DISCLAIMER This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was

prepared by NORC at the University of Chicago. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the

views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government.

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE

OBIRODH – ROAD TO TOLERANCE

YOUTH LEADERSHIP TRAINING

PROGRAM IN BANGLADESHI

UNIVERSITIES

FINAL REPORT

Prepared under Contract No. GS-10F-0033M / Order No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013, Tasking N058

DRG LEARNING, EVALUATION, AND

RESEARCH ACTIVITY

IMPACT EVALUATION OF THE OBIRODH –

ROAD TO TOLERANCE YOUTH

LEADERSHIP TRAINING PROGRAM IN

BANGLADESHI UNIVERSITIES

FINAL REPORT

July 2021

Prepared under Contract No. GS-10F-0033M / Order No. AID-0AA-M-13-00013, Tasking N058

Submitted to:

Mousumi Sarkar, COR

Submitted by:

Peter Vining, NORC Principal Investigator (New York University)

Cyrus Samii, NORC Principal Investigator (New York University)

Michael Gilligan, NORC Principal Investigator (New York University)

Contractor:

NORC at the University of Chicago

Attention: Matthew Parry, Program Manager

3450 East-West Highway, Suite 800

Bethesda, MD 20814

Telephone: (301) 634-5444

E-mail: Parry-[email protected]

DISCLAIMER

The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United

States Agency for International Development or the United States Government.

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities | i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACRONYMS III

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1

1. INTRODUCTION 4

2. VIOLENT EXTREMISM IN CONTEMPORARY BANGLADESH 5

3. BACKGROUND ON PREVENTING AND COUNTERING VIOLENT EXTREMISM (P/CVE)

PROGRAMS 11

4. THEORY OF CHANGE 14

FACTORS INHIBITING THE IMPACT OF BYSTANDER INTERVENTION TRAINING 18

ADAPTING THE BYSTANDER INTERVENTION MODEL TO REDUCE VIOLENT EXTREMISM

ANTECEDENT BEHAVIORS 20

5. IMPACT EVALUATION METHODOLOGY 21

INTERVENTION DESIGN: ADAPTING BIT TO BANGLADESHI UNIVERSITIES 22

SITE SELECTION, PARTICIPANT RECRUITMENT, AND RANDOMIZATION PROCEDURE 24

SAMPLE SIZE, DATA COLLECTION STRATEGY, AND TIMELINE 26

OUTCOMES OF INTEREST AND MEASUREMENT STRATEGY 28

NORMS 29

SKILLS 32

CONFIDENCE AND SELF-ASSESSED COMPENTENCE TO ACT 33

WILLINGNESS TO INTERVENE 34

PEER LEADERS VS TRADITIONAL AUTHORITY FIGURES 35

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS COVARIATE BALANCE 35

6. DATA ANALYSIS 38

7. RESULTS 41

NORMS 41

SKILLS 44

CONFIDENCE AND SELF-ASSESSED COMPETENCE TO ACT 45

WILLINGNESS TO INTERVENE 46

PEER LEADERS VS TRADITIONAL AUTHORITY FIGURES 48

PLACEBO OUTCOMES: DO NORMS AND CONFIDENCE TO ACT CHANGE WITH RESPECT

TO UNRELATED TOPICS 51

LIMITATIONS 52

SUMMARY 53

8. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS 54

APPENDIX A. 56

APPENDIX B. 63

TABLES

Table 1: Participating Public and Private Universities in Dhaka and Rajshahi 24

Table 2: Data Collection Timeline 28

Table 3: Pre-Treatment Covariate Balance 37

Table 4: Effects of Programming and Tolerance BIT Program on Norms of Tolerance 56

Table 5: Effects of Programming and Tolerance BIT Program on Religious Tolerance (Web-

Based Stimulus Activity) 56

Table 6: Effects of Programming and Tolerance BIT Program on Rejection of Violence 57

Table 7: Effects of Programming and Tolerance BIT Program on Internalized Skills 57

Table 8: Effects of Programming and Tolerance BIT Program on Confidence to Act 58

Table 9: Effects of Programming and Tolerance BIT Program on Willingness to Intervene 58

Table 10: Participant Identification with Peer Leaders, compared to Traditional Authority Figures,

among Those Enrolled in Tolerance BIT Program 59

Table 11: Effect of Peer Leaders, compared to Traditional Authority Figures, on Participant

Evaluation of Social Environment among Those Enrolled in Tolerance BIT Program 59

Table 12: Effect of Peer Leaders, compared to Traditional Authority Figures, on Participant

Identification with Program Goals among Those Enrolled in Tolerance BIT Program 59

Table 13: Impact of Peer Leaders, compared to Traditional Authority Figures, on Outcomes of

Interest among Those Enrolled in Tolerance BIT Program 60

Table 14: Summary Statistics for Outcomes of Interest 60

Table 15: Standardized Baseline Covariate Balance by Attrition 62

Table 16: Gross Effect of Programming and Effect of Tolerance BIT Curriculum on Placebo

Norms and Confidence Outcomes. 62

FIGURES

Figure 1: Pathways from BIT Programming to Willingness to Intervene 17

Figure 2: Effects of Programming and Tolerance BIT Curriculum on Norms of Tolerance 42

Figure 3: Effects of Programming and Tolerance BIT Curriculum on Norms of Religious Group

Status Measures 42

Figure 4: Effects of Programming and Tolerance BIT Curriculum on Rejection of Violence and

VEOs 43

Figure 5: Effects of Tolerance BIT Curriculum on Common Knowledge Assessment Scores 44

Figure 6: Effects of Programming and Tolerance BIT Curriculum on Internalized BIT Skills 45

Figure 7: Effects of Programming and Tolerance BIT Curriculum on Confidence Act 46

Figure 8: Effects of Programming and Tolerance BIT Curriculum on Willingness to Intervene 47

Figure 9: Participant Identification with Peer Leaders, compared to Traditional Authority

Figures, among Those Enrolled in Tolerance BIT Program 48

Figure 10: Participant Identification with Social Environment of Programming, comparing Peer

Leaders to Traditional Authorities among Those Enrolled in Tolerance BIT Program 49

Figure 11: Participant Identification with Programming Goals, Comparing Peer Leaders to

Traditional Authorities, among Those Enrolled in Tolerance BIT Program 50

Figure 12: Impact of Peer Leaders, compared to Traditional Authority Figures, on Outcomes of

Interest among Those Enrolled in Tolerance BIT Program 51

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| ii

ACRONYMS

BIT Bystander Intervention Training

CVE Countering Violent Extremism

DID Difference in Differences

DIM Difference in Means

GTD Global Terrorism Database

IE Impact Evaluation

IPA Innovations for Poverty Action

ITT Intent-to-Treat

LGAP Local Government Accountability and Performance

LGBT Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender

NPC No-program Control

P/CVE Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism

RCT Randomized Controlled Trial

SMS Short Message Service (text messaging using standard communication protocols)

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

USAID United States Agency for International Development

USD U.S. Dollar

VEO Violent Extremist Organizations

WGI Worldwide Governance Indicators

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| iii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This report presents the results of a rigorous randomized impact evaluation of a youth leadership

training program aimed at preventing violent extremism in Bangladesh. The program was part of the

broader USAID-sponsored Obirodh: Road to Tolerance project in Bangladesh, which aimed to support

Bangladeshi civil society actors in their work to promote tolerance and mitigate the spread of

extremism. The USAID Center for Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance (DRG) worked with the

USAID Bangladesh mission to commission an evaluation as part of the DRG Learning, Evaluation, and

Research (DRG-LER) Activity. The key finding from the evaluation was that the program significantly

improved participants’ norms of tolerance and their expected willingness and capacity to intervene safely

and effectively when they witness intolerant and extremist behavior. Thus, the program represents a

promising approach to addressing violent extremism that could be applied in a variety of contexts.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

Preventing and countering violent extremism (P/CVE) suffers from a needle-in-a-haystack problem:

becoming a violent extremist is a very low probability event. Therefore, targeting programs on at-risk

persons wastes resources on de-radicalization programs for people who never would have been

radicalized in the first place. In addition, strategies attempting to deter or use surveillance on entire “at-

risk” groups in an aggressive and coarse manner may do more to alienate members of that group,

undermining the potential for enlisting the support of those who may actually have no interest in violent

extremism. Moreover, the context in which a P/CVE program is being implemented may greatly

constrain the menu of feasible strategies. Approaches taken from within industrialized liberal

democracies that rely on the police, justice system, or youth service institutions may not be appropriate

in contexts where civil liberties are constrained or police forces are partisan or abusive. The program

examined by this evaluation sought to avoid these pitfalls by focusing instead on making the social

climates in which violent extremists might recruit less hospitable to violent extremism. It did so by

training youth to recognize expressions of intolerant and extremist views and to intervene safely and

effectively to counter such expression. Specifically, rather than attempting to identify and neutralize

individual extremists, this program attempts to enable those who do not espouse intolerant or

extremist views to contribute to a general climate in which expressions of intolerance or violence

would be countered. By training individuals to publicize and reinforce norms against extremist views and

behaviors, the programming is meant to both decrease the likelihood of extremist expression among

those holding attitudes that might lead them to express it, and empower others who hold attitudes

opposed to extremist behaviors to further reinforce norms against it. The program thus offers a new

approach to P/CVE not relying on surveillance or aggressive police action, and an approach to which

broader segments of the population falsely assumed to be “at-risk” may be more receptive and

responsive.

The youth leadership training program focused on university students because the majority of those

involved in recent violent attacks in Bangladesh have been university graduates with educated, middle-

class origins. We selected six universities as sites for the study, three in Dhaka and three in Rajshahi.

The program drew inspiration from “bystander intervention training” (BIT) programs implemented in

other contexts to address anti-social behaviors. The program trained university students to identify and

intervene in situations in which their peers expressed extreme intolerance or aggression toward

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| 1

vulnerable groups or minorities, with a particular focus on religion and gender. The impact evaluation

used a randomized controlled trial design, testing the pro-tolerance BIT curriculum against a placebo

curriculum and against a no-program control group. This allows the evaluation to estimate both the

gross effect of the program, which involves both novel social interactions and generic prompts to think

critically along with the content of the curriculum, and the effect of the BIT curriculum itself. The

evaluation also examined whether it would be more effective to have peer leaders (those similar to the

trainees) rather than traditional authority figures (professors, in this case) deliver the training. The study

used surveys and a web-based stimulus activity to measure attitudes, the internalization/retention of

knowledge and skills, and behavioral intentions.

FINDINGS

The program led to improved norms of tolerance among participants, although much of this

improvement appears attributable to the nature of the social interactions created by the program and

the generic prompts to get subjects to think critically rather than the BIT curriculum itself. It is plausible,

for example, reduced sexism observed among participants is attributable to the mixed-gender nature of

the programming, rather than the BIT curriculum content. We can distinguish these sources of the

effects when we compare how BIT program participants fared relative to those who received no

program at all and relative to those who received a placebo curriculum (that focused on health and

sanitation). The BIT program successfully improved participants’ skills and competence to intervene in a

potentially effective way when presented with scenarios of aggression, with similar caveats suggesting

these effects are partially driven by social interactions within the program. The BIT program also

improved participants’ eagerness and confidence to act when they witnessed intolerance, and these

effects appear mainly to be derived from the content of the BIT curriculum itself. Finally, we find the BIT

program increased participants’ willingness to intervene (the primary outcome of interest, as measured

by behavioral intentions in response to vignettes) in a variety of perpetrator-victim scenarios.

Importantly, the curriculum was able to increase tolerant attitudes not only towards groups directly

addressed by the curriculum (women, non-Muslims), but also in an area our implementing partner

deemed too controversial to include, namely LGBT rights. Students appear to have extended lessons

learned on tolerance to this latter group even though the curriculum did not directly address it.

Moreover, the program increased willingness to intervene against violent extremism, even though the

curriculum was focused mostly on positive reinforcement of tolerance and anti-violence norms.

With regard to peer versus traditional authority facilitators, the evidence suggests on the whole, the

traditional authority facilitators were more effective. These findings suggest a “social climate” strategy,

i.e., a strategy designed to empower and encourage those already holding tolerant attitudes to safely

protect and promote norms of tolerance within their social milieus, may be potentially effective for

P/CVE purposes, especially in contexts with heightened political sensitivity and frequent rights violations.

While encouraging, these findings do not shed light on the longer-term impact of such programming, or

whether changes within the social microclimates of participants have endured following, for example, the

disruptions of the Covid-19 pandemic. In addition, while this program was designed as a “megadose”

(about 28 hours) of BIT when compared to similar initiatives, it is unclear to what extent scaling the

programming (either through larger class sizes and/or shorter duration) would potentially erode efficacy.

Finally, although the research design sought to minimize demand effects and social desirability bias in

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| 2

survey responses and activities, it is nevertheless possible some of the attitudinal measures we use

reflect these issues.

IMPLICATIONS

The implications of our results are that indirect, “social climate” strategies are a compelling approach to

address violent extremism. While further study should be conducted on the durability of these

interventions before strong policy conclusions are drawn, the BIT curriculum implemented in

Bangladesh was successful and should be considered for other contexts. To that end, this evaluation’s

findings suggest some lessons learned for future P/CVE endeavors. In future programming, relying on

peer facilitators appears to be somewhat risky because peer facilitators appeared to be less adept

instructors. Thus, we recommend relying on professional instructors for future training programs like

the one studied here. Second, this evaluation suggests that a BIT approach focusing on empowering

those holding tolerant attitudes to safely protect and promote tolerant social norms can cultivate

tolerant attitudes toward groups too politically or socially sensitive and controversial to address

directly.

The program in this study was designed to make the environment less hospitable to violent extremists

by training members of civil society to recognize intolerant and extremist views and take appropriate

action. The program was successful in meeting these goals, producing significant improvements in

participants’ norms of tolerance and their willingness and ability to intervene safely and effectively when

they witness intolerance and extremism. These improvements were reflected in survey instruments

used to measure attitudinal changes, skills/knowledge retention and application using aptitude measures,

and behavioral intentions in response to vignettes.

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| 3

1. INTRODUCTION

As part of the DRG Learning, Evaluation, and Research (DRG-LER) Activity, USAID requested that

NORC design and implement an impact evaluation (IE) to study a youth leadership training program

aimed at preventing violent extremism in Bangladesh. The program was part of the broader USAID-

sponsored Obirodh: Road to Tolerance project in Bangladesh, which aimed to support Bangladeshi civil

society actors in their work to promote tolerance and mitigate the spread of extremism. The youth

leadership training program focused on university students, given that the majority of those involved in

recent violent attacks in Bangladesh have been university graduates with educated, middle class origins.

Countering violent extremism is fraught with the reality that such extremism is, by its nature, rare, and

strategies that attempt to deter or use surveillance on presumed “at-risk” communities in an aggressive

and coarse manner may do more to alienate those who have no interest in violent extremism than

identify or temper those who are genuinely at-risk. Such programs, like the New York Police

Department’s “Muslim Surveillance and Mapping Program” were found to be both illegal in profiling faith

communities and also stifling of potential cooperation from community members. We discuss examples

of such approaches and their negative consequences in an overview of P/CVE strategies found in section

3 of this report.

Working with university students in Bangladesh, the youth leadership training program sought to avoid

such pitfalls by using positive reinforcement of tolerance and anti-violence norms to cultivate a social

“climate” against extremism. The program drew inspiration from “bystander intervention training” (BIT)

programs implemented in other contexts, such as universities, secondary schools, and organized sports,

to address anti-social behaviors. It sought to train university students to identify and intervene, in ways

safe for themselves and others, in situations in which their peers expressed extreme intolerance or

aggression toward vulnerable groups or minorities, with a particular focus on religion and gender. The IE

used a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design, testing the pro-tolerance BIT curriculum against a

placebo curriculum and against a no-program control group. The placebo was designed as a parallel

leadership development program meant to build critical thinking skills with a focus on civic issues

unrelated to tolerance. Using a placebo allowed the evaluation to estimate both the gross effect of the

program, which involves both novel social interactions in a programmatic context and generic prompts

to think critically, and the valued added by the content of the curriculum per se. The evaluation also

studied whether it would be more effective to have peer leaders (those similar to the trainees) leading

sections of the programming as “facilitators,” rather than traditional authority figures (i.e., professors in

this case).

This report presents the results of the IE. We find that the BIT program led to improved norms of

tolerance among participants, although much of this improvement appears attributable to the nature of

the social interactions and generic prompts to think critically that were created by the program. We

also find that the BIT program successfully improved participants’ skills and judgement (competence)

when presented with scenarios of aggression, with similar caveats suggesting that these effects are

partially driven by the general social interactions within the program. Furthermore, we find that the BIT

program improved eagerness and confidence to act among participants, which we attribute mainly to the

focused curriculum of the BIT program. Finally, we find that the BIT program led to willingness to

intervene (the primary outcome of interest) when participants were presented with a variety of

perpetrator-victim scenarios. Presumably, willingness to intervene is driven by the effect of confidence

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| 4

and self-assessed competence to act among BIT participants. The results are promising for indirect,

social climate strategies to counter violent extremism.

With respect to the aforementioned outcomes (norms, competence, confidence, and willingness to

intervene), we found suggestive evidence that peer leaders may be less effective than traditional

authority figures (namely, professors) at leading a program of this nature, although these differences

were not large. Differences between each type of facilitator appear more pronounced regarding

participant perceptions of the facilitator leading their groups, which may be driving small differences in

the other outcomes of interest. Not surprisingly, traditional authority figures (i.e., professors) were

significantly more likely to be seen as experienced, while peer leaders were seen as youthful.

Interestingly, the traditional authority figures were perceived as more approachable than the peer

leaders. These results speak to the importance of experience and professional skill in administering

training programs.

In section 2 of this report (below), we begin with a discussion of the context, describing the nature of

violent extremism in contemporary Bangladesh. Violent extremism in Bangladesh regularly involves

educated young adults, which motivates our focus on university students. In section 3, we review

current strategies for countering violent extremism, explaining why we think the bystander intervention

training approach is most suitable for university students in the present context. In section 4, we present

the theory of change for the youth leadership training program. Section 5 describes the research design

and data collection plan for the IE. Section 6 then present our statistical analysis of the results of the

evaluation. A concluding section 7 summarizes what we have learned, derives policy implications, and

offers suggestions for further research.

2. VIOLENT EXTREMISM IN CONTEMPORARY BANGLADESH

Violent extremism in Bangladesh has increased noticeably in recent years, threatening development goals

and political stability in the world's eighth most populous country. The Institute for Economics and

Peace’s Global Terrorism Index records an increase on its 10 point “Impact of Terrorism" scale from 4.1

to 5.9 between 2012 and 2015 in Bangladesh.

1

Estimates of the number and severity of extremist attacks

in recent years vary, depending on the data source and criteria used in defining such attacks. One

conservative estimate claims that the 2013-2015 period was marred by at least 47 major extremist

attacks, killing 54 and injuring hundreds more, in contrast to just 92 attacks during the entire decade

prior

2

. The number of known violent extremist organizations (VEOs) also varies widely, as groups often

merge, splinter, rebrand, or operate in conjunction with non-violent political wings; estimates have

ranged from 12 to 70 organizations.

3

An independent analysis of data provided by the Global Terrorism Database (GTD)

4

, which records

deliberate acts of violence for political, religious, economic or social purposes, suggests that five major

VEOs have carried out 114 attacks, killing at least 127 people and injuring another 348 people within

1

Riaz, A. (2016a). Who are the Bangladeshi ‘Islamist Militants? Perspectives on Terrorism, 10 (1).

2

Rahman, M. A. (2016). The Forms and Ecologies of Islamist militancy and terrorism in Bangladesh. Journal for Deradicalization,

(7), 68-106.

3

Ahsan, Z. (2005). Trained in foreign lands: The spread inland. The Daily Star, 21 August 2005, and Rahman, M. A. & Kashem,

M. B. (2011). Understanding religious militancy and terrorism in Bangladesh. Dhaka: ICA Bangladesh.

4

National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (Start). (2017). Global Terrorism Database

[Data File]. Retrieved from https://www.start.umd.sdu/gtd.

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| 5

Bangladesh from 2013-2016. These include VEOs with an international presence (Islamic State in

Bangladesh and Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent, known within Bangladesh as Ansar-al-Islam), as well

as Bangladeshi organizations (Ansarullah Bangla Team, Jamaat-E-Islami Bangladesh, and Jama'atul

Mujahideen Bangladesh). These organizations are usually responsible for the most high-profile and mass-

casualty events, such as the July, 2016 Holey Cafe attack and hostage incident, which killed 28 people

and wounded another 30. This attack was claimed by Islamic State, and likely also involved Jama'atul

Mujahideen Bangladesh.

Many VEO-sponsored attacks in Bangladesh have targeted individuals rather than institutions, usually for

sectarian purposes, and as part of an ongoing campaign to intimidate and terrorize different minority

groups within the country. Targets have included ethnic, religious and sexual minorities, as well as

foreigners, academics, journalists, and those deemed to have committed acts of blasphemy or apostasy

against extremist interpretations of Sunni Islam. GTD data indicate that of the 59 lethal VEO-related

attacks recorded from 2013-2016, at least 35 were murders of targeted individuals; victims have ranged

from Hindu, Shia and Christian religious leaders

5

to university professors,

6

atheist and secular bloggers,

7

lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights activists,

8

foreign aid workers,

9

and others. The

April, 2016 murder of LGBT activist and US Embassy employee Xulhaz Mannan along with colleague

Mahbub Rabbi Tonoy by Ansar-al-Islam is a prototypical example of these targeted killings, which are

often preceded by death threats and carried out by groups of men wielding knives, machetes, or other

crude weapons.

In addition to these high-profile attacks carried out by or on behalf of known extremist organizations,

Bangladesh has also experienced a troubling wave of sectarian violence carried out by individuals or

unorganized small groups against the aforementioned minority groups. The Global Terrorism Database

contains information on many attacks whose perpetrators remain unidentified, but clearly fall within this

narrative. Oftentimes, these attacks include difficult-to-prosecute property crimes (such as arson) and

are carried out using machetes, knives, rocks, petrol bombs and crude incendiary devices. Examples

from the 2013-2016 period include attacks against Sufi Muslims

10

, Hindu temples

11

and homes

12

, as well

as religious minority leaders.

13

Profiles of the individual militants themselves contradict a common narrative that they tend to be

uneducated and unskilled. Many arrestees from recent plots and attacks have been university graduates

with educated, middle class origins, suggesting that economic deprivation offers limited explanatory

power for why individuals join VEOs.

14

An analysis of the socio-demographic profiles of Bangladeshi

5

"IS 'beheads' Hindu priest in Bangladesh," BBC, February 21, 2016; "Top Shia Preacher Killed in IS Claimed Attack in

Bangladesh," Outlook India, March 15, 2016; "Bangladesh: Another Hindu priest murdered," The Daily Star Online, July 1, 2016;

"B'desh Christian priest attacked in his house by armed men," Deccan Herald, October 6, 2015.

6

"Professor murder: Militants claim responsibility on Facebook," Dhaka Tribune, November 16, 2014.

7

"Ananta Bijoy Das Hacked To Death In Bangladesh In Third Such Killing Of Atheist Bloggers," International Business Times,

May 12, 2015; "Second blogger hacked to death this year in Bangladesh," Reuters, March 30, 2015.

8

"Islamist Militants Suspected in Killing of Gay Rights Activist in Bangladesh," The New York Times, April 26, 2016.

9

"Australia: Bangladesh Opposition officials among seven charged over Italian aid worker murder," ABC Online, June 28, 2016.

10

"3 Sufi Muslims attacked in B’desh," New Delhi Pioneer, July 30, 2016.

11

"Dhaka: Fresh Attacks on Hindu Temples Create 'Widespread' Panic Among Minorities," The Daily Star Online, March 9,

2013.

12

"Bangladesh: 10 Hindu houses torched in Dinajpur," Dhaka Tribune Online, December 4, 2016.

13

"Leader of religious minority forum attacked in Bangladesh," Deutsche Presse-Agentur, November 24, 2015.

14

Rahman, M. A. (2016). The Forms and Ecologies of Islamist militancy and terrorism in Bangladesh. Journal for Deradicalization,

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| 6

militants arrested from January 2014 through June 2015 is consistent with this claim; the majority of

them are young, well-educated men from middle class backgrounds. Out of 112 alleged militants

arrested during this time period, 52 were men between the ages of 18 and 30. Out of 65 for whom

occupations could be identified, 53 held professional or middle-class jobs/career tracks. Nine were

university students, nine were engineers, five were teachers, and the rest were a variety of other

middle-class professions including business owners, travel agents, IT experts, and office clerks. In

contrast, only 13 of the 65 held jobs in working class or manual labor positions. Regarding education,

nearly all of the 53 individuals in middle class career tracks hold or are pursuing college degrees, and

several hold advanced degrees. Only 13 were madrassa students or teachers.

15

Evidence from student and school administrator focus groups can provide some insight into possible

explanations for the aforementioned patterns in VEO perpetrators and targets. Focus groups of

university and post-secondary level madrassa students held by Breakthrough Media found that

intolerance was fostered by the Bangladeshi secondary education system, due to divisions that the four

different types of secondary schools (English, Bangla, Quomi madrassa and Aliya madrassa) create and

exacerbate along lines of gender, wealth, religion, and religiosity, without building a sense of empathy for

different backgrounds. In addition, all four school types were found to promote a religiously/culturally

narrow definition of Bangladeshi national identity that is closely tied to Sunni Islam. These findings from

student focus groups were corroborated by a survey of school administrators in which 72% responded

that the “diverse streams of education [i.e., the four different school types] contribute to radicalization

in Bangladesh.”

16

Apparently, despite universities being more integrated than the secondary schools, the

economic and cultural divisions originating in the primary and secondary education systems persist

within the university system while the financial and social vulnerabilities of university students – who are

typically facing academic pressures, and the pressures of early adulthood and identity formation in the

new and unfamiliar settings of a university campus, potentially with few preexisting social connections-

also make them more susceptible to outside influences and pressures.

17

Country-wide survey evidence from Bangladesh also suggests a concerning political and social

environment. Although three-quarters of respondents in a 2012 country-wide survey of Bangladeshi

Sunni Muslims felt that suicide bombings and other attacks against civilian targets were rarely or never

justified, roughly a quarter responded that they were sometimes or often justified; these levels of

support for suicide attacks were also found to be substantially higher than those within the broader

region (including Pakistan, Malaysia and Indonesia).

18

Further analysis of the survey reveals a population that appears to be split between strict and moderate

cultural interpretations of Sunni Islam with respect to a variety of issues. While a majority of

respondents stated that women should have the right to divorce their husbands and choose whether to

wear the hijab, sizable minorities (about 30%) responded that they should not; moreover, a sizable

minority (35%) responded that honor killings of women by family members are often or sometimes

justified. Regarding attitudes towards minority groups, Sunni Muslims in Bangladesh tend to be

(7), 68-106.

15

Riaz, A. (2016). Who are the Bangladeshi ‘Islamist Militants? Perspectives on Terrorism, 10(1).

16

Breakthrough Media. (2017). “Research Paper for Credible Voices Bangladesh.” Report prepared for USAID.

17

Ibid.

18

Fair, C. Christine, Ali Hamza, and Rebecca Heller. “Who Supports Islamist Militancy in Bangladesh: What the Data Say?”

Available at SSRN 2804275 (2016).

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| 7

conservative. About 70% responded that homosexual behavior was “morally wrong,” 68% responded

that they would be “not too” or “not at all” comfortable if a son of theirs someday married a Christian,

and about 16% did not consider Shia to be Muslims. Regarding attitudes towards the West, only about

17% responded that Western media have hurt morality within Bangladesh.

19

Regarding attitudes towards

their fellow Muslims, majorities or near-majorities favored the stoning of people who commit adultery

(52%), punishments like whipping or cutting off of hands for the crimes of theft or robbery (50%), and

the death penalty for people who leave the Muslim religion (44%).

20

A more recent set of surveys conducted between 2012-2014 commissioned by PACOM and carried out

by Nielson-Bangladesh roughly corroborates many of the findings in the 2012 Pew study regarding

perceptions on violence and foreign countries; surveys in 2012, 2013, and 2014, all found that roughly

half of respondents agreed that the use of violence was acceptable “against immoral people,” and “to

maintain the culture and traditions of society,” while between 80-90% agreed that violence was

acceptable “in defense of one’s religion.” Regarding perceptions of Western countries, less than half of

respondents reported positive perceptions of the United States’ influence on Bangladeshis’ way of life,

while less than a quarter reported positive perceptions of the United Kingdom.

21

Finally, recent work has also suggested that many of the aforementioned patterns both in the individuals

recruited/targeted by VEOs, as well as the prevailing social/political context, are in part exacerbated by

the proliferation of social media use (especially Facebook) in an environment that is still characterized by

significant levels of illiteracy and a lack of critical thinking education.

22

Both a SecDev study on behalf of

UNDP Bangladesh and the Breakthrough Media focus groups reported that Facebook (which about 80%

of the population use) has contributed both to increasing “cultural tribalism” via information echo

chambers, while also offering a tool for VEO messaging towards vulnerable populations, despite findings

that very few Bangladeshis actually seek out extremist pages and content. Interestingly, Madrassa student

focus groups reported that they viewed news shared on Facebook as more trustworthy than “the

media,” due to their ability to self-select their content.

23

Extremist groups make use of this cultural

tribalism in developing graphical/video content designed to provoke emotional reactions and reinforce a

sense of victimhood among Sunni Muslims at the hands of purportedly hostile minority groups and

foreign powers, often by connecting them to injustices and conflict narratives abroad.

24

The aforementioned context and profiles of those carrying out recent extremist attacks suggest that

economic “countering violent extremism” (CVE) interventions (i.e., jobs programs, cash transfers, etc.),

which have been attempted in numerous other contexts with frequently unconvincing results, are likely

ill-suited as effective strategies for the Bangladeshi setting.

25

Given that most recent perpetrators have

19

The Pew Research Center. (2012). The World’s Muslims [Data File]. Retrieved from http://www.pewforum.org/datasets/2012/.

20

Ibid.

21

“Vulnerability to Extremist Influence in Bangladesh.” (June, 2012). Report commissioned for the United States Pacific

Command (PACOM).

22

The SecDev Group. (2016). “Violent Extremist Narratives and Social Media in Bangladesh.” Report commissioned by the

UNDP Bangladesh.

23

“Vulnerability to Extremist Influence in Bangladesh” p. 7.

24

“Violent Extremist Narratives and Social Media in Bangladesh.” (p. 7); “Bangladesh Country Needs Assessment: Drivers of

Radicalization and Recruitment, and Community Resilience to Violent Extremism.” (March, 2016). Assessment conducted for

the Global Community Engagement and Resilience Fund by the Royal United Services Institute.

25

For a more thorough discussion of economic CVE interventions and their merits, see Gilligan, M., Samii C., and Vining, P.

(2017). Evidence Review Paper: Countering Violent Extremism. Paper prepared for USAID Impact Evaluation Clinic, March 27-

31, 2017.

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| 8

not only been gainfully employed, but are often educated members of the middle class, it is far more

likely that CVE efforts need to incorporate a psychosocial understanding of radicalization and prevention

efforts. Specifically, such efforts should be premised on the understanding that individuals who are

successfully targeted for recruitment by VEOs often have the same prosocial dispositions as those who

become involved in other social movements and organizations; by becoming involved in VEOs, they are

attempting to fulfill their psychosocial needs and desires in ways that traditional kinship, peer and

community ties are apparently unable to. While involvement in VEOs carries potentially high costs to

those individuals, the payoffs of fulfilling a “quest for significance” can outweigh those costs, especially if

the broader political/social context reduces barriers to entry and the risks of punishment.

26

It is well known that individuals are more willing to sacrifice their own welfare in order to pursue

feelings of efficacy in service of a cause, oftentimes in response to events that lead to feelings of

“significance loss."

27

Such significance loss events may include sources of trauma that cause feelings of

loss, shame, humiliation, deprivation, disenfranchisement, vulnerability, reduced self-worth,

isolation/loneliness, conflicted identity, and/or disillusionment with one’s current social role.

28

Such

feelings lead to cognitive openings within the individual, i.e., an openness to reorientation of their beliefs.

In order for an individual’s quest for renewed significance to manifest as participation in violent

extremism, however, these psychological motivations require (1) “moral warrants" that justify the use of

violence, as well as (2) social processes of introduction and involvement to exploit the identified

cognitive openings. VEOs thus step in to fulfill these necessary conditions by providing moral/ideological

warrants for violence in socially empathetic settings, in addition to identifying, grooming, and at times

even creating vulnerable individuals.

29

Crucially, social affirmation is understood to be a big part of how

participation in violent extremism fulfills the need for significance. The type of climate strategy studied in

the current IE attempts to create a counterweight to social affirmation through extremism.

Introduction to VEOs often occurs via kinship and friendship networks, although some perpetrators

were found to have “self-radicalized.” Introduction is usually gradual, starting with passive participation

in informational events or low-risk activism activities. Assuming that the VEO is interested in more

involvement from a potential recruit, further indoctrination occurs via radicalized elites, usually in the

context of a new and supportive community. This often occurs concurrently with isolation from and

rejection of moderating influences and old social ties. As a part of this socialization process, sacrificial

behavior may be required as a signal of reliability for future group contributions.

30

A wide variety of programs and initiatives have attempted to disengage and deradicalize individuals from

VEOs. Almost exclusively, these programs have targeted those who have either already committed, or

were at imminent risk of committing an act of violence. The choice of this target population is largely

due to the difficulties of detecting and targeting interventions at those in earlier stages of radicalization.

Most deradicalization programs have attempted to leverage some combination of implicit interventions

26

Ibid.

27

Dugas, M., Bélanger, J. J., Moyano, M., Schumpe, B. M., Kruglanski, A. W., Gelfand, M. J., … & Nociti, N. (2016). The quest for

significance motivates self-sacrifice. Motivation Science, 2(1), 15.

28

Bushman, B. J. (Ed.). (2016). Aggression and Violence: A Social Psychological Perspective. Psychology Press; Agnew, R. (2010). A

general strain theory of terrorism. Theoretical Criminology, 14(2), 131-153.

29

Kruglanski, A. W., Gelfand, M. J., Bélanger, J. J., Sheveland, A., Hetiarachchi, M., & Gunaratna, R. (2014). The psychology of

radicalization and deradicalization: How significance quest impacts violent extremism. Political Psychology, 35(S1), 69-93.

30

Berman, E. (2011). Radical, religious, and violent: The new economics of terrorism. MIT press; Wiktorowicz, Q. (2005).

Radical Islam rising: Muslim extremism in the West. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| 9

(i.e., those addressing the underlying reasons for joining) and explicit interventions (i.e., those countering

the radicalized worldview).

31

The efficacy of these programs is difficult to evaluate, due to: (1) a lack of

RCTs used to evaluate their effects, (2) strong demand effects leading participants to report being

“cured” (which often leads to leniency, reduced sentencing, and/or other incentives), and (3) because

post-program monitoring makes participants less-appealing for risk-averse VEOs to approach for

recidivism.

One example of a series of interventions designed to address radicalization at earlier stages was the

German HAYAT program, which seemed to offer a fruitful model for preventing highly radicalized (but

not yet violent) individuals from emigrating to fight on behalf of jihadist groups in Syria/Iraq during the

latter 2010’s. The program featured an innovative, community-based approach that sought to leverage

friend and family networks in order to deter a radicalized individual from departing.

32

Still, the success of

an individually-focused model for those at earlier stages of radicalization presumes a social and political

context in which such attitudes and behaviors noticeably depart from prevailing social norms, are

detectable by the individual’s social networks, and are therefore likely to put the individual at risk of

ostracization and/or harm should they become further involved in VEO activity. Moreover, the success

of such a model presumes that safe “off-ramps” are available for the individual’s close network to pursue

in order to intervene without risking legal consequences or ostracization for the radicalized individual or

themselves. In contexts where individual rights are regularly violated, these conditions may not be in

place.

Overall, while the psychosocial perspective and potential interventions derived from it offers a nuanced

post-hoc explanation for why individuals are targeted by, join, and carry out acts of violence on behalf of

VEO’s, it offers frustratingly few prescriptions for effective and targeted approaches to prevent or

counter violent extremism at the individual level, and at stages of involvement that precede imminent

plots and acts. Most of the aforementioned findings are based on studies of individuals who have either

been arrested/imprisoned following VEO-related offenses,

33

or who have voluntarily disengaged/de-

radicalized and agreed to share their accounts with researchers. Other findings are based on voluntary

accounts given by radicalized, but explicitly non-violent individuals in contexts where such organization

and activism is legal as protected speech.

34

Finally, because the population of potentially at-risk individuals is enormous while the population of

those who actually radicalize, join, and go on to commit acts of violence is so small, it is likely more

useful to target early-stage preventing and countering violent extremism (P/CVE) approaches at the

community level, rather than at the individual level. Specifically, rather than attempting to identify and

treat “at-risk individuals,” strategies that attempt to address social norms regarding behaviors and

31

Kruglanski et al. (2014); Refer to Gilligan, Samii and Vining (2017) for examples.

32

Koehler, D. (2013). Family Counselling as Prevention and Intervention Tool Against ‘Foreign Fighters’. The German ‘Hayat’

Program. Journal Exit-Deutschland. Zeitschrift für Deradikalisierung und demokratische Kultur, 3, 182-204.

33

See, for example, Kruglanski, A. W., Gelfand, M. J., Bélanger, J. J., Sheveland, A., Hetiarachchi, M., & Gunaratna, R. (2014). The

psychology of radicalization and deradicalization: How significance quest impacts violent extremism. Political Psychology, 35(S1),

69-93; Bélanger, J. J., Caouette, J., Sharvit, K., & Dugas, M. (2014). The psychology of martyrdom: making the ultimate sacrifice

in the name of a cause. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(3), 494.

34

See, for examples, Wiktorowicz, Q. (2005). Radical Islam rising: Muslim extremism in the West. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers;

Kenney, M., Horgan, J., Horne, C., Vining, P., Carley, K. M., Bigrigg, M. W., ... & Braddock, K. (2013). Organisational adaptation

in an activist network: Social networks, leadership, and change in al-Muhajiroun. Applied Ergonomics, 44(5), 739-747.

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| 10

attitudes towards groups targeted by VEOs are likely to offer an approach to P/CVE to which those “at-

risk” and their close-networks may be more receptive and responsive.

3. BACKGROUND ON PREVENTING AND COUNTERING

VIOLENT EXTREMISM (P/CVE) PROGRAMS

A variety of P/CVE programs have been implemented by governments and communities throughout the

post-9/11 period to date.

35

These programs can be loosely defined as those designed to prevent or

mitigate violent extremism by using a range of soft policy interventions

36

that target individuals, groups,

communities and/or societies. While many of these initiatives have been successfully implemented from

a programmatic standpoint,

37

very few of them have been implemented in such a way that enables

policymakers to determine whether they actually work- i.e., whether they achieve their goal of

preventing and/or countering radicalization and involvement in VEOs. Among the few P/CVE programs

that have included an evaluation component, virtually none have been designed in such a way that

enables causal inference from program effects. A 2017 systematic review of 73 CVE studies, for

example, found that only 14 were “effect evaluations” (i.e., those addressing causal effects of the

program), of which only 5 were quantitative IEs, and only 2 of which were quasi-experimental.

38

To our

knowledge, no P/CVE programs have yet been implemented as RCTs, which are the gold standard for

evaluating program effects.

The challenges to rigorous evaluation of P/CVE program effects are numerous, but fairly well-known.

First among these challenges is correctly reaching “at-risk” individuals or groups, without generating

unacceptable levels of false positives and/or exacerbating the problem by alienating or stigmatizing them.

Attempts to correctly profile “at-risk” individuals have largely proven fruitless, and have sometimes

backfired in the form of racial or religious profiling. The United Kingdom’s “Prevent” program, for

example, was largely blamed for resulting in the stigmatization of UK Muslims who expressed

conservative viewpoints; the mere inclusion of such individuals in programming designated as

“preventing violent extremism” made individuals feel targeted as “potential terrorists.”

39

Likewise, “at-

risk community” strategies risk similar blowback, especially when targeted at faith communities. Such

programming, like the New York Police Department’s “Muslim Surveillance and Mapping Program,” can

result in discriminatory profiling that ultimately alienates members of the communities they are

ostensibly intended to engage cooperatively and who are best-positioned to detect and potentially

intervene in actual cases of violent extremism.

40

35

For a helpful and comprehensive review of CVE program studies prior to 2017, see: Gielen, Amy-Jane. "Countering Violent

Extremism: A Realist Review for Assessing What Works, for Whom, in What Circumstances, and How?" Terrorism and Political

Violence (2017): 1-19.

36

IE those short of legal or security measures such as arrests, freezing of finances, police surveillance, etc.

37

Usually measured in terms of beneficiaries reached, program retention/completion rates, and other metrics that indicate

whether the program operates as designed and reaches the intended participants. Some programs do include participant

feedback (either qualitative in the form of focus groups, or quantitative, usually in the form of evaluation surveys), but this

feedback usually revolves around similar measures which Gielen (2017) describes as “process evaluation.”

38

Ibid (p. 6)

39

Thomas, Paul. "Failed and friendless: the UK's ‘Preventing Violent Extremism’ programme." The British Journal of Politics and

International Relations 12.3 (2010): 442-458.

40

Schanzer, David H., et al. The challenge and promise of using community policing strategies to prevent violent extremism: A

call for community partnerships with law enforcement to enhance public safety. Durham: Triangle Center on Terrorism and

Homeland Security, 2016.

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| 11

A second major challenge to studying P/CVE program impact is with respect to program design and

implementation itself: at what level of aggregation should programming be targeted? And which stage of

radicalization or VEO involvement should be addressed by the program? These issues are examined

further in the next section of this report, with the case of Bangladesh in mind. A third major

challenge is in measurement of program effects: even if a P/CVE program is correctly implemented as

designed and reaches its target audience, how would we know whether participants receiving

“treatment” are actually being affected by it in ways consistent with the program’s policy goals?

Outcomes of interest (which include concepts such as radicalization and the risk of participating in

violent extremism/violent extremist groups, or violent extremism antecedent attitudes/behaviors

41

) are

rare and difficult to detect in the form of observable behaviors. Attitudinal measures (i.e. surveys) must

contend with social desirability bias, which can present challenges when using them for measuring

program effects.

42

In summary, the paucity of convincing evidence for the efficacy of P/CVE programs is not due to

incompetence or carelessness on the part of researchers and practitioners, nor is it due to poorly-

designed programming. Rather, it is due to these aforementioned methodological challenges and the

“needle-in-the-haystack” nature of the substantive problem itself. Despite these challenges, some notably

well-designed studies have been helpful in clarifying areas where P/CVE programming might be most

promising. Work by Aldrich (2012; 2014) studying USAID radio programs in Mali, Chad and Nigeria, for

example, has provided quasi-experimental evidence that CVE messaging can alter norms of civic

participation and behavior among individuals in ways suggesting a greater willingness to work with the

West in combatting terrorism.

43

An evaluation by Williams et al. (2016) has provided evidence that community-focused secondary

prevention programs may be effective when targeted towards peer “gatekeepers.”

44

Given the difficulties in implementing and assessing efficacy of programs that attempt to identify at-risk

individuals and/or intervene in cases further down the radicalization pathway, a more promising

approach for P/CVE programming is likely in the area of prevention. Prevention can be achieved through

counter-communication, resilience-building, and/or the provision of support to key networks and actors

who are likely most efficacious in prevention efforts.

45

A useful taxonomy of P/CVE prevention

41

Attitudes and behaviors that are often associated with those who later go on to participate in violent extremist groups

and/or acts of political violence. These attitudes may be context-dependent in their specific manifestation, but often have

common themes which include (but are not limited to) out-group disgust (i.e. racism, homophobia, anti-Semitism, etc.),

misogyny, authoritarian personalities and views, a need for closure, or black-and-white worldviews. Associated behaviors might

include, for example, hate speech, violence against members of the out-group (or the advocacy thereof), intolerance for

differing beliefs/worldviews, or risk-taking behavior that is indicative of fatalism. It is important to note that violent extremism

antecedent attitudes/behaviors are not ubiquitous among those involved in violent extremism, nor are those who exhibit such

attitudes/behaviors certain to radicalize and pursue violence. For a further discussion, see: Gambetta, Diego, and Steffen

Hertog. Engineers of Jihad: The curious connection between violent extremism and education. Princeton University Press, 2017.

42

This problem is discussed at length by Horgan & Braddock (2010) in evaluating “de-radicalization” programs, which are often

implemented in such a way that incentivizes participants to exhibit reformed attitudes and behaviors, often to avoid punishment

or secure better prison conditions, early release, etc.; see” Horgan, John, and Kurt Braddock. "Rehabilitating the terrorists?

Challenges in assessing the effectiveness of de-radicalization programs." Terrorism and Political Violence 22.2 (2010): 267-291.

43

Aldrich, Daniel P. "Radio as the voice of god: Peace and tolerance radio programming’s impact on norms." Perspectives on

Terrorism 6.6 (2012): 34-60; Aldrich, Daniel P. "First steps towards hearts and minds? USAID's countering violent extremism

policies in Africa." Terrorism and Political Violence 26.3 (2014): 523-546

44

Williams, Michael J., John G. Horgan, and William P. Evans. "The critical role of friends in networks for countering violent

extremism: toward a theory of vicarious help-seeking." Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 8.1 (2016): 45-65.

45

Harris-Hogan, Shandon, Kate Barrelle, and Andrew Zammit. "What is countering violent extremism? Exploring CVE policy

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| 12

programs is inspired by public health models, and separates such efforts into those deemed primary

prevention (aimed at decreasing “new cases,” or incidence of radicalized individuals), secondary

prevention (aimed at decreasing the prevalence of radicalized beliefs within a network and dissuading

radicalized individuals from going on to potentially engage in violent extremism), and tertiary prevention

(aimed at convincing those already engaged in violent extremism to disengage and de-radicalize).

46

Notably, this model of radicalization remains agnostic to the potential actions taken by radicalized

persons (which are not necessarily violent). Moreover, not all of those who commit acts of violence on

behalf of VEOs have been radicalized; however, for non-conflict zones (and certainly the case of

Bangladesh), radicalization is generally prerequisite to involvement in (and violent acts on behalf of)

VEOs.

Regarding this taxonomy of prevention-focused P/CVE programs, tertiary efforts pose the greatest

difficulty for targeting and for evaluation, due to the methodological reasons discussed above. While

“soft” programming that targets individuals already involved in violent extremism likely has an important

place in policymakers’ repertoire of P/CVE tools, such efforts in practice are usually targeted to those

who have already had contact with state security efforts (i.e., prisoners), and thus fail to reach those

currently engaged in violent extremist activities for the obvious reason that such individuals are doing so

clandestinely or are not otherwise reachable.

Primary and secondary prevention efforts form the bulk of prevention-focused P/CVE programming

attempted thus far. The sparse evidence available from past evaluation paints a mixed picture regarding

the efficacy of primary prevention P/CVE efforts, i.e., those designed to “inoculate” a population against

extremist ideology through programs that address root causes of radicalization. These primary

prevention programs are usually attempted through direct counter-messaging efforts, or indirectly by

addressing psycho-sociological causes of radicalization, by imbuing critical thinking skills, or by raising

awareness among families and support services. For example, several studies have more or less

concurred that interventions aiming to address inter-group prejudice or extremism can be effective in

changing norms of behavior, though not necessarily in changing the underlying attitudes and beliefs of

individuals.

47

Such findings suggest that prevention-focused P/CVE programs designed to persuade those

already holding violent extremist antecedent attitudes, or who may sympathize with violent extremist

groups, are likely to be ineffective, particularly if the program is short term and/or of low duration.

Unlike efforts to change attitudes and beliefs, relatively well-documented findings are available to suggest

that primary P/CVE interventions can change behavioral norms in areas substantively related to violent

extremism. This evidence comes from evaluations of programs designed to combat racism, gender

violence, and school bullying (among others).

48

The hypothesized mechanism behind such programming

and practice in Australia." Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 8.1 (2016): 6-24

46

Ibid.

47

Examples are varied, and include studies of interventions focusing directly on attitudes towards violent extremism (Aldrich

2012; 2014), as well as those meant to address antecedent behaviors such as out-group prejudice, and violence against women

(see: Scacco, Alexandra, and Shana S. Warren. "Can social contact reduce prejudice and discrimination? Evidence from a field

experiment in Nigeria." American Political Science Review (2018): 1-24; Coker, Ann L., et al. "Evaluation of Green Dot: An active

bystander intervention to reduce sexual violence on college campuses." Violence against Women 17.6 (2011): 777-796.) Doubts

about the efficacy of persuasion attempts via short and medium-term programming are apparent in substantive foci beyond CVE

and antecedent behaviors as well; regarding attitudes on dating violence, for example, Storer et al. (2016)’s review of 15

programs found mixed evidence that bystander intervention programming reduced rape myth acceptance among men despite

being effective at changing behavioral norms.

48

See, for example, Coker, Ann L., et al. "Evaluation of Green Dot: An active bystander intervention to reduce sexual violence

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| 13

is that, by publicizing and reinforcing a norm against some socially undesirable behavior, it both decreases the

likelihood of its expression among those holding attitudes that might lead them to express it, and empowers

others who hold attitudes opposed to the behavior to further reinforce the norm against it. Applying such

findings to primary prevention-focused P/CVE programs suggests that the most promising approaches

might focus on changing the social milieu of acceptable behaviors regarding violent extremism

antecedent behaviors, rather than attempting to directly change individual-level attitudes.

An obvious impediment to primary prevention-focused P/CVE efforts is one of program scale, given that

the potential social reservoir for “at-risk” individuals covers a broad swath of the population, even when

accounting for some regularities among the eventual perpetrators of violent extremist acts.

49

Moreover,

while such efforts may be feasible in contexts with available resources to devote to wide-spread

implementation of such programming, the very correlates that put a society at high risk of violent

extremism- challenges such as unequal development and income inequality, political polarization, social

cleavages, distrust in the criminal justice system, and strained social support services- also leave it

unequipped to implement such measures at scale. Take the public health model of prevention, for

example: deploying such efforts in a resource-limited context would be like implementing a hand-

washing campaign in a society that lacks clean water infrastructure and soap.

Given the targeting and methodological impediments to tertiary prevention CVE programs, and the

practical impediments to primary prevention, secondary prevention CVE programs are likely to offer the

most cost-effective and potentially fruitful approach to addressing violent extremism in a context such as

Bangladesh. Such efforts attempt to prevent further radicalization of individuals holding violent

extremism antecedent attitudes, while empowering individuals within the networks of those at-risk to

act upon witnessing violent extremism antecedent behaviors and therefore reduce their expression and

diffusion. Specifically, an application of the BIT model for secondary prevention might offer a promising

and practical method for CVE in a context such as Bangladesh. The next section of this report details

the BIT model and its adaptation for secondary P/CVE purposes in Bangladesh.

4. THEORY OF CHANGE

This evaluation considers a capacity-building secondary P/CVE strategy for creating social environments

hostile to violent extremism, focusing on promoting the social norm of “tolerance” through bystander

intervention training (BIT). Furthermore, the evaluation considers a BIT strategy focusing on “peer

gatekeepers,” both as the individuals delivering the training, and those receiving it. As discussed,

programs that attempt to target at-risk youth are usually of limited success because they require finding

the proverbial needle in the haystack. A more effective strategy, then, may be to change the permissive

social milieus in which hateful speech, harassment, and other antecedent behaviors of violent extremism

are left unchallenged, leaving an open path for escalation toward actual violence. The principal

investigators therefore proposed testing programs to change the social environments that may allow

on college campuses." Violence against Women 17.6 (2011): 777-796.)

49

It is well-known, for example, that most individuals who commit acts of terrorism are young males, with some evidence

suggesting that educated and middle-class males may be especially vulnerable, and even more so if they experience “significance

loss events.” However, even with slightly better specific demographic and psychological predictors- the observation in

Bangladesh, for example, that perpetrators tend to come from the educated middle class- the target population for primary

prevention CVE programming would be too vast to realistically and efficiently reach.

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| 14

violent extremism to grow, delivered by those whose identities or social positions among the target

audience would potentially facilitate said changes.

We ask:

1. What is the effect of a tolerance-focused bystander intervention training P/CVE program on

effective intervention to promote and protect norms and behaviors against P/CVE antecedent

attitudes and behaviors among those receiving it?

2. Are trained peer leaders more effective at delivering said bystander intervention training program

than traditional authority figures for the context?

We theorize that the tolerance BIT program will affect change through two pathways. First the program

will change norms within the subject pool to reject hate and be more tolerant of various outgroups,

such as Hindus, women, and Westerners. Second, the program will increase subjects’ capacities to take

pro-tolerance actions and make the subjects more effective as pro-tolerance interveners by training

them in effective social intervention techniques.

The first pathway in the theory of social change is through improving norms of tolerance. The use of the

term norm is unfortunately quite varied, referring sometimes to how the members of a group do behave

and other times to how such members should behave. The former type of norm, how members of a

group do behave, is called a descriptive norm and the latter type of norm, describing how members of

the group should behave, is called a prescriptive norm.

50

In theory individuals comply with norms because

failure to do so risks some form of social censure (for example embarrassment, reprimand and

exclusion). Psychologists frequently argue that individuals are often imperfectly informed about actual

norms due to limited opportunities for observation and cognitive shortcomings.

51

Thus, psychologists

are often more interested in perceived norms rather than actual norms. We follow that convention in

this report: when we use the term norms we are actually speaking of perceived norms. Most of our

analysis focuses on prescriptive norms, although we do not ignore descriptive norms entirely.

Norms are to be distinguished from what psychologists call attitudes but what economists might call

preferences. Attitudes/preferences are an individual taste for an activity. A person who engages in

tolerant behavior because they like pleasant social interactions or were born with an elevated sense of

empathy are indulging a preference for tolerance. Programs typically attempt to bring about social

change by changing perceived norms rather than attitudes/preferences because the latter are thought to

be harder to change than the former.

52

Compliance with perceived norms is undoubtedly aided by a

preference for the normative behavior but it is not necessary. Compliance with perceived norms

operates through a desire for social acceptance. For example, people may recycle even when they find it

50

Prentice, Deborah A. 2007. Norms, Prescriptive and Descriptive. Encyclopedia of Social Psychology, Roy F. Baumeister, and

Kathleen D. Vohs, Sage Publications, 1st edition.

51

Tankard Margaret E. and Elizabeth Levy Paluck. 2016. Norm Perception as a Vehicle for Social Change. Social Issues and Policy

Review. Vol. 10:1 181—211; Perkins, H. W. (2002). Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts

Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement, 14, 164–172 ; Perkins, H.W.,Meilman, P.W., Leichliter, J. S., Cashin, J. R., & Presley, C.

A. 1992). Misperceptions of the norms for the frequency of alcohol and other drug use on college campuses. Journal of American

College Health, 47(6), 253–25.

52

Tankard Margaret E. and Elizabeth Levy Paluck. 2016. Norm Perception as a Vehicle for Social Change. Social Issues and Policy

Review. Vol. 10:1 181—211

CONTRACT No. GS-10F-0033M / ORDER No. AID-OAA-M-13-00013 / DRG-LER I TASKING N058

USAID.GOV

OBIRODH Impact Evaluation: Road to Tolerance Youth Leadership Training Program in Bangladeshi Universities

| 15

inconvenient for fear of social sanction if they do not. Thus, changing perceived social norms can affect

broad social change even when underlying attitudes or preferences remain fixed.

53

Tankard and Paluck (2016) list three sources of information that can change perceived norms: the

behavior of salient individuals, descriptive information about the community and institutional signals.

They give the example of a hypothetical program to increase recycling in a community: “…a norm

change intervention may, for example, expose people to a popular peer who recycles, provide people

with information that most of their peers recycle, or advertise new recycling guidelines from an

important and trusted community institution.” (p. 183).

54

Recent research has indicated that changing individuals’ perceived norms can successfully produce

changes in individuals’ behavior and broader social change through these three channels. For example,

Paluck and Shepherd (2012)

55

and Paluck, Shepherd, and Aronow (2016)

56

report on an intervention

that reduced high-school bullying by changing perceived norms through the first channel mentioned

above: popular peers. Perkins and Craig (2006) employed the second channel, information about average

peer behavior, to reduce alcohol abuse in college.

57

Tankard and Paluck (2017) show how a Supreme

Court decision changed the norm on same-sex marriage via the third channel, i.e., a trusted community

institution, even when underlying attitudes on same sex marriage had not necessarily changed.

58

The BIT program studied in this report aimed to change perceived norms through the first channel, i.e.,

through statements/behavior of salient individuals (the trained facilitators). We tested the ability of two

sorts of salient individuals to convey the message of norms of tolerance: peer leaders and college

instructors.

We propose that effective intervention (i.e., the promotion and protection of desirable norms- in this

case norms of tolerance and norms against violence) requires individuals to have internalized the

prescriptive norms of tolerance, while also having both the competence and the confidence to publicly

defend those norms in the face of hateful speech or actions. An individual’s confidence and competence

to promote and defend prescriptive norms, in turn, is predicated on (1) the individual’s internalization of

those norms, and (2) the internalization of capacities (i.e., skills) necessary to safely promote and defend

the norms.

59

We expect both a tolerance-focused bystander intervention curriculum, coupled with a

53

Ibid

54

Ibid

55

Paluck, E. L., & Shepherd, H. (2012). The salience of social referents: A field experiment on collective norms and harassment

behavior in a school social network. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103, pp. 899–915.

56

Paluck, E. L., Shepherd, H., & Aronow, P. 2016. Changing climates of conflict: A social network driven experiment in 56

schools. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

57

Perkins, H. W., & Craig, D. W. (2006). A successful social norms campaign to reduce alcohol misuse among college student-

athletes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67(6), 880–889.

58

Tankard M.E., Paluck E.L. (2017). The Effect of a Supreme Court Decision Regarding Gay Marriage on Social Norms and

Personal Attitudes. Psychological Science. 28(9):1334-1344.

59

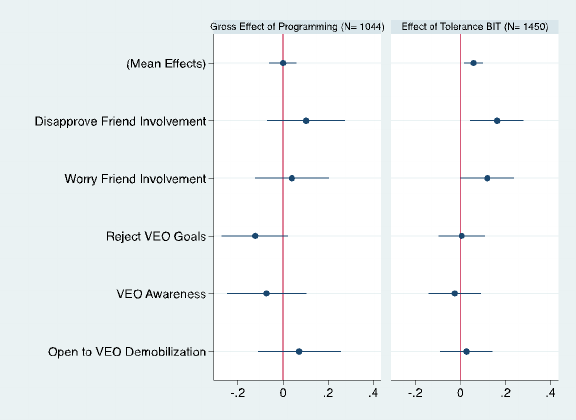

Note that the internalization of desirable (i.e. tolerant) norms is considered prerequisite to skill-building too. This reflects the