Healthcare Provision in Bangladesh

Medical Country of Origin Information Report

June 2023

Manuscript completed in 03/2023

Neither the European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA) nor any person acting on behalf of the

EUAA is responsible for the use that might be made of the information contained within this

publication.

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2023

PDF ISBN 978-92-9403-287-4 doi: 10.2847/913591 BZ-07-23-194-EN-N

© European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA), 2023

Cover photo/illustration: Indian people taking medicines, Rawpixel.com, © Adobe Stock

188476312, n.d.

Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. For any use or reproduction

of photos or other material that is not under the EUAA copyright, permission must be sought

directly from the copyright holders.

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

3

Acknowledgements

The EUAA acknowledges International SOS as the drafters of this report.

The report has been reviewed by International SOS and EUAA.

EUROPEAN UNION AGENCY FOR ASYLUM

4

Contents

Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ 3

Contents .......................................................................................................................................... 4

Disclaimer ........................................................................................................................................ 6

Glossary and abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 7

Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 12

Terms of reference ........................................................................................................ 12

Collecting information ................................................................................................... 12

Currency ........................................................................................................................... 12

Quality control ................................................................................................................. 12

1. General information .......................................................................................................... 15

1.1. Geographic context .................................................................................................................. 15

1.2. Demographic context ............................................................................................................... 16

1.3. Economic context ...................................................................................................................... 16

1.4. Vulnerable groups ...................................................................................................................... 17

1.4.1. Rohingya refugees ................................................................................................ 17

2. Healthcare system ............................................................................................................ 19

2.1. Health system organisation .................................................................................................... 19

2.1.1. Overview ................................................................................................................ 19

2.1.2. Public sector ....................................................................................................... 24

2.1.3. Private sector ...................................................................................................... 28

2.2. Healthcare resources .............................................................................................................. 30

2.3. Pharmaceutical sector ............................................................................................................. 30

2.4. Patient pathways ....................................................................................................................... 33

3. Economic factors .............................................................................................................. 34

3.1. Health services provided by the State / Public authorities ............................................ 34

3.2. Risk-pooling mechanisms ...................................................................................................... 35

3.2.1. Public health insurance, national or state coverage ................................ 35

3.2.2. Community-based health insurance schemes ......................................... 36

3.2.3. Private insurance companies ......................................................................... 37

3.3. Out-of-pocket health expenditure ....................................................................................... 39

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

5

3.3.1. Cost of consultations ........................................................................................ 42

3.3.2. Cost of medication ............................................................................................ 43

4. List of useful links ............................................................................................................. 45

Annex 1: Bibliography .................................................................................................................. 47

Annex 2: Terms of Reference ...................................................................................................... 58

EUROPEAN UNION AGENCY FOR ASYLUM

6

Disclaimer

This report was written according to the EUAA COI Report Methodology (2023). The report is

based on carefully selected sources of information. All sources used are referenced.

The information contained in this report has been researched, evaluated and analysed with

utmost care. However, this document does not claim to be exhaustive. If a particular event,

person or organisation is not mentioned in the report, this does not mean that the event has

not taken place or that the person or organisation does not exist.

Furthermore, this report is not conclusive as to the determination or merit of any particular

application for international protection. Terminology used should not be regarded as

indicative of a particular legal position.

‘Refugee’, ‘risk’ and similar terminology are used as generic terminology and not in the legal

sense as applied in the EU Asylum Acquis, the 1951 Refugee Convention and the 1967

Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees.

Neither the EUAA, nor any person acting on its behalf, may be held responsible for the use

which may be made of the information contained in this report.

The drafting of this report was finalised on 3 May 2023. Any event taking place after this date

is not included in this report.

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

7

Glossary and abbreviations

Term

Definition

8FYP

8

th

Five Year Plan for Bangladesh

ADB

Asian Development Bank

AMC

Antimicrobial Consumption

BDT

Bangladeshi Taka [currency]

BIDA

Bangladesh Investment Development Authority

CBHI

Community-Based Health Insurance

CC

Community Clinic

Chars

Riverine sand and silt landmasses which are home to over

5 million people.

CHCP

Community Health Care Providers

CHE

Current Health Expenditure: estimates of current health

expenditures include healthcare goods and services consumed

during each year. This indicator does not include capital health

expenditures such as buildings, machinery, IT and stocks of

vaccines for emergency or outbreaks.

1

CHT

Chittagong Hill Tracts

CMSD

Central Medical Store Depot

1

World Bank (The), Current health expenditure (% of GDP), 2023, url

EUROPEAN UNION AGENCY FOR ASYLUM

8

Term

Definition

COI

Country of Origin Information

CPP

Certificate for Pharmaceutical Products

DGDA

Directorate General of Drug Administration

DGFP

Directorate General of Family Planning

DGHS

Directorate General of Health Services

DGMEFW

Directorate General of Medical Education and Family Welfare

DGNM

Directorate General of Nursing and Midwifery

EASO

European Asylum Support Office

EPI

Expanded Programme on Immunization

ESP

Essential Health Services Package

EU

European Union

EU+ countries

Member States of the European Union and associated countries

EUAA

European Union Agency for Asylum

FDMN

Forcefully Displaced Myanmar Nationals

FSC

Free Sales Certificate

FWA

Family Welfare Assistant

FWV

Family Welfare Visitor

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

9

Term

Definition

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

GED

General Economics Division

GMP

Good Manufacturing Practices Certificate

HA

Health Assistant

Haor

A wetland habitat in Bangladesh's north-eastern region that is

geographically a shallow depression in the form of a bowl or

saucer, also known as a back swamp, with a combined area of

approximately 2 million hectare (1 ha =2.471 acres) and population

of approximately 19.37 million inhabitants.

HCFC

Health Care Financing Strategy

HIES

Household Income and Expenditure Survey

HPNSDP

Health Population and Nutrition Sector Development Programme

HNPSIP

Health Nutrition Population Sector Strategic Investment Plan

HPNSP

Health, Population and Nutrition Sector Programme

HPSP

Health Population Sector Programme

HSD

Health Services Division

icddr,b

International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh

IDP

Internally Displaced People

IDRA

Insurance Development and Regulatory Authority

EUROPEAN UNION AGENCY FOR ASYLUM

10

Term

Definition

LGD

Local Government Division

MCWC

Maternal and Child Welfare Centre

MedCOI

Medical Country of Origin Information

MEFWD

Medical Education and Family Welfare Division

Member States

Member States of the European Union

MO

Medical Officer

MOF

Ministry of Finance

MOHFW

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare

MOLGRDC

Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and

Cooperatives

NCD

Non-Communicable Disease

NCL

National Control Laboratory

NGO

Non-Governmental Organisation

NGO-MFI

NGO Microfinance Institute

NIPORT

National Institute of Population Research & Training

OOPE

Out of Pocket Expense

OPD

Outpatient Department

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

11

Term

Definition

OTC

Over the Counter

PDAB

Permanent Total Disability Insurance

RMG

Ready-Made Garment

RMO

Resident Medical Officer

SACMO

Sub-Assistant Community Medical Officer

SBC

Sadharan Bima Corporation

SSK

Shasthyo Shurokhsha Karmasuchi

SWAp

Sector-Wide Approach

THE

Total Health Expenditure: the sum of public and private health

expenditure. It covers the provision of health services (preventive

and curative), family planning activities, nutrition activities, and

emergency aid designated for health but does not include

provision of water and sanitation.

2

UHFPO

Upazila Health and Family Planning Officers

UHFWCs

Union Level Facilities

Upazila

An administrative unit, which is a subdivision of a district formerly

known as "thana". Bangladesh has 495 Upazilas.

UPFO

Upazila Family Planning Officer

USD

United States Dollar

2

World Bank (The), Health expenditure, total (% of GDP), 2023, url

EUROPEAN UNION AGENCY FOR ASYLUM

12

Introduction

Methodology

The purpose of the report is to provide information on access to healthcare in Bangladesh.

This information is relevant to the application of international protection status determination

(refugee status and subsidiary protection) and migration legislation in EU+ countries.

Terms of reference

The terms of reference for this Medical Country of Origin Information Report can be found in

Annex 2. The drafting period finished on 27 January 2023, peer review occurred between 27

January - 10 February 2023, and additional information was added to the report as a result of

the quality review process during the review implementation up until 10 March 2023. The

report was internally reviewed subsequently.

Collecting information

EUAA contracted International SOS (Intl.SOS) to manage the report delivery including data

collection. Intl.SOS recruited and managed a local consultant to write the report and a public

health expert to edit the report. These were selected from Intl.SOS’ existing pool of

consultants. The consultant was selected based on their experience in leading comparable

projects and their experience of working on public health issues in Bangladesh.

This report is based on publicly available information in electronic and paper-based sources

gathered through desk-based research. This report also contains information from multiple

oral sources with ground-level knowledge of the healthcare situation in Bangladesh who were

interviewed specifically for this report. For security reasons, all oral sources are anonymised.

Currency

The currency in Bangladesh is the Bangladeshi taka (BDT). The currency name, the ISO code

and the conversion amounts are taken from the INFOEURO website of the European

Commission. The rate used is that prevailing at the date of the source, i.e. the publication or

the interview, that is being cited. The prevailing rate is taken from The European Commission

website, InforEuro.

3

Quality control

This report was written by Intl.SOS in line with the European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA)

COI Report Methodology (2023)

4

, the EUAA Country of Origin Information (COI) Reports

3

European Commission, Exchange rate (InforEuro), n.d., url

4

EUAA, Country of Origin Information (COI) Report Methodology, February 2023, url

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

13

Writing and Referencing Guide (2023)

5

and the EUAA Writing Guide (2022)

6

. Quality control of

the report was carried out both on content and form. Form and content were reviewed by

Intl.SOS and EUAA.

The accuracy of information included in the report was reviewed, to the extent possible,

based on the quality of the sources and citations provided by the consultants. All the

comments from reviewers were reviewed and were implemented to the extent possible, under

time constraints.

Sources

In accordance with EUAA COI methodology, a range of different published sources have been

consulted on relevant topics for this report. These include: governmental publications,

academic publications, reports by non-governmental organisations and international

organisations, as well as Bangladeshi media.

In addition to using publicly available sources, three oral sources were contacted for this

report. The oral sources are all officers in the MOHFW and they are anonymised in this report

for security reasons. The sources were assessed for their background and ground-level

knowledge. All oral sources are described in the Annex 1: Bibliography. Key informant

interviews were carried out in February 2023.

5

EUAA, Country of Origin Information (COI) Reports Writing and Referencing Guide, February 2023, url

6

EUAA, The EUAA Writing Guide, April 2022, url

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

15

1. General information

The Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh establishes the role of the State in

‘planned economic growth’ and ‘improvement in the material and cultural standard of living of

the people’. The government is responsible to its citizens for their basic needs, for example,

‘food, clothing, shelter, education and medical care’ (article 15(a)).

8

Article 18(1) of the

constitution establishes that the State shall have regard to ‘raising the level of nutrition and the

improvement of public health’ (article 18(1)).

9

1.1. Geographic context

Bangladesh covers 147 570 square kilometres,

10

and is densely populated with approximately

1 286 people per square kilometre.

11

It is the world’s seventh most climate risk-affected

country, with 185 extreme events recorded and 0.38 fatalities per 100 000 inhabitants

between 2000 and 2019.

12

According to a 2022 World Bank report, climate-related cyclones,

flooding, drought, change of disease patterns and loss of agricultural lands threaten

communities causing disproportional damage and disrupting lives and livelihoods. Floods

have caused severe economic impacts in Bangladesh, while cyclones are responsible for the

highest number of deaths. Heat stress, river and coastal flooding and landslides are predicted

to increase between 2041 and 2060 with devastating effects even under low-emission

scenarios.

13

In 2022, the World Bank reported on challenges facing Bangladesh: the capital and the

largest city Dhaka faces air pollution, water logging, poor waste disposal and traffic

congestion, while Chattogram and Khulna are exposed to risks related to their coastal

geographic location. Low-income residents are more exposed to these risks and face

inadequate water supply and sanitation, high population density and poor housing quality.

14

The use of solid fuels as primary cooking fuels, mostly wood and crop residues, increases

indoor air pollution and has adverse effects on the health of women and children.

15

A 2019

survey found that only 19 % of the population reported a primary reliance on clean fuels and

technologies for cooking and lighting.

16

8

Bangladesh, Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, 1972, url

9

Bangladesh, Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, 1972, url

10

World Bank (The), Surface area (sq. km) - Bangladesh, 2023, url

11

World Bank (The), Population density (people per sq. km of land area) - Bangladesh, 2023, url

12

Eckstein D. et al., Global Climate Risk Index 2021, Germanwatch, January 2021, url, p. 13

13

World Bank (The), Bangladesh Country Climate and Development Report, October 2022, url, p. 12

14

World Bank (The), Bangladesh Country Climate and Development Report, October 2022, url, p. 10

15

World Bank (The), Bangladesh Country Climate and Development Report, October 2022, url, p. 10

16

Bangladesh, BBS, Progotir Pathey, Bangladesh Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2019, Key Findings, 2019, url,

p. 11

EUROPEAN UNION AGENCY FOR ASYLUM

16

Bangladesh is vulnerable to environmental change, it is densely populated and will continue

to experience population increases through to 2050, by when it could have 13.3 million

internal climate migrants.

17

1.2. Demographic context

Bangladesh is undergoing social and demographic change, including urbanization and

industrialisation.

18

The population has increased from 50 million in 1960 to 169 million in

2021.

19

The 2017-2018 Demographic and Health Survey reports that 32 % of the population is

below 15 years of age.

20

Life expectancy at birth has increased from 50, in 1972, to 72 in

2020.

21

Migration from rural areas to urban areas is increasing. In 1960, 95 % of the population lived in

rural areas while in 2021 it was 61 %.

22

Bangladesh has a rural network of public sector health

services but lacks an equivalent network in the urban areas.

23

As a result, the poorest part of

the population living in urban areas is deprived of essential health care services.

24

A rapid and

consistent inflow of migrants provides an additional source of pressure on services in urban

slums and large cities.

25

Bangladesh is also undergoing an epidemiological transition, especially in its urban areas.

Shafique et al. cite studies from 2016 to 2019 on non-communicable diseases (NCDs) among

the urban poor in Bangladesh as showing increases in obesity and hypertension, with the

prevalence of hypertension in urban areas being more than double that of rural areas.

Hypertension and diabetes are also prevalent among urban slum dwellers in Dhaka, with

women reporting higher prevalence rates.

26

1.3. Economic context

In 2022, the World Bank reported that Bangladesh has been among the fastest growing

economies in the world, with annual per capita income growth of 4.0 % between 1990 and

2020, during which the country transited from a mainly agricultural economy to an industry

and services dominated economy.

27

Ready-made garment (RMG) exports, remittances from

17

World Bank (The), Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration, 2018, url, p. 144

18

Bangladesh, GED, 8th Five Year Plan, July 2020 - June 2025, Promoting Prosperity and Fostering Inclusiveness,

December 2020, url, p. 587

19

World Bank (The), Population Total Bangladesh, 2023, url

20

Bangladesh, NIPORT, Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18, October 2020, url, p. 14

21

World Bank (The) Data, Life expectancy at birth, total (years) – Bangladesh, 2023, url

22

World Bank (The) Data, Rural population (% of total population) – Bangladesh, 2023, url

23

Bangladesh, MOLGRDC, National Urban Health Strategy, November 2014, url, p. 6

24

Bangladesh, MOLGRDC, National Urban Health Strategy, November 2014, url, p. 6

25

Bangladesh, GED, 8th Five Year Plan, July 2020 - June 2025, Promoting Prosperity and Fostering Inclusiveness,

December 2020, url, p. 587

26

Shafique, S. et al., Epidemiological Transition and Non-Communicable Diseases among Urban Poor in

Bangladesh: A Knowledge Synthesis, 2019, url, p. 4

27

World Bank (The), Bangladesh Country Climate and Development Report, October 2022, url, p. 8

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

17

the Bangladeshi diaspora, stable macroeconomic conditions and domestic consumption

contribute to this growth.

28

Income levels are rising: the Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) 2016 found the

national average monthly household income to be BDT 15 945 (EUR 168). Monthly household

incomes were found to differ between urban and rural areas being BDT 22 565 (EUR 237) and

BDT 13 353 (EUR 140) respectively. This is an increase since 2010, of 38.90 % at the national

level and of 36.96 % in urban and 38.40 % in rural areas.

29

The increase in non-communicable

diseases is partially attributed to poor nutrition related to lifestyle changes.

30

1.4. Vulnerable groups

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW) identified hard to reach populations and

the disadvantaged including:

• specific populations: there are an estimated 2.5 million people who are members of

[minority] ethnic populations. 42 % reside in three hill districts of the Chittagong Hill

Tracts (CHT), while others are dispersed in hilly regions in the north and some coastal

districts. They belong to 45 different communities with low percentages of literacy and

nutritional status. These communities are poorly served by health facilities and it is

difficult to attract health workers to work in these remote areas;

• people with disabilities: many preventable disabilities are due to poverty, and disabled

girls face additional problems such as sexual abuse and marginalisation;

• elderly: elderly women are particularly affected, socially and economically, due to

widowhood and poverty;

• geographically excluded: populations in the chars, the haor areas and the remote

coastal areas where access is difficult, especially during rainy season; and

• professionally marginalized and socially excluded groups: including, but not limited to,

sweepers and sex workers who are also impoverished, who may not be aware of the

health consequences of their professional activities, and who are unable to take

preventive or curative measures or to change occupations.

31

1.4.1. Rohingya refugees

As of October 2022, more than 943 000 stateless Rohingya refugees are settled in Ukhiya

and Teknaf Upazilas, in the Southernmost coastal part of the country. The majority live in 34

28

World Bank (The), The World Bank in Bangladesh, 6 October 2022, url; ADB, Bangladesh, Asian Development

Bank Fact Sheet, July 2022, url, p. 1

29

Bangladesh, BBS, Preliminary Report on Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2016, October 2017, url,

pp. 21-22

30

Bangladesh, GED, 8th Five Year Plan, July 2020 - June 2025, Promoting Prosperity and Fostering Inclusiveness,

December 2020, url, p. 587

31

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Strategic Plan for Health Population and Nutrition Sector Development Program (HPNSDP)

2011-16, 2011, url, p. 25

EUROPEAN UNION AGENCY FOR ASYLUM

18

camps, the largest of which, Kutupalong-Balukhali Expansion Site, is host to more than

635 000 people.

32

The Government of Bangladesh refers to Rohingya refugees as Forcefully Displaced Myanmar

Nationals (FDMN).

33

The camps have been described as ‘crowded and unsafe’ and the

Bangladeshi government as keeping ‘restrictive policies’, for instance not allowing permanent

homes and restricting education and movement.

34

Public hospitals are facing increased

demand.

35

Crime rates have increased in the areas of the camps. Repatriation is regarded as

the goal of the Bangladeshi authorities, who are yet to allow any Rohingya to assimilate into

Bangladeshi society.

36

International Crisis Group states that the Government of Bangladesh is concerned that

planning for Rohingya refugees to remain in Bangladesh over the medium to long term would

relax international pressure on the Myanmar government and delay the creation of conditions

for the refugees’ safe and dignified return. The government is also concerned that further

waves of migration would occur if the conditions for Rohingya refugees were to improve in

Bangladesh and if they were to be allowed to integrate into Bangladeshi society.

37

It is also

noted by another source that the Government of Bangladesh is concerned that relaxing its

stance on repatriation would be ‘politically unpopular domestically’.

38

The government has so

far received USD 690 million in grants from Multi-Lateral Development Banks for longer-term

needs in Cox’s Bazar district and co-finances some activities. These funds are directed to a

range of sectors, including water and sanitation, health, social assistance, infrastructure and

disaster risk reduction.

39

32

UNOCHA, Rohingya Refugee Crisis, n.d., url

33

Rashid, R. et al., A descriptive study of Forcefully Displaced Myanmar Nationals (FDMN) presenting for care at

public health sector hospitals in Bangladesh, 2021, url, p. 1

34

Guardian (The), ‘Like an open prison’: a million Rohingya refugees still in Bangladesh camps five years after crisis,

23 August 2022, url

35

Rashid, R. et al., A descriptive study of Forcefully Displaced Myanmar Nationals (FDMN) presenting for care at

public health sector hospitals in Bangladesh, 2021, url, p. 1

36

Anwar A., Does Anyone Want to Solve the Rohingya Crisis?, The Diplomat, 2 February 2023, url

37

International Crisis Group, A Sustainable Policy for Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh, 27 December 2019, url,

p. 10

38

Development Initiatives, Supporting Longer Term Development in Crises at the Nexus, Lessons from Bangladesh,

2021, url, p. 32

39

Development Initiatives, Supporting Longer Term Development in Crises at the Nexus, Lessons from Bangladesh,

2021, url, p. 37

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

19

2. Healthcare system

2.1. Health system organisation

2.1.1. Overview

The MOHFW is responsible for developing national policies and for planning and decision-

making. MOHFW is financed through central government and through development budgets

and financing from external partners.

40

The Ministry and its regulatory bodies exert control

over the private sector and NGO facilities through rules and regulations.

41

In 2017, the MOHFW

created two divisions: the Health Services Division (HSD) and the Medical Education and

Family Welfare Division (MEFWD).

42

Each division is headed by a secretary who works under

the direction of the Minister of Health.

43

Figure 1. Organogram of the MOHFW, 2020

44

The HSD is responsible for nursing and midwifery; finance and audit; world health and public

health and drug administration and law.

45

Its mission is to ensure the delivery of affordable

quality healthcare for across Bangladesh.

46

The MEFWD is responsible for family planning and

medical education.

47

There are ten implementing authorities under the MOHFW and the head of each of these

holds the title of Director General.

48

The Directorate Generals of Health Services (DGHS) and

of Medical Education and Family Welfare (DGMEFW) are each implementing authorities under

the MOHFW. DGHS delivers and monitors routine health services directly.

49

DGMEFW

prepares and implements policies relating to medical education and family planning.

50

Each of

40

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Nutrition Population Sector Strategic Investment Plan, February 2016, url, p. 47

41

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2019, 2020, url, p. 9

42

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2019, 2020, url, p. 9

43

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2019, 2020, url, p. 10

44

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2020, 2022, url, p. 25

45

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2020, 2022, url, pp. 26

46

Bangladesh, MOHFW, [Mission of HSD], n.d., url

47

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2020, 2022, url, pp. 27

48

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2020, 2022, url, pp. 28

49

Bangladesh, DGHS, About us, n.d, url

50

Bangladesh, MOF, [Annual Report, Financial Year 2021-2022], October 2022, url,

p. 66

EUROPEAN UNION AGENCY FOR ASYLUM

20

these Directorate Generals operates along the eight administrative divisions of the country

(see Table 1).

The Health Population Nutrition Sector Development Plan (HPNSDP) is one of the main policy

documents for the MOHFW and brings the different health and nutrition programmes into a

single plan. This unifies programmes that had previously been supported by different donors

and planned and implemented by different government departments. The unified approach is

called the Sector Wide Approach (SWAp) and it aims to avoid duplication, improve efficiency

and reduce resource allocation. SWAp was launched in 1998.

51

Each HPNSDP is supported by

an Implementation Programme

52

and an Operational Plan. The Operational Plan set out details

of programme activities along with detailed budgets across the different programmes.

53

At the

time of writing the fifth HPNSDP is being prepared.

a) Administrative structure

This section presents the administrative structure in Bangladesh and shows how the

healthcare system maps onto this structure. It then introduces the Essential Health Service

Package (ESP) and its four tiers.

Table 1 (below) shows the administrative structure across Bangladesh. Bangladesh has eight

regional Divisions: Dhaka, Chattogram, Rajshahi, Khulna, Sylhet, Barisal, Rangpur and

Mymensingh.

54

These are local government bodies and distinct administrative units which are

administered under the Local Government Division (LGD) through elected representatives.

55

There are then Districts, Upazilas, Unions, Wards and Villages.

56

Local government in urban

areas is provided through the City Corporation and the Pourashava (Municipality). There are

12 City Corporations and 330 Municipalities across Bangladesh.

57

51

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Population and Nutrition Sector Development Program 2011-16, Program

Implementation Plan, July 2011, url, p. XV

52

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Population and Nutrition Sector Development Program 2011-16, Program

Implementation Plan, July 2011, url, pp. 33-34

53

Bangladesh, MOHFW, 4th Health, Population and Nutrition Sector Program 2017-2022, Operational Plan, April

2017, url

54

Bangladesh, Bangladesh National Portal, [Divisions], 25 April 2023, url

55

Bangladesh, MOLGRDC, National Urban Health Strategy, November 2014, url, p. 5

56

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2020, 2022, url, p. 18

57

Bangladesh, BBS, Statistical Yearbook Bangladesh 2021, June 2022, url, p. 45

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

21

Table 1. Administrative units of Bangladesh

58

Administrative unit

Number of units

Division

8

City Corporation

12

Municipality

330

District

64

Upazila

492

Union

4 554

Ward

40 987

Village (approx.)

87 320

Figure 2 presents the healthcare system from ward to national level and shows how it maps

onto the administrative structure. Figure 2 also shows that healthcare facilities span different

administrative levels.

59

58

Bangladesh, BBS, Statistical Yearbook Bangladesh 2021, June 2022, url, p. 45; Bangladesh, Bangladesh National

Portal, [Divisions], 25 April 2023, url; Bangladesh, Bangladesh National Portal, [Upazilla List], 25

April 2023, url; Bangladesh, Bangladesh National Portal, [Union List], 25 April 2023, url; Bangladesh,

MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2020, 2022, url, p. 18

59

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2020, 2022, url, p. 18

EUROPEAN UNION AGENCY FOR ASYLUM

22

Figure 2. Managerial hierarchy according to types of facilities from national to the ward

level, from the MOHFW, 2020

60

The National Health Care Standards establish the Quality of Care in health service delivery

including service delivery; laboratory and other diagnostic services and pharmaceutical

services; infection control and waste management; and safe and appropriate environment.

61

An ESP was developed to improve services at the Upazila level and below, and also to

complement urban primary healthcare.

62

The ESP is delivered through four tiers which are

shown in Table 2.

63

60

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2020, 2022, url, p. 29

61

Bangladesh, MOHFW, National Health Care Standards, January 2015, url, p. 12

62

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2020, 2022, url, p. 250

63

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Nutrition Population Sector Strategic Investment Plan (HNPSIP) 2016 - 2021,

February 2016, url, pp. 40-41

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

23

Table 2. The four tiers of the Essential Health Service Package, adapted from MOHFW's

Health Nutrition Population Sector Strategic Investment Plan (HNPSIP)

64

Tier

Description

1

Community Level facilities

Domiciliary Visit

Field staff (both from DGHS and Directorate General

Family Planning (DGFP)) conduct house-to-house visits

in the community to provide services to the clients in

their relevant geographical work areas.

Satellite Clinics and

Out-Reach Services

Satellite clinics (8 in each union per month) and EPI

Out-Reach Services (24 per month in each union) are

providing assigned services by Health and Family

Planning Field Workers.

Community Clinic (CC)

13 500 Community clinics have been established, one

per 6 000 population.

The Community Clinics are managed by Community

Health Care Providers (CHCP), Health Assistant (HA)

and Family Welfare Assistants (FWA).

2

Union Level Facilities (UHFWCs; Sub-Centres; and Maternal and Child Welfare

Centres (MCWCs) at union)

Union Health and Family Welfare Centres are mainly established in each Union.

Medical Doctors with additional, Family Welfare Visitors (FWVs); Sub-Assistant

Community Medical Officers (SACMO) and Pharmacists, mostly staff these Union

Level facilities.

3

Upazila Level Facilities (Health Complex (UHC) and MCWCs at Upazila)

The Upazila Health Complex is the first level referral centre in each upazila.

They include Upazila Health and Family Planning Officers (UHFPO), Resident

Medical Officers (RMO), Medical Officers (MOs), Medical Officer-MCHFP, Upazila

64

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Nutrition Population Sector Strategic Investment Plan (HNPSIP) 2016 – 2021,

February 2016, url, pp. 40-41

EUROPEAN UNION AGENCY FOR ASYLUM

24

Tier

Description

Family Planning Officers (UFPO), Specialist Doctors (Consultants); Staff Nurses;

Laboratory Technologists; and a cadre of field staff.

The Upazila Health Complexes provide both outpatient and inpatient facilities.

4

District Level Facilities (District Hospital and MCWCs at District)

District hospitals are specialised health care facilities and provide consultants from

all relevant disciplines.

The district hospitals are the secondary referral centres.

MCWCs in the districts include Maternal, Neonatal, Child and Family Planning

Services. These facilities are staffed with trained Medical Officers and FWVs.

2.1.2. Public sector

This section covers primary care for urban health services and for rural areas. It then turns to

secondary and tertiary care.

a) Urban health services – primary care

Urban health services are carried out through City Corporations and Municipalities

65

(see

Table 1) and are the responsibility of both the MOHFW and the Ministry of Local Government,

Rural Development and Co-operatives (MOLGRDC).

66

The Local Government (City

Corporation) Act

67

and the Local Government (Paurashava Act)

68

mandate that the Local

Government Division (LGD) deliver and maintain a range of services. These services include

education and basic health services (provision of preventive and promotive health as well as

limited curative care and services) and provision and the maintenance of basic services and

infrastructure for environmental sanitation.

69

The 8th Five Year Plan for Bangladesh (8FYP)

notes that primary health care is not adequate for the urban population and that it is

particularly weak for the urban poor.

70

The Bangladeshi news platform Business Standard reported in 2022 that the MOHFW has

long been interested in taking over urban health service centres, but that MOLGRDC is

65

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2019, 2020, url, pp. 162-163

66

Govindaraj, R. et al., Health and Nutrition in Urban Bangladesh, Social Determinants and Health Sector

Governance, World Bank, 2018, url, p. 61

67

Bangladesh, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh,,

[Local Government (City Corporation) Act, 2009 (Act No. 60 of 2009)], 2009, url

68

Bangladesh, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Local Government (Paurashava) Act, 2009, url

69

Govindaraj, R. et al., Health and Nutrition in Urban Bangladesh, Social Determinants and Health Sector

Governance, World Bank, 2018, url, p. 62

70

Bangladesh, GED, 8th Five Year Plan, July 2020 - June 2025, Promoting Prosperity and Fostering Inclusiveness,

December 2020, url, p. 587

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

25

reluctant to cede control. The Business Standard further noted that MOHFW acknowledges

that it intends to develop its role in urban health care.

71

A draft service outline for the ESP Urban Component is available in the Health Nutrition

Population Sector Strategic Investment Plan (HNPSIP).

72

b) Rural health services – primary care

In 2020, there were 15 954 primary healthcare facilities in Bangladesh being run by the DGHS

(see Table 3). This includes 13 948 functional Community Clinics.

73

These are sited in rural

areas and provide services to between 6 000 and 12 000 people.

74

Each Community Clinic is

staffed by Community Health Care Providers (CHCP), one Health Assistant (HA) and Family

Welfare Assistants (FWA).

75

The Community Clinics do not provide curative services, but they

provide basic levels of care in Reproductive, Maternal, New-born, Child and Adolescent

Health; Maternal Health Care; New-born and Child Health Care; Management of Child

Malnutrition; Communicable Disease Control (CDC); Non-Communicable Disease Control

(NCDC); Common Illness and Injury; Emergency Care; Common Skin, Eye, Ear and Dental

Diseases; and Behaviour Change Communication.

76

The Upazila Health Complexes range in size from 10 to 100 bed facilities (see Table 3).

77

They

provide more specialised care in the categories described above for Community Clinics.

78

Table 3 shows that outpatient services are provided at Upazila health offices, Union Sub-

centres, Union health and family welfare centres, Urban dispensaries, School health clinics

and at the Tejgaon Health Complex in Dhaka.

District hospitals, located in each of the 64 districts of the country, provide both curative,

surgical and public health services including the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI).

A draft service outline for the ESP is available in the HNPSIP.

79

71

Business Standard (The), Ministry for aiding private hospitals to cut patient bills, 21 September 2022, url

72

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Nutrition Population Sector Strategic Investment Plan, February 2016, url, pp. 52-59

73

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2020, 2022, url, p. 247

74

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2020, 2022, url, p. 248

75

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Nutrition Population Sector Strategic Investment Plan, February 2016, url, pp. 40-41

76

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Nutrition Population Sector Strategic Investment Plan, February 2016, url, pp. 52-54

77

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2019, 2020, url, p. 159

78

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Nutrition Population Sector Strategic Investment Plan, February 2016, url, pp. 52-54

79

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Nutrition Population Sector Strategic Investment Plan, February 2016, url, pp. 52-59

EUROPEAN UNION AGENCY FOR ASYLUM

26

Table 3. Primary healthcare facilities run by the DGHS, adapted from MOHFW, Health

Bulletin 2020 (December)

80

Type of facility

Type of

service

Total no. of

facilities

Total no.

beds

Community clinic (functional)

(Tier 1)*

Outpatient

Department

(OPD)

13 948

0

Other primary-level facilities

(Tier 2)*

Upazila health office

OPD

60

0

Union Sub-centre

OPD

1 312

0

Union health and family welfare centre

(UH & FWC)

OPD

87

0

Urban dispensary

OPD

35

0

School health clinic

OPD

23

0

Tejgaon Health Complex, Dhaka

1

0

Subtotal of other primary-level facilities

1 518

Upazila health complex

(Tier 3)*

100-bed

Hospital

3

300

50-bed

Hospital

345

17 250

80

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2020, 2022, url, p. 247

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

27

Type of facility

Type of

service

Total no. of

facilities

Total no.

beds

31-bed

Hospital

65

2 015

10-bed

Hospital

11

110

Subtotal of Upazila health complex

424

19 675

District Hospitals**

(Tier 3)*

50-bed

Hospital

2

100

31-bed

Hospital

7

217

30-bed

Hospital

3

90

25-bed

Hospital

1

25

20-bed

Hospital

38

760

10-bed

Hospital

13

130

Subtotal of District Hospitals

64

1 322

Grand total of primary-level facilities (not

including community clinic)

2 006

20 999

EUROPEAN UNION AGENCY FOR ASYLUM

28

Type of facility

Type of

service

Total no. of

facilities

Total no.

beds

Grand total of primary-level facilities in the

country (including community clinic)

15 954

20 999

* Tiers 1-4 are from the ESP and are defined in Table 2 above.

** District Hospitals with 50 beds and less are here counted as providers of primary care and shown as Tier 3.

c) Secondary care

Secondary care requires specialised equipment and laboratory facilities and includes

diagnosis and treatment which has to be undertaken in a hospital: it is therefore provided at

the level of District Hospital and above. The Facility Registry states that secondary care is

provided from District Hospitals, General Hospitals and 100-250 Bed Hospitals.

81

The Facility

Registry reports that there are 61 such hospitals with approved bed space for a total of

12 350.

82

Table 3, above, lists District Hospitals with 10 to 50 beds and notes that, in this

report, these are counted as providers of primary care and shown as Tier 3 in the ESP.

d) Tertiary care

Tertiary level health facilities provide advanced medical investigations and treatment. Tertiary

care is available to patients who have been referred from primary or secondary health facilities

by medical professionals and tertiary care facilities must offer specialised consultative health

care in both in-patient and outpatient departments. The Facility Registry states that tertiary

care is provided from Medical College Hospitals, Specialised Institutes and Maternity Hospitals

and that these are located at different regional levels,

83

and that in tertiary care facilities under

the DGHS, across Bangladesh, there is approved bed space for 23 076 patients.

84

2.1.3. Private sector

The economic policy of Bangladeshi governments since the 1990s has led to an increase in

for-profit, private sector health care facilities.

85

The MOHFW explains the importance of it

having a partnership-based relationship with the private sector.

86

The Bangladesh Investment

Development Authority (BIDA) describes how the private sector plays a major role in

81

Bangladesh, Government of People's Republic of Bangladesh, Facility Registry [tab for Secondary Health Care],

2023, url

82

Bangladesh, Government of People's Republic of Bangladesh, Facility Registry [Report for all District/General

Hospital], 7 March 2023, url

83

Bangladesh, Government of People's Republic of Bangladesh, Facility Registry [tab for Tertiary Health Care],

2023, url

84

Bangladesh, Government of People's Republic of Bangladesh, Facility Registry [Report for 300-500 bed Hospital

(not district hospital), Chest Disease Hospital, Dental College Hospital, Infectious Disease Hospital, Leprosy

Hospital, Medical College Hospital, Medical University, Medical University, Special Purpose Hospital, Specialized

Hospital], 7 March 2023, url

85

Bangladesh, BBS, Report on the Survey of Private Healthcare Institutions 2019, January 2021, url, p. 1

86

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Nutrition Population Sector Strategic Investment Plan, February 2016, url, p. 2

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

29

delivering healthcare services and how most tertiary healthcare institutions are run by the

private sector.

87

BIDA characterises private hospitals as being:

• large-scale multi-specialty hospitals with 250 plus beds (such as Evercare, Square,

United, Labaid, Ali Asgar Hospitals), that primarily serve affluent and upper-middle

class segments and account for around 11 % of total beds available in Dhaka;

• foundation/ non-profit hospitals which offer specialised services with discounted

pricing (such as the National Heart Foundation, Kidney Foundation, Ahsania Mission

Cancer and General Hospital); and

• general hospitals/ clinics/ nursing homes as well as private medical college hospitals.

88

A 2019 Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) survey of private sector healthcare institutions

concluded that ‘private sector healthcare institutions outnumbered the public sector

healthcare institutions by a large margin’.

89

In 2023, the Facility Registry reported 107 400

hospital beds as being available in 4 164 private hospitals

and clinics.

90

The BBS survey also determined that private sector healthcare provision is not

comprehensive. Gaps were in particular found in the provision of emergency life support,

treatment of HIV and cardiovascular conditions, and the provision of specialised cancer

therapy.

91

Private facilities that provide health care services and all pharmacies must obtain a license to

operate from MOHFW.

92

In 2017 the MOHFW issued an order to all private hospitals, clinics

and diagnostic centres regarding the renewal of licences.

93

The HNPSIP identifies the need to

tighten regulation of private secondary and tertiary care facilities.

94

In 2022, the health

research institute icddr,b reported that approximately 80 % of hospitals in Bangladesh were

private facilities and that many operated with little regulation. icddr,b describes the results of a

survey of private health facilities which it conducted, that found that 6 % of facilities surveyed

had a valid license and that 59 % were in the process of applying for a new, or renewing an

existing, license.

95

The news site bdnews24.com reported that, as of 31 August 2022, the

government had levied fines worth BDT 1.1 million [EUR 11 500] on unregistered private

medical facilities across Bangladesh.

96

87

Bangladesh, BIDA, Healthcare & Medical Device Industries, June 2021, url, p. 2

88

Bangladesh, BIDA, Healthcare & Medical Device Industries, June 2021, url, p. 3

89

Bangladesh, BBS, Report on the Survey of Private Healthcare Institutions 2019, January 2021, url, p. xxxv

90

Bangladesh, Government of People's Republic of Bangladesh, Facility Registry [Report for all Private Hospital /

Clinic], 7 March 2023, url

91

Bangladesh, BBS, Report on the Survey of Private Healthcare Institutions 2019, January 2021, url, pp. xliii-xliv

92

Govindaraj, R. et al., Health and Nutrition in Urban Bangladesh, Social Determinants and Health Sector

Governance, World Bank, 2018, url, p. 65

93

Bangladesh, MOHFW, , [Emergency Notice for Private Hospitals, clinics

and diagnostic centers], 5 September 2017, url

94

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Nutrition Population Sector Strategic Investment Plan, February 2016, url, p. 20

95

icddr,b, Licensing is the gateway to improving quality of services at private health facilities: finds an icddr,b

assessment, 30 August 2022, url

96

bdnews24.com, Bangladesh regulator orders private medical facilities to display registration details, 2

September 2022, url

EUROPEAN UNION AGENCY FOR ASYLUM

30

2.2. Healthcare resources

In 2015, the WHO characterised the health system in Bangladesh as having a shortage of

skilled health workers with twice as many doctors as nurses. Skilled health workers are

clustered in urban areas.

97

Community Clinics, the main rural facilities, are typically

understaffed and are insufficiently equipped.

98

The WHO found unqualified/semi-qualified

allopathic practitioners, such as village doctors and Community Health Workers (CHWs), to be

located mainly in rural areas. Traditional healers and trained/traditional birth attendants

practice in rural areas. Drug shop attendants are evenly distributed between urban and rural

areas.

99

An inequitable distribution of the health workforce was first reported in 1998.

100

In 2007,

Bangladesh Health Watch reported an unequal distribution and found key health providers

and qualified professionals being mainly located in urban areas and the metropolitan areas of

Dhaka, Chittagong, Rajshahi and Khulna.

101

An interviewee for this report stated that the

distribution of skilled human resources and the allocation of funding is to this day unequal: in

the divisions of Dhaka, Barisal, Mymensingh and Sylhet between 60 % and 70 % of posts for

qualified health professionals are filled, while the Chattogram, Khulna, Rajshahi and Rangpur

divisions have between 30 % and 40 % of posts filled. In addition, the skilled medical

resources are concentrated in cities rather than being spread across the divisions and

covering remote areas where demand is high.

102

In 2015, the WHO further reported that emergency transport services (ambulance) are

available in public sector facilities, but these are not in a centralized system so individual

facilities need to be contacted to access the service. The authors noted there are some for-

profit private enterprises that provide emergency transport services but that public sector

ambulance services can be poorly equipped, inoperative and can sometimes be used for

other purposes.

103

2.3. Pharmaceutical sector

Drug administration is a directorate within the MOHFW which is led by the Directorate General

of Drug Administration (DGDA).

104

The office of the DGDA is mandated to ensure quality,

97

WHO, Regional Office for the Western Pacific, Bangladesh Health System Review, 2015, url, p. 93

98

WHO, Regional Office for the Western Pacific, Bangladesh Health System Review, 2015, url, p. 92

99

WHO, Regional Office for the Western Pacific, Bangladesh Health System Review, 2015, url, p. 94

100

Ahmed, S.M. et al., The health workforce crisis in Bangladesh: shortage, inappropriate skill-mix and inequitable

distribution, 2011, url, p. 6

101

Bangladesh Health Watch, The State of Health in Bangladesh 2007: health workforce in Bangladesh, who

constitutes the healthcare system?, 2007, url, p. 24

102

Source B, interview, Dhaka, 8 February 2023. Source B is an officer in the DGHS / DGMEFW, MOHFW. The

person wishes to remain anonymous.

103

WHO, Regional Office for the Western Pacific, Bangladesh Health System Review, 2015, url p. 114

104

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2019, 2020, url, p. 9

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

31

efficacy and safety of pharmaceutical products through the implementation of relevant

legislation.

105

The main functions of the DGDA are:

• to supervise and implement the drug regulations;

• to regulate activities related to import, procurement of raw and packing materials,

production and import of finished medication, export, sale, pricing, and so on;

• to monitor and regulate the activities of all drug manufacturing companies;

• as Licensing Authority (LA), the DGDA issues licenses to manufacture, store, sell,

import and export drugs and medicines.

106

Pharmaceutical manufacturing in Bangladesh currently uses advanced technology to produce

medicines and, since 2009, Bangladeshi manufacturers have been supplying essential

medicine to all health centres in the country.

107

In 2016, Bangladesh met 97 %

108

of its domestic

demand and in 2020, this rose to 98 %.

109

BIDA reported that the industry contributed

approximately 1.8 % to the GDP.

110

Since 2016 the country has exported medical drugs to 113

countries.

111

BIDA also reported that, in 2020, Bangladesh had 271 Allopathic, 205 Ayurvedic,

271 Unani (Islamic traditional medicine), 32 Herbal and 79 Homeopathic drug producing

companies.

112

Bangladesh has had three iterations of its National Drugs Policy: the first was in 1982;

113

the

second was in 2005;

114

and the third in 2016.

115

The 2016 drug policy formulated specific

guidelines for drug safety, efficacy, logical use of drugs and effective control of drugs.

116

It

contains guidelines for production, marketing, storage and import and export of medicine.

117

A

guideline on Antimicrobial Consumption Surveillance has been issued

118

as well as a centre

and a clinical study for bioequivalence.

119

The 2016 national drug policy has established a

Pharmacovigilance System to monitor adverse drug reactions. This was examined by external

WHO assessors in July 2021 and awarded maturity level 3.

120

105

Bangladesh, MOHFW, DGDA, Quality manual, 18 May 2021, url, p. 13

106

Bangladesh, MOHFW, DGDA, Background, 6 March 2022, url

107

Bangladesh, MOHFW, [Gazette on National Drug Policy 2016], 2017, url, p. 2

108

Bangladesh, MOHFW, [Gazette on National Drug Policy 2016], 2017, url, p. 1

109

Bangladesh, BIDA, Pharmaceuticals & API Industries, December 2020, url, p. 2

110

Bangladesh, BIDA, Pharmaceuticals & API Industries, December 2020, url, p. 2

111

Bangladesh, MOHFW, [Gazette on National Drug Policy 2016], 2017, url, p. 1

112

Bangladesh, BIDA, Pharmaceuticals & API Industries, December 2020, url, p. 2

113

Bangladesh, DDA, Report of the Expert Committee for Drugs on National Drug Policy 1982, 1986, url

114

Bangladesh, MOHFW, National Drug Policy, 5 May 2005, url

115

Bangladesh, MOHFW, [Gazette on National Drug Policy 2016], 2017, url

116

Bangladesh, MOHFW, [Gazette on National Drug Policy 2016], 2017, url, p. 23

117

Bangladesh, MOHFW, [Gazette on National Drug Policy 2016], 2017, url, pp. 2-30

118

Bangladesh, MOHFW, DGDA, (Draft) Guideline on Antimicrobial Consumption Surveillance in Bangladesh, July

2022, url

119

Source A, interview, Dhaka, 8 February, 2023. Source A is an officer in the MOHFW. The person wishes to

remain anonymous.

120

Bangladesh, MOHFW, ADRM, DGDA, Pharmacovigilance Newsletter, March 2022, url, p. 5

EUROPEAN UNION AGENCY FOR ASYLUM

32

The national Essential Drugs List is set out in the 2016 policy, and it includes lists for essential

Allopathic,

121

Ayurvedic

122

and Unani

123

drugs. It covers Homeopathic Medicine

124

and Over-

The-Counter (OTC) medicines selected from commonly used Allopathic, Ayurvedic and Unani

drugs with fewer or smaller side-effects.

125

The Central Medical Store Depot (CMSD) of the

DGHS is responsible for the purchase, storage and distribution of all medical drugs to all

required places.

126

There are 219 medicines on the list, of which 117 have a fixed retail price.

127

Healthcare and pharmaceutical professionals are able to get information on available and

recent drug products from DIMS (Drug Information Management System). DIMS is a

commercial software application which can be used on mobile phones, which provides an

index of clinical drug information applicable across Bangladesh and which is currently free to

use. It provides information on available and recent drug products and is aimed at healthcare

and pharmaceutical professionals. The developers state that it is updated frequently and that

it has information on over 24 000 brand name and 1 400 generic medications.

128

DIMS

provides a database into which pharmaceutical companies can upload information about their

medications.

129

The issue of counterfeit medicines and the adverse effect they have on society has been

raised in the media.

130

An analysis of medicines collected from private drug outlets in Dhaka

city found that the majority of the samples analysed were of good quality; and that over 90 %

of the samples from the Dhaka City Corporation region were acceptable in quality and in

compliance with pharmacopoeial reference ranges.

131

The authors concluded that there is

scope for improving the storage of the ‘distributed medicines and for lowering the prices of

the medicines in the private drug outlets’.

132

The authors also noted that, during their survey,

no provider asked the buyers of the samples for a medical prescription.

133

121

Bangladesh, MOHFW, [Gazette on National Drug Policy 2016], 2017, url, pp. 24-39

122

Bangladesh, MOHFW, [Gazette on National Drug Policy 2016], 2017, url, pp. 40-41

123

Bangladesh, MOHFW, [Gazette on National Drug Policy 2016], 2017, url, pp. 42-49

124

Bangladesh, MOHFW, [Gazette on National Drug Policy 2016], 2017, url, pp. 50-57

125

Bangladesh, MOHFW, [Gazette on National Drug Policy 2016], 2017, url, pp. 58-64

126

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Central Medical Stores Depot (CMSD), url

127

Prothomalo.com, Price of 53 essential medicines set to increase, 16 July 2022, url

128

IT Medicus, Drug Information Management System (DIMS), 2022, url

129

IT Medicus, What is DIMS Gateway, 2022, url

130

New Age Bangladesh, Counterfeit medicines flood markets across Bangladesh, 25 September 2021, url; Daily

Star (The), Countering counterfeit medicine in Bangladesh, 27 February 2022, url

131

Rahman, M.S. et al., A comprehensive analysis of selected medicines collected from private drug outlets of

Dhaka city, Bangladesh in a simple random survey, 2022, url, p. 10

132

Rahman, M.S. et al., A comprehensive analysis of selected medicines collected from private drug outlets of

Dhaka city, Bangladesh in a simple random survey, 2022, url, p. 14

133

Rahman, M.S. et al., A comprehensive analysis of selected medicines collected from private drug outlets of

Dhaka city, Bangladesh in a simple random survey, 2022, url, p. 4

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

33

2.4. Patient pathways

The HNPSIP identifies a functional referral system as one of its ten key messages.

134

This

includes developing partnerships between the public sector and Alternative Medicine Care

providers and hospitals and clinics in the private sector so as to increase accessibility of

services, including in urban and rural areas that are hard to reach.

135

MOHFW recognises the

importance of referral systems that span community level facilities to national-level hospitals

and the need for Health Information Systems to enable this.

136

The Business Standard reported in 2022 that the MOHFW acknowledges that patients do not

use primary healthcare centres, but rather go directly to hospitals. MOHFW intends to expand

its role in urban health care to counteract this issue in urban areas and to reduce pressure on

secondary and tertiary healthcare facilities.

137

A functioning referral system could reportedly

halve the pressure on large tertiary hospitals.

138

This is corroborated by an interviewee for this report who stated that referrals from Upazila

Health Complexes to secondary and tertiary level healthcare do occur but, when people fall ill,

they tend to go straight to the outpatient and emergency departments of secondary and

tertiary health care.

139

In 2018, the World Bank reported that providers and services were fragmented and that there

was no coordination of the health care service delivery system in urban areas, which resulted

in a subsequent failure to provide comprehensive care. The World Bank authors found no sign

of horizontal integration, i.e., of facilities working together to provide a comprehensive range

of services to the population in their districts. They also found that the referral system lacked

vertical integration, with patients accessing specialized care directly without referrals.

140

134

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Nutrition Population Sector Strategic Investment Plan (HNPSIP), 2016 – 2021,

February 2016, url, p. 3

135

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Nutrition Population Sector Strategic Investment Plan (HNPSIP), 2016 – 2021,

February 2016, url, p. 17

136

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Health Bulletin 2020, 2022, url, pp. 317-318

137

Business Standard (The), Ministry for aiding private hospitals to cut patient bills, 21 September 2022, url

138

Daily Star (The), Patient Referral System: Still elusive after all these years, 23 January 2023, url

139

Source B, interview, Dhaka, 8 February 2023. Source B is an officer in the DGHS / DGMEFW, MOHFW. The

person wishes to remain anonymous.

140

Govindaraj, R. et al., Health and Nutrition in Urban Bangladesh, Social Determinants and Health Sector

Governance, World Bank, 2018, url, p. 70

EUROPEAN UNION AGENCY FOR ASYLUM

34

3. Economic factors

3.1. Health services provided by the State / Public

authorities

Health services provided by the State are set out in section 2.1.2. Public sector. The

Government of Bangladesh has been described as subsidising public health facilities so as to

cover the ‘bare minimum’ of the cost of care.

141

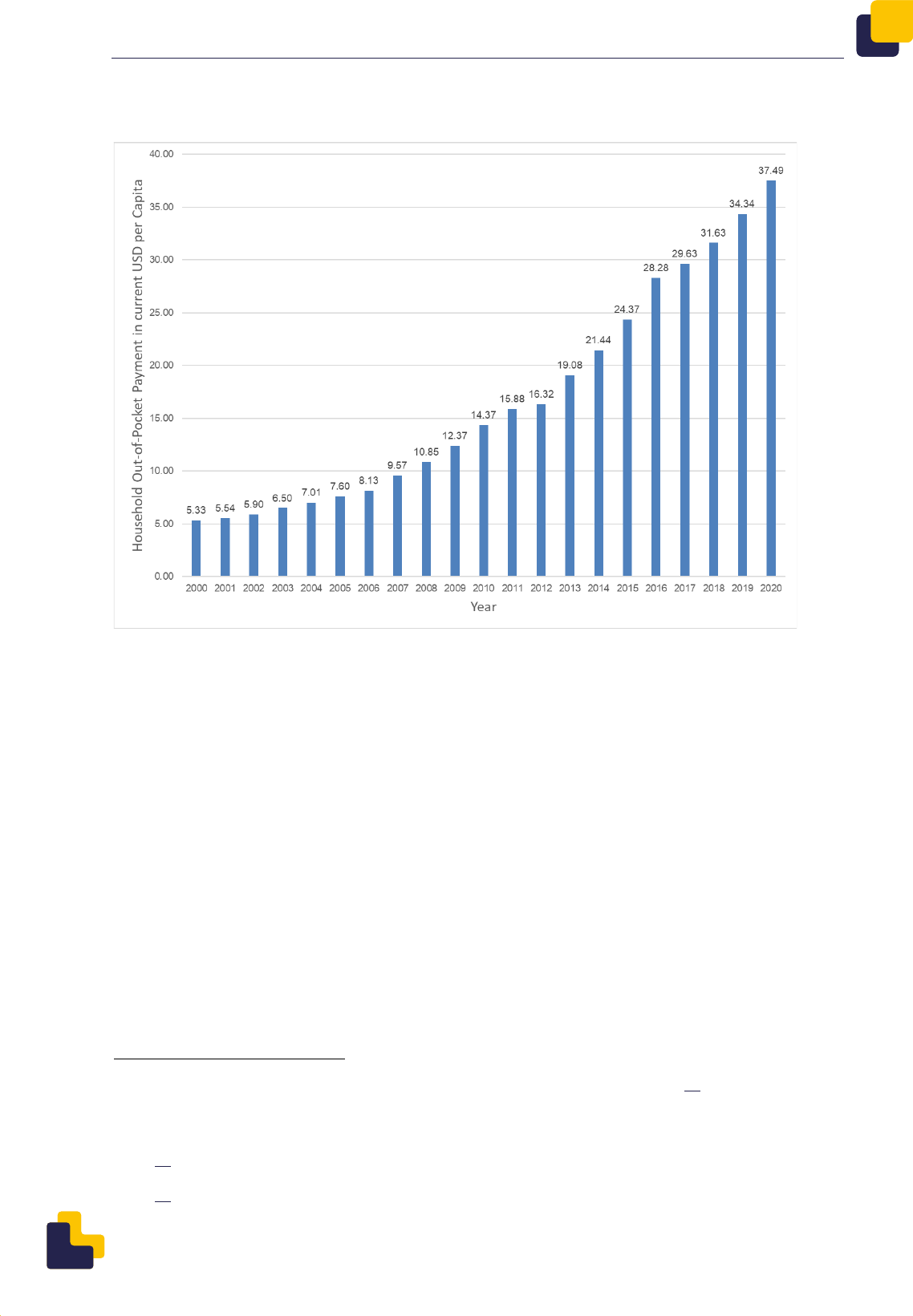

Despite an upward trend in health expenditure

shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4 below, Bangladesh continues to have the lowest per capita

expenditure on health, and the lowest expenditure as a percentage of GDP, of the 11 member

states in the WHO South East Asia Region.

142

Figure 3 shows that per capita health

expenditure by the Government increased from USD 8.62 in 2000 to USD 50.66 in 2020.

143

Figure 3. Current health expenditure per capita (current USD) - Bangladesh

144

141

Rahman, M.M., et al., Forgone healthcare and financial burden due to out-of-pocket payments in Bangladesh: a

multilevel analysis, 2022, url, p. 9

142

WHO, Current health expenditure per capita (current USD) – WHO South East Asia Region, n.d., url; WHO,

Current health expenditure as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) – WHO South East Asia Region, n.d.,

url

143

WHO, Current health expenditure per capita (current USD) - Bangladesh, n.d., url

144

WHO, Current health expenditure per capita (current USD) - Bangladesh, n.d., url. Select: Indicators, Aggregates

‘Current Health Expenditure (CHE) per Capita in US$’; Country: Bangladesh; Years 2000 to 2021; Units of

expenditure: current US$ per capita

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

35

Figure 4 shows per capita spending as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This

has risen gradually from 2.11 % in 2000 to 2.63 % in 2020.

Figure 4. Current health expenditure as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

145

3.2. Risk-pooling mechanisms

3.2.1. Public health insurance, national or state coverage

The Health Care Financing Strategy (HCFC) 2012–2032

146

aims to introduce social health

protection schemes for the poor and for formal sector employees and to move towards

provision for the entire population.

147

In principle, all citizens with an identity card have access

to public health facilities without paying a contribution. For outpatient consultation a low user

charge is required, and while medical supplies should be provided for free, it is commonly not

available in the facilities so the patients will need to supply them. OOP payments are still the

main financer for health services, through the purchase of pharmaceuticals and medical

goods.

148

In 2016, the government introduced a demand-side social health protection scheme, Shasthyo

Suroksha Karmasuchi (SSK), for the below-poverty line population in three upazilas.

149

The

145

WHO, Current health expenditure as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) - Bangladesh, n.d., url.

Select: Indicators, Aggregates ‘Current Health Expenditure (CHE) as % Gross Domestic Product (GDP)’; Country:

Bangladesh; Years 2000 to 2020; Units of expenditure: current US$ per capita

146

Bangladesh, MOHFW, Expanding Social Protection for Health: Towards Universal Coverage, Health Care

Financing Strategy 2012–2032, September 2012, url

147

Rahman, T. et al., Financial risk protection in health care in Bangladesh in the era of Universal Health Coverage,

June 2022, url, p. 13

148

WHO, Regional Office for the Western Pacific, Bangladesh Health System Review, 2015, url, pp. 66-70

149

Bonilla-Chacin, M.E. et al., Pathways to Reduce Household Out-of-Pocket Expenditure, 2020, url, p. 32

EUROPEAN UNION AGENCY FOR ASYLUM

36

scheme covers inpatient care for 70 different disease groups, with a benefit of USD 620 per

household per year.

150

SSK is in the piloting phase and while the package of benefits that it

offers is expected to evolve the efficacy of the scheme in providing protection is not yet

known.

151

3.2.2. Community-based health insurance schemes

In Bangladesh, community-based health insurance (CBHI) exists mainly as a form of micro-

health insurance initiated by NGO-microfinance institutes (NGO-MFIs), by private insurance

companies and by the state-owned corporations, the general insurer Sadharan Bima

Corporation (SBC) and the life insurer Jiban Bima Corporation (JBC).

152

Sheikh et al. categorize

CBHI based on the types of insurance providers:

‘(i) provider-based model, in which private health facilities commence health insurance and

offer healthcare from their health facilities;

(ii) microfinance-based model, where microfinance organizations manage insurance

programs for their borrowers; and

(iii) non-microfinance-based model, where NGOs launch health insurance for the organized

community or specified geographic areas without any link with microfinance’

153

People who cannot secure traditional health insurance, can obtain access to quality

healthcare via micro health insurance packages which have low premium rates. This can

decrease OOP (out-of-pocket) expenses and provide financial protection from unexpected

health care expenditures.

154

Micro-insurance for health is also designed to address spatial

exclusion from health services and cultural exclusion of women from health services.

155

In an academic study the micro-insurance sector in Bangladesh is described as not being very

effective and the authors state that work needs to be done to encourage the use of micro-

insurance products and to build trust among potential stakeholders.

156

The NGO-MFIs in Bangladesh’s microinsurance consists of national institutions such as BRAC,

Grameen Kalyan and Proshika and smaller regional-level NGOs. The national institutions

account for most of the country’s microinsurance clients while smaller regional-level NGOs

tend to offer a larger variety of microinsurance products and have a more substantial number

of policy-holders from lower revenue groups.

157

150

Ahmed, S. et al., Evaluating the implementation related challenges of Shasthyo Suroksha Karmasuchi (health

protection scheme) of the government of Bangladesh: a study protocol, 2018, url, pp. 1-2

151

Bonilla-Chacin, M.E. et al., Pathways to Reduce Household Out-of-Pocket Expenditure, 2020, url, p. 32

152

Sultana, D. et al., Evolution of Micro Insurance in Bangladesh: Financial Cushion for the Bottom of the Pyramid

Population, 2021, url

153

Sheikh, N. et al., Implementation barriers and remedial strategies for community-based health insurance in

Bangladesh: insights from national stakeholders, 2022, url, p. 2

154

BRAC, The Good Feed, Health: Healthcare made hassle-free: Micro health insurance, 12 September 2022, url

155

Werner, W.J., Micro-Insurance in Bangladesh: Risk Protection for the Poor?, August 2009, url, p. 563

156

Mamun, M., The Effectiveness of Microinsurance in Bangladesh: Can It Sustain? 2017, url, p. 14

157

Sultana, D. et al., Evolution of Micro Insurance in Bangladesh: Financial Cushion for the Bottom of the Pyramid

Population, 30 May 2021, url

HEALTHCARE PROVISION IN BANGLADESH

37

BRAC advertises two types of insurance: one with an annual premium of BDT 1 220 [EUR 13]

and one of BDT 650 [EUR 7]. Under the lower premium, BRAC states that the insured is

covered for life insurance of BDT 10 000 [EUR 105] and benefits from the following services:

• outpatient treatment of up to BDT 1 500 [EUR 16];

• hospital facility stay of up to BDT 10 000 [EUR 105];

• normal childbirth of up to BDT 2 200 [EUR 23] and

• caesarean delivery of up to BDT 6 500 [EUR 68].

158

BRAC states that a normal childbirth costs BDT 2 500 [EUR 26] at a BRAC maternity centre. In

addition, there is an admission fee of BDT 100 [EUR 1] as well as check-ups performed by a

midwife or a medical officer costing BDT 100 [EUR 1] and BDT 200 [EUR 2] respectively.

159

Micro-health insurance plans are provided by NGO-MFIs to guarantee loan repayment, as

health issues account for around one-third of all microcredit defaults.

160

Sultana et al. write that

micro-health insurance was originally a way of safeguarding a loan and the model is now used

to improve access to healthcare, especially for lower socioeconomic groups.

161

3.2.3. Private insurance companies

At the end of 2019, 32 life insurers and 45 non-life licensed insurers were in operation.

162

Insurance penetration is low with 13 million people (approximately 8 % of the population) in

Bangladesh having an insurance policy of any kind.

163

The Insurance Development and

Regulatory Authority (IDRA) states that the insurance market does not offer a diverse range of

products and notes that neither universal health insurance nor catastrophic insurance are

available. IDRA attributes this low demand to the poor reputation of the sector and to it being

complicated to there being no established practice amongst Bangladeshi households to

renew insurance policies.

164

Despite this, IDRA expresses optimism about health insurance as

a sector because middle-income groups are increasingly using, and various corporates are

offering, health insurance.

165

Since its inception, in 2010, to 2019, IDRA has approved different types of life insurance, for