DOCUMENT RESUME

ED 243 358

HE 017 164

AUTHOR Danzig, Arnold B.

TITLE

Honors at the University of Maryland: A Status Report

on Programs for Talented Students.

PUB DATE

Aug 82

NOTE 61p.

PUB TYPE

Historical Materials (060) -- Reports

Descriptive

(141)

Reports

Research/Technical (143)

EDRS PRICE

MF°1/PC03 Plus Postage.

DESCRIPTORS

*Academically Gifted; *College Curriculum; Counselor

Attitudes; *Departments; Educational Benefits;

Educational History; Higher Education; *Honors

Curriculum; Program Descriptions;, *State

Universities; Student Attitudes; Student

Characteristics; Teacher Attitudes

IDENTIFIERS

*University of Maryland College Park

ABSTRACT

The history and current status of honors programs at

Ai.;: University of Maryland, College Park, are discussed, with some

reference to special recent programming for gifted students. The

following historical developments are covered: honors programs at

Columbia College in the early 1900s, the idea of honors as a separate

upper division program at Swarthmore College; and St. John's

College's Great Books curriculum, which has similarities with honors

programs. Honors programs were established at the University of

Maryland during the 1950s and 1960s, and the earliest programs were

conducted by departments. The environment during President Elkins'

administration was av, impetus for the honors program. The current

impact of the University of Maryland's honors-programs on the

university and the general population was evaluated, based on a

survey of public and private high school counselors, honors program

faculty, students in departmental honors and, general honors programs,

and students not in an honors program. Survey results ,for each of

these groups are presented in detail, and an ethnographic analysis of

the general honors program is presented. In addition to examining

characteristics of the general honors program and students enrolled'

in the program, admissions data for academically talented students

are considered. (SW)

***********************************************************************

Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made

from the original document.,

a.

......... 4.4.44.4.4.4.4.4.4.***********************************************

t

CO

LC\

PrN

Pr1

LU

HONORS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND:

A STATUS REPORT ON PROGRAMS FOR TALENTED STUDENTS

by

Arnold B.

Danzig

Research Associate

Center for Educational Research and

University of Maryland

Baltimore County

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS

MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY

rJ

TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC).

August ,

1982

Development

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION

NATIONA INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION

EDUCATI AL RESOURCES INFORMATION

CENTER (ERIC/

s document

trot;

been repronwed as

received

Iron, the person or organrahon

orlfpuiilti n ft 1

Minor changes have been matte to improve

retutadto,t,onolmhty.

.Po.ntsoh,nworoprNmsstatedinmsdo.

meat do no: necessanlyter7r1,1,11(lffiClaiNIE

pOSIIIMIMMflICY

COMMITMENT TO THE GIFTED AND Ti.LENTED

IN AMERICAN HIGHER EDUCATION

The American commitment

to the gifted and talented student has

followed,

at best, an uneven road.

In general, educators and policy makers

have advocated

an egalitarian or democratic approach

to education.

However, the democratic

ideal leaves unanswered the

question "Should equality mean 'equality

of oppor-

tunity' or 'equality of outcome'?"

Gardner (1961) suggests that the dilemma

raised is whether to

encourage individual performance to the end that each

person becomes all thathe or she is able

or to restrain individual performance

so that differences in results

may be reduced.

This dilemma is addressed by looking

at programs for gifted and talented

students and, in particular, by

looking at Honors programs.

According to

C.G. Austin, an Honors

program is a "planned set of arrangements

to serve the

needs of talented students

more adequately than if the matter

were left entirely

to the initiative of interested persons"

(Austin, 1975).

This modern defIni-

tion belies the controversy

which has surrounded programs created

especially

for gifted students.

Proponents of Honors approaches wish

to encourage individual performance.

The stated goal is not

to create an elite group with special

privileges and

opportunities, a creme de la

creme.

Rather, it is to prevent the

cream from

going sour.

They argue that what is right about

the Honors approach

-- the

encouragement and support, the potential

for intellectual and emotional growth

is right for all students.

Providing environments that facilitate

such growth

may vary, however, according to the individual

and his or her ability.

Opponents argue that providing special

environments for those already

ahead of their peers fosters elitism.

Denying some children the opportunity

to participate in certain educational

experiences is not seen as the

way to

improve school performances.

Children learn frOm the differences between

them.

as much as from the similarities; homogeneous

grouping based on cognitive and

non-cognitive characteristics ignores

this possibility.

Special programs should

be developed with all students

in mind.

The purpose of this report is

not to arbitrate this argument.

Rather,

ill look at the history and

development of.programs for the gifted

student

vith special reference

to the developMent of university Honors

programs.

This

followed by a discussion of

the history of Honors at the University

of Mary-

land and finally by

an analysis of Honors programs as they exist

at the Univer-

sity today.

3

From the outset, the

\

anted here is that fostering

special

privilege and elite status

rereut issue than providing

educational

environments which stimulate

growth.

Ralph Turner's (14'60) dis-

cussion of 'Contest' and isponno

ability suggests a view that the

accepted

mode of upward mobility

shapes th

ce of particular schools programs:

The governing objective

of contest mobility is

to give elite

status to those who earr .1!:, while

the goal of sponsored

mo-

bility is to make the be:,._

use of the talents in society by

sorting each person int.-

is proper niche.

In different

societies the conditiol::

.f competitive struggle

may reward

quite different attributes...

(p. 857)

In other words, the prevailing

norm of upward mobility influences what

is

valued/valuable in the school

experience.

By itself, the content of

an

educational setting does

not determine movement through the

stratification

system.

Gardner (1961) makes another

point relevant to the discussion

when ne

suggests that neither equal opportunity

nor equal outcome, when taken alone,

serves the democratic ideal.

Rather, the combination of the

two philosophi-

cal perspectives meets the

needs of society:

There is evidence, in short, that

the critical lines of

tension in our society

are between "emphasis on individual

performance" and "restraints

on individual performance."

This tension will

never be resolved and "never should be

resolved" (our emphasis)...

...No democracy can give itself

over to extreme emphasis

on individual performance and still remain

a democracy

or to extremeequalitarianismand still

retain its vitality

(28-9).

n1-

tin !r

As a result, the nation

alternates between the two

patterns or must find a

way of combining equalitarianism with

the pursuit of individual excellence.

University Honors

programs may be an example of this latter

approach.

Defining Honors Programs

Earlier, a brief quote from

C. Grey Austin was given

to describe Honors

programs.

Austin, University Honors

Director at Ohio State University,

sug-

gests that it

is necessary for an educational

institution to meet the educa-

tional and intellectual needs

of the brightest and ablest

students in specific

3-

programs rather than in a haphazard

or by chance manner.

His objectives for

such programs

are to:

1.

Identify students whose ability

and motivation are so high that

;their academic needs would

not be adequately met by existing

programs;

2.

Provide academic opportunities

of such caliber that the students

thus identified are challenged

to perform at the highest level of

excellence of which they

are capable and through which they

may

become independent learners;

3.

Establish an environment

that will encourage the aspirations

of

and the achievements by

these students and that will foster

in

them dignity, self-esteem, and

a sense of their potentials;, and

4.

Derive from the program benefits

for the wider academic community

such as focusing attention

on quality education and a concept of

excellence, giving faculty members

the psychic reward that derives

from working with gifted

studentsand attracting to the

campus

scholars and speakers who would

not otherwise be there (Austin,

1975, 161-2).

Special programs, by definition,

allow changes in existing

programs.

The existence of honors

sections may go hand in hand

with the development of

supplemental courses for students

at the other end of the continuum.

For

example, both honors and

compensatory programs allow students

to work-at

levels suited to their abilities.

Rather than associating Honors with

elitism, Honors can be

seen as a way of providing opportunities

for students

.t

in the highest ranges of ability

to get the most out of their educational

experiences.

Ultimately, the view presented

in this report is that Honors

programs

are in the interest of the wider

academic community and not

a mechanism to

provide special advantages

for a future elite

group.

By providing an image

of excellence and by

stimulating the brightest students

to their best efforts,

the University and society

benefit.

Understanding the historical

development of Honors

programs provides the

reader with the origin of

this interpretation.

In later sections the specific

history of honors at the

University of Maryland and

a current status report

will be presented.

-4-

A Short History of Honors

as it Developed at American Collees

American colleges in the

seventeenth and eighteenth

centuries provided

a

'liberal education' (Butts

and Cremin, 1953).

This implied a broadly

general

rather than narrowly

specialized course of study

leading to the 'well-rounded'

development of the individual.

In addition to a breadth of

study, liberal

education was associated

with intellectual rather than

utilitarian pursuits

and education

was seen as an end to itself

rather than a means to

some end.

By the time of the American

Revolution, nine colleges had

been established

in Colonial America.

2

And according to Butts and

Cremin, while the motives

for establishing

seven of them had been religious

or with a sectarian bent, two

showed signs of growing

practical and scientific

interest (1953, 81).

Cremin

(1970) points out

an expansion of the mathematical

and scientific

programs

was accompanied by enlargement

in the course in moral

philosophy and the re-

entry of certain traditional

professional studies into the

college curriculum.

During the nineteenth

century, the traditional liberal

arts curriculum

came under attack.

The classical/literacy

curriculum was perceived

as more

suited to the needs of

an aristocracy than the practical

needs of a country

rapidly expanding (Brubacher,

1966).

The natural sciences

came to be increas-

ingly viewed as a vital

subject of study and the

establishment of technical

institutes (RPI, MIT) bears

witness to this fact.

The relationship of Honors

programs to curricular reform

can be interpreted

in two ways.

First, Honors may be

seen as a retrogressive effort

to maintain

the classical curriculum

of the liberal education

targeted for a select portion

of the population.

Second, Honors programs

may he perceivedl'as a way of

pro-

viding additional opportunities

for those wishing to enrich

their college

experience by providing

alternatives to the prescribed

curriculum.

In this

sense, Honors may be interpreted

as being in the spirit of democratic

reform

because it provided

alternatives to the college

curriculum.

The perception of Honors

in one way or the other

influenced the direction

and implementation of

programs.

When Honors was perceived

as providing greater

alternatives it was

more readily accepted than when it

was seen as providing

opportunities for a selected

few.

From 1872 to 1897 Harvard

president Charles Eliot instituted

an expanded

elective system in which

students had greater alternatives

available to them.

6

-5-

Joseph Cohen suggests that the expanded elective

system was seen "as a

liberating reform in keeping with nineteelith-century

democracy" (1966, 13).

And according to R. Freeman Butts, the goal of

the elective system was to

meet the demands of students and the community for

a useful education.

The

changes were perceived. as reforms in higher

education to meet the demands of

a modernizing society (Butts, 1973).

In 1903 Harvard Professor A. Lawrence Lowell

attempted to establish an

Honors College.

In 1909 Yale President Arthur Twining Hadley

proposed an

Honors plan.

In spite of providing curriculum alternatives, neither

plan was

enacted.

The question of why Honors

was not seen in the same way as an expanded

elective system is answered by referring the

reader to an earlier point which

suggested that the content of an educational

environment is often secondary to

the perception of its importance.

In this case, Honors may have been perceived

as providing special advantages aside from the particular

content of course

knowlec'ge and rejected as undemocratic.

Columbia College

A more detailed example of the Honors approach

is found by looking at

Columbia College, New York (Buehler, 1954).

In 1909 a three-year program of

supplemental reading followed by

an oral examination was established.

In 1912,

a second program was started which included weekly conferences and

student dis-

putations.

To the extent that these programs provided enriched

environments

aimed at improved student performances, they

are considered, at least implicitly,

Honors programs

The first explicit program of Honors

at Columbia was the "General Honors"

program established in 1920 under the direction of its

proposer, English pro-

fessor John Erskine.

It called for the "systematic reading of masterpieces

in poetry, history, philosophy and science

and individual work in some chosen

field of scholarship under the direction

of a designated Honors Director"

(Buehler, 1954, 56).

At about the same time, Columbia also introduced

a gen-

eral education course required for all freshmen,

known as 'Contemporary

Civilization."

Taken together, General Honors and the Contemporary Civiliza-

tion may he indicative of a commitment

on the part of the College to inter-

departmental collaboration (Buehler, 1954, 56).

-6-

General Honors at Columbia

emphasized small group study,

informality, and

outside reading.

Sections were composed of about

fifteen students and used

a

discussion/exchange of ideas

approach.

Two faculty members, of differing

approaches, were chosen

to preside over weekly meetings

held at night with

no

specific time limit.

The goal of General Honors

and CC were for the student

to gain some "real

understanding" of

some of the great literary masterpieces.

ErSkine's approach

was to suggest that these works

could be enjoyed; that indeed

they existed primarily

to be enjoyed; that they

were storehouses of rich

experience that was meant to be

shared (Buehler, 164).

Erskine argued that

masterpieces had first been popular

in a particular period

of time.

The people who had first read

these books/seen these plays

had not

waited for scholarly

lectures in order to enjoy them.

In so stating, Erskine

gave voifle to the view that excitement

and vitality

have an educational importance.

Erskine suggested that it

was the young teach-

ers who made General Honors possible

for they gave life and

enthusiasm to the

3

great works.

During the 1920's, Columbia

continued its efforts to

meet the individual

needs of students.

One of the results of this

was the instittl/tion of a system

of electives whereby

a student could plan an individual

course of study.

One

of the byproducts of the

elective system was a less

competitive atmosphere

since student programs could

be more individually tailored.

In 1928, the General Honors

program at Columbia was dropped.

This may

have been because of the

perception that General Honors

ran contrary to the

less competitive atmosphere

that was developing.

However, the dismantling of

General Honors should

not be associated with a rejection

of the ideas that

Honors represented, namely

small classes/lively debate and

discussion/relating

classical to the here and

now/humanistic studies.

Rather, it represented

a

rejection of the idea that

these pursuits deserve special

recognition and

honorific titles for the student.

For it was hoped that

a student would enroll

in what later (1932) became

the "Colloquium on Great Books"

because of interest

in the course content and

procedures and not for some special

honors degree or

prestige (Buehler, 122).

-7-

Swarthmore College

The beginning of the

modern honors approach

is usually -associated

with

Swarthmore College and

the Honors program

developed there under

the direction

of Swarthmore

President, Frank

Aydelotte.

Aydelotte came to Swarthmore

in 1921,

at a time when the

college was more known

for its sports

program than its

academic programs.

Aydelotte, a former

Rhodes Scholar,

came to Swarthmore at

a

time when the College

was receptive to

movement towards academic

excellence

(Bhatia and Painter,

3).

During his studies

at Oxford, Aydelotte

was undoubtedly introduced

to the

pass /Honors approach.

Studies and examinations

at English universities

were

separated into two

groups, the pass degree and

the Honors degree.

Students

undertaking the former

took a less demanding

and less specialized

course of

study/examinations than

those pursuing Honors.

The requirements for

an Honors

degree were

more specialized and required

intensive study in

one or two related

fields to be followed

by a rigorous

set of examinations.

It is this approach

that served

as the model for Honors

at Swarthmore.

Aydelotte's inaugural

address as President

of Swarthmore explains

his

thinking about Honors:

I do not believe that

we should deny to the

average, or

below average student,

the benefit of

a college education.

He needs this training,

and we need his

humanizing presence

in the colleges, but

we should not allow him

to hold back

his more brilliant

companions from doing that

quality of

work which will in

the end justify the

time and money we

spend in education

(Swarthmore College

Faculty, 1941).

And the program that

Aydelotte developed

emphasized the depth of

understanding

rather than an accumulation

of generalized

knowledge.

At the beginning of

the junior year students

were selected to enter

a

special program,

separate from the normal

college courses.

Two subjects,

instead of the normal

four to six,

were studied each semester.

The subjects

were to be related in such

a way that a.student would

concentrate efforts in

two or three contiguous

areas.

For each subject, the

student attended weekly

meetings with three

to six

other students and

an instructor.

This weekly "seminar"

was informal and often

met

he instructor's home

or at some equally informal

setting.

In each subject,

a student was required

to take written and oral

examina-

tions, prepared and

administered by examiners

outside of the College.

-8-

Examinations were used

to determine what class

of Honors (highest,

high,

honors, or no honors)

the student received.

According to Aydelotte

(1941), the Honors

program that developed

was partly

the result of

planning and partly

a matter of expediency.

juniors and seniors

were selected so that

prerequisites could be

completed and performance

capa-

bilities could be

judged.

Informal seminars

with three to six

students and

one faculty member

were the result of

an overworked faculty

not anxious or will-

ing to prepare

nets lectures.

(The seminar format

has been maintained

through

the present with

the rationale that

small groups, informally

convened, lead

to more meaningful

participation.)

Taking subjects in

related areas

was based

on the idea that

concentration of pursuit

better served the

needs of able

students.

External examiners freed

the faculty from

the dual role of

teacher and evaluator

and fostered

an advocacy relationship.

Honors at Swarthmore

has continued

to the present without

major change.

And although the

approach has attracted

a great deal of attention

it has not

been widely emulated.

According to Joseph

Cohen:

Because of the

inescapably elitist

nature of his British

model, the restriction

to the upper division,

and the

atypicality of Swarthmore

itself, the public

sector of

American colleges and

universities remained

in the end

largely unaffected

by his program (Cohen,

10-11).

Further, it is

suggested that Honors,

as defined at Swarthmore,

ignored the

different patterns

of social

ascent through education

characteristic of

England and the

United States.

As a result the idea

of Honors as

a separate

upper division

program had limited impact

on American higher

education.

St. John's College,

Annapolis, Maryland

Though not typically

thought of as

an honors approach, the

Great Books

curriculum at St. John's

College is included

in this section

because its

rationale.has commonalities

with honors, i.e.,

the training of

intellect and

the attempt

to meet a perceived

decline in standards

and intellectual

performance.

In 1937, while

President of the

University of Chicago,

Robert Hutchins,

and others, persuaded

the faculty at St.

John's College

to adopt a curriculum

based on the

greatest books of all

time.

The 'greatness' of

a hook was judged

-9--

by its status as

a classic, a book relevant to every

age.

The curriculum con-

sisted, in part, of critical

reading of the one hundred

greatest books of all

time.

Students also studied mathematics,

laboratory science, music, and

1;!7

languages, and attended weekly

lectures (Morris, 1961).

The curriculum was

prescribed and each student

went through the same cours,.e. of study.

The idea behind the Great Books

curriculum was that if someone could

master the greatest books of all

time, then certainly this

person could find

his/her way in the

present era, that "...a thorough saturation

in the greatest

thinking of the greatest

minds is the way to train the intellect"

(Morris, 350).

Science labs attempted to

recreate the important experiments of the

great minds

of science:

Galileo, Kepler, Newton, et al.

By "actually imitat!ng the

greatest

intellects of our scientific

past, the student begins to

sense the inner workings

of those intellects, in

a sense sharing in their genius for experimental

design"

(Morris, 351).

By rubbing elbows with genius, it

was hoped that some might rub

off.

Although the Great Books curriculum

remains at St. John's today, it has

never really spread to other colleges (and

perhaps that was not the intention

of those who founded it).

The exclusion of new knowledge

becomes increasingly

difficult in light of the 'future

shock' of a world changing

rapidly.

The lack

of alternative paths for

students of different inclinations

also seems par-

ticularly constraining.

However, the idea of liberal studies,

of intellectual

discipline"; has a large following

in Honors programs across the

country.

In

this sense, the Great Books and

Honors may be seen as having

a common objective,

that is, to uplift the thinking of

men and women in their dreams, desires, and

abilities to carry them out.

Summary

To sum up this first section

on the history of Honors, a number of points

are made in the discussion.

From the history of Columbia, Honors

is seen as

emphasizing interdepartmental

collaboration with the small

group study and lively

debate format.

Excitement and vitality are seen

as the life force for curricular

development.

However, the idea of Honors

as a separate or exclusive experience

is rejected.

From the Swarthmore experience, the

notion of a separate two-year Honors

track for a select portion of

students is introduced.

Honors is seen as informal

1.1

-10-

discussion with small

groups participating in lively

debate.

Intellectual

growth occurs as

a result of association

with one's gifted

peers and concen-

tration of effort.

However, the perception

of exclusivity

prevented the

Swarthmore approach from

being widely emulated

at other colleges.

From the discussion

of St. John's,

another model is

presented which

stresses the importance of

'liberal studies' and

encourages excellence from

the

total college population.

Seminars, discussions,

lectures and independent

think-

ing are intended

to lead to the educated

citizen in the democratic

society.

How-

ever, the reliance

on the great books of the

past makes it a model

that is not

easily adapted to

a changing present.

The discussion also

introduces the debate

between proponents of

views

favoring special

environments for

very able students and those

who reject this

as elitist and

undemocratic.

The suggestion is

made that the two

views are not

mutually exclusive

and that both

are part of the healthy

growth of the nation.

Another point that is

suggested by the discussiOn

is that rather than

serving elitist ends,

Honors opened

up the curriculum.

In this sense Honors

served as a

democratizing force

at colleges and universities

and curricular

changes enacted in

Honors programs filtered

to the rest of the

population.

Finally, the rationale

of the modern

Honors approach is

presented in

the views of C.G.

Austin.

It is proposed that

Honors benefit

more than just

a select group of

participants.

The image of excellence

that Honors

encourages

provides a model for

all students.

Faculty derive psychic

rewards from being

able to work with

groups of very able students.

The campus atmosphere

is

enlivened because

scholars who might

otherwise go elsewhere

are attracted to

the campus.

In this way honors

is seen as benefiting

the whole university.

In the next section,

the particular growth

of Honors at MCP

is presented.

The Effort to Promote

Excellence

During the 1940's,

research on the gifted

child included the

study of

what happens

as the child grows older.

For example, L.

Terman and M. Oden

did a twenty-five

year followup cf Terman's

work at Stanford (The

Gifted Child

Grows Up, 1947) which

included discussion of

college-age youth.

12

According to Tannenbaum (1958) after World War II there

was an increased

interest in programs for the gifted student because of. the

Cold War demand for

scientific and-technological leadership.

Another impetus for programs aimed at able youth

came as a result of the

Russian launching of Sputnik.

The notion that the U.S. was first technologically

ran contrary to die reality of Russia's ability to launch the first unmanned

satellite.

The Harvard Report of 1945 suggested that the schools in the

U.S. were

Jim...I at a "somewhat colorless.

mean, too fast for the slow, too slow for the

fast" (Tannenbaum, 36-37).

One implication is that schools must meet the needs

of the ablest students.

The founding of the Merit Scholarship Program in 1955 is

indicative of the

growing interest in promoting and rewarding excellence

at the college level.

The National Merit Scholarship Corporation conducted

an annual competition among

U.S. citizens enrolled in secondary schools.

Students who ranked in the very

top of the academic scale were identified by taking a special examination (in

recent years this has been the PSAT and SAT).

Award winners were given special

recognition and sometimes financial assistance

to help them through college.

Such recognition must have supported efforts

to provide special programs for

these students once they arrived at college.

The Inter-University Committee on the Superior Student (ICSS)

The ICSS was set up when a grant was awarded by the Rockefeller Foundation

to the University of Colorado to. expand its Honors program.

The University had

established an Honors Program similar to the Columbia model which

consisted of

small classes with extra readings and group discussions.

The Rockefeller Foun-

Otion grant was intended for the

purpose of expanding the Colorado Program and

for the Director of Honors, Dr. Joseph Cohen,

to visit other schools and

organizations in preparation for a national conference

on Honors to be held

the following year.

A second grant from the Carnegie Foundation provided for

vet another conference that year which established the ICSS

as a national coor-

dinating body (Rhatia and Painter, 4).

The ICSS served from 1957 to 1965

as a clearinghouse for information and

acted to modify and disseminate information

about Honors.

The idea behind the

13

-12-

ICSS type of Honors

was that it should stimulate the

institution toward

quality and therefore benefit

every member of the community.

According to its

founder, Joseph Cohen:

The greatest benefit

of the ICSS type of honors

is that it

can stimulate towards quality

every type of institution of

higher learning.

It.is not an elitist

system (emphasis

added), but one that

aims at raising the standards

of

students and teachers

-- in professional as well as liberal

arts institutions

-- by providing models to emulate and

by

increasing motivation.

(Cohen, 44-45).

Thus, Honors

moves the university towards

excellence by providing

a standard

and standard bearers for

an image of excellence to which

all can aspire.

The impact of ICSS

on colleges and universities around

the country is

difficult to determine.

However, one criterion of

success may be the pro-

liferation of Honors

programs around the country during

its nine years in

existence.

Its ending should not be

interpreted as a rejection of

honors,

but rather to the

success that the Foundation seed

money had in promoting

honors around the

country.

ICSS was succeeded by the

National Collegiate

Honor Council,

on the assumption that the colleges

and universities could

themselves carry the

movement forward (Bhatia and

Painter, 5).

The NCHC

remains in existence today

with heidquarters at the

University of Maryland

College Park.

Honors at the University

of Maryland

During the 1950's and 1960's,

Honors programs at the University

of

Maryland were created

where none had existed while

existing programs were

expanded.

The pressures to build

Honors that came from outside

the-Univer-

sity have been discussed

in the last section.

In order to complete the

pic-

ture it would be useful

to point to some of the forces

within the University

moving it towards Honors.

The earliest Honors

programs were conducted by the

departments.

During

the late 1950's, the

Mathematics Department started

an H6nors Program by

rerruiting able high school

seniors.

Dr. Leon Cohen, Chairman of

the depart-.

ment, sent letters to high

schools in Maryland and the

District of Columbia,

asking for the

names of students showing outstanding

abilities in mathematics

14

-13-

and who the high schools felt

wolild benefit from such

a progrnm..

In 1959,

a special one-day orientation

was arranged for a group of fifty high school

students identified by their schools

as outstanding and as interested in

attending the University of Maryland.

The purpose of Honors in mathematics

was to discover mathematically

gifted undergraduates and

to offer them the best education possible.

Fresh-

man candidates were located by recommendations

Of high school teachers and/or

student scores on placement

examinations.

By 1961 the Math Department had 95

students in Freshman Honors

courses.

What is perhaps most interesting,

besides the program, is the

response it

received from within and from

outside the university.

Letters in the Math

Department files show parents, relatives,

and friends recommending individuals

to the attention of the department.

High school teachers and administrators

wrote in not only to recommend students

but to congratulate the department

on

its program ("It is indeed gratifying

to see provision made for able math

students"

letter from vice principal of Maryland

high school).

Letters of

support from university President Elkins and

Chairman of the Board of Trustees

Louis Kaplan, coverage in the local

press (Baltimore Sun), lead to the

con-

clusion that the program received

a great deal of attention and moral

support.

Each department has its

own history.

The experience of the Mathematics

Department may be slightly atypical

in that students were recruited for

a

program that began in their freshman

year.

However, the idea of providing

enriched environments is

very similar to the Honors approaches described

earlier.

Even the idea of dealing with

freshmen and not upperclassmen has

much in common with the description

of Honors.at Columbia.

Perhaps the idea

of recruiting able freshmen.was

new at Maryland, as was the idea of Honors

seminars in non-liberal

arts :,Ibject matter.

In any case, Math Honors,

as

a four-semester enti4.7hd course structure for

freshmen and sophomores and

as a junior/senior departmental 'program,

still exists at UMCP today.

Excellence Under the Elkins Administration

. Wilson Homer Elkins was appointed president of the

University of Maryland

beginning in the fall of 1954.

Dr. Elkins, like Frank Avdelotte, had

been a

Rhodes Scholar.

The commitment to excellence that

brought him to Oxford and

was nurtured there is revealed in his efforts

at the university.

15

Dr. Elkins arrived

at the university at

a time when faculty salaries,

morale, and participation

were at a low ebb.

The university's reputation

had

been hurt by a Middle

States Association "Evaluation

Report" which had

recommended that the university's

accreditation be 'reconsidered'

in two

years' time.

Although this did not

place the university

on probation,' it

was not the expected

vote to renew accreditation

(or an indefinite future).

During his first

year as president, Dr. Elkins

was able to persuade the

Maryland Assembly

to approve almost $300,000

for a new library and

addition

to the hospital, and $200,000

for increased operating

expenFas.

Dr. Elkins' first efforts

were aimed at correcting

a number of glaring

errors at the University, namely

satisfying the Middle

States Association,

improving faculty salaries

and working conditions,

reducing faculty

turnover,

and "once internal

reforms at Maryland

were under way, the administration

and

faculty set out

on a sweeping program to

encourage excellence in their

students" (Callcott,

389).

Elkins encouraged excellence

at the university in many

ways, a large

part of which was the

attempt to generate academic

standards.

A major step in

this direction began

in the fall of 1958, when

the university enacted

an

Academic Probation Plan.

Students were required

to achieve minimum level of

achievement or face closer

supervision and finally

'dismissal.

A second step

in the effort for

higher standards

was the introduction of pre-college

summer

session for high school

graduates with less than

a C average.

Along with an

orientation, students

were required to pass two

academic courses in order

to

be admitted to the

freshman class.

Though by today's standards

these Might

seem reasonable enough, it

was no small job to create

a state institution

that provided quality

instruction while not excluding

taxpayers and taxpayers'

children.

The attempts to

nurture excellence on the

part of the Elkins administration

should not be interpreted

as an attempt to change the

priorities of the univer-

sity by channeling

large amounts of funds

to train an intellectual elite.

Rather, it was

seen that a university needed

to handle diversity and that

this could only be

accomplished if programs

were suited to individual talents

and abilities:

16

-J5-

Growth at the University of

Maryland has led to outcroppings

of genuine scholarship

at the very highest level of

academic

achieveme-.L.

But this University

must do more than simply

serve those who can qualify

as the intellectual elite.

It

must serve the enormously varied

tastes and capabilities, of

larger numbers of people

(Elkins, 1978:3).

This suggests that

programs for the gifted are part of

a larger need of

providing equal opportunities

for students with

a wide range of abilities.

Excellence meant meeting

the needs of all, while

providing opportunities

for the very able:

There is nothing

more precious than a gifted mind.

Our

colleges and universities

rise above the commonplace when

they make it possible

for the truly great thinkers

of our

time to nurture the

creative spirit of our youth.

This is

the educational

process at its finest (Wilson H. Elkins,

1978: cover page).

It is not suggested that

Dr. Elkins was the motivating

force behind the

development of Honors

at Maryland because that is

simply not the case.

Rather, the example he

set, and the moral and intellectual

support he gave,

provided a fertile environment

from which E-nors

was able to grow.

Growth of the General Honors

Program

The general development

of approaches and

programs aimed at nurturing

excellence have been discussed

in earlier sections of this

report.

At this

point, it is informative

to understand the pattern of

growth and development

of Honors at the University

of Maryland.

To anticipate the later

discussion, Honors

programs developed at the

University in order to

meet the needs of superior students

by providing a

more personally suited intellectual

experience.

As the University grew in

size, both the role of

the State University in society

and kinds of students

served there underwent

changes.

Honors programs were an

attempt. albeit on

a limited scale, to provide

some special attention to those with

the greatest

abilities.

In the early 1960's,

two committees of the University Senate

(The- General

r.

Committee on Educational Policy

and the Committee on Programs,

Curricula, and

Courses) held a joint meeting

to discuss, in general terms, the

provisions

for an Honors

program.

The University Senate

Minutes (1/31/61) points out that

many colleges and universities

in the United States "have

undertaken special

programs for more capable students

and the merit of these efforts

is widely

-16-

approved."

The Joint Committees

then issued a

statement outlining an

approach

towards Honors at the

University, which included

the following provisions.

(1)

Colleges, schools, and

departments of the University

are encouraged to develop

Honors and independent

studies

most adaptive to their

fields.

(2)

The chief aim of the

Honors and independent

studies is to

encourage and recognize superior

scholarship.

(3)

Honors and independent

study programs should

provide the

qualified student with

the scholarly freedom

to develop

initiative and responsibility

in the pursuit of

knowledge

on his part.

(4)

Students enrolled in the

Honors and independent

studies

programs enjoy certain

privileges with reference

to

class attendance, library

regulations, and other

similar

matters with regard to

which conventional

restrictions

are superfluous in the

case of scholarly and purposeful

students.

(5)

Successful completion of

the program should be

appropriately

recognized on the diploma

and the transcripts

of the

students' records.

The expectation of the

Committees was that discussion

would occur within the

various schools, departments,

and colleges, and that

suggestions and proposals

for specific

programs would be developed.

The idea of Honors,

as already stated,

was rather general.

Specifics

were to be determined by

those planning the

program.

But what does

seem

clear from the previous

discussions is that Honors

was seen as a way of

pro-

viding opportunities

to work at an enriched and/or

accelerated pace; giving

qualified students

certain privileges;

recognizing scholastic

achievement; and

supporting the creative

endeavors of departments,

colleges and the university.

In point of fact,

many proposals for Honors

programs were prepared at the

University.

Some .of the early

experiences at the M-Ith

Department have already

been mentioned.

The English Department

offered Honors sections

of Freshman

English so that able

students would be freed

from the rote and drill

of Basic

Composition.

Sometimes between 1963 and

1965 the College of

Physical Education,

Recreation, and Health

submitted a plan for

an Honors Program which

permitted

freshmen to formally apply

based on the high school

grade point average.

In

1961, the Psychology

Department also started

an Honors Program for junior

and

senior majors.

However, at least

up until the mid-1960's, Honors

was perceived to be a

department responsibility.

In 1963 the Alumni

Association submitted

a report

18

to President Elkins suggesting

that all Honors

programs at the University be

brought under the control

of a University Honors

director.

However, the Senate

Committees deliberating the

proposal rejected the idea

with the suggestion:

The present procedure of

vesting responsibility for

honors

programs in their respective fields

with faculties of the

various departments, held

more promise for success

at this

time than moving to

a University-wide director (Senate,

5/28/63).

The rejection of

a University-wide Honors director

suggests strong feeling that

Honors was a aepartmental

responsibility.

However, it is also indicative

of

the sentiment that

Honors programs should be

centrally organized and

perhaps

expanded.

The Beginning of General

Honors at UMCP

In January, 1962, the

University Senate approved

an Honors and special

studies program submitted

by the College of Arts

and Sciences.

The proposal

established a set of standards

for measuring all departmental

Honors and encom-

passed the following

broad guidelines:

Departmental Honors

were typically seen

as a way of providing

encouragement and recognition of

superior scholarship

of junior and senior

majors.

Students were to be given the

opportunity for

intensive and independent

studies in the hope of their

achieving integration

and depth in

a chosen field of study.

Successful completion of

an Honors pro-

gram would be determined by oral

and written ezcaminations

resulting in the

awarding of "highest

honors," "high honors,"

or "no honors."

The proposal by the College

of Arts and Sciences

also included the

sug-

gestion that opportunities

for freshmen, in pre-honors

courses and programs,

should be made available.

In suggesting that the

proposal be approved, the

General Committee

on Educational Policy emphasized "the

importance of the

pre-honors programs and the

opportunity for the freshmen

to be admitted to

the honors

programs... in the hope that gradually

the honors programs would

become generally available

beginning with the freshman year"

(Senate, 1/30/62).

Thus a new ingredient

to the definition of Honors was

introduced at the

University, namely, that

Honors should begin at the

beginning of a student's

academic career.

There are many possible

explanations for the expansion

of the definition

of Honors at the

University to include

a "General Honors Program."

General

19

-18-

Honors rttempted to

meet the needs of superior

students by providing

a more

personally suited intellectual

experience.

As the University

grew, General

Honors became a way of

making the University

appear less massive and imper-

sonal to incoming students.

During the growth

years of the 1950's and 1960's,

the University wanted

to communicate to students

that their intellectual

development was an important

part of their college experience

(Conversation

with R. Lee Hornbake).

Some departments encouraged

this personal identification.

Students

shared many of the

same classes; a prescribed

sequence of courses along with

requirements for upper level

courses contingent on lower level

prerequisites

promoted closer

student-to-student and

student-to-faculty interactions

(e.g.,

engineering).

This was not the

case for all departments and

general Honors

was a way to provide such

opportunities for able students

regardless of major.

General Honors supplemented

departmental efforts.

Freshmen and sophomores

with widely different

areas of interest were able

to participate in an environ-

ment suited to their abilities

stimulated by equally able

peers.

General Honors provided

opportunities for students

in their earliest

years to participate in

an enriched academic environment.

In practice, this

meant earlier identification

of potential Honors

students and a coordination

of efforts aimed

at providing appropriate

experiences.

The reader should

note that the idea of Honors

for freshmen and sopho-

mores was consistent with efforts

around the country

at providing opportunities

for able college students.

The.ICSS, from its inception,

promoted the idea

that Honors should

run continuously and cumulatively

through all four

years of

college.

The ICSS proposed less

emphasis on specialization

than had

been common.

It stressed the importance

of a four-year pro-

gram, one that would include both

general and departmental

honors.

Talented and otherwise

promising students, it

sug-

gested, should be identified

and made to participate

in honors

as early as possible

-- ideally at the time of college

entrance

(Cohen, 30).

In this sense, though

General Honors at College

Park may not have been

typical

of colleges in the

U.S., it was consistent with

the thinking of the

most impor-

tant intercollegiate honors

organization in the country,

the ICSS.

The develop-

ment of the General Honors

Program at College Park

was both consistent with

conventional wisdom of the

time and an innovative

approach at providing

a

program for able college students.

20

SURVEY RESULTS

In order to evaluate the impact of

the Honors programs, both within the

University community and in the general

population, the study managers. sent

questionnaires to school counselors in

public and private high schools, the

faculty who taught in the Honors

programs, students in General Honors, and

those students not in'General

Honors.

The results of these surveys

are

discussed in the following

sections.

Survey Results - Guidance Counselors

in Maryland

Survey questionnaires were. sent

to every public high school and half of

the private high schools in

Maryland.

A list of public school counselors

was

purchased from the Maryland School

Counselors Association.

A list of private

schools was provided by the Admissions

Office at UMCP.

The overall response to the

survey was good.

Of the 206 counselors mailed

copies of the surveys, 131 (63.5%)

returned the form.

The return rate from

the public schools was slightly higher

than that from private schools.

This

is attributed to the fact that letters

were addressed by name to the head of

guidance at each public school.

The breakdown of response is given

below.

Public School Counselors

Private School Counselors

Total

Contacted

168

Contacted

38

206

Responded

111

Responded

20

131

Counselors were asked to respond

to a number of questions concerning

their recommendations to students.

These responses are presented in tabular

Corm below.

I RECOMMEND THAT TALENTED AND GIFTED

STUDENTS ATTEND

THE UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND TO THE

FOLLOWING EXTENT:

Very often

15.3%

Sometimes

64.1%

Rarely

12.2%

Never

2.3%

MISSING

6.1%

100%

-20-

Counselors were asked to choose the most importa

reasons for recommending

that gifted and talented students attend the University.

The most often

chosen responses were:

Superior programs in student's major

64.1%

Special programs for gifted students

51.9%

Cost of tuition

35.9%.

Reputation of school

34.4%

***Multiple Responses Allowed

Counselors were asked if they were aware of the presence of the General

Honors Program and the department honors programs at UMCP.

I WAS AWARE THAT UMCP HAS A GENERAL HONORS PROGRAM

Yes 91.6%

No

5.3%

MISSING

3.1%

100%

I WAS AWARE THAT UMCP OFFERS DEPARTMENTAL HONORS IN SEVERAL AREAS

Yes

80.9%

No

18.3%

MISSING .8%

100%

Counselors were asked whether the presence of Honors programs at the

University influenced their recommendations to gifted and talented students:

Very much so

26.0%

Somewhat

57.3%

Barely

10.7%

Not at all

3.1%

MISSING

3.1%

100% (error due to rounding)

Finally, counselors were asked to respond to the statement:

OF THE INFORMATION THAT IS NECESSARY TO ADEQUATELY ADVISE

MY STUDENTS ABOUT HONORS PROGRAMS AT UMCP,

I NOW HAVE

More than enough

2.3%

Enough

56.5%

Less than enough

36.6%

None at all

3.1%

MISSING

'1.5%

100%

22

-21-

By separating the responses of public

and private high school guidance

coun-

selors, the following answers to the above

question were received.

OF THE INFORMATION

MY STUDENTS ABOUT

Pubiic H.S.

Counselors

THAT IS NECESSARY

HONORS PROGRAMS AT

TO ADEQUATELY ADVISE

UMCP, I NOW HAVE

Private H.S.

Counselors

1.8%

More than enough

5.0%

55.9%

Enough

60.0%

37.8%

Less than enough

30.0%

2.7%

None at all

5.0%

1.8%

MISSING

0.0%

100%

100%

This suggests a real need to distribute

information about Honors to counselors

at both public and private high schools in the

State.

Survey Results

Faculty Teaching Honori.

Surveys were distributed to 23 faculty members at'the

University.

In

most cases, these were given out during class time and

filled out at the same

time as students were filling out

a different questionnaire.

In a few cases

faculty members returned the form by mail.

What was most surprising

was that in the 25 or so classes visited during

the study, 23 teachers had taught

an Honors class.

The original intention had

been to make some comparisons between faculty

members who had taught Honors

and those that had not.

However, with only two faculty members in

the latter

category, it was not possible.

A basic impression is that most faculty members

would teach Honors given

the opportunity.

Basically, Lack of department

resources and/or lack of a

department program prevents a faculty member from

teaching Honors courses.

Faculty who had taught an Honors

course were asked what motivated them

to do so.

The response pattern was as follows:

I was invited to do so by the GHP

39.1%

I volunteered based on interest in gifted and talented

students

60.9%

I volunteered because of belief in the honors

approach

34.8%

I was approached by the department

39.1%

I was approached by students

8.7%

***Multiple Responses Allowed

23

-2?

This tends to support the view that faculty are motivated to tea,-.h Honors

for different reasons though interest in gifted students was the most often

cited response.

Faculty members were asked their impression of the intellectual climate

at the University since their arrival and responded:

Noticeably improved

4.3%

Improved a bit

56.5%

No change

30.4%

Declined noticeably

4.3%

MISSING 4.3%

100% (error due to rounding)

This suggests a pattern that more than half the faculty in the sample feel

that the intellectual climate at the University has improved at least somewhat.

Faculty were also asked how long they had been a member of the faculty-

at the University.

For the most part, the faculty were fairlyexperienced.

The pattern:

1 year or less

0

2-5 years

21.7%

6-10 years

34.8%

11-15 years

13.0%

16-20 years

17.4%

20+ years

13%

100% (error due to rounding)

This suggests that a fairly experienced faculty teach honors courses at the

University.

The explanation may be that teaching Honors is considered an

opportunity that only the most senior of faculty are able to enjoy.

If a

faculty member is really interested in teaching an honors class, he or she

may still riot be able to do so for one of a variety of reasons.

In unstructured interviews with faculty members, it'was also suggested

that different Honors courses are taught by different faculty.

Whereas some

faculty enjoy the seminar approach of Honors 100 and Howrs 300, others prefer

the more content oriented departmental Honors and H-Versions.

It was suggested

by one faculty member that those who teach one type are unlikely to teach the

ether.

-23-

In order to verify this point, faculty were asked the type of Honors courses

that they had taught and tesponded:

Departmental Honors courses

39.1%

(restricted to junior and senior majors)

Honors Seminars

39.1%

H-Versions

43.4%

The lack of overlap suggests that most of the faculty in the sample tended to

teach one type of Honors course only.

Faculty were asked the extent to which they felt that Honors programs con-

tribute to the intellectual climate on campus and answered:

Major contribution

43.5%

Contribution

43.5%

Minor contribution

8.7%

No contribution

4.3%

100.0%

Faculty were also asked the extent to which Honors contributed to their

satisfaction as teachers.

Their responses were:

Very much

56.5%

Somewhat

30.4%

Barely

8.7%

Not at all

4.3%

100.0% (error due to rounding)

Faculty were asked to choose the greatest benefits of having Honors programs

at the University.

The three most cited answers were:

Closer student-faculty interaction

70%

Opportunity to work with brightest

students 47.8%

Greater opportunity for students to

participate in class

34.87,

This seems to indicate an attitude of the faculty that Honors should he a lively

sort of class.

The opportunity to work with students, the brightest students,

is identified by faculty as the most desirable/beneficial aspect of Honors programs

on campus.

25

-74-

Faculty were asked to write down the one thing that they like about Honors

programs and the one thing they dislike.

The responses to these two items on the

questionnaire are listed below:

THE ONE THING I LIKE THE MOST ABOUT HONORS COURSES /PROGRAMS:

Brighter students

39.1%

Level of intellectual discourse

8.'7%

Educational alternative for gifted

students

17.4%

Interdisciplinary format

17.4%

MISSING

17.4%

100%

THE ONE THING I LIKE THE LEAST ABOUT HONORS COURSES/PROGRAMS:

Too few students

17.4%

Not enough publicity

8.7%

Exclusiveness of program 13%

Not exclusive enough

8.7%

Lack of support for faculty,

staff, facility

8.7%

Lack of continuity

4.3%

Lack of organized non-classroom

activities of an intellectual nature

4.3%

Intellectual failure of program

13%

Bureaucratic interference

4.3%

MISSING 21.7%

100% (error due to rounding)

The responses indicated that faculty derive a general satisfaction from

working with very bright students. The dislikes are more of a mixed bag. There

does seem to be a nr`e of dissatisfaction over the intellectual aspects of Honors

(:ourses.

This is not directed toward one program in particular, but to Honors in

-25-

Survey Results Departmental Honors Students

At the present time there are 31 departmental Honors programs at the Univer-

sity of Maryllnd College Park.

Most of these programs are for junior and senior

majors, though there are some exceptions.

For example, the Mathematics Department

offers a special Honors course sequence for freshmen and sophomore non-majors.

Enrollme,:t in these courses is based on demonstrated achievement (as indicated on

the SAT -oath or similar tests).

More typical at UMCP is the departmental Honors which requires a student to

have declared his/her major and also meet GPA requirements of between 3.0 and 3.5.

Students generally enter these programs in their fifth or sixth semester at the

University.

A department Honors student must fulfill the department's requirements for

graduation as well as the requirements for an Honors degree.

Questionnaires were distributed to Honors students from eight departments.

The selection of particular departments was not random.

Rather, the Dean of

Undergraduate Studies sent letters to ten departments asking for permission to

distribute the surveys.

Unlike the CUP, the departmental programs are much smaller.

Therefore, the

number of students that were asked to fill out the surveys was much smaller.

The

departments that participated in the study were:

Chemistry, English, History,

Mathematics, Physics, Psychology, Zoology, and Law Enforcement.

Except for six

students from the Mathematics Department and one from the English Department, all

students had completed at least sixty credits of University work.

The sample was made up of 25 males and 15 females.

The difference in males

and females may be indicative of the differences in the numbers of men and women

pursuing honors, or the fact that two of'the eight departments represent science

departments and one Mathematics, all of which have larger numbers of men than women.

The Grade Point Average of the students in the sample were:

2.00

2.99

3.00

3.59

3.60

4.00

7.5%(3)

55.0%(22)

37.5%(15)

Over 90 percent of the students had GPA's of. 3.0 or better.

rho students were -Isked whether they were or Ilad been members of the General

Honors Program.

Fifteen departmental honors students (37.5%) said Yes to this

-26-

question.

This supports the suggestion that/ the General Honors Program serves

as a feeder to the departmental. Honors pro i-ams.

However, when asked how they

first learned of the departmental programs, only three students (7.5%) indicated

that the GHP was the source of their information.

Student response to the question of how the departmental Honors programs

were first learned about suggests that the faculty plays the most important role

in this recruitment.

Twenty-two students (55%) say that they first learned about

the departmental Honors program that they are in from a faculty member.

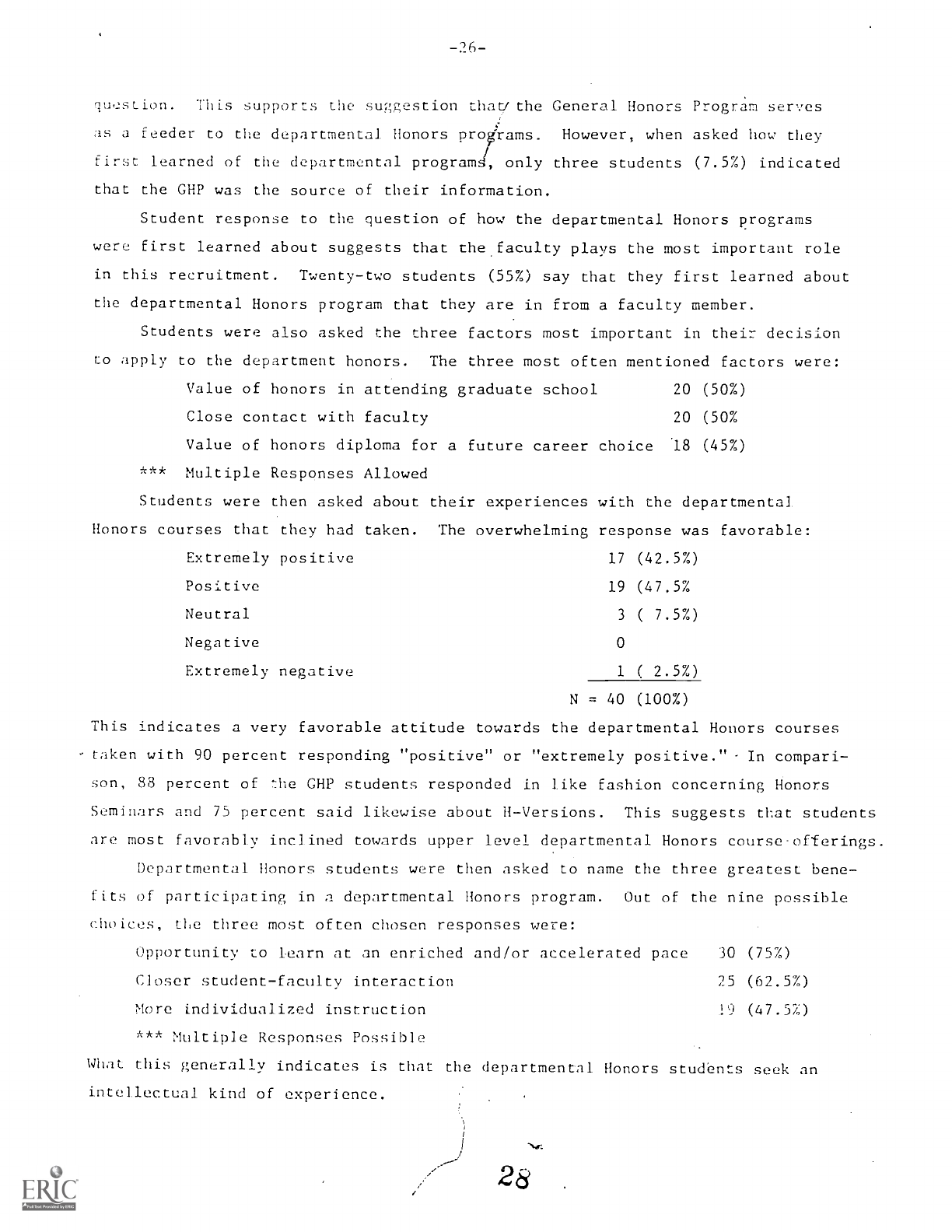

Students were also asked the three factors most important in their decision

to apply to the department honors.

The three most often mentioned factors were:

Value of honors in attending graduate school

20 (50%)

Close contact with faculty

20 (50%

Value of honors diploma for a future career choice

18 (45%)

***

Multiple Responses Allowed

Students were then asked about their experiences with the departmental.

Honors courses that they had taken.

The overwhelming response was favorable:

Extremely positive

17 (42.5%)

Positive

19 (47.5%

Neutral

3 ( 7.5%)

Negative

0

Extremely negative

1 ( 2.5%)

N = 40 (100%)

This indicates a very favorable attitude towards the departmental Honors courses

taken with 90 percent responding "positive" or "extremely positive."

In compari-

son, 88 percent of

lie GHP students responded in like fashion concerning Honors

Seminars and 75 percent said likewise about H-Versions.

This suggests that students

are most favorably inclined towards upper level departmental Honors course-offerings.

Departmental Honors students were then asked to name the three greatest bene-

fits of participating in a departmental Honors program.

Out of the nine possible

choices, tie three most often chosen responses were:

Opportunity to Learn at an enriched and/or accelerated pace

30 (75%)

Closer student-faculty interaction

25 (62.5%)

More individualized instruction

19 (47.5%)

*** Multiple Responses Possible

What this generally indicates is that the departmental Honors

students seek an

intellectual kind of experience.

28

-27-

Survey 1:esults

Students in the General Honors Program

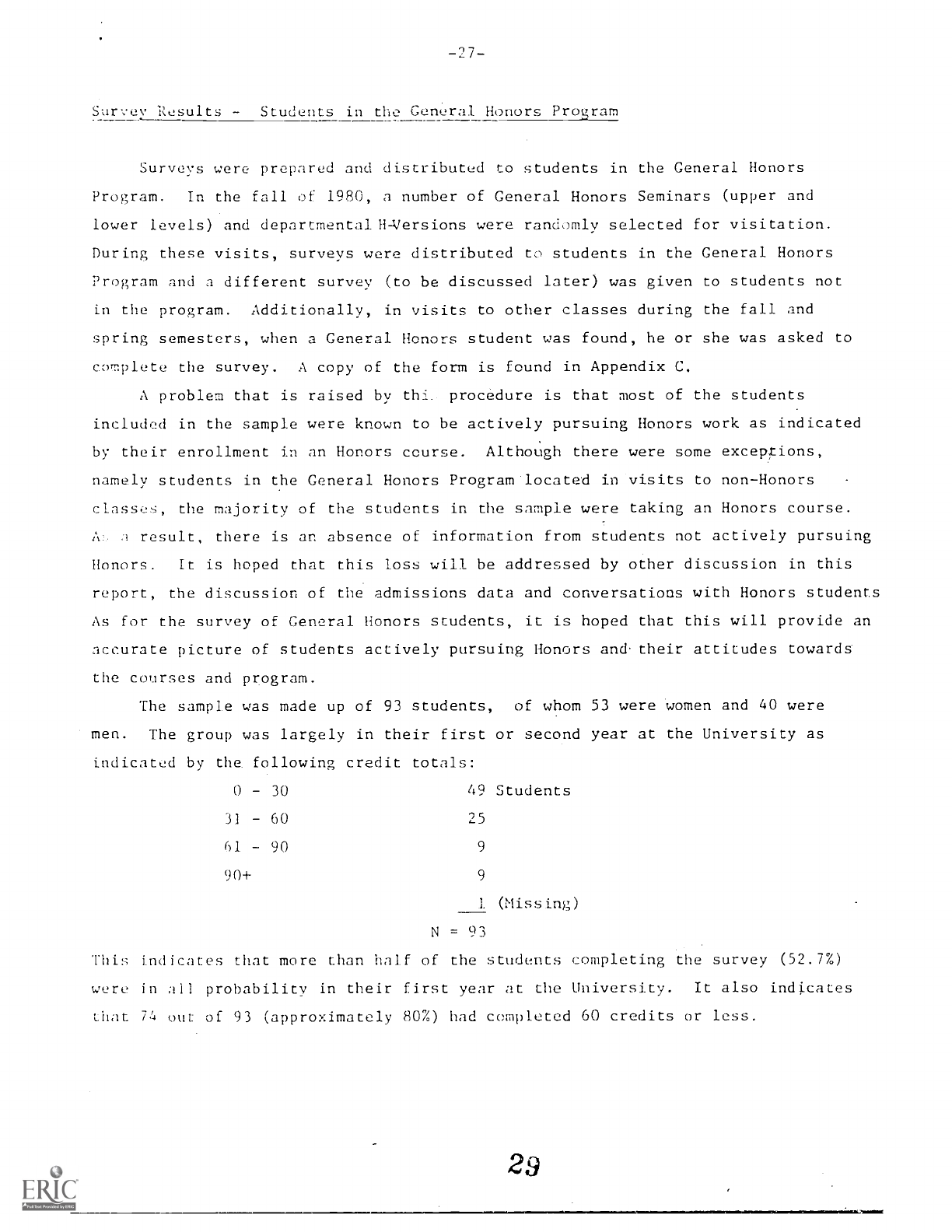

Surveys were prepared and distributed to students in the General Honors

Program.

In the fall of 1980, a number of General Honors Seminars (upper and

lower levels) and departmental H-Versions were randomly selected for visitation.

During these visits, surveys were distributed to students in the General Honors

Program and a different survey (to be discussed later) was given to students not

in the program. Additionally, in visits to other classes during the fall and

spring semesters, when a General Honors student was found, he or she was asked to

complete the survey. A copy of the form is found in Appendix C.

A problem that is raised by thi.

procedure is that most of the students

included in the sample were known to be actively pursuing Honors work as indicated

by their enrollment in an Honors course.

Although there were some exceptions,

namely students in the General Honors Program locate.d in visits to non-Honors

classes, the majority of the students in the sample were taking an Honors course.

result, there is an absence of information from students not actively pursuing

Honors.

It is hoped that this loss will be addressed by other discussion in this

report, the discussion of the admissions data and conversations with Honors students

As for the survey of General Honors students, it is hoped that this will provide an

accurate picture of students actively pursuing Honors and their attitudes towards

the courses and program.

The sample was made up of 93 students,

of whom 53 were women and 40 were

men.

The group was largely in their first or second year at the University as

indicated by the_ following credit totals:

0 30

49 Students

31

60 25

01

90 9

90+

9

1. (Missing)

N = 93

This indicates that more than half of the students completing the survey (52.7%)

were in all probability in their first year at the University.

It also indicates

that 74 out: of 93 (approximately 80%) had completed 60 credits or less.

29

-78-

The Grade Point Average of this group was as follows:

0.00

1.99 0

2.00 - 2.99

7

.00 3.59 26

3.60

4.00

38

MISSING

22

N = 93

This suggests that over 90 percent of those responding to the question had CPA's

of 3.00 and over. Further, that 53.5 percent of those responding had CPA's of

3.6 and above. The high number of no responses (MISSING) is attributable to the

fact that many students were in the first semester of their, freshman year, and had

not yet earned a GPA at the University.

The students were asked how they first learned about the General Honors Pro-

gram and were given a range of responses to choose from.

Students were allowed

to choose more than one response to the question.

The most often chosen way in

which students first ler,.rned about the General Honors Program was from the high

school guidance counsel( :

Forty-one students (44.1%) answered in this way.

This

is followed closely by statements that they first learned about the GHP from

University recruitment (39.8%) and from the University application booklet (39.8%).

Since students were allowed to choose more than one answer, it seems that there

is a simultaneous impact of these three factors:

guidance counselor, application

booklet and recruitment efforts.

Since guidance is the number one rated answer,

it seems important to make sure that guidance counselors in the state have enough

information on the Honors programs at UM.

This does not seem to be the case if

one refers to the guidance issue.

(Recall that approximately 40% of guidance

counselors in the state responded that they had less than enough or no information

at all concerning Honors programs at UM.)

This seems to indicate a need to coor-

dinate efforts at providing information about honors at UMCP/University of Maryland.

Students were asked the three most important factors in their decision to

apply to the General Honors Program.

Eighty-two percent raced small classes in

their top thre choices.

Also highly rated by students were the intellectual

challenge (65.5%) and the value of Honors on a future career choice (42%).

Rated

on the low end of the scale of choices by students was scholarship possibilities

(only

I .student chose this as his/her third choice).

On-,2ampus housing was

30

-29-

chosen by 17.3 percent of General Honors students as one of their three most

important factors in the decision to apply to the General Honors Program.

Students were also asked to judge the significance of the existence of the

General Honors Program in their decision to apply to UMCP.

Students were asked:

THE FACT THAT A GENERAL HONORS PROGRAM EXISTS AT THE UNIVERSITY

OF MARYLAND INDUCED ME TO APPLY FOR ADMISSION TO THE UNIVERSITY

Very much

35.5%

Somewhat 25.8%

Hardly

15.1%

Not at all

23.7%

100.0%** (error due to rounding)

From this, over 60 percent of students responded that the existence of the

General Honors Program influenced their decision to apply to UM.

A parallel question asked students the extent to which their acceptance by

the GHP helped them decide to attend the University.

Very much

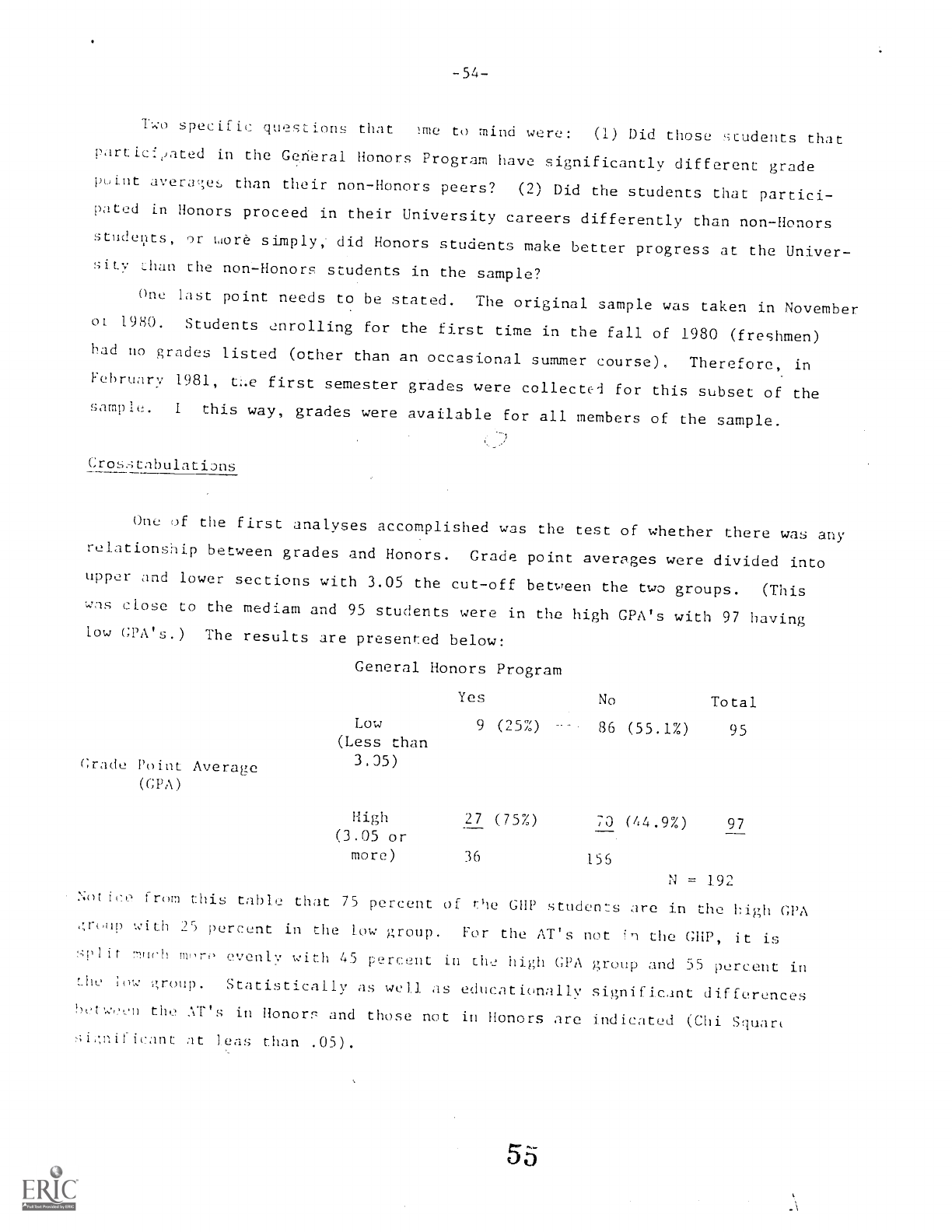

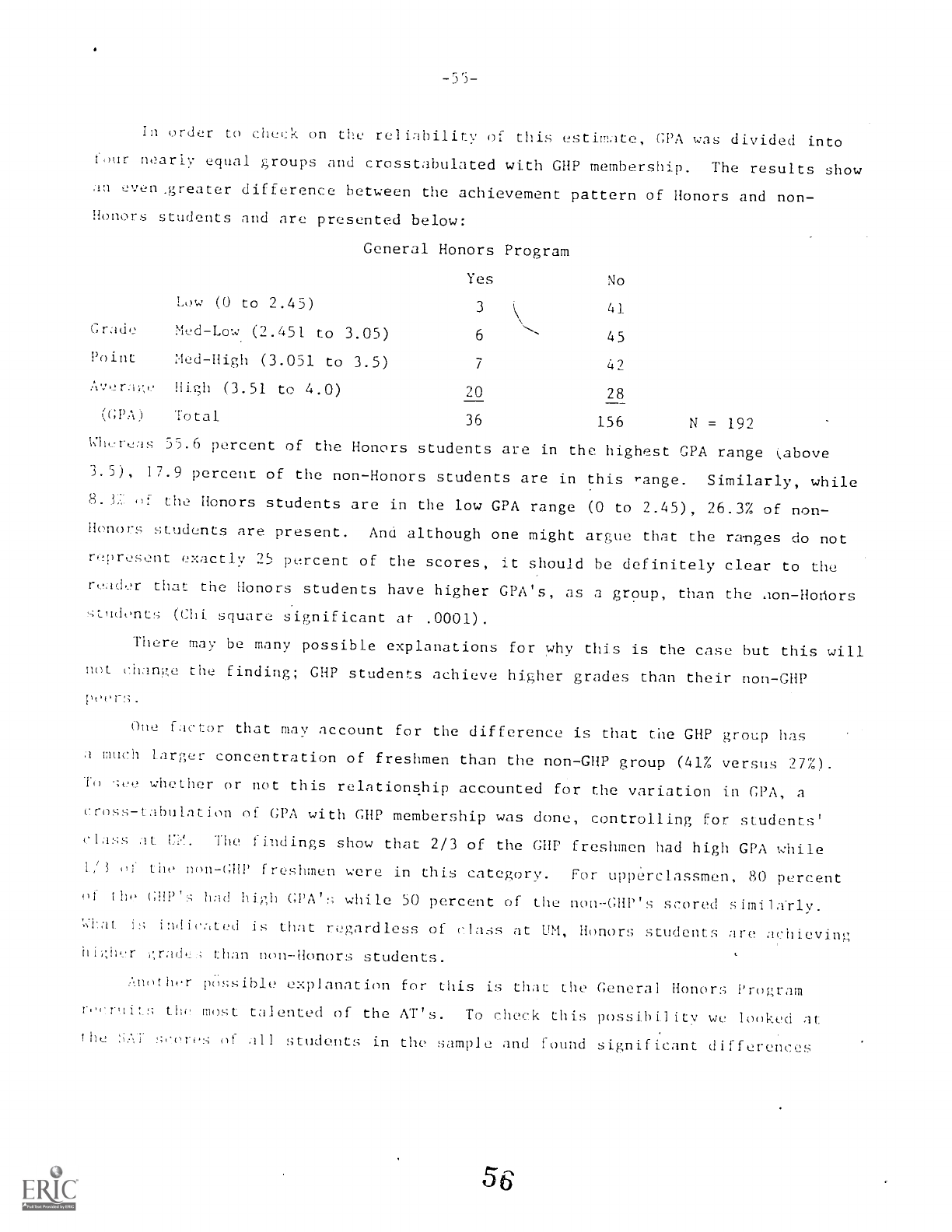

38.7% (36)