Requirements Analysis and Management for

Benefiting Openness

Johan Lin

˚

aker

Department of Computer Science

Lund University, Lund, Sweden

Krzysztof Wnuk

Department of Software Engineering

Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona, Sweden

Abstract—Requirements Engineering has recently been greatly

influenced by the way how firms use Open Source Software (OSS)

and Software Ecosystems (SECOs) as a part of their product

development and business models. This is further emphasized by

the paradigm of Open Innovation, which highlights how firms

should strive to use both internal and external resources to

advance their internal innovation and technology capabilities.

The evolution from market-driven requirements engineering and

management processes, has reshaped the understanding of what a

requirement is, and how it is documented and used. In this work,

we suggest a model for analyzing and managing requirements

that is designed in the context of OSS and SECOs, including the

advances and challenges that it brings. The model clarifies how

the main stages of requirements engineering and management

processes can be adjusted to benefit from the openness that the

new context offers. We believe that the model is a first step

towards the inevitable adaptation of requirements engineering to

an open and informal arena, where processes and collaboration

are decentralized, transparency and governance are the key

success factors.

Keywords: Open Innovation, Open Source Software, Software

Ecosystem, Requirements Engineering, Requirements Manage-

ment, Software product management

I. INTRODUCTION

Software-intensive firms continuously have to face new

challenges in order to sustain their competitive advantage.

Known factors that they have learned to identify, and to a

large degree control over the years include frequent technology

changes [3] and shifting market needs [23]. During the past

decade, the advent of various forms of openness, such as

Software Ecosystems (SECOs) [12] and Open Source Software

(OSS) has become pivotal parts of many firms’ product devel-

opment and business models. This has pushed them into a new

unknown context where they need to “learn how to play poker

as well as chess” [5] by searching for, experimenting with,

and ultimately using externally generated innovation. This new

open context may be further explained by the Open Innovation

(OI) model, which highlights how firms should strive to use

both internal and external resources to advance their internal

innovation and technology capabilities [22].

Requirements Engineering (RE) has primarly focused on

internal (from within the firm) stakeholder interaction in

regards to activities such as analysis, research and develop-

ment [28]. Market-Driven Requirements Engineering [23] and

crowdsourcing [11] brought more focus on external stake-

holders. OI has not only blurred the boundaries between

internal and external contexts, but also greatly extended the

scope of requirements activities to entire ecosystems or open

communities. Moreover, OI brought the support for both the

adoption of externally acquired innovation and the active

commercialization of internally generated innovations that are

not aligned with the current business model (e.g. via licensing

or sale) [5]. As a result, and due to strong relationship between

requirements engineering and value creation [3], requirements

engineering for OI need to be reshaped to better “sustain

innovation” [13]. As pointed out by Rohrbeck et al. [24] value

should no longer only be created for customers but must also

be captured for partners and suppliers in increasingly more

complex and collaborating ecosystems.

In our previous work, we investigated OI in a large organiza-

tion that recently transitioned to an OI model by abandoning

the development of a purely proprietary code base for their

software product and making use of an OSS project (referred

as a ”platform”) as a source of innovation (in both knowledge

and technology) [28]. The platform is not only the main

component of the firm’s product, but is also available to, or

used by any other player within the SECO. The focus on

previous investigation was on identification of requirements

management [10] and decision making challenges associated

with the adoption of OI.

In this vision paper, we propose a model for managing

requirements that helps to benefit from openness and responds

to previously outlined challenges. In particular, we believe

that the model contributes in requirements elicitation, analysis,

release planning and commercialization of internally generated

requirements that are not aligned with the current products or

business models.

This paper is structured as follows. Section II brings

background and related work while Section III outlines and

explains our model. We conclude the paper in Section IV and

discuss future work direction.

II. BACKGROUND

Here we present how OI connects to Software Engineering,

and how RE differentiates in an open versus a closed context.

A. Software Engineering in Open Innovation

The OI model is commonly described with the use of a

funnel [5], see Fig. 1. The funnel itself represents the software

arXiv:2208.02629v1 [cs.SE] 31 Jul 2022

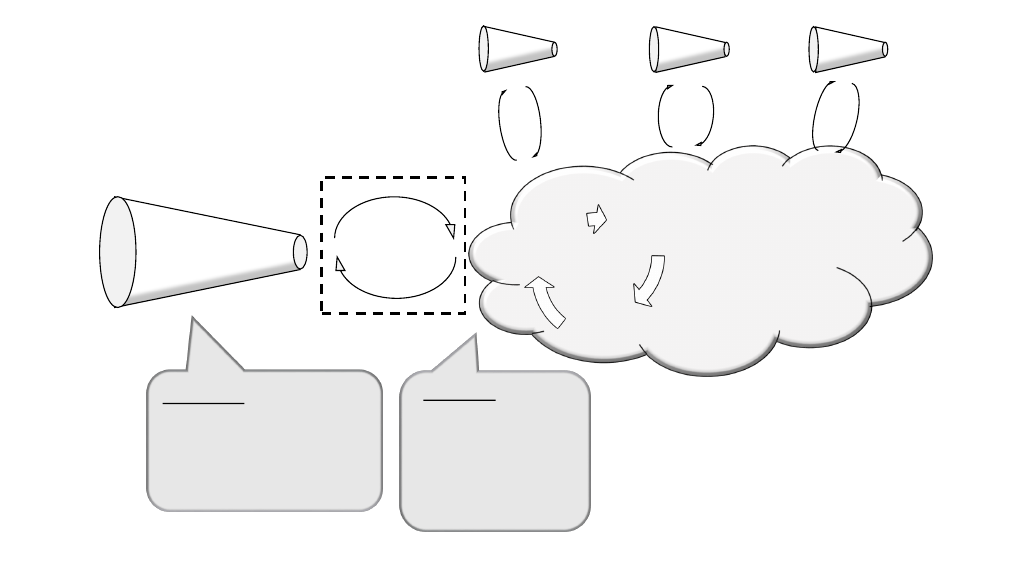

Fig. 1. The OI model illustrated with interactions between the firm (funnel)

and its external collaborations. Adopted from Chesbrough [5].

development process. This may in turn be illustrated either as

an iterative process, or just as one single development cycle

(e.g. from RE, design, implementation, test, to release). The

funnel is full of holes representing openings between the firm’s

development process and the open environment, in our case,

an OSS ecosystem. The arrows going in and out represent

transactions and exchange of knowledge between the two, such

as feature requests or bug reports, design proposals or feature

road maps, feature implementations or bug fixes, test cases,

complete sets of code as in plugins, components, platforms or

even products. From the RE perspective this includes activities

such as elicitation, prioritization and release planning, which

are performed interactively between the internal and the open

environment.

The knowledge exchange illustrated in Figure 1 may be bi-

directional, i.e. it can go into the development process from

the open environment (outside-in), or from the development

process out to the open environment (inside-out). On the left-

hand side the arrows represent the intent and business model,

which encompasses and motivates the development process.

On the right-hand side the arrows represent the output from

the development process, with some degree of innovation. This

output may be a new or improved product or service from

which the company may capture or create value with the help

of their business model. Also on the right-hand side are the

bulls-eye marks, which represents the current but also new

alternative markets to which the firm’s business model could

deliver the product or service produced from their development

process.

B. Requirements Engineering in Open Innovation

Fig. 2 presents RE in the context of OI. An example

software-intensive firm is represented by a funnel, connecting

to the OI model. The open environment, or a OSS ecosystem,

with which the firm interacts, is represented by the cloud.

Other actors, which for example may include individuals,

NPOs and other firms are also represented by a funnel each.

We further need to differentiate between an internal and

external RE process. With internal, we refer to the process

connected to a firm’s internal software product development.

The external concerns the one used in an OSS ecosystem with

which the firm, and all other actors, interact with.

Looking at OSS ecosystems, requirements practices are

often informal and overlapping [25]. Requirements are com-

monly asserted through transparent discussions and sugges-

tions by the OSS project’s developers and users, often together

with prototypes or proof-of-concepts [2], [8]. Assertion may

also be done post-hoc, simultaneously as the requirement

realization [7], [8]. These assertions are specified and managed

in what Scacchi refers to as informalisms [25], e.g. reports in

an issue tracker, messages in a mailing list, or commits in a

version control system. Through social interaction facilitated

by the infrastructure persisting the informalisms, requirements

are further enriched and validated [26], [7], [8]. Prioritization

is commonly conducted by ecosystem maintainers overseeing

the project management, though care is often taken to the

opinions of other developers and users (e.g. through votes and

comments [16]). Ernst & Murphy refers to this lightweight

and evolutionary process of requirements refinement as Just-

In-Time (JIT) requirements (illustrated by the circular arrows

inside the OSS ecosystem in Fig. 2), compared to the more tra-

ditional upfront requirements characterized by heavy processes

and tool support [7]. Further, Alspaugh & Scacchi contrasts

how OSS RE steps away from what they refer to as Classical

Requirements, characterized as having a central repository,

with requirements defined in the problem space, describing

the product of need, along with processes for examining the

requirements for completeness and consistency [2]. For better

consistency, we choose to re-label JIT and OSS RE as Open

RE, and that described as traditional upfront, and classical

requirements as Closed RE.

Release-planning in OSS ecosystems is often employed

using either a feature-based and time-based strategy [21]. The

feature-based performs a release when a set goals have been

fulfilled, e.g. a certain set of features has been implemented.

The time-based performs releases according to a preset sched-

ule. Hybrid versions has also used [29]. Earlier work has

reported a favor towards the time-based strategy [20], [29].

With fixed release dates and intervals, firms can better adapt

their internal plans so that additional patchwork and differen-

tiating features may be added in time for product shipment

to market [20], [21]. Other issues associated with time-based

release strategy include: rushed implementations, workload

accumulation, outdated software and delayed releases [20].

Open RE, compared to Closed RE, can be seen as being

informal to different degrees, e.g., to what level requirements

are analyzed and managed [7]. Requirements are often de-

centralized and distributed over multiple sources, often with

a limited tracing. Influence and participation in the work and

decision-making are also distributed. Discussions and steering

documents are all public and transparent for anyone to see, or

participate. Collaboration and negotiation about requirements

• Prioritization

• Release planning

• Scoping

• Management

Realization

Open RE:

• Informal

• Transparent

• Decentralized

• Distributed

• Collaborative

Closed RE:

• (Semi)Formal

• Need-to-know basis

• Centralized

• Collaborative by choice

Open Source Software Ecosystem

RE process

Software-intensive firm

Other Software-intensive firm

Specification

Validation

Elicitation

NPOs

Individuals

Firm’s RE process

RAMBO

Fig. 2. The requirements engineering context influenced by the OI paradigm.

are key, as consensus often is needed to make certain deci-

sions [1]. These distinctions between Open and Closed RE

visualize a process and knowledge gap that commonly exist

between firms and OSS ecosystems on the context of OI [22],

[28]. This gap need to be addressed to the firms can increase

their benefits from ecosystem participation (both monetary

and non-monetary), ecosystems can get more active players

and enriched discussions and influence and customer can

receive better products with shorter time to market and greater

degree of innovation. This is what we aim to address with the

construction of the Requirements Analysis and Management

for Benefiting Openness (RAMBO) model. The model focuses

on the interaction and overlap between the internal RE process

of the focal firm, with that of its connected OSS ecosystem,

to better manage the challenges implied by OI.

III. REQUIREMENTS ANALYSIS AND MANAGEMENT FOR

BENEFITING OPENNESS (RAMBO)

Figure 3 outlines the RAMBO model. The model is divided

into five phases outlined in the subsections that follow: 1)

requirements elicitation, 2) requirements screening and pre-

analysis, 3) Open Innovation potential analysis, 4) spin off

analysis and 5) realization and contribution analysis. In the

context of this work we follow the definition of Requirements

Management (RM) provided by Hood et al. as “the set

of procedures that support the development of requirements

including planning, traceability, impact analysis, change man-

agement and so on... and the sum of the interfaces between

requirements development and all other systems engineering

disciplines such as configuration management and project

management.” [10]. We also recognize the role of requirements

management in supporting managing requirements between

products and projects.

A. Step 1: Elicitation

Requirements Elicitation in OI (marked with 1 in Figure 3)

differs greatly from previously known and published contexts.

During requirements elicitation, a firm that operates in OI

needs to quickly and properly identify which of the sources

of requirements to use, and for what purpose. OI still contains

the ”classical“ internal and MDRE requirements sources, but

is extended by the open sources of requirements.

The internal requirements sources (typical for bespoke RE)

are characterized by a small and well known set of customers

or stakeholders whose wishes or constraints are important and

taken into consideration. Apart from that, any firm that sells a

product on an open market needs to elicit requirements from

the MDRE sources through a balance of market-push and

technology-pull [23]. Wishes from customers, both known and

unknown, are elicited through more traditional methods (e.g.,

interviews) complemented with approaches such as market

analysis. New functionality and innovative requirements are

added internally as R&D progresses and the product evolves.

Regarding open sources, such as an OSS ecosystem, re-

quirements are both market- and technology-driven as in

MDRE. A difference is that in an OSS ecosystem, it usually is

the end-users who are actively suggesting new requirements

as well as driving the innovation forward by co-developing

the products. However, active elicitation may still be needed,

but through new approaches such as participation in discus-

Internal

sources

MDRE

sources

Open

sources

1

Requirements

Elicitation

IFAREQUIREMENT

ORSHOULDITBE

AREQUIREMENT

Pre‐analysis

Screening

2

YES

YES

Bug

WUP

PW

Contribute? Explain

DOESITFITTOTHE

PRODUCTSTRATEGY

ORBUSINESS

MODEL?

NO

NO

OI

Analysis

3

SEPARATEDREQUIREMENTSFLOW

DOIT?

SHAREIT?

DROP IT?

MAINREQUIREMENTSFLOW

SPINOFF

ANALYSIS

4

Architecture

Impact

Analysis

Implementation

Proposals

Contribution

Options

REALIZATION

ANDCONTRIBUTION

ANALYSIS

5

SELLIT?

Fig. 3. The Requirements Analysis and Management for Benefiting Openness (RAMBO) model.

sions facilitated by the ecosystem infrastructure (e.g., mailing-

lists, issue-trackers and IRC-channels) and at off-line events

(e.g., user-conferences and hackathons). Crowdsourcing as a

requirements elicitation technique is also highly recommended

here as it increases the quality and comprehensiveness and

even the economic feasibility of requirements elicitation [11].

Moreover, requirements elicited from the crowd rather accu-

rately represent the needs and pains of that crowd, allowing to

skip a large part of requirements validation process and pro-

viding quick feedback. Stakeholder discovery is also greatly

supported by crowdsourcing that provides opportunities to

create user personality clusters [9] and filter their opinions

about the products and requested requirements. This greatly

supports user feedback analysis and helps in defining new

requirements. Finally, the identification, analysis and priori-

tization of present stakeholders is key to find those relevant,

and can bring valuable requirements that increase profitability.

Embracing and supporting creativity is important as this

stage as new ideas that both fit into the current product

portfolio and are way beyond it are much appreciated. The

illumination and verification parts of creativity workshops can

greatly support requirements discovery and idea generation

that can be further detailed in OI contexts [19]. Automated

support for creativity is highly desirable here as the number

of unfamiliar connections between familiar possibilities of re-

quirements is high and can overload requirements analysts [4].

As with MDRE, the number of requirements grows fast

in an OSS ecosystem, creating potential problems in regard

to managing quality aspects such as dependencies and com-

plexity. Another aspect is that prioritization and throughput of

requirements suffers due to the large repositories. Specific for

the OI context however, is that the requirements are spread

out in several decentralized repositories (informalisms [25]),

often very unstructured and expressed both through a variety

of implementations and natural language descriptions.

B. Step 2: Pre-Screening and Analysis

After all relevant sources (Open, MDRE and internal if

relevant) are identified and prioritized, the requirements orig-

inating from these sources need to be screened. Requirements

screening in OI is significantly challenging due to the follow-

ing reasons: 1) they are spread out in several decentralized

repositories, 2) they are unstructured and 3) everyone has

access to them and can already be working on their implemen-

tation, 4) consideration often has to be taken to others’ opinion

(e.g., in a meritocracy), and 5) many of the requirements

are actually bug fixed, Wrong Usage of a Product (WUP)

(user of customer misunderstood how to use the product) or

Problems that have Workarounds (PW) and can be solved

without additional implementations.

Therefore, the main part of the screening process is the

decision if the analyzed piece of information is a requirements

or should be a requirement. Here, we would like to stress that

RE in OI should adopt a broad definition of what a requirement

is, which also includes needs for stakeholders that are not

relevant for a given product but could be relevant for a spin-off

product. This implies that the product boundaries or constraints

are greatly removed and make a vast majority of requirements

potentially interesting or relevant. Therefore, RE in OI requires

a lightweight and efficient method for quickly investigating the

relevance and novelty of potential requirements, along with

the potential cost and contribution strategy in consideration.

Previous work by Maalej and Nabil [18] provides promising

results for classifying app reviews as bug reports, feature

requests, user experiences and ratings. Laurent et al. [15]

proposed a method for automated requirements triage that

cluster incoming stakeholder requests into hierarchical feature

sets. We argue that their work should be extended by adding

OI-specific concerns, e.g. contribution potential and realization

options.

The challenge here remains in analyzing incoming re-

quirements with openness in mind, e.g. taking the broader

perspective than suggested by Davis effort, dependency and

important analysis, multiple release planning [6] or impacted

business goals suggested by Laurent et al. [15]. In this

broader perspective, a requirements analysis should calcu-

late the probability of completion if someone else from the

ecosystem contributes in co-development or analyze optimistic

or pessimistic scenarios with or without other contributions

within the same OSS ecosystem.

C. Step 3: OI Analysis

When relevant requirements are identified and screened,

their OI potential need to be analyzed. This third step of the

RAMBO model represents a significant difference between

MDRE and RE in OI. In MDRE, requirements are analyzed

through the lens of the current product portfolio, along with

the stakeholders, their needs and future plans. Incremental

innovation has higher changes to be selected as radical ideas or

ideas not associated with significant stakeholders are consid-

ered risky or unprofitable. This was considered as a challenge

in our previous investigations and resulted in many promising

ideas been rejected [28]. RE in OI needs to take a broader

perspective and consider these “not fitting” requirements as po-

tential spin-off ideas. This addressed the well-known ”PARC

Problem” experienced by Xerox [5]; the inability to assess

and capture value for (technology) innovations that were not

directly related to Xerox products. As quite often not all

requirements can be implemented in the next release due

to low priorities and lack of resources, the potential waste

of unimplemented ideas can be shared with other ecosystem

players. Therefore, step 3 of the model investigates if the

potential requirements fit into the current product portfolio or

future plans, or not. Even if some requirements do not fit into

the current strategies, they should not stay “locked” internally

in the requirements database or be down-prioritized by more

urgent requirements, but made open and shared with other

players who may find them more relevant for their offerings.

D. Step 4: Spin Off Analysis

Requirements that are considered as not the best fit for

the current product portfolio, can and should be shared with

other ecosystem players. Moreover, potential spin-offs should

be discussed and executed to benefit from potential novelty

and innovation included in those requirements. This step often

involves making alliances with other ecosystem players or

spinning-off start-up companies that can develop and monetize

these ideas. The important factor in this step is also to make

an effort on keeping the key personnel away from leaving the

firm together with the new ideas. This step corresponds to the

inside-out part of the knowledge exchange in the OI model,

see Figure 1. Open requirements and increased transparency

in release plans are important at this stage. For example,

assuming that two ecosystem players are working jointly on a

feature that is going to provide substantial benefits for the

customers, there should to be a discussion and agreement

about release plans synchronization so that both players can

benefit from the feature. These release plans should also be

synchronized with previously agreed contribution strategy for

the feature so that maintenance costs can be directly minimized

via commoditization. Finally, ideas may also be dropped if

considered not interesting enough or economically viable.

E. Step 5: Realization and Contribution Analysis

Requirements considered as a good match for the current

product strategy need to be analyzed from the realization

and contribution perspectives. First, the Architecture Impact

Analysis (AIA) need to be performed to understand the impact

of new requirements on the current architecture and potential

changes that need to be made during the implementation. The

involvement of software architect as a technical counterpart of

software product manager is important at this stage to ensure

the alignment between product requirements and architecture

and create a stepwise architectural evolution that fits with the

product roadmaps [17].

Second, the Implementation Possibilities (IP) (adaption of

OSS solution, differentiation based on commodity offered

by OSS, or fully own implementation) are analyzed and

considered. Each of the three options need to be analyzed

from the potential value and long-term cost perspective. The

risk associated with fully own implementation is a signifi-

cant change to the common code base and several patches.

Moreover, the OSS ecosystem may in the near future come

up with a solution to exactly the same requirement that may

be equally as good, or even better than the firm’s own. Finally,

Contribution Options (CO) need to be considered, and the

scope and time line of contributions need to be set. Both

realization and analysis of contribution options require the

following two elements: 1) a good understanding of the value

from both customer and internal business perspectives [14]

and 2) an understanding of the commoditization process for

a given product or market that will help in estimating if and

when a given implementation should be contributed to the

open community. [27].

IV. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE WORK

In this paper, we present our vision of the Requirements

Analysis and Management Model for Benefiting Openness that

we designed with the specific challenges in mind that Open

Innovation brings to Requirements Engineering. Our model

recognizes the challenging aspects of stakeholder and re-

quirements elicitation, triage, analysis and implementation that

Open Innovation brings. We have summarized the RAMBO

model in five steps and explain how each of the steps differ

from commonly accepted requirements engineering practice.

Our vision need significant further work that we plan in the

near future. Firstly, we plan to study each of the associated

requirements phases in more detail and bring more evidence

of the lack of support for these activities. We plan to use

our industry network to search for empirical evidence if

the activities outlined in the RAMBO model are currently

performed and in what way or maybe not performed. Secondly,

we plan to select one large company that operated in OI and

study its requirements process to create process improvement

action plan that will encourage them to adapt the parts of the

RAMBO model that are currently not present. Finally, we plan

to create a governance model for RE in OI that will contain all

relevant activities and decision points that a software-intensive

firm should consider to better utilize the benefits that openness

offers.

REFERENCES

[1] P

¨

ar J

˚

Agerfalk and Brian Fitzgerald. Outsourcing to an unknown

workforce: Exploring opensurcing as a global sourcing strategy. MIS

quarterly, pages 385–409, 2008.

[2] Thomas A. Alspaugh and Walt Scacchi. Ongoing software development

without classical requirements. In Requirements Engineering Conference

(RE), 2013 21st IEEE International, pages 165–174. IEEE, 2013.

[3] Ayb

¨

uke Aurum and Claes Wohlin. Requirements Engineering: Foun-

dation for Software Quality: 13th International Working Conference,

REFSQ 2007, Trondheim, Norway, June 11-12, 2007. Proceedings, chap-

ter A Value-Based Approach in Requirements Engineering: Explaining

Some of the Fundamental Concepts, pages 109–115. Springer Berlin

Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007.

[4] T. Bhowmik, N. Niu, A. Mahmoud, and J. Savolainen. Automated

support for combinational creativity in requirements engineering. In

2014 IEEE 22nd International Requirements Engineering Conference

(RE), pages 243–252, Aug 2014.

[5] H.W. Chesbrough. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating

and Profiting from Technology. Harvard Business School Press, 2006.

[6] Alan M. Davis. The art of requirements triage. Computer, 36(3):42–49,

March 2003.

[7] N.A. Ernst and G.C. Murphy. Case studies in just-in-time requirements

analysis. In 2012 IEEE Second International Workshop on Empirical

Requirements Engineering (EmpiRE), pages 25–32, September 2012.

[8] Daniel M. German. GNOME, a case of open source global software de-

velopment. In International Workshop on Global Software Development,

pages 39–43, 2003.

[9] Eduard C. Groen, Joerg Doerr, and Sebastian Adam. Towards Crowd-

Based Requirements Engineering A Research Preview, pages 247–253.

Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2015.

[10] C. Hood, S. Wiedemann, S. Fichtinger, and U. Pautz. Requirements

Management: The Interface Between Requirements Development and All

Other Systems Engineering Processes. SpringerLink: Springer e-Books.

Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2007.

[11] Mahmoud Hosseini, Keith T Phalp, Jacqui Taylor, and Raian Ali.

Towards crowdsourcing for requirements engineering. 2014.

[12] S. Jansen, M.A. Cusumano, and S. Brinkkemper. Software Ecosystems:

Analyzing and Managing Business Networks in the Software Industry.

Edward Elgar Publishing, Incorporated, 2013.

[13] M. Kauppinen, J. Savolainen, and T. Mannisto. Requirements engineer-

ing as a driver for innovations. In Requirements Engineering Conference,

2007. RE ’07. 15th IEEE International, pages 15–20, Oct 2007.

[14] Mahvish Khurum, Tony Gorschek, and Magnus Wilson. The software

value map - an exhaustive collection of value aspects for the develop-

ment of software intensive products. Journal of Software: Evolution and

Process, 25(7):711–741, 2013.

[15] P. Laurent, J. Cleland-Huang, and C. Duan. Towards automated require-

ments triage. In 15th IEEE International Requirements Engineering

Conference (RE 2007), pages 131–140, Oct 2007.

[16] Paula Laurent and Jane Cleland-Huang. Lessons Learned from Open

Source Projects for Facilitating Online Requirements Processes. In

Martin Glinz and Patrick Heymans, editors, Requirements Engineering:

Foundation for Software Quality, number 5512 in Lecture Notes in

Computer Science, pages 240–255. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2009.

[17] Garm Lucassen, Fabiano Dalpiaz, Jan Martijn van der Werf, and Sjaak

Brinkkemper. Bridging the twin peaks: The case of the software

industry. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Workshop on Twin

Peaks of Requirements and Architecture, TwinPeaks ’15, pages 24–28,

Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015. IEEE Press.

[18] W. Maalej and H. Nabil. Bug report, feature request, or simply praise? on

automatically classifying app reviews. In 2015 IEEE 23rd International

Requirements Engineering Conference (RE), pages 116–125, Aug 2015.

[19] N. Maiden and S. Robertson. Integrating creativity into requirements

processes: experiences with an air traffic management system. In 13th

IEEE International Conference on Requirements Engineering (RE’05),

pages 105–114, Aug 2005.

[20] M. Michlmayr, B. Fitzgerald, and K.-J. Stol. Why and How Should

Open Source Projects Adopt Time-Based Releases? IEEE Software,

32(2):55–63, March 2015.

[21] Martin Michlmayr, Francis Hunt, and David Probert. Release Man-

agement in Free Software Projects: Practices and Problems. In Joseph

Feller, Brian Fitzgerald, Walt Scacchi, and Alberto Sillitti, editors, Open

Source Development, Adoption and Innovation, number 234 in IFIP —

The International Federation for Information Processing, pages 295–300.

Springer US, 2007.

[22] Hussan Munir, Krzysztof Wnuk, and Per Runeson. Open innovation in

software engineering: a systematic mapping study. Empirical Software

Engineering, pages 1–40, 2015.

[23] Bj

¨

orn Regnell and Sjaak Brinkkemper. Engineering and Managing Soft-

ware Requirements, chapter Market-Driven Requirements Engineering

for Software Products, pages 287–308. Springer Berlin Heidelberg,

Berlin, Heidelberg, 2005.

[24] Ren

˜

A© Rohrbeck and Jan Oliver Schwarz. The value contribution of

strategic foresight: Insights from an empirical study of large european

companies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 80(8):1593

– 1606, 2013.

[25] Walt Scacchi. Understanding Requirements for Open Source Soft-

ware. In Kalle Lyytinen, Pericles Loucopoulos, John Mylopoulos,

and Bill Robinson, editors, Design Requirements Engineering: A Ten-

Year Perspective, number 14 in Lecture Notes in Business Information

Processing, pages 467–494. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2009.

[26] Richard Torkar, Pau Minoves, and Janina Garrig

´

os. Adopting

free/libre/open source software practices, techniques and methods for

industrial use. Journal of the Association for Information Systems,

12(1):88–122, 2011.

[27] Frank Van der Linden, Bj

¨

orn Lundell, and Pentti Marttiin. Commodifi-

cation of industrial software: A case for open source. IEEE Software,

26(4):77–83, 2009.

[28] K. Wnuk, D. Pfahl, D. Callele, and E. A. Karlsson. How can open source

software development help requirements management gain the potential

of open innovation: An exploratory study. In Empirical Software

Engineering and Measurement (ESEM), 2012 ACM-IEEE International

Symposium on, pages 271–279, Sept 2012.

[29] H.K. Wright and D.E. Perry. Subversion 1.5: A case study in open

source release mismanagement. In ICSE Workshop on Emerging Trends

in Free/Libre/Open Source Software Research and Development, 2009.

FLOSS ’09, pages 13–18, May 2009.