludes “Freiverkehr” (unofficial regulated market)

Source: World Federation of Exchanges

GERMANY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 13

Figure 3. Germany: Banking Sector

Banking system is domestically oriented …. …with a sizable share of exposure to the sovereign.

Bank leverage is masked by strong capital ratio…. ..with an RWA density lowest among peers.

*Leverage is defined as Total Regulatory Capital over Total Assets.

Asset quality remains solid… …but bank return on equity has fallen.

*EA Peers includes: Austria, Germany, Italy, France, Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain.

Domestic

Exposures

80%

Advanced

Economies

w/o China

17%

Central and

Eastern

Europe, CIS

1%

Developing

Asia w/China

0%

Other

2%

Geographical Loan Distribution

2014 Q3

Source: IMF Financial Soundness Indicators

0

4

8

12

16

20

Germany

Belgium

France

Ireland

Italy

Japan

Netherlands

Portugal

Spain

US

Source: : IMF, FRBNY estimates, National sources

AE Bank Claims on Domestic Government, 2014

(in percent of assets)

0

20

40

60

80

100

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

RWA to Total Assets

(in percent)

Germany US G-7, average EA Peers, average

Source: IMF Staff Calculations

0

2

4

6

8

10

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Non-performing Loans

(in percent of total loans)

Germany US G-7, average EA Peers, average

Source: IMF Financial Soundness Indicators, IMF Staff calculations

-10

0

10

20

30

40

2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Return on Equity

(in percent)

Germany US G-7, average EA Peers, average

Source: IMF Financial Soundness Indicators, IMF Staff calculations

0

3

6

9

12

15

0

5

10

15

20

25

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Capital Adequacy and Leverage

(in percent)

Germany CAR US CAR

G-7 Avg. CAR EA Peers Avg. CAR

Germany Leverage, RHS US Leverage, RHS

G-7 Leverage Avg., RHS EA Peers Leverage Avg., RHS

Source: IMF Staff Calculations

GERMANY

14 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Germany: Cross-Border Banking Exposures

Sources: BIS Consolidated Banking Statistics, IMF Staff Calculations.

5. Intermediation is concentrated between HHs and financial institutions, while NFCs rely

less on banks and more on intra-segment financing. HHs are closely interlinked with banks (via

loans; deposits, bank bonds and equity holdings) and insurance companies (via claims on insurance

reserves). NFC financing by households mainly constitutes payments to corporate pension funds.

Insurance companies and investment funds are expanding their claims to investment funds via debt

securities, which have almost doubled since 2008.

Germany: Sectoral Interlinkages, June 2015

Source: FSAP team model and estimation based on Bundesbank data, using the Reingold-Tilford network algorithm Note: The

category “banks” includes all monetary financial institutions as defined by the ECB. All financial instruments for which

comprehensive debtor/creditor relationships exist are taken into account (deposits, debt securities, loans, listed shares,

investment fund shares and claims on insurance corporations and pension funds). The arrows show the direction of

interlinkages (from who to whom) and their thickness indicates strength of interlinkages. The size of the node the

interconnectedness within a sector.

Households NFC

PublicSector

Banks

OtherIntermediaries

Insurance

PensionFunds

InvestmentFunds

0

100

200

300

400

500

US

UK

France

Italy

Spain

Netherlands

Switzerland

Austria

Ireland

Sweden

Public Sector Non-bank private sector Banks

German Banks' Combined Foreign Claims:

Top 10 Countries by Exposure

(in USD bn)

Numbers are from Q2 2015 on an ultimate risk basis.

0

40

80

120

160

200

Italy

Netherlands*

France

US

UK

Japan

Switzerland

Sweden

Spain

Austria

Public Sector Non-bank private sector Banks

Consolidated Foreign Claims on Germany:

Top 10 Countries by Origin

(in USD bn)

Num ber s a re fr om Q2 2015 on an ultim ate ri sk b asis.

Note '*' : For the Netherlands, the breakdown by public sector, non-bank private sector and

banks were were estimated by the corresponding share for total foreign claims on Germany,

as the disaggregated data were not published by the BIS.

GERMANY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 15

RISKS, RESILIENCE, AND SPILLOVERS

A. Key Risks Facing the German Financial System

6. The FSAP analyzed three macrofinancial scenarios using a number of quantitative

techniques (Table 6):

A global stress with recessions in advanced economies, triggered by a tightening of global

financial conditions and credit cycle downturns in emerging economies (EMs): German

exporters would be hit, and both investment and consumption would drop as confidence

deteriorates. A sharp correction of asset prices, paired with strong foreign exchange rate

movements, would affect unhedged market positions and hit banks’ trading income.

The return of the EA crisis: Sovereign yields in highly indebted EA countries would increase

sharply. Flight-to-quality effects would diminish and the ‘core’ countries would see their

refinancing conditions deteriorate, albeit to a lesser extent. Investor sentiment would

deteriorate, and the EA would enter a deflationary phase. The uncertainties associated with the

possibility of a British exit from the EU could usher in a heightened macroeconomic uncertainty

and financial market volatility.

Excessive risk-taking associated with the protracted low interest rate environment: Banks

and insurers may be tempted to adopt risky search-for-yield strategies against the backdrop of

squeezed profitability and persistent structural weakness. Banks are key beneficiaries of the

unconventional monetary policy in the EA through improved growth prospects and borrower

credit worthiness, among other. However, prevailing business models of German banks and

insurers may make them particularly vulnerable to the associated adverse side effects.

2

Separately, lower market liquidity fuels asset price volatility. Banks could see a drop in deposit

funding, and institutional investors could channel funds towards higher-yield investments.

7. The overall stability assessment paints a mixed picture. While reported risk-based bank

solvency indicators point to substantial capital buffers across all pillars, the risk-weighted assets

(RWA) density (at 30 percent on average for large banks) is among the lowest in Europe. Capital

ratios may, therefore, understate risks as leverage remains high for some banks. Bank profitability is

low and cost-to-income ratios are high, reflecting banks’ cost-intensive business model. NPLs are

low and falling on aggregate, although asset quality and provisioning in Landesbanken are below

average. Commercial (and large) banks, Landesbanken, and the regional institutions of credit

2

The impact on banks depends on their capacity to reprice loans, deposits and non-deposit liabilities, the relative

importance of net interest income to profitability, and ability to generate noninterest income. Current negative

interest rates may be unique in accelerating margin compression over time as German banks have a large deposit

base and have so far proven unwilling or legally unable to pass on the negative rates to depositors, while mortgage

loans started repricing to lower rates. See IMF (2016), “Global Financial Stability Report,” April 2016, Chapter 1,

Box 1.3 for a discussion on broader effects of low and negative interest rates on banks.

GERMANY

16 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

cooperatives appear more liquid compared to local savings and cooperative banks, in part owing to

an intra-pillar distribution of liquidity.

Germany: Financial Statement Indicators for Different Types of Banks

(End-2014 data or last available year)

8. A legacy of the crisis has been a shift in the availability and form of funding and

subdued credit growth (Figures 4 and 5). Loose monetary conditions are prominent on the

domestic risk map. The crisis exposed weaknesses in bank funding practices, and precipitated

ongoing restructuring. Short-term markets contracted significantly, while longer-term markets

became more domestically focused. Funding flows across the banking pillars continue to be

concentrated among a few key financial institutions, which themselves receive significant amounts

of intra-pillar financing. The ECB liquidity injections are ensuring a high level of liquidity in the

system, but markets will face further challenges as they adapt to new bank liquidity and leverage

regulations. While the new regulatory regime may result in improved sectoral resilience, it may also

result in higher volatility. Measures to facilitate the transfer of excess liquidity within and across the

banking pillars, and elimination of barriers to competition and consolidation among banks,

particularly within the savings banks and credit cooperatives sectors, could help promote efficient

intermediation of excess savings.

3

3

See Technical Note on “Systemic Bank Liquidity and Funding.”

Inter-

connectedness

Tier 1

Capital

Ratio

Total

Capital Ratio

(CAR)

Liquid Assets

to

Total Assets

Liquid assets

to

ST funding ROAE ROAA

Net

Interest

Margin

Cost to

Income

Ratio

NPL

Ratio

Provisioning

Coverage

Ratio /2

Interbank

Ratio /3

Commercial banks 14.5 22.5 27.9 51.3 3.6 0.5 1.0 79.1 3.2 40.5 159.1

Big banks 14.4 17.6 25.0 47.1 3.3 0.2 1.2 81.6 3.9 42.5 185.2

Savings bank sector 15.4 18.2 11.4 13.3 2.1 0.2 2.3 70.8 3.3 47.4 103.3

Landesbanken 12.7 15.6 21.6 40.1 2.5 0.1 0.8 64.2 6.7 31.9 61.2

Savings banks 15.4 18.3 11.2 12.8 2.1 0.2 2.3 70.9 3.2 46.2 104.0

Cooperative banks 14.1 18.7 9.8 11.1 3.7 0.3 2.5 68.9 3.5 39.9 94.0

Regional institutions of credit cooperatives

13.7 16.8 28.5 48.6 10.0 0.4 0.7 48.6 2.3 31.4 75.2

Other cooperative banks 14.1 18.7 9.8 11.0 3.6 0.3 2.5 69.0 3.5 39.9 94.0

Real Estate & Mortgage Banks 15.3 17.1 14.7 19.8 0.9 0.1 1.2 79.9 2.7 36.5 143.5

Average (arithmetic mean) 15.1 19.3 13.0 19.9 3.2 0.3 2.2 71.8 3.5 44.1 102.6

Source: Bankscope, Bundesbanks and IMF staff calculations.

Notes: Unless otherwise noted, numbers are in percent.

/1 Return on average equity (assets).

/2 Loan loss reserves to impaired loans.

/3 Net interbank lending; money lent to money borrowed. Numbers above (below) 100 percent indicate net liquidity provision (consumption).

Solvency and liquidity Profitability /1 Asset quality

GERMANY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 17

Figure 4. Germany: Bank Liability Structure by Segment

(In EUR billion, September 2015)

9. The banking system faces structural headwinds and will need to adapt. Financial

technology innovation is introducing new competitive pressures while the post-crisis regulatory

reforms have raised the bar with respect to capital and liquidity requirements. The Landesbanken

have generally become more efficient, but the risk of inefficient use of public resources in some

institutions remains. For some Landesbanken, viable restructuring may require further downsizing,

opening of capital to private investors and further reform of governance structure. Chronic

overcapacity in the context of slowing international trade has put the shipping industry under

intense pressure. Further provisioning related to shipping may become necessary in banks with large

shipping exposures.

4

10. Consolidation is ongoing, albeit gradually. Banks have been reducing costs mainly

through reduction of branch networks and introduction of IT-based services. Among the largest

banks, Deutsche Bank announced a major shift in strategy, while Commerzbank is dealing with

legacy commercial real estate and shipping assets.

5

A merger of DZ Bank AG and WGZ Bank AG, two

central institutions for cooperative banks, will be effective in 2016 creating the country’s third-

largest bank by total assets and should lead to improved efficiency.

4

For several banks with shipping loan portfolios, these loans are large in proportion of capital and are concentrated

in the container segment with the biggest over-capacity. While parts of the legacy portfolios—arguably the riskiest

exposures—have been wound down, the ECB’s 2014 asset quality review (AQR) revealed that most of these banks

operated under optimistic cash-flow projections, requiring EUR 2 billion of additional provisioning for shipping loans

(30 percent of the total AQR capital effect for German banks in the sample). The AQR was undertaken before the

recent slowdown in global trade, fall in commodity prices and the ensuing increase in overcapacity.

5

Repeated fines for involvement in the systematic manipulation of benchmarks, misleading regulators, and violating

U.S. restrictions on conducting business with sanctioned countries, hit Deutsche Bank’s bottom line and may be

indicative of corporate governance issues.

877.6

153.5

103.9

540.5

837.1

596.1

486.7

140.4

102.4

0

400

800

1,200

1,600

2,000

Large commercial banks Savings banks Cooperative banks

Deposits of banks Deposits of non-banks Other Liabilities 1

/

1/Other liabilities include bearer debt securities, capital and reserves, and other liabilities.

Source: Deutsche Bundesbank

GERMANY

18 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 5. Germany: Systemic Risk Indicators

Global risk map changed… … while loose monetary conditions dominate in Germany.

*Components of drivers differ for GFSR and Germany risk maps.

Perceived riskiness of banks grew in early 2016… … while yield curve remains flat…

largest banks’ stocks underperform… … and market volatility has risen.

2. Emerg ing mark et ri sks

3. Credit risks

4. Market and liquidity

risks

5. Risk appetite

6. Monetary and financial

conditions

1. Macroeconomic risks

0

2

4

6

8

10

GFSR Risk Map

April 2016

April 2011

No te: Away fr om ce nt er sig ni fies highe r risk s, easier m one tary and

financial conditions

,

or hi

g

her risk a

pp

etit

e

.

2. Inward spillover risks

3. Credit risks

4. Market and liquidity

risks

5. Monetary and financial

conditions

6. Risk appetite

1. Macroeconomic risks

0

2

4

6

8

10

Germany Risk Map

2016Q1

2011Q1

No te: Away fr om ce nt er si gni fies hi gher r isk s, ea si er monetary and

financial conditions, or higher risk appetite

.

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

May-11 May-12 May-13 May-14 May-15 May-16

German Banks 5y CDS Spreads

(in pps)

Deutsche

Commerzbank

UniCredit

LBBW

DZBank

Source:Bloomberg

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

May-11 May-12 May-13 May-14 May-15 May-16

Banking Performance

(2011 = 100)

S&P500 Banks

FTSE 300 Banks

Deutsche Bank

Commerzbank

Source: Bloomberg

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

May-11 May-12 May-13 May-14 May-15 May-16

VDAX Index

(in pps)

VDAX

Expected fluctuations in DAX deriv.market for the following 45 days.

Source: Bloomberg

GERMANY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 19

B. Financial System Resilience

6

Banking Solvency Tests

11. Solvency tests covering all banks operating in Germany were performed to evaluate

the stability of the German banking system (Figures 6 and 7, Annex IV). The analysis covered

1776 institutions operating in Germany and assessed banks’ resilience to credit and market risk,

including foreign exchange rate and sovereign risk, equity price, and house price risk, in the baseline

based on the October 2015 World Economic Outlook and two stressed scenarios.

12. The German banking system would remain broadly stable under the baseline scenario.

7

Banks are relatively well capitalized, with CET1 ratios around 15 percent, on average, and found to

be resilient, with an improvement in their solvency levels under the baseline. For both large banks

(also known as significant institutions or SIs) and small and medium-sized banks (less significant

institutions or LSIs), interest revenue would continue to deteriorate, albeit more or less offset by

6

See the Technical Note on “Stress Testing the Banking and Insurance Sectors” for details.

7

The stress tests were performed against the end-2019 “fully-loaded” regulatory definitions, including applicable

buffers.

Figure 6. Germany: Macroeconomic Scenarios—Key Variables

Source: IMF Staff Calculations.

-10

-8

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Growth in Real GDP

(Percent, yoy)

Growth in real GDP

Baseline Sce nario

Global Stress Scenario (Adverse 1)

Euro Area Crisis Scenario (Adverse 2)

Global Financial Crisis (hypothetical)

90

95

100

105

110

115

-10123

Severity Comparison

(Real GDP Growth in Percent, yoy)

Global Financial Crisis (2008 = 100)

Baseline (2015 = 100)

Adverse 1 (2015 = 100)

Adverse 2 (2015 = 100)

Year

0

2

4

6

8

10

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Unemployment Rate

(Percent)

Unemployment rate

Baseline Scenario

Global Stress Scenario (Adverse 1)

Euro Area Crisis Scenario (Adverse 2)

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Consumer Price Inflation

(Percent)

Inflation

Baseline Scenario

Global Stress Scenario (Adverse 1)

Euro Area Crisis Scenario (Adverse 2)

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

Global Stress Scenario

(Adverse 1)

Euro Area Crisis Scenario

(Adverse 2)

Shocks to Sovereign Bond Yields

(Change in basis points)

EA periphery

EA core

US, UK, Japan

Duration risk premia shocks

80%

85%

90%

95%

100%

105%

110%

115%

120%

2015 2016 2017 2018

Change in House Prices

(Base=2015)

Baseline Adverse scenarios

GERMANY

20 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

lower interest expenses. Nevertheless, in the current low interest rate environment, business models

concentrating on maturity transformation continue to weigh on bank profitability.

8

13. Under the adverse scenarios, banks would see an increase in loan losses, while adverse

market price movements take a toll on trading income and the value of sovereign bonds. The

credit risk model implies that loan losses would rise by up to 80 percent, as a result of a rise in

default probabilities. Banks’ annual credit impairment needs would almost double, albeit from a very

low level, in part because of the impact of house prices stress on mortgage collateral values. SIs

would suffer a 40 percent drop in trading income, while LSIs with very little trading exposure and

open foreign exchange (FX) positions would be affected much less. The direction of net FX positions

varies across banks and, on average, the impact is not large. Some SIs are affected by credit risk and

sovereign bond valuation losses. LSIs mainly suffer from continuously falling net interest income,

and structurally high costs.

Under the Global Stress Scenario, the CET1 ratio of SIs would drop by 2.6 percentage points,

but remain above 10 percent. On aggregate, capital shortfalls amount to EUR 6.0 billion, or

0.2 percent of annual GDP. LSIs appear more resilient, and that group as a whole would

experience a drop in CET1 ratio of only around 0.3 percentage points against the fully-loaded

CET1 hurdle. The CET1 capital shortfall amounts to around EUR 450 million. Only 32 banks out of

1,755 in this bucket would see their CET1 capital ratios drop below fully-loaded regulatory

hurdle rates in 2018.

The EA Crisis Scenario would cause the average CET1 ratio to drop by 2.2 percentage points, to

12.7 percent in 2018 for SIs, corresponding to a capital shortfall of EUR 4.2 billion, or 0.1 percent

of annual GDP. LSIs would see CET1 ratio eventually rising 0.6 percentage points above the

current level, after a 0.2 percentage point drop, against the fully-loaded CET1 hurdle, including

buffers. The aggregate CET1 capital shortfall stands at around EUR 450 million, with 30 small and

medium-sized banks breaching the regulatory hurdles.

9

14. Sensitivity analysis shows that the persistently low interest rates weigh significantly on

the profitability of LSIs (Figure 8).

10

Under banks’ own interest rate projections, profitability is

expected to decline by around 25 percent by 2019. Should the low interest rates persist, operating

profit could slump by 50 percent, on average. If the interest rate were to fall by a further 100 basis

points, the operating profit of LSIs could decline by 60 percent or 75 percent, under a dynamic or

static balance sheet assumption, respectively.

8

The drop in bank profitability would not reduce the regulatory capital ratio as long as net after-tax profits remain

positive. As with the Bundesbank’s results, despite the impact on system profitability, the capital shortfalls in a few

individual banks were not sufficient to cause a decline in the aggregate capital ratios.

9

One-off effects are an important driver of the capital shortfall, in particular, non-recurring write-offs. In contrast to

the 2016 EU-wide bottom-up stress test of the European Banking Authority (EBA), such events in the base year (2015)

have not been removed from the balance sheet when profit and loss positions were projected three years (2016-

2018) into the future." See “2016 EU-wide stress test-Methodological note” for the EBA methodology.

http://www.eba.europa.eu/-/eba-launches-2016-eu-wide-stress-test-exercise.

10

See Bundesbank (2015), Survey on the Profitability and Resilience of German Credit Institutions in a Low-Interest-

Rate Setting. http://www.bundesbank.de/Redaktion/EN/Pressemitteilungen/BBK/2015/2015_09_18_bafin_bbk.html

GERMANY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 21

Figure 7. Germany: Solvency Stress Test

Source: IMF Staff Calculations.

Note: The top panel shows the evolution of CET1 ratio under the three scenarios. Capital shortfalls to regulatory hurdles are

shown as bars in the panel below, together with the share of total assets that the banks dropping below hurdle rates correspond

with (markers, rhs). The drivers are expressed in terms of percentage points of the CET1 ratio. For example, the credit risk losses

experienced by large banks in the Global Stress Scenario equal 2.3 percentage points of the CET1 ratio.

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

Global Stress Scenario Euro Area Crisis

Main Drivers of CET1 Ratio,

Large Banks

(in percent)

Dividends

Tax

RWA (unexpected loss)

FX gains/losses

Sovereign bonds valuation

gain/loss

Loan loss impairments (expected

loss)

Personnel and other expenses

Other income

Net trading income (w/o sovereign

valuation gains/loss)

Net fee and commission income

Net interest income

16.7

14.9

12.3

12.7

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

2015

2016

2017

2018

Baseline

Global Stress Scenario

Euro Area Crisis Scenario

Common Equity Tier 1 Capital

Large Banks

(in percent of RWA)

16.8

15.0

15.4

15.6

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

2015 2016 2017 2018

Baseline

Global Stress Scenario

Euro Area Crisis Scenario

Common Equity Tier 1 Capital

Small- and Medium-sized Banks

(in percent of RWA)

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

Global Stress Scenario Euro Area Crisis

Main Drivers of CET1 Ratio,

Small- and Medium-sized Banks

(in percent)

Dividends

Tax

RWA (unexpected loss)

FX gains/losses

Sovereign bonds valuation

gain/loss

Loan loss impairments (expected

loss)

Personnel and other expenses

Other income

Net trading income (w/o sovereign

valuation gains/loss)

Net fee and commission income

Net interest income

0

2

4

6

8

10

Baseline Global Stress

Scenario

Euro Area Crisis

Scenario

CET1 Capital Shortfall (EUR bn)

CETI Capital Shortfall below CET1 Minimum

Large Banks

(incl. CCB and OSII buffers)

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

Baseline Global Stress

Scenario

Euro Area Crisis

Scenario

CET1 Capital Shortfall (EUR bn)

CET1 Capital Shortfall below CET1 Minimum

Small- and Medium-sized Banks

(incl. CCB)

GERMANY

22 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 8. Germany: Low Interest Rates and Bank Profitability

Source: Bundesbank

Note: The charts show, for five different tests, the evolution of operating profit to total assets for some 1500 LSIs. The top-left

chart gives weighted averages for each scenario tested, while the other charts show the median and the 5

th

/95

th

percentile of

individual banks’ operating profit. Details about methodology, scenarios, and samples can be found in the Stress Test Matrix in

the Annex IV.

15. Sovereign risk analysis shows diversity across banks (Figure 9). While noticeable in some

banks, valuation losses from sovereign exposures tend to be rather low overall. Banks usually keep

more risky securities in the held-to-maturity portfolio, which is not being marked to market.

11

Also,

duration differs considerably across portfolios and banks. Banks with higher sovereign risk index

values hold longer-term or riskier paper, or try to generate profit from market movements in yields.

11

Analysis used the applicable regulatory standard under which held-to-maturity portfolio is not marked to market,

while for the available-for-sale portfolio, the prudential filter is being phased-out. Therefore, if banks had to mobilize

liquidity under stress, and sell securities in the banking book, losses would increase.

-25%

-50%

-10%

-75%

-60%

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

Overview

(Operating profit, in percent of total assets)

Banks' own projections

Low interest rate environment

+200bp shift (static)

-100bp shift (static)

-100bp shift (dynamic)

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

Banks' own projections (dynamic)

(in percent)

Median 5th percentile 95th percentile

-0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

Low interest rate environment (static)

(in percent)

Median 5th percentile 95th percentile

-0.6

-0.4

-0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

+200bp Shift (static)

(in percent)

Median 5th percentile 95th percentile

-0.6

-0.4

-0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

-100bp Shift (static)

(in percent)

Median 5th percentile 95th percentile

-0.4

-0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

-100bp Shift (dynamic)

(in percent)

Median 5th percentile 95th percentile

GERMANY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 23

Figure 9. Germany: Sovereign Exposures, Risk Index, and Valuation Losses under Stress

Source: IMF Staff Calculations using EBA 2015Q2 data.

Note: The sovereign risk index gives for each bank the valuation loss (VL) with the gross volume of sovereign bond exposures

held (Exp), relative to the total sample

If the index value is 1, the valuation loss corresponds to the total sovereign exposure held by the bank, signaling average risk

from sovereign exposures. If the value is above 1, the bank’s valuation loss is disproportionally higher than its holdings would

imply, indicating that the sovereign bond portfolio has relatively more risk (and vice versa). Index values are determined by (i) the

issuer’s risk as expressed by the sovereign yield and its volatility of time, (ii) average maturity of the bonds in the portfolio

together with (iii) the bank’s accounting of that exposure (HTM, AFS, FVO, HFT).

0

2

4

6

8

10

0

80

160

240

320

400

HTM AFS FVO HFT

Net Direct Exposures and Duration

(in EUR bn and Years)

Net direct ex

p

osure (lhs) Avera

g

e maturit

y

(rhs)

0

2

4

6

8

10

Scenario 1 Scenario 2

Valuation Loss

(in EUR bn)

0123

Aareal Bank AG

Bayerische Landesbank

Commerzbank AG

DekaBank Deutsche Girozentrale

Deutsche Apotheker-und Ärztebank eG

Deutsche Bank AG

Deutsche Zentral-Genossenschaftsbank AG

HASPA Finanzholding

HSH Nordbank AG

Hypo Real Estate Holding AG

Landesbank Baden-Württemberg

Erwerbsgesellschaft der S-Finanzgruppe

Landesbank Hessen-Thüringen Girozentrale

Landeskreditbank Baden-Württemberg–Förderbank

Landwirtschaftliche Rentenbank

Münchener Hypothekenbank eG

NORD/LB Norddeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale

NRW.BANK, Düsseldorf

VW Financial Services AG

WGZ BANK AG

Sovereign Risk Index

(in EUR bn)

Valuation Loss (EUR bn)

Sovereign risk index

11

ii

nn

jj

jj

VL Exp

Idx

VL Exp

GERMANY

24 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Bank liquidity tests

16. Tests based on the LCR show that the banks would be able to withstand market and

funding liquidity shocks (Figure 10). Almost all banks show ratios above 70 percent, and most

banks already today have LCR ratios above 100 percent, with foreign banks showing the lowest

dispersion.

17. Banks have been increasing both the LCR and the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR),

and larger banks appear to be managing their ratios more efficiently (Figure 11). Analysis of

detailed Basel Committee’s (BCBS) Quantitative Impact Study (QIS) results, reported by participating

banks, shows a general improvement in ratios since 2011, and the variation across banks’ LCRs has

also reduced over time.

Figure 10. Germany: LCR Estimates

(In percent)

Source: Bundesbank.

Note: Results were estimated from reporting data through a matching with CRD IV asset and liability categorization (i.e., net

outflows and liquid assets). The Whisker plots give the lower and upper quartile, the median (black line inside the box), and the

lower and upper 5 percent percentile. The orange line is the current (2016) regulatory minimum of 70 percent, while the dashed

line shows the fully phased-in hurdle rate of 100 percent. Outliers are not shown. Results for the four big banks are not shown,

as individual LCRs could be identified. However, they are all above 70 percent regulatory minimum. The big bank group includes

Commerzbank, Deutsche Bank, Deutsche Postbank, and UniCredit.

GERMANY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 25

Insurance solvency tests

18. Low interest rates pose particular challenges to life insurers over the medium- to long-

term, reflecting the predominance of traditional products with high guaranteed rates of

return (Figure 12). Capital adequacy ratios have been showing a downward trend in recent years.

Since 2016, Solvency II has created new pressures on life insurers to recognize the impact of low

interest rates in a forward-looking assessment of solvency. Some evidence of search for yield has

been emerging.

12

Health, property and casualty, and reinsurance companies appear to be more

robust, reflecting lower dependence on investment returns.

12

Together with rating migration effects, this exacerbates the challenge to meet Solvency II requirements as higher

capital must now be held against riskier assets. Evidence of search for yield includes increasing investment in non-

German sovereign bonds and higher risk investments (such as BBB) with longer duration.

Figure 11. Germany: LCR and NSFR Reported by German Banks in the BCBS QIS

Source: Bundesbank

Note: Results as reported by banks participating in BCBS QIS. The box gives the lower and upper quartile, the median is shown

as black line separating the box, the weighted average as orange circle, and whiskers are at the 5th and 95th percentile. For the

LCR, the orange line marks the 2016 regulatory minimum of 70 percent, while the dotted line gives the fully phased-in 2019

minimum of 100 percent. For the NSFR, the dotted orange line marks the future expected regulatory minimum of 100 percent,

to be introduced in 2018. Whiskers extending above the vertical axis’ range are removed.

GERMANY

26 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 12. Germany: Insurance Earnings, Solvency, and Risk Analysis

P&C and reinsurers maintain high Solvency Ratios, while

life insurers have the lowest ratios.

Publicly available Solvency II figures suggest that the end-

2014 ratio is a good proxy of the latest figure.

Fixed income portfolios are gradually shifting to lower

credit grades.

Modified duration o

f

fixed income

p

ortfolio of life

insurers have increased in the last 4 years.

Life insurers are making efforts to cope with lower

investment returns by reducing guaranteed rates and

policyholders’ bonuses.

Guaranteed rate and the duration of German life insurers

are some of the highest among EU countries.

Source: BaFin, Bundesbank, EIOPA, Insurer disclosures (Allianz, Munich Re, AXA and Generali), Assekurata, IMF Staff Calculations.

100 300 500 700 900 1,100

Life

P&C

Reinsurance

Solvency I Ratio

(in percent)

0 50 100 150 200 250 300

End 2014

End 2015

End Jan 2016

Solvency II SCR Ratio (Group Level)

(in percent)

Allianz Munich Re AXA Generali

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

2011 2012 2013 2014

Life Insurers: FI Portfolio Rating Distribution

High Yield BBB A AA AAA

03691215

AAA

AA

A

BBB

High

Yield

Total

Duration of Assets

(Year)

2011 2012 2013 2014

3.0

3.4

3.8

4.2

4.6

5.0

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Life Insurers' Key Interest Rates

(in percent)

Current Avg ROI (excl. gains from hidden reserves)

Net ROI

Guranteed Rate + Policyholders' Dividends

Avg Guranteed Rate in Life Insurers' Portfolios

AT

BE

DE

DK

ES

FI

FR

GB

IT

NL

PL

SE

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

0 4 8 12 16 20

Internal Effective Rate of Liabilities

Sensitivity of Liabilities

Liabilities Sensitivity and IRR

(in percent)

GERMANY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 27

19. Stress tests analyzed the impact of low interest rates under Solvency II (Annex V). The

scenarios covered major market shocks, while sensitivity analysis assessed the potential impact of

other insurance-specific risks, such as longevity and lapse risks. A majority of life insurers (93 percent

of the sector by assets) were covered. The methodology reflected the significance of policyholder

participation in traditional life insurance and the scope for insurers to reduce future policyholders’

profit participation in a stressed situation.

13

20. The results are stated with respect to the Solvency II Capital Requirement (SCR) ratio,

with and without transitional measures (Figure 13). Based on EU law, the so-called transitional

measures allow insurers, on BaFin’s approval, to mitigate material Solvency II impacts arising from

lower interest rates over the 16-year long phase-in period. Both ratios—with and without

transitional measures—will be published in 2017, the stress tests apply the two hurdle rates.

Figure 13. Germany: Insurance Stress Testing Results

SCR ratio with transition is above the minimum after

stress. Without transition, the majority of life insurers may

not be able to meet the requirement.

Spread and interest rate risks have material impacts, but

LAC_TP reduced the loss by more than 50 percent.

A

significant amount of potential loss absorption capacity

is embedded in the liabilities of life insurers.

Capital shortfalls might increase in a non-linear fashion.

Source: BaFin and IMF staff calculations

13

German life insurers recognize EUR 136 billion of future discretionary bonuses as part of their liabilities. In the

stress test, the future discretionary bonuses are assumed to be reduced by EUR 58 billion.

-100

0

100

200

300

400

500

Before - With

Transition

After - With

Transition

Before - Without

Transition

After - Without

Transition

SCR Ratio Distribution

(in percent)

75th Percentile Unweighted Avg. Weighted Avg. Median 25th Percentile

0

50

100

150

200

250

Net DTL Future Discretionary Benefits

Other own funds Reconciliation reserve

Surplus funds

Own Funds and Sources of Loss Absorption Capacity

(in EUR bn)

0

9

18

27

36

45

0 25 50 75 100 125

Capital Shortfall

Loss Amount

Loss and Capital Shortfall Relationship

(in EUR bn)

GERMANY

28 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

21. With transitional measures, insurers’ capital levels appear generally sufficient,

although a minority would have difficulties in meeting the SCR under stress. Life insurers

maintain SCR ratios above 100 percent even under stress, although the weighted average SCR ratio

drops from 372 percent to 236 percent. No firm would have negative capital after the shocks, but for

13 firms (out of 75) the SCR ratio would fall below 100 percent. The total capital shortfall by value

would be small.

22. Without the transitional measures, a majority of life insurers would have difficulties in

meeting the SCR. The weighted average SCR ratio would fall from 126 percent to 48 percent under

stress. Thirty-four firms and 58 firms (out of 75) would fall below the 100 percent SCR ratio before

and after the shocks, respectively. Eight firms and 27 firms would have negative capital before and

after the shocks, respectively. The total capital shortfall would be EUR 12 billion (0.4 percent of GDP)

before shocks and would increase to EUR 39 billion (1.3 percent of GDP) after the shocks.

23. The business model is a significant determinant of insurers’ relative resilience. The tests

were conducted at the legal entity level. Individual large insurers are generally more resilient than

others, as many are part of wider groups and benefit from diversification across business lines and

geographically. Many small firms have focused on protection-type business, where profitability is

less affected by the low interest rate environment and thus have exceptionally high SCR ratios, and

appear resilient to investment-side interest rate and other market shocks. However, some medium-

size life insurers are more vulnerable to the low interest rate environment and additional market

shocks. Features such as business mix, the amount of unrealized gains, future discretionary

policyholders’ bonuses, and average guaranteed rates are the most important risk drivers.

14

14

Most insurers that did not perform well in the test have already been on BaFin’s watch list and placed under

intensive supervision, such as enhanced reporting and more frequent on-site inspections, etc.

GERMANY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 29

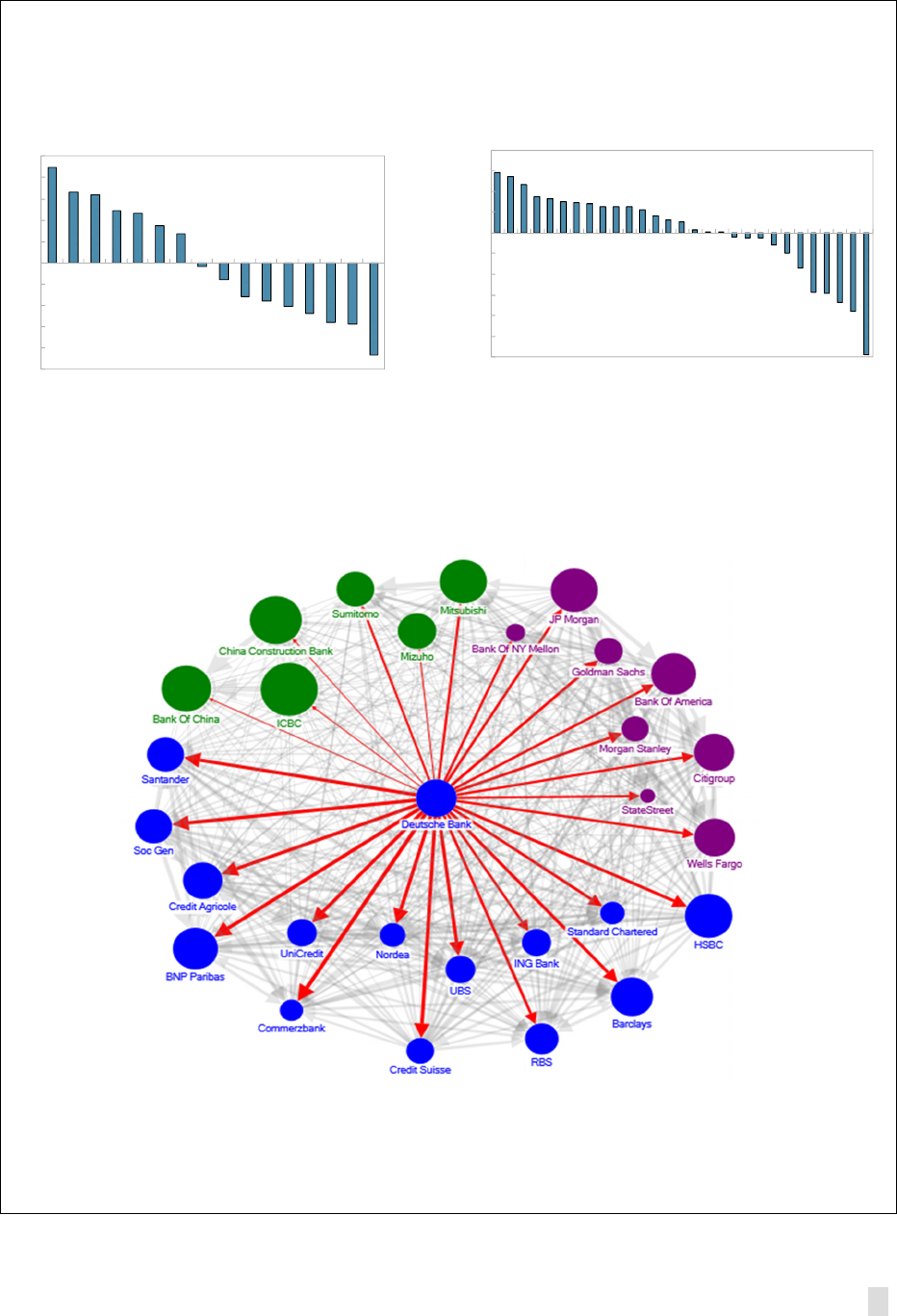

C. Systemic Risk and Spillovers

15

24. Domestically, the largest German banks and insurance companies are highly

interconnected (Figure 14). The highest degree of interconnectedness can be found between

Allianz, Munich Re, Hannover Re, Deutsche Bank, Commerzbank and Aareal bank, with Allianz being

the largest contributor to systemic risks among the publicly-traded German financials.

16

Both

Deutsche Bank and Commerzbank are the source of outward spillovers to most other publicly-listed

banks and insurers. Given the likelihood of distress spillovers between banks and life insurers, close

monitoring and continued systemic risk analysis by authorities is warranted.

25. Notwithstanding moderate cross-border exposures on aggregate, the banking sector

is a potential source of outward spillovers. Network analysis suggests a higher degree of outward

spillovers from the German banking sector than inward spillovers.

17

In particular, Germany, France,

the U.K. and the U.S. have the highest degree of outward spillovers as measured by the average

percentage of capital loss of other banking systems due to banking sector shock in the source

country. Reflecting solid aggregate capital buffers, the impact of inward spillovers on the German

banking sector is considerably more moderate, as measured by the percentage of capital loss in the

banking system due to the default of all exposures.

26. Among the G-SIBs, Deutsche Bank appears to be the most important net contributor

to systemic risks, followed by HSBC and Credit Suisse (Figure 15). In turn, Commerzbank, while