Primary Care Prescribing

REPORT BY THE COMPTROLLER AND AUDITOR GENERAL

27 November 2014

Primary Care Prescribing

Published 27 November 2014

This report is being published under Article 8 of the Audit (Northern Ireland) Order 1987 for presentation

to the Northern Ireland Assembly in accordance with Article 11 of that Order.

K J Donnelly Northern Ireland Audit Office

Comptroller and Auditor General 27 November 2014

The Comptroller and Auditor General is the head of the Northern Ireland Audit Office employing some

145 staff. He and the Northern Ireland Audit Office are totally independent of Government. He certifies

the accounts of all Government Departments and a wide range of other public sector bodies; and he

has statutory authority to report to the Assembly on the economy, efficiency and effectiveness with which

departments and other bodies have used their resources.

For further information about the Northern Ireland Audit Office please contact:

Northern Ireland Audit Office

106 University Street

BELFAST

BT7 1EU

Tel: 028 9025 1100

email: info@niauditoffice.gov.uk

website: www.niauditoffice.gov.uk

© Northern Ireland Audit Office 2014

Primary Care Prescribing

Contents

Contents

Executive Summary 1

PART 1: Background and Scope of Report 7

In Northern Ireland, the Health and Social Care Board contracts external

providers to supply pharmaceutical services to the public 8

In 2013 community pharmaceutical services cost £460 million and CPCs

dispensed almost 39 million prescription items 8

High level comparison of the number and cost of prescriptions elsewhere in

the United Kingdom indicates that there is potential for improving cost effective

prescribing in Northern Ireland 9

Purpose and Scope of our review 14

PART 2: Community Pharmacy Contractors’ Reimbursement 15

Over time, the number of pharmacy outlets in Northern Ireland has risen while

the number of CPCs has fallen 16

Northern Ireland CPCs dispense more prescriptions per head of population

than those in England and Scotland 17

In 2012-13 CPCs received £460 million for providing community

pharmaceutical services 18

Reimbursement costs are the most significant element of the funding package 19

The majority of reimbursement costs each year relate to ‘branded’ drugs 19

NI reimbursement rates for dispensing certain ‘generic’ drugs were based

on the Scottish Drug Tariff but this led to legal challenge 19

The legal action has cost the Department £550,000 CPCs received

compensation of some £6 million. A further £40 million was made available

to CPCs over the seven year period to 2011 23

Part 3: Trends in General Practitioner (GP) Prescribing Practice 25

The volume of prescribed drugs has increased at a steady rate over recent

years but costs have fallen substantially since 2010 27

Primary Care Prescribing

Contents

There have been a range of influences which have helped to contain the

cost of primary care prescribing 29

HSC Board Medicines Management Advisors have been instrumental in

ensuring prescribing efficiencies are generated 30

British National Formulary (BNF) 31

The use of an ‘unclassified’ category prevents comprehensive analysis

of prescribing patterns 33

Variations in regional prescribing rates which cannot be fully explained by

differences in population demographics suggests that it may be possible to

improve the quality of prescribing further 35

Part 4: The Scope for More Efficient and Effective Prescribing 39

The Department, HSC Board and GPs are to be commended for the savings

generated from improving the rate of generic prescribing 41

There is wide variation in the cost of prescribing per head of population

across individual GP practices locally 42

There is scope to make further savings from prescribing without affecting

patient care 44

Earlier switching to cheaper generic stomach acid treatments (Proton Pump

Inhibitors (PPI)) would have resulted in additional efficiency savings of

£2.2 million in 2012 and £1 million in 2013 45

Switching to less expensive statins would have saved around £2.7 million

in 2012 and £2.5 million in 2013 47

Earlier switching to alternative generic drugs in the treatment of depression

would have resulted in additional efficiency savings of £2.7 million in

2012 and £1.6 million in 2013 51

More money is spent prescribing Pregablin in NI than on any other drug.

Pregablin is more frequently prescribed in NI than elsewhere in the UK 55

Appendices 59

Appendix 1: Generic Drug Categories 60

Appendix 2: Legal challenge to new Drug Tariff 61

Primary Care Prescribing

Abbreviations

ABPI Association of British Pharmaceutical Industry

APP Annual Professional Practice Allowance

BNF British National Formulary

BSO Business Service Organisation

CoSI Cost of Service Investigation

CPC Community Pharmacy Contractor

CPNI Community Pharmacy Northern Ireland

DHSSPS Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety

GMS General Medical Services

GP General Practitioner

HSC Health and Social Care

HSCB Health and Social Care Board

JR Judicial Review

LDL Low Density Lipoprotein

MMA Medicines Management Adviser

NAO National Audit Office

NHS National Health Service

NI Northern Ireland

NIAO Northern Ireland Audit Office

NICE National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence

PCC Pharmaceutical Contractors Committee

PCEP Pharmaceutical Clinical Effectiveness Programme

PIS Prescibing Incentive Scheme

PPI Proton Pump Inhibitor

PPRS Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme

PU Prescribing Unit

QOF Quality and Outcomes Framework

RIA Regulatory Impact Assessment

UK United Kingdom

WTE Whole Time Equivalent

Primary Care Prescribing

Contents

Glossary of terms

Association of British

Pharmaceutical

Industry (ABPI)

Represents biopharmaceutical companies and is recognised by government

as the industry body negotiating on behalf of the branded pharmaceutical

industry for statutory consultation requirements including the pricing scheme for

medicines in the UK.

British National

Formulary (BNF)

A joint publication of the British Medical Association and the Royal

Pharmaceutical Society. It aims to provide prescribers, pharmacists, and other

healthcare professionals with sound, up-to-date information about the use of

medicines.

Community Pharmacy

Contractor (CPC)

Dispenses health service prescriptions after application and acceptance

onto the Health and Social Care pharmaceutical list. Applications can be

made by registered pharmacists or non-pharmacists, partnerships or bodies

corporate, as long as a registered pharmacist is employed.

The Comprehensive

Spending Review

(CSR)

The Comprehensive Spending Review sets out the Government’s objectives

and priorities and allocates resources accordingly.

Cost of Service Inquiry

(COSI)

Identifies and quantifies the various NHS costs involved in delivering

community pharmacy services.

Generic drugs

A pharmaceutical product no longer protected by a patent which can be

copied by other companies. It may be marketed either under its own brand

or as an unbranded product. Generic drugs are frequently as effective as,

but much cheaper than, brand-name drugs, because their manufacturers do

not incur the risks and costs associated with the research and development of

innovative medicines.

Generic Prescribing

Current policy is that generic medicines should be prescribed in all

appropriate circumstances. It is considered that around 75 per cent of

medicines can be dispensed generically.

Judicial Review

A process by which the courts review the lawfulness of a decision made (or

sometimes lack of a decision made) or action taken (or sometimes failure to

act) by a public body. A judge considers whether a public body has acted in

accordance with its legal obligations and if not, can declare a decision taken

by it invalid.

Local Commissioning

Groups (LCGs)

There are five Local Commissioning Groups in Northern Ireland (Belfast,

Northern, South Eastern, Southern and Western). LCGs are committees of the

Health and Social Care Board and are responsible for commissioning health

and social care for their local population. They also have responsibility for

planning and delivering health and social care to meet assessed needs.

Primary Care Prescribing

Medicines Management

Advisers (MMAs)

Pharmacists employed by the Health and Social Care Board who work

with GP surgeries in order to support the safe effective and efficient use of

medicines in primary care.

Prescription Item

A medicine, appliance or device written by a practitioner onto an appropriate

prescription form.

National Institute

for Health and Care

Excellence (NICE)

An executive non departmental public body of the Department of Health in

the United Kingdom. NICE provides guidance on current best practice in

health and social care, including public health, to the NHS in England and

Wales. All NICE guidance published since 1 July 2006, is reviewed locally,

for its applicability to Northern Ireland and, where applicable, is endorsed

for implementation.

Community Pharmacy

Northern Ireland

(CPNI)

The local representative body for community pharmacist contractors provide

services under the National Health Service in Northern Ireland. It negotiates

on services, the pharmacy contract and remuneration and reimbursement

with the Health and Social Care Board and the Department of Health, Social

Services and Public Safety.

Pharmaceutical

Clinical Effectiveness

(PCE)

A systematic approach to rational product selection and use, consistently

applied across secondary and primary care, taking account of clinical

need, evidential product clinical performance, product presentation, safety

characteristics and economic factors. The process can be applied to

medicines, wound care and medical and surgical disposable products.

Pharmaceutical Price

Regulation Scheme

(PPRS)

A non-contractual, 5 year, voluntary scheme between UK Government and

Industry covering all the relevant key issues that underpin the pricing of the

majority of NHS branded medicines.

Northern Ireland

Prescribing Units

(NI-PU)

Weight individual General Practitioner (GP) practices or Local Commissioning

Groups’ populations for age, gender and need to enable comparison of

prescribing patterns. The figures are based on cost of prescribing across all

therapeutic areas. The cost based weightings are standardised (based on a

female aged 5-15). Comparisons can therefore take account, for example, of

the greater needs of elderly people and of people living in deprived areas or

whose socio-economic circumstances mean they have higher than NI average

need for prescribing resources.

Regulatory Impact

Assessment (RIA)

A detailed and systematic appraisal of the potential impacts of a new

regulation. New regulations should only be introduced when other

alternatives have been considered and rejected and where the benefits justify

the costs.

Executive Summary

1. Most health service drug expenditure is

incurred in primary care where General

Practitioners (GPs) prescribe medicines

or treatments to address the clinical

needs of patients. The role of GPs in

deciding how resources should be spent

on these drugs is, therefore, key. Patient

consultations with GPs have increased

by almost 22 per cent over the six year

period to 2013-14. The trend in rising

patient consultations with GPs is likely to

continue due to the following drivers:

• Like all UK regions the population of

older people is increasing

1

;

• Poor lifestyles are a threat to

population health particularly in

lower socioeconomic groups;

• Overuse, sub optimal use and abuse

of prescription medicines; and

• Pharmaceutical innovation and

medical advances.

2. Decisions on which medication or

treatment is prescribed rests with the

GP and these decisions are highly

regulated and controlled. However,

patients’ requests and expectations

(and prescribers’ perceptions of these)

2 Primary Care Prescribing

Executive Summary

can influence prescribing behaviour.

Further, the decision on whether or not

to consume prescribed medication rests

with the patient.

3. Once in receipt of a prescription,

the patient takes it to a Community

Pharmacy Contractor (CPC)

2

. The

CPC dispenses the drug in question,

currently at no charge to the patient.

CPCs are responsible for purchasing the

drugs either directly from manufacturers

or through wholesalers. They are

subsequently reimbursed by the Health

and Social Care (HSC) Board for the

cost of these drugs.

4. In 2013 CPCs received almost

£460 million for providing community

pharmaceutical services, which included

reimbursement

3

of £381 million for

dispensing almost 39 million items

prescribed by GPs.

5. This report demonstrates that demand for

primary care medicines is characterised

by a particularly complex and unique set

of relationships, in which:

• Patients neither decide nor directly

pay (currently) for the medicines they

consume;

1 Office of National Statistics, National Population Projections, 2012-based Statistical Bulletin

2 The Health and Social Care (HSC) Board is legislatively required to make arrangements for the provision of community

pharmaceutical services in Northern Ireland. In practice, it contracts out these services to Community Pharmacy Contractors

(CPCs). In 2014, the HSC Board had contracts with 225 CPCs who dispensed prescriptions from 535 pharmacies.

According to Office of Fair Trading (Evaluating the Impact of the 2003 OFT Study on the Control of Entry Regulations in the

Retail Pharmacies Market (March 2010)); NHS Information Centre, (General Pharmaceutical Services in England, 2001-

2002 to 2010-2011 (November 2011)), the combined share of this market among the larger multiples and supermarkets

is now estimated to be slightly over 50 per cent.

3 Traditionally arrangements for reimbursing NI CPCs followed those in place elsewhere in the UK. However, new contractual

arrangements which were adopted in England, Wales and Scotland were rejected by NI CPCs and they subsequently

legally challenged the continued reliance on the UK Drug Tariff in NI. The legal challenge was upheld. Subsequent

negotiations failed to find a resolution and NI CPCs again took legal action. Again the legal challenge was upheld. No

resolution has yet been found and negotiations continue.

Primary Care Prescribing 3

• GPs decide which medicines should

be used but are not responsible

for the cost of what they prescribe;

whereas

• the HSC Board pays for medicines

by reimbursing pharmacies

for dispensing them but is not

responsible for deciding which

medicines are to be prescribed.

6. Against the background of these

relationships, the main thrust of this report

is that more rational prescribing by

GPs can achieve significant economies

in drug expenditure and release

money from within the drugs budget

without compromising patient care. It

is acknowledged that between 2006

and 2013, the cost of prescribing was

reduced in real terms by 18 per cent.

7. As the drugs budget is spent

predominantly by GPs, the HSC Board

does not directly control prescribing

behaviour. Moreover, the prescribing

decisions GPs make can be affected

by a range of factors, such as patient

need, clinical guidance, access to good

information and the marketing activities

of the pharmaceutical industry

4

. A key

challenge for the Board, therefore, is

to effectively influence the prescribing

behaviour of GPs.

8. We acknowledge the key role played

by the Board’s Medicine Management

Advisers (MMAs) in instigating and

facilitating change through the promotion

of more rational, safe, economic

and effective prescribing among GP

practices. While MMAs have little

power to compel doctors to prescribe

in a particular way, they have had

considerable success in working

alongside GP practices to facilitate

change and generate savings in the

prescribing budget. For instance, while

the volume of prescriptions increased

by around 5 per cent between 2010

and 2012, the cost of prescribing these

drugs has decreased by just over 7 per

cent in the same period. Commendably,

one of the reasons for the reduction in

costs is that generic prescribing rates

have improved considerably in NI over

recent years and are now on a par

with levels elsewhere in the UK. Also,

the variations between practices have

reduced significantly over the period

2010 to 2013.

9. The report draws particular attention to

the continuing variations shown by data

on prescribing activity and prescribing

expenditure, both between GP practices

locally and with their peers in other

parts of the UK using national data. We

found variations in the volumes and cost

of prescribing which did not appear to

match variations in indicators of clinical

need, such as disease prevalence.

The HSC Board regard Quality and

Outcomes Framework (QOF) data on

disease prevalence as extremely useful

4 House of Commons Health Committee, The Influence of the Pharmaceutical Industry, 5 April 2005.

4 Primary Care Prescribing

Executive Summary

for assessing clinical need and planning

service development. However, the

Department considers that the use of

QOF data in reaching any conclusion

on relative need between populations

is erroneous. It told us it had been

advised by the Northern Ireland Statistics

and Research Agency and the Health

and Social Care Information Centre in

England that QOF data is unsuitable as

a measure of need in this context. Our

report stresses the importance of the

HSC Board and GPs using all available

sources of relevant data to support

the benchmarking of GP practices in

identifying prescribing patterns which are

significantly different between peers and

which warrant further examination.

10. We acknowledge that high-level

prescribing cost comparisons with the

other UK regions have to be drawn with

great caution. In the Department’s view,

such comparisons are deeply flawed

given the differences in data definitions

and prescribing practices within the

jurisdictions. However, available national

statistics would suggest that if prescribing

expenditure here had been in line with

that in Wales in 2013, costs would

have been reduced by £73 million.

The Department does not accept that

these statistics are a measure of relative

efficiency and would not support the

view that costs could be reduced by

£73 million, as in its view, the statistics

do not compare jurisdictions on a like for

like basis.

11. More pertinent are the large variations

we found in prescribing costs between

local GP practices after standardising

their caseloads, meaning that there

is scope for GP practices to improve

efficiency, without affecting clinical

outcomes. As a result, we estimated

that, in 2013, potential savings of £19

million could have been realised if all

GP practices had achieved at least the

standard of the average practice. We

recognise that it will be challenging for

GPs to achieve all such potential savings

given that the savings need to be made

across a wide range of prescribed

drugs. The department has commented

that such estimates are crude and do not

take into consideration the other factors

associated with prescribing such as

access to other services; the impact of

cross-border workers; private healthcare.

The Department considers that there

will always be a degree of variability

between GP practices and therefore the

full quantum of such efficiencies will not

be realisable.

12. We also examined three groups of drugs

used to treat conditions for which there

are several suitable drugs available

at differing prices. We found large

variations in the extent to which local GP

practices prescribed lower cost drugs in

comparison to GP practices in the rest

of the UK. We also examined use of the

drug which has incurred the highest cost

in NI in the last number of years. We

calculated that the opportunity cost to

health and social care services here of

Primary Care Prescribing 5

not meeting UK levels was £17 million in

2012 and £15 million in 2013.

13. Potential economies may also be

achievable in other areas. For example,

research published in England estimated

that NHS primary and community care

prescription medicines waste cost £300

million. This indicates that an estimated

£18 million may be lost every year in

Northern Ireland in wasted prescriptions.

However, we have been advised

by the Department that while there is

potential waste, the interventions needed

to address this issue would offset the

potential savings. It is also important

to note that this is not in addition to the

monies referred to above. There may

also be potential for generating further

savings by reducing the number of

prescriptions for drugs of limited clinical

value or drugs which are not clinically

necessary. In this report we looked at

the potential for generating savings

by moving from off-patent branded

medicines to much cheaper generic

equivalents.

6 Primary Care Prescribing

Executive Summary

Part One:

Background and Scope of Report

8 Primary Care Prescribing

Part One:

Background and Scope of Report

In Northern Ireland, the Health and

Social Care Board contracts external

providers to supply pharmaceutical

services to the public

1.1 The Health and Social Care (HSC)

Board

5

is legislatively required to

make arrangements for the provision of

community pharmaceutical services in

Northern Ireland. These services include

dispensing those drugs prescribed

by General Practitioners (GPs)

6

. In

practice, it contracts out these services

to independent, retail pharmacy-outlet

owners (known as Community Pharmacy

Contractors (CPCs)).

1.2 CPCs can be registered pharmacists,

non-pharmacists, partnerships or bodies

corporate (providing a registered

pharmacist is employed in each

pharmacy outlet). In 2014, the HSC

Board had contracts with 225 CPCs

to provide community pharmaceutical

services from 535 pharmacies.

1.3 In 2014, 51 per cent of NI Pharmacies

were small independent businesses, 30

per cent operated in local partnerships

and the remainder, 19 per cent, formed

part of UK or multi-national groups.

In 2013 community pharmaceutical

services cost £460 million and

CPCs dispensed almost 39 million

prescription items

1.4 In Northern Ireland, in 2013, almost

39 million items prescribed by GPs,

were dispensed by CPCs. That year,

funding to CPCs for providing community

pharmaceutical services amounted

to £460 million. This represents

approximately 10 per cent of the total

spend on health and social care in

Northern Ireland.

1.5 Research published by York Health

Economics consortium in An Evaluation

of the Scale, Causes and Costs of Waste

Medicines reported that in England NHS

primary and community care prescription

medicines waste cost £300 million.

This indicates that a level of £18 million

may be lost every year in Northern

Ireland in wasted prescriptions

7

. This

estimate reflects patients’ failure to take

appropriate medicine which in turn

impacts on:

• the patient – who may not see an

improvement in their condition or

whose health may deteriorate;

5 Under Article 63 of the Health and Social Services (NI) Order 1972.

6 GPs are medically-qualified doctors with responsibility for attending to the everyday medical needs of a community. They

operate in the primary care sector. In Northern Ireland, the term ‘primary care’ refers to any of ‘the many forms of health

and social care and/or treatment accessed through a first point of contact provided outside hospitals’. Treatment provided

in a hospital setting is referred to as ‘secondary care’.

7 NI Direct website – Health and Well-being.

Primary Care Prescribing 9

• the HSC Budget – which could

re-direct resources within the HSC

sector; and

• the pharmaceutical industry –

which may struggle to prove the

effectiveness of new and innovative

drugs through post-marketing

surveillance.

1.6 Since 2010-11, the Department and the

Health and Social Care (HSC) Board

ran an annual ‘Don’t Use It, Don’t Order

it’ prescriptions medicines wastage

advertising campaign. In 2013-14, the

campaign included a new message

‘Wasting Medicines Wastes Money’

with the aim of influencing patients’

attitudes and behaviours to prevent

over-ordering of repeat prescription

medicines.

1.7 However, we have been advised

by the Department that while there is

potential waste, the interventions needed

to address this issue could offset the

potential savings. Since a proportion of

medicines waste is therefore inevitable,

complementary measures which improve

the quality and safety of prescribing are

required. We welcome the introduction

of such initiatives which have the

potential to reduce expenditure.

High level comparison of the number

and cost of prescriptions elsewhere

in the United Kingdom indicates that

there is potential for improving cost

effective prescribing in Northern

Ireland

1.8 The number of items prescribed has

increased in each region of the United

Kingdom (UK) over the seven year

period to 2013. Figure 1 shows that

Wales has consistently prescribed more

items per head of population that any

other UK region. Prescribing levels in NI,

although lower than those in Wales have

been higher than levels in England and

Scotland in each of the last seven years.

Levels in England and Scotland are very

similar.

10 Primary Care Prescribing

Part One:

Background and Scope of Report

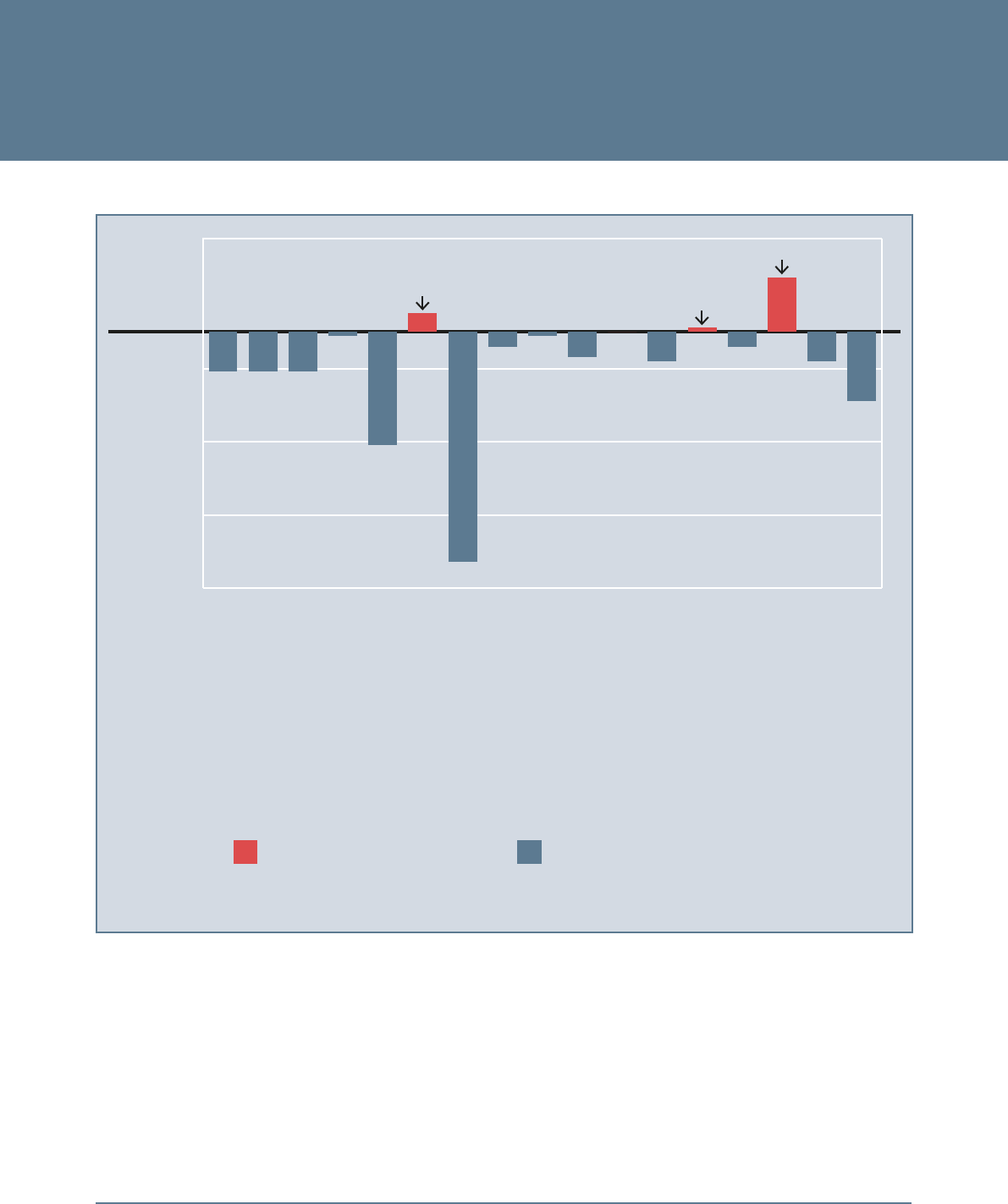

Figure 1: Number of items prescribed per head of population in the UK over the period 2007-2013

Source: Business Services Organisation – Prescription Cost Analysis Reports

8

1.9 Figure 2 compares the cost of

prescribing per head of population in

England, Scotland, Wales and NI over

the seven year period to 2013. Overall,

England has consistently had the lowest

cost per head of population in each

year since 2007. There are, of course,

regional variations across England.

For example, the number of items

prescribed per head of population in the

North East of England is 50 per cent

greater than the number in the South of

England. Costs in Scotland and Wales

are broadly similar, higher than those

in England but less than those in NI.

NI has had the highest cost per head

of population since 2007 and is the

only region in which costs per head of

population are higher in 2013 than they

were in 2007.

12

15

18

21

24

27

2013201220112010200920082007

Number of items per person

England

Northern Ireland

Scotland

Wales

8 Mid year population figures for 2012 were used as the 2013 population statistics were not available at the time of

publication.

Primary Care Prescribing 11

Figure 2: Prescribing cost per head of population

Source: Business Services Organisation – Prescription Cost Analysis Reports

0

50

100

150

200

250

2013201220112010200920082007

Cost per head of population £

England Wales Northern IrelandScotland

2007 2010 2013

NI

£221.09 £243.94 £223.54

England

£162.95 £167.82 £160.12

Scotland

£187.92 £192.25 £183.73

Wales

£196.37 £193.05 £182.96

12 Primary Care Prescribing

Part One:

Background and Scope of Report

1.10 It is important to remember that this

form of high level analysis, while

demonstrating trends over time, does

not take account of definitional or

organisational differences across

regions. However, using these

comparative statistics as a very basic

measure of relative efficiency, the

variation in prescribing costs here

compared with other UK countries

provides some evidence that it is

possible for local GPs to prescribe less

expensively. For example, if prescribing

costs had been in line with those in

Wales in 2013, overall prescribing

costs could have been reduced by £73

million.

1.11 The Department does not accept that

these statistics are a measure of relative

efficiency across the UK and would not

support the NIAO view that costs could

be reduced by £73 million if prescribing

costs here were in line with Wales. In

its view, the statistics do not compare

jurisdictions on a like for like basis: for

example, the Department told us that

they do not take account of variations

in the ratio of community to hospital

prescribing that exist across jurisdictions.

In England in 2012, 63.5 per cent of

total medicines expenditure took place in

the primary care setting, the comparable

figure here was 72.7 per cent.

1.12 We acknowledge that prescribing

arrangements can differ between the

four countries: for instance, outpatients

who are prescribed drugs by consultants

here will have that prescription filled out

by their GP; in England, by contrast,

such a prescription will be dispensed by

the hospital and therefore will not be a

charge on the primary care budget.

1.13 As a result, we recognise that it

will be important to account for the

precise differences in the prescribing

patterns of GPs here when comparing

them with elsewhere in the UK. This

basic comparison, which is based on

published data, points up the need

for a comprehensive examination of

the cost implications of prescribing in

order to explore and implement specific

measures to promote more cost-effective

prescribing patterns among local GP

practices. Our study looks in more detail

at this in Part 4.

1.14 In addition to variations in prescribing

arrangements, the higher cost of

prescribed medicines in primary care in

Northern Ireland is due to, for example:

• progress in achieving savings

through generic, rather than

branded, prescribing has been

slower here than elsewhere in the UK

(see paragraph 4.5);

Primary Care Prescribing 13

• unlike the other UK regions, the

introduction of new drugs was not

as tightly controlled here, therefore

the prescribing of newer, and usually

more expensive drugs (including

generics) can be more widespread

in NI; and

• secondary care (hospital) prescribing

practice has more impact on GP

prescribing practices in NI than

elsewhere in the UK .

The Department has advised us that

it does not accept the final two bullet

points.

1.15 The Department told us that prior to

2004, the approach taken to reducing

medicines expenditure had been to

focus on the costs and seek to deliver a

range of cost cutting initiatives. However

an exclusively financial focus can have

far reaching consequences in respect

of quality, safety and well being of

patients. This has been borne out in

recent times in the Francis Report into the

Mid -Staffordshire Trust. A sole financial

focus in the management of medicines

has only limited success and does not

address the challenge of optimising

the outcomes for patients through the

use of prescribed medicines. Since

2004, medicines optimisation policy in

Northern Ireland has been predicated

on quality and safety improvement

delivering improved health outcomes and

realised efficiencies. Such an approach

addresses value for money requirements

in addition to important medicines

optimisation principles including:

• Rationality Attention to the

evidence base for the prescribing of

medicines;

• Safety Address avoidable

medication related errors and

adverse incidents;

• Individuality Optimise outcomes for

individual patients;

• Equity Ensuring equality of provision

across the population, therapeutic

conditions and new medicine;

• Consistency Prescribing practice that

conforms to acceptable standards;

• Continuity Optimised medicines

outcomes across sectors and

professional groups; and

• Innovation Removing barriers to

continuous quality improvement.

14 Primary Care Prescribing

Part One:

Background and Scope of Report

Purpose and Scope of our review

1.16 This report looks at the value for money

of primary care drugs prescribing and

dispensing:

• Part 2 considers the arrangements for

reimbursing CPCs;

• Part 3 looks at trends in GP

prescribing, the volume of

prescriptions and the cost pressures

on the prescribing budget; and

• Part 4 examines the potential for

further cost savings.

1.17 The report does not examine secondary

care (hospital) prescribing or quantify

its impact on primary care prescribing.

It is important to note, however, that

secondary care prescribing decisions

often impact on primary care prescribing

decisions and costs (see paragraph

3.2). Further, this report does not

consider in detail the potential for

generating savings by reducing drug

wastage.

Part Two:

Community Pharmacy Contractors’ Reimbursement

16 Primary Care Prescribing

Part Two:

Community Pharmacy Contractors’ Reimbursement

Over time, the number of pharmacy

outlets in Northern Ireland has risen

while the number of CPCs has fallen

2.1 In 2012, the HSC Board had contracts

with 243 CPCs to provide community

pharmaceutical services (including

dispensing health service-prescribed

medicines) from 547 pharmacies.

Twelve years ago, 320 CPCs were

contracted to provide services in 509

pharmacies in Northern Ireland (see

Figure 3). Therefore, over time, while the

number of pharmacy outlets increased,

the number of CPCs decreased by

almost 25 per cent. The Department told

us that in 2014, the HSC Board had

contracts with 225 CPCs to provide

community pharmaceutical services from

535 pharmacies.

Number of Pharmacies

Number of Contracted Providers

Pharmacies Contracted Providers

500

510

520

530

540

550

201220112010200920082007200620052004200320022001

200

220

240

260

280

300

320

340

Figure 3: The number of providers contracted to provide pharmaceutical services and the total number of

pharmacies over the period 2001 to 2012

Source: The Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety

Primary Care Prescribing 17

Northern Ireland CPCs

dispense more prescriptions

per head of population

than those in England and

Scotland.

2.2 Northern Ireland has a lower average

population per service provider than

England and Wales. The average

number of prescriptions dispensed by

service providers in Northern Ireland

is higher than those in England and

Scotland but lower than Wales. Figure

4 provides comparative figures.

Figure 4: UK Comparative Pharmacy Information -2013

Northern

Ireland

England Scotland Wales

Population Estimate (millions)

1.8 53.9 5.3 3.1

Total Service Providers

547 17,823 1,580 1,067

Total Prescriptions (millions)

38.7 1,003.8 97.7 76.2

Number of Service Providers/1000 population

0.30 0.33 0.30 0.34

Average population per service provider

3,291 3,024 3,354 2,905

Average prescriptions per service provider

70,750 56,320 61,835 71,415

Prescriptions per head of population

21.50 18.62 18.43 24.58

Source: Business Services Organisation

Notes: Data is for calendar year 2013 with exception of England which is only available as financiaL year 2012-13

Total Prescription Items includes items dispensed by community pharmacies, appliance contractors and dispensing doctors

Service provider refers to Pharmacies, Appliance Contractors and Dispensing GPs (i.e. individual GPs not

Dispensing Practice)

18 Primary Care Prescribing

Part Two:

Community Pharmacy Contractors’ Reimbursement

2.3 In looking at the numbers of pharmacies

for each population it is worth

considering the issue of access to

services for service users. Pharmacies

in NI offer some, or all, of the following

examples of services:

• minor ailments scheme;

• smoking cessation scheme;

• medicines management services;

• medicines use reviews;

• repeat dispensing services;

• oxygen supply;

• emergency hormonal contraception;

• Helicobacter Pylori testing;

• supply of palliative medicine (out of

hours);

• measuring and fitting of hosiery

garments;

• supply of substitution medicines to

addicted persons;

• needle exchange schemes; and

• receipt and disposal of unwanted

medicines.

2.4 Pharmacists are often the first port of

call for sick persons seeking advice or

treatment of minor ailments and are able

to refer patients with more serious injuries

to the appropriate treatment channels.

Some pharmacies also offer services

such as blood sugar testing, cholesterol

testing, blood pressure measurement,

body mass index measurements

and weight management schemes

which do not form part of contractual

arrangements.

2.5 Contracts are regulated by the Control

of Entry Regulations which set out the

criteria which must be met before the

HSC Board can commission a CPC to

provide pharmaceutical services. There

are currently no established legislative

mechanisms or processes in place to

either remove commissioned CPCs who

continue to meet the relevant criteria from

the pharmaceutical list or to reduce the

overall number of contracts. However,

the Department and the HSC Board

are currently undertaking a Needs

Assessment to identify areas of under

or over provision of pharmaceutical

services in Northern Ireland.

In 2012-13 CPCs received £460

million for providing community

pharmaceutical services

2.6 CPCs attract a range of funding for

the services they provide on behalf

of the HSC Board. In 2012-13, just

under £460 million was paid to CPCs.

Figure 5 provides a breakdown of the

various elements of the 2012-13 funding

envelope.

Primary Care Prescribing 19

Reimbursement costs are the most

significant element of the funding

package

2.7 The most significant element of CPC

funding relates to reimbursement for

purchasing and dispensing drugs.

During 2012-13, reimbursement fees to

pharmacists amounted to £381 million

(see Figure 5).

The majority of reimbursement costs

each year relate to ‘branded’ drugs

2.8 About 70 per cent of the reimbursement

cost in 2012-13 related to the supply of

‘branded’ drugs – drugs still protected

by patent and known by the trade

name given by the manufacturer. While

branded drugs account for nearly 70

per cent of reimbursement costs, they

only account for about 30 per cent

of the total volume of items dispensed

each year.

2.9 Reimbursement levels for branded

drugs are determined by the published

list price

9

which balances the need to

ensure that safe and effective medicines

are provided on terms acceptable to

the health service against the need to

support a profitable pharmaceutical

industry in the UK.

2.10 The Pharmaceutical Price Regulation

Scheme (PPRS) is a voluntary agreement

between government

10

and the UK

pharmaceutical industry covering the

supply of most branded medicines. The

latest PPRS runs for five years from 1

January 2014. Under the terms of the

current PPRS, the pharmaceutical industry

has guaranteed that it will underwrite

any additional cost of supplying branded

medicines in the next two years. The

industry has also agreed to absorb an

element of any additional costs incurred

in the final three years of the PPRS.

2.11 The latest PPRS offers predictability (for

government and the pharmaceutical

industry) in the cost of branded

medicines for the next five years. As

a result of the increased certainty over

cost, the NHS hopes to move more

rapidly in adopting innovative medicines

and treatments where these will improve

patient outcomes. As PPRS is a UK wide

scheme further work is underway to

determine how its financial receipt for NI

is calculated.

NI reimbursement rates for dispensing

certain ‘generic’ drugs were based on

the Scottish Drug Tariff but this led to

legal challenge

2.12 The majority of items dispensed by

CPCs are generic drugs – that is,

drugs comparable to branded drugs in

dosage, strength, route of administration,

intended use, quality and performance

characteristics but created after expiry

of a patent. The Department has a

statutory obligation to compile and

9 The Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS) determines the prices drug manufacturers can charge for branded

drugs. Agreed prices follow negotiations between Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry and the Department

of Health (acting on behalf of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland). In November 2013, a new PPRS was

announced which took effect from January 2014 and will last for five years.

10 Although the agreement is made by the Department of Health, the arrangements apply to England, Scotland, Wales

and Northern Ireland. The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) negotiates on behalf of the entire UK

pharmaceutical industry.

20 Primary Care Prescribing

Part Two:

Community Pharmacy Contractors’ Reimbursement

Figure 5: Breakdown of the funding provided to CPCs in 2012-13

Element Definition Amount Paid in

2012-13

Reimbursement

costs

Contractors receive reimbursement for purchasing and

dispensing drugs on behalf of the HSC Board. The

actual price reimbursed to contractors for individual items

dispensed is set out in the Northern Ireland Drug Tariff.

The payments made are net of discounts to list prices, in

line with the process set out in the Drug Tariff.

(£409 million - £28.1 million discount)

Contractors achieve a level of ‘retained profit’ through

their purchase of medicines. Retained profit is the

difference between the price a contractor pays for a

drug and the price at which the contractor is reimbursed

(as set out in the Drug Tariff). The 2011-12 Margin

Survey demonstrated that contractors were generating an

estimated profit of £28 million through their procurement

activities. The estimated rate of the margin for branded

and generic medicines is similar to those identified in the

rest of the UK.

Propriety mitigation payments (amounting to £3.6 million

in 2012-13) were paid to contractors prior to completion

of the Margins Survey. Depending on the results of

the Margins Survey for 2012-13, propriety mitigation

payments may be subject to clawback.

The Department has commenced a Cost of Service

Investigation. The outcome of this investigation will be used

to inform future negotiations with community pharmacy

contractors and will inform the allowed level of retained

profit.

£380.9 million

Primary Care Prescribing 21

Global Sum Consists of two components:

(i) Annual Professional Practice Allowance

(APP Allowance)

Each year, a payment of £18,000 is paid for each

pharmacy in recognition that contractors contribute to the

provision of public health services.

(ii) Dispensing Fee

Contractors receive a fixed fee for dispensing an

approved drug or appliance to a public health service

patient. In 2012-13, the basic dispensing fees were:

Ordinary Fees: £1.03

Multiple Dispensing Fee: £0.49

Since 2009-10, a cap has been introduced on the total

Global Sum payable. In 2012-13, the number of ordinary

items dispensed was higher than anticipated. An amount

of £0.5 million was adjusted in 2013-14 to realign the

payments to the Global Sum, in line with the standard

operating process.

£51.4 million

£9.6 million.

£41.8 million

Additional

Non-Recurrent

Funding

The HSC Board also paid £7 million to contractors in

2012-13. This figure relates to a negotiated settlement

with CPCs following the outcome of a judicial review of

the Northern Ireland funding arrangements.

£7 million

Ancillary

Services and

Other Fees

Pharmacists can attract additional payments where they

provide supplementary services to patients. These services

may include availability of out of hours, the provision of

pharmacy advice to nursing and residential homes, or the

provision of training to non-qualified pharmacists. Remu-

neration rates for supplementary services are set out in the

Drug Tariff.

£19.8 million

TOTAL FUNDING

2012-13

£459.1 million

Source: HSC Board

22 Primary Care Prescribing

Part Two:

Community Pharmacy Contractors’ Reimbursement

publish a statement known as the

Northern Ireland Drug Tariff. The Tariff

sets out pricing models for generic drug

categories (Appendix 1). In July 1994,

the Department and the Pharmaceutical

Contractors Committee (PCC)

11

agreed

that it was appropriate to adopt the

Scottish Drug Tariff model in Northern

Ireland. Prices listed in the Scottish Drug

Tariff reflect prices set by the Department

of Health (England) since the UK

operates as one medicines market.

2.13 In 1999, following turbulence in the

pharmaceutical market, the Department

of Health (England) sought to rationalise

the prices of medicines to the NHS.

Research

12

published by the Department

of Health in England in 2003 estimated

that CPCs were typically able to make

30 per cent or more retained profit on

generic drugs. Research undertaken to

establish profit margins on ‘branded’

drugs in NI revealed similar trends to

other parts of the UK.

2.14 The research was not extended in

Northern Ireland to cover generic

drugs because local CPCs refused to

provide the required information. Later

research

13/14

has supported the view

that Northern Ireland CPCs, as part of

the UK-wide medicines market, enjoy

similar levels of profit to those generated

elsewhere in the UK. The on-going

Margins Survey estimates that CPCs

typically generated profit levels of 40

per cent in 2011-12.

2.15 On foot of the UK research, the

Department of Health (England)

launched a revised community pharmacy

contract in England and Wales in April

2005. In Scotland the contract was

phased in during 2006. An integral

part of that contract was the introduction

of a significant new category within

the UK Drug Tariff - Category M.

The Drug Tariff provides a funding

mechanism for pharmacists as well as

stimulating competition in the supply

chain. Financially, the Drug Tariff is set

to deliver a target level of retained profit

for CPCs and in Northern Ireland this is

set at £16.5m. Funding released from

the new Category M arrangements

are available to fund additional patient

focussed pharmaceutical services in the

community setting.

2.16 The revised contract was not introduced

in NI because pharmaceutical

representatives here contended that,

because the supporting information-

gathering exercise had not been

extended to NI, it could not be assured

that the new Category M would fairly

remunerate NI CPCs.

2.17 Despite the absence of agreement with

the local representatives, the Department

continued to apply the Scottish Drug

Tariff in Northern Ireland

15

. On

the basis that Northern Ireland was

recognised as part of a UK wide Drugs

Market and had been since 1998. In

effect, Category M was introduced in

11 The Pharmaceutical Contractors Committee (PCC) is the local representative body for community pharmacists providing

services under the National Health Service in Northern Ireland.

12 A pharmacy Cost of Service Inquiry (CoSI) report 2003.

13 NI - True Costs of NHS Pharmacy, The Tribal Report, 13 January 2011.

14 The on-going Margins Survey commenced in April 2011.

15 The drugs market operates on a UK-basis. All generic prices are set by the Department of Health (England) and included in

an English Drug Tariff. That Tariff covers England and Wales and is applied in NI. Scotland applies the English Drug Tariff

(after amendment to reflect variations in discount rates).

Primary Care Prescribing 23

Northern Ireland and CPCs in Northern

Ireland (as in other regions) saw their

reimbursement levels reduced.

2.18 Category M covers over 500 of the

most common generic medicines

dispensed. In NI, category M

covers about 55 per cent of all items

reimbursed and about 86 per cent of all

generic items reimbursed.

2.19 Given the concerns of CPCs, the

Department proposed that a proportion

of savings generated through Category

M would be paid where other services

were delivered (as in England, Scotland

and Wales). A subsequent disagreement

over whether payments should have

been made when these other services

were not provided, culminated in legal

challenge by CPCs. (Details of legal

proceedings against the Department are

set out in Appendix 2).

2.20 In 2010, a Judicial Review found in

favour of the CPCs and concluded

that the Department’s continued use of

the Scottish Drug Tariff did not meet

the statutory obligation to provide

fair and reasonable remuneration to

CPCs. The Department and HSC Board

subsequently took steps to put in place a

lawful Drug Tariff. A subsequent Judicial

Review in 2011 also found in favour

of CPCs but crucially, the revised Drug

Tariff was not deemed to be unlawful. In

December 2012, the Department and

HSC Board withdrew an appeal of the

Judicial Review decisions and a further

interim agreement was reached with

Community Pharmacy Northern Ireland

(CPNI).

The legal action has cost the

Department £550,000. CPCs received

compensation of some £6 million.

A further £40 million was made

available to CPCs over the seven

year period to 2011

2.21 The Judicial Review process has cost

the Department almost £550,000.

In addition, and outside the Judicial

Review process, the Department paid

£6 million to CPCs in 2006-07.

Following the outcome of the first Judicial

Review, the Department negotiated

an Interim Agreement with CPNI. As

part of that agreement, the Department

acknowledged the revised arrangements

resulted in lower reimbursement rates

and provided £40 million to CPCs

over the seven year period to 2010-11

inclusive of previous payments that had

already been made on account.

2.22 The Department has begun a NI Cost

of Service Investigation (CoSI)

16

and

anticipates that the data collection phase

will be completed by April 2015. The

outcome of the 2011-12 margins survey

became available in May 2014. A

2012-13 margins survey is currently

being undertaken. The Department

expects that the results of that will be

available by the end of 2014. The

outcomes of these investigations and

surveys will form the basis of further

negotiations with CPNI. The decision to

exclude multiples companies (as in the

rest of the UK), however, will limit the

extent of increased transparency.

16 The objective of the Cost of Service Investigation (CoSI) is to quantify the level of profit generated by CPCs.

24 Primary Care Prescribing

Part Two:

Community Pharmacy Contractors’ Reimbursement

2.23 While we accept that the Department

faced considerable opposition to

the implementation of Category M

in the Northern Ireland Drug Tariff,

in our view, many of the stumbling

blocks should have been foreseen

by the Department and overcome.

In particular, the Department should

have ensured that it was fully informed

about the likely economic impact

of introducing the revised tariff and

should have completed a Regulatory

Impact Assessment (RIA). Following the

outcome of the first Judicial Review,

it would have been prudent for the

Department to have completed an RIA

and investigation prior to enforcing

further change. The Department told us

that it completed, and consulted on an

economic analysis which supported

its view that no RIA was required.

We note however, that this was not

accepted as sufficient by the Court.

2.24 In addition to damaging relationships

with CPCs, the Judicial Review

process had a financial impact. While

no financial remedy was imposed by

the Courts, the Department told us that

the total cost incurred through both

Reviews amounted to £550,000.

2.25 We acknowledge that the Cost of

Services Inquiry and Margins Survey

will produce useful information on

the level of profit generated by

contractors. In our view however, the

decision to exclude multiples (as in

the rest of the UK) from the margins

survey, will limit the extent of increased

transparency. We recommend that the

Department reconsiders this decision.

Part Three:

Trends in General Practitioner (GP) Prescribing Practice

26 Primary Care Prescribing

Part Three:

Trends in General Practitioner (GP) Prescribing Practice

3.1 GPs use independent clinical judgement

to decide which drugs to prescribe. A

complex relationship of activities including

procurement, selection, prescribing,

dispensing, administration, monitoring

and review of medicines impact on both

clinical outcomes and cost. Research

17

has shown that GP prescribing behaviour

is influenced by many factors, which

operate at different levels in the health

and social care system. At the national

or international levels, clear evidence

on treatments and drugs presented in

authoritative journals is a significant

influence. The Department has noted

that it is therefore to be expected that an

equally complex array of activities are

required to ensure that optimal therapeutic

gains can be achieved from investment in

medicines while at the same time ensuring

value for money.

3.2 At the HSC level, influences include

local guidelines, newsletters, site visits

by HSC Board Medicines Management

Advisers, personalised contacts, and

recommendations from specialist or

consultants in the secondary health

care setting. At the practice level, the

professional experience of the GP, the

clinical needs of the patient, patient

demand, peer networks, and drug

company representatives may influence

prescribing. Decisions can, to an

extent, be influenced by the HSC Board

efficiency initiatives (see paragraph 4.2)

and by several other factors. A number of

examples are listed below.

• Legislation: The Health and Personal

Social Services (General Medical

Services Contracts) Regulations

(Northern Ireland) 2004 applies to

prescribing by GPs and requires that

a prescriber shall order any drugs,

medicines or appliances which are

needed for the treatment of any

patient.

• Guidance: A GP’s clinical decision

as to whether a drug is required

is complex. The General Medical

Council

18

(GMC) requires GPs “in

providing clinical care [to] provide

effective treatments based on best

available evidence”. It is policy in

NI to follow guidance provided

by The National Institute of Health

and Clinical Excellence (NICE)

guidance which is evidence based

and considered to be best practice.

GMC also advises GPs “To minimise

waste, improve services and promote

the effective use of resources, you

should take financial responsibility for

the delivery of your service at a level

appropriate to your role”.

• General Medical Services

contract

19

: The Quality and

Outcomes Framework (QOF) is part

of the General Medical Services

(GMS) contract for general practices

and was introduced on 1 April

2004. The QOF rewards practices

for the provision of ‘quality care’ and

helps to fund further improvements in

the delivery of clinical care. Practice

participation in QOF is voluntary

17 RAND Europe, Prescribing in primary care, Understanding what shapes GPs’ prescribing choices and how might these be

changed, 2006

18 General Medical Council Guidance: http://www.gmc-uk.org/index.asp

19 GMS Contract details are available at: http://www.nhsemployers.org/your-workforce/primary-care-contacts/general-

medical-services

but most practices take part. Given

that QOF provides incentives for

better disease management, it may

therefore have an influence on GPs’

prescribing behaviour.

• Access to information: GPs’

assessment of the clinical and cost

effectiveness of the drugs they

prescribe will be influenced by a

range of factors. The Department has

advised us that the Northern Ireland

formulary

20

is in place and is an

unbiased review of the medicines

and recommendation for first and

second line choices.

• Interaction with representatives

from the pharmaceutical industry:

In 2005, it was estimated that

the UK pharmaceutical industry

spends £1.65 billion a year on

drug promotion and marketing

21

.

It is likely, therefore, that marketing

activities can have an influence on

prescribing decisions.

• Secondary Care Prescribing:

Another influence on GPs’

prescribing is the secondary care

sector. In some cases, hospital

consultants specify a particular drug

for a patient leaving hospital and/

or an outpatient. While ultimately the

decision to prescribe rests with the

GP, it is likely that his decision will

be influenced by the clinical opinion

of the secondary care consultant.

The volume of prescribed drugs

has increased at a steady rate over

recent years but costs have fallen

substantially since 2010

3.3 In 2000, over 23 million items were

prescribed by GPs at a cost of just over

£245 million. Figure 6 shows that by

2010, the number of items prescribed

had increased to almost 36 million at

a cost of £440 million. Along with the

influences set out in paragraph 3.1, the

Department considers that the increase

also reflects the impact of a steadily

growing older population and the fact

that they consume more medicines.

3.4 The Pharmaceutical Clinical Effectiveness

(PCE) Programme

22

is a suite of

medicines management initiatives,

initiated by the Department in 2005 and

now implemented by the HSC Board.

Primary Care Prescribing 27

20 The NI formulary is available at: http://niformulary.hscni.net/Pages/default.aspx

21 House of Commons Health Committee, The Influence of the Pharmaceutical Industry 5 April 2005.

22 Pharmaceutical clinical effectiveness (PCE) is the outcome of the application of pharmaceutical skills directed to providing a

systematic approach to rational product selection and use, consistently applied across secondary and primary care, taking

account of clinical need, evidential product clinical performance, product presentation, safety characteristics and economic

factors. The process can be applied to medicines, wound care and medical and surgical disposable products. It employs

a multidisciplinary collaborative approach to reach consensus on the most appropriate clinical products and achieve the

ownership and behavioural change necessary to make the decisions operational. Effectively, in medicines terms, it is the

right medicine for the right patient at the right time and for the right cost. The PCE programme has been in operation since

2005 and represents the synergistic combination of a number of initiatives designed to optimise the implementation of the

product selection process through effective procurement, prescribing policy and guidelines and pharmaceutical service

improvements.

28 Primary Care Prescribing

Part Three:

Trends in General Practitioner (GP) Prescribing Practice

3.5 In the three year period, following the

introduction of PCE the rate of growth

in expenditure on drugs was reduced

to less than 5 per cent per annum (see

Figure 6) which, according to the

Department, resulted in £75 million in

savings having been made as part of

the targeted Comprehensive Spending

Review 2002-08 efficencies. The

Department also told us that between

2006-13, the cost of prescribing was

reduced in real terms by 18 per cent.

3.6 On 1 July 2010 responsibility for

managing the General Pharmaceutical

Services budget

23

was devolved from

the Department to the HSC Board. Since

2010, while the volume of prescriptions

continued to increase (by almost 5 per

cent to 2012), the cost of prescribing

these drugs has decreased by just over

7 per cent in the same period.

Spend (£ Million)

number of items (millons)

Spend Number of prescriptions

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

500

550

2012201120102009200820072006200520042003200220012000

15

20

25

30

35

40

Responsibility for the

General Pharmaceutical

Budget transferred to HSC

Board on 1 July 2010

Implementation of PCE

Figure 6: Percentage increases in the number and cost of items prescribed

Source: Business Services Organisation – Prescription Cost Analysis Reports

23

23 Responsibility for the entire Family Health Services Budget was devolved to the HSC Board on 1 July 2010. Family Health

Services expenditure includes General Medical Services, General Dental Services, General Pharmaceutical Services and

General Opthalmic Services.

Primary Care Prescribing 29

There have been a range of influences

which have helped to contain the cost

of primary care prescribing

3.7 GP prescribing decisions are tightly

regulated and monitored. Each year,

GP practices are subject to prescribing

reviews and repeat prescription audits.

The purpose of these reviews and audits

is to demonstrate that GPs have:

• implemented the National Institute for

Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

guidelines on prescribing and cost-

effectiveness;

• selected only medicines listed in the

NI Formulary; and

• implemented the Pharmaceutical

Clinical Effectiveness Programme

which sets key therapeutic objectives

that GP practices are encouraged

to implement which will deliver

improved quality, safety, effectiveness

and efficiency

3.8 Safe and cost-effective primary care

prescribing requires that:

• GPs have access to up-to-date

information about medicines;

• GP, hospital staff and pharmacy staff

co-ordinate prescribing activity;

• all new prescribers and prescribing

support staff receive sufficient, robust

training;

• generic medicines are used where

clinically appropriate; and

• medicine management advisers work

in tandem with practices.

3.9 GP Prescribing Incentive Schemes

played a part in influencing effective

prescribing. The schemes, which were

largely budgetary focused, were based

upon the principle that savings made

on the prescribing budget should be

shared between GP Practices and their

Local Commissioning Groups (LCGs).

The savings were retained by GP

Practices for reinvestment in services

designed to improve or enhance patient

care, without adding any additional

layer of bureaucracy. The savings

earmarked were also designed to assist

in reinvestment with health and social

care aimed at delivering improvements

to patient care. It is essential, especially

given the current financial constraints

within which the public sector finds

itself, that every opportunity to deliver

efficiencies is pursued.

30 Primary Care Prescribing

Part Three:

Trends in General Practitioner (GP) Prescribing Practice

HSC Board Medicines Management

Advisors have been instrumental in

ensuring prescribing efficiencies are

generated

3.10 Containing the cost of prescribing

by GPs is primarily managed by the

HSC Board’s Medicines Management

Advisers (MMAs) who seek to influence

the prescribing behaviour of GPs. As

qualified pharmacists, MMAs perform

two main functions:

• each MMA monitors the prescribing

patterns of an allocated number of

GP practices (approximately 25 for

a full-time MMA) with a focus on

safety, effectiveness and efficiency.

By identifying high value expenditure

and variations in prescribing

patterns, MMAs are well placed

to highlight areas where financial

savings could be generated without

impacting on the quality and safety

of care; and

• each MMA is responsible for

reviewing prescribing patterns

within given therapeutic areas

(such as obesity or asthma). The

MMA is set a specific effectiveness

target for this area and influences

prescribing practice by providing

comprehensive, up to date advice to

GPs on the most effective treatments.

3.11 In part, the success of MMAs is reflected

in achievement against annual GP

prescribing efficiency-saving targets

which have been in place since

2010-11

24

(see Paragraph 4.2). By

encouraging GPs to prescribe more cost-

effectively by, for example, increasing

the level of generic prescribing and

identifying areas where cheaper

alternatives (proven to have the same

outcomes) can be used, MMAs have

played an important role in helping

to slow the year-on-year increase in

the number of items dispensed and to

reduce costs.

3.12 The ratio of MMAs per head of

population has been used in Scotland

to demonstrate that prescribing

performance can be enhanced by

increasing MMA capacity. Compared to

Scotland

25

, the ratio is lower here with 1

whole time equivalent (WTE) MMA per

130,000 of the population compared

to between 3.5 and 6 WTE prescribing

support staff (similar to the role of MMAs

in NI) per 100,000 of the population in

Scotland.

24 Until July 2010, the Department had responsibility for the General Pharmaceutical Service budget. It set the efficiency target

of £40 million for that year. Responsibility was then devolved to the HSC Board.

25 Audit Scotland Report: Prescribing in General Practice in Scotland 2013.

3.13 While the relative impact of various

prescribing support activities is difficult

to assess, in our view, MMAs play

a key role in controlling prescribing

costs by coordinating these activities.

We recommend that the HSC Board

should use available benchmarking

data to inform their consideration of

whether MMA staffing levels in NI

are appropriate. The Department has

informed us that it recognises the role

of MMAs and will consider available

evidence from NI and elsewhere to

inform consideration of appropriate

and affordable staffing levels.

Primary Care Prescribing 31

British National Formulary (BNF)

3.14 The British National Formulary (BNF) is

a publication which contains information

and advice on prescribing, dispensing

and administering medicines. It is used

by GPs and pharmacists to confirm

drug dosages, indications, interactions

and side effects. Medicines are classed

in accordance with their therapeutic

actions and are categorised against

one of 15 BNF chapters. Some drugs,

such as aspirin, appear in a number of

BNF chapters since they can be used to

treat several conditions. Basic net prices

are given in the BNF to provide an

indication of the relative cost of different

drugs.

3.15 The NI administrative prescribing

database, hosted by The HSC Sector

Business Services Organisation (BSO),

classifies medicines in accordance

with the BNF format in order to report

prescribing/dispensing activity by

therapeutic areas. BSO include

one additional section allocating

unclassified

26

medicines. Typically

over 60 per cent of the total cost

of prescribing falls to one of four

therapeutic areas (see Figure 7).

26 Unclassified are dispensed items for which there is no corresponding code in the NI Code book issued by BSO.

Figure 7: 2013 Expenditure in top four BNF Chapters

BNF Chapter Conditions

Commonly Treated

2013

Expenditure

Percentage of

overall prescribing

expenditure in

2013

BNF 4 –

Central Nervous System

Depression, dementia,

alzheimers disease, multiple

sclerosis, pain

£113 million 28 per cent

BNF 2 –

Cardiovascular System

Angina, heart attacks £48 million 12 per cent

BNF 3 –

Respiratory System

Asthma, emphyzema, chronic

obstructive pulmonary disorder,

acute respiratory distress,

sinusitis, tonsillitis, laryngitis

£48 million 12 per cent

BNF 6 –

Endocrine System

Diabetes, thyroid problems,

osteoporosis

£45 million 11 per cent

Source: Business Service Organisation

32 Primary Care Prescribing

Part Three:

Trends in General Practitioner (GP) Prescribing Practice

3.16 Around 20 per cent falls to a further five

therapeutic areas, with four per cent of

all prescribing expenditure allocated to

‘unclassified’ (see Figure 8).

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

Total for remaining

Unclassified

Skin

Obstetrics,

Gynaecology and

Urinary-Tract disorders

Gastro-Intestinal

system

Nutrition and Blood

Endocrine system

Respiratory system

Cardiovascular

system

Central Nervous

system

BNF Chapters

Spend (£ Million)

Figure 8: Analysis of 2013 Expenditure by BNF Chapter

Source: HSC Board

Primary Care Prescribing 33

The use of an ‘unclassified’ category

prevents comprehensive analysis of

prescribing patterns

3.17 Where a GP prescribes an unusual

item or a liquid form of a routinely

dispensed tablet, the items is allocated

to the ‘unclassified’ category. In 2013,

250,000 prescription items costing £15

million were charged to the unclassified

code. Figure 9 shows that the level of

unclassified expenditure has more than

doubled in the 10 year period to 2013.

Figure 9: Spend allocated to the unclassified category in NI over the period 2004 to 2013

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

2013201220112010200920082007200620052004

Spend (£ Million)

Source: HSC Board

34 Primary Care Prescribing

Part Three:

Trends in General Practitioner (GP) Prescribing Practice

3.18 It is, however, the view of the HSC

Board that the inclusion of an unclassified

category allows greater transparency

and allows the quantification and

interrogation of the use of these products.

In Scotland, unclassified items (referred

to as dummies in Scotland) represented

less than two per cent of the prescribing

costs. England and Wales do not use

an unclassified category. All prescribed

items are allocated to a BNF chapter/

therapeutic area.

3.19 We examined the top 100 most

expensive items prescribed and

allocated to ‘unclassified’ in December

2013. In our sample we identified that:

• Just over half of all items selected

(costing £46,000) were liquid forms

of routinely dispensed medicines;

• Pharmacists had been reimbursed

between £622 and £1,230 for

dispensing individual liquid (rather

than tablet) doses of omeprazole.

Tablet form omeprazole costs

approximately £2.27;

• In one case, a pharmacist was

reimbursed £220 for dispensing a

‘special

27

’ suspension. We noted that

this product was available on the

market at a cost of £23.43; and

• An application for reimbursement

relating to a ‘special’ item costing

just over £400 was turned down

by the HSC Board. The HSC Board

advised the pharmacist to dispense