CONTRACTOR PROJECT REPORT

Developing Health Equity Measures

Prepared for

the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE)

at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

by

RAND Health Care

May 2021

ii

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

The Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) advises the Secretary of the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) on policy development in health,

disability, human services, data, and science; and provides advice and analysis on economic

policy. ASPE leads special initiatives; coordinates the Department's evaluation, research,

and demonstration activities; and manages cross-Department planning activities such as

strategic planning, legislative planning, and review of regulations. Integral to this role, ASPE

conducts research and evaluation studies; develops policy analyses; and estimates the cost

and benefits of policy alternatives under consideration by the Department or Congress.

Office of Health Policy

The Office of Health Policy (HP) provides a cross-cutting policy perspective that bridges

Departmental programs, public and private sector activities, and the research community, in

order to develop, analyze, coordinate and provide leadership on health policy issues for the

Secretary. HP carries out this mission by conducting policy, economic and budget analyses,

assisting in the development and review of regulations, assisting in the development and

formulation of budgets and legislation, and assisting in survey design efforts, as well as

conducting and coordinating research, evaluation, and information dissemination on issues

relating to health policy.

ASPE Project Team

Rachael Zuckerman, Lok Samson, Wafa Tarazi, Victoria Aysola, and Oluwarantimi Adetunji

This research was funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the

Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation under Contract Number HHSP233201500038I

and carried out by RAND Health Care. Please visit https://aspe.hhs.gov/social-risk-factors-and-

medicares-value-based-purchasing-programs for more information about ASPE research on

social risk factors and Medicare's value-based purchasing programs.

iii

ASPE Executive Summary

In 2014, under the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care (IMPACT) Act, Congress asked that

ASPE study the relationship between social risk factors

1

and Medicare’s value-based

purchasing (VBP) programs. ASPE wrote two Reports to Congress, making recommendations

based on the studies’ findings. This included the recommendations that the Centers for

Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) include measures of health equity in public reporting

and VBP programs. Moreover, in the ASPE commissioned report, Systems Practices for the

Care of Socially At-Risk Populations, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and

Medicine calls out a commitment to health equity as one of six promising practices to

improve care for socially at-risk populations.

2

However, as Medicare’s VBP programs do not currently include health equity measures,

appropriate measures need to be developed and/or identified before they can be

incorporated into these programs. In response to this challenge, ASPE asked the RAND

Corporation to develop a proposed definition of health equity as a starting place and to

identify existing health equity measurement approaches that may be suitable for inclusion

in Medicare’s VBP programs, quality reporting efforts, and confidential reports. RAND

identified 10 existing approaches to health equity measurement and convened a technical

expert panel (TEP) to:

(1) provide feedback on the project team’s proposed definition of a health equity measure

and identification of features of health equity measurement approaches;

(2) develop a set of criteria for evaluating health equity measurement approaches for

potential inclusion in Medicare’s VBP programs, quality reporting efforts, and confidential

reports; and

(3) evaluate the set of health equity measurement approaches identified by the team

according to these criteria.

Based on input from RAND, ASPE, and the TEP, in this report RAND defines a health equity

measurement approach as “an approach to illustrating or summarizing the extent to which

the quality of health care provided by an organization contributes to reducing disparities in

health and health care at the population level for those patients with greater social risk

factor burden by improving the care and health of those patients.” We note that this

definition focuses on health care quality, as that was the charge from Congress under the

IMPACT Act, but measurement approaches could be considered more broadly in other

contexts.

The purpose of including health equity measurement approaches in VBP programs and

quality reporting efforts is to motivate a focus on improving health for all by reducing

disparities and to help providers prioritize particular areas for quality improvement. It could

also encourage providers to improve health equity through service enhancements, patient

engagement activities, and adoption of best practices.

Of the 10 health equity measurement approaches evaluated by the TEP (which are

described in detail in the report itself), the CMS Office of Minority Health’s (OMH) Health

Equity Summary Score (HESS) received the highest ratings from the TEP overall. This

1

The term “social risk factors” was suggested by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and

Medicine as discussed below.

2

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2016. Systems practices for the care of socially

at-risk populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

iv

approach first identified those patient experience and clinical care measures that are most

suitable for health equity comparisons. Then, the HESS assessed the extent to which care

provided through Medicare Advantage contracts was equitable based on race, ethnicity,

and dual/low-income subsidy (LIS) eligibility status. The HESS combines data across multiple

performance measures, multiple social risk factors, and multiple types of comparisons to

create a summary index of health equity.

The Biden-Harris Administration has emphasized the importance of equity across the

government, and health equity in particular. This report directly responds to Executive

Order 13985, Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through

the Federal Government, which asks all federal agencies to “identify the best methods,

consistent with applicable law, to assist agencies in assessing equity with respect to race,

ethnicity, religion, income, geography, gender identity, sexual orientation, and disability.”

3

Although this report focuses on the Medicare program, much of the findings are applicable

more broadly, including the definition of a health equity measurement approach, the

criteria that were developed for evaluating health equity measures, and the TEP’s discussion

of the measures identified.

Going forward, the health equity measures identified and evaluated in this report can

contribute to HHS implementation of Executive Order 13985 and the recommendations in

the Report to Congress on the Role of Social Risk in Medicare’s Value-Based Purchasing

Programs.

4

A Note on Social Risk Factors, Race, and Ethnicity

Although the IMPACT Act required that ASPE study “the effect of individuals’ socioeconomic

status on quality measures,” ASPE commissioned a series of reports from the National

Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine who suggested that the term “social risk

factors” was more appropriate and provided a conceptual model that listed the specific

domains and risk factors.

5

ASPE’s Reports to Congress and follow-on work, including this

report, have used the term social risk factors and the specific factors identified.

4

In more

recent years, there has been further discussion on appropriate terminology, including

understanding the distinctions between social determinants of health, social risk factors,

and social needs.

6,7

This continuing discussion shows the interconnectedness of these

concepts, while also recognizing that not all characteristics and needs can or should be

addressed in the same way.

The social risk factors identified by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and

Medicine include the domains of socioeconomic position; race, ethnicity, and cultural

context; gender; social relationships; and residential and community context. These

3

See https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/01/25/2021-01753/advancing-racial-equity-and-

support-for-underserved-communities-through-the-federal-government

4

See all of ASPE’s work on this topic at https://aspe.hhs.gov/social-risk-factors-and-medicares-value-based-

purchasing-programs

5

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2016. Accounting for social risk factors in

Medicare payment: Identifying social risk factors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

6

Alderwick, H. and Gottlieb, L.M., 2019. Meanings and misunderstandings: a social determinants of health

lexicon for health care systems. The Milbank Quarterly, 97(2), p.407.

7

Green, K. and Zook M., 2019. When Talking About Social Determinants, Precision Matters. Health Affairs

Blog, October 29. Available at https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20191025.776011/full/.

v

domains and the individual factors within them were identified based on existing evidence

of the association between the factor and worse health outcomes. We note that the factors

identified include both modifiable social determinants of health, and also additional, non-

modifiable factors such as race and ethnicity, which are themselves not causal factors for

disparities but are subject to structural inequities that produce adverse health outcomes.

The Biden-Harris Administration’s emphasis on health equity brings an additional

perspective to this issue. In addressing health equity, we in the federal government include

many of the same factors that the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and

Medicine identified as social risk factors. We take a slightly different perspective than

presented by National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine and consider non-

modifiable factors such as race, ethnicity, and rural location as associated with health

disparities, but not risk factors themselves or drivers of those disparities. We are interested

in identifying non-modifiable factors, such as race and ethnicity, to assess differential health

outcomes. We also focus on modifiable factors, such as structural racism, that are the

drivers of the outcome differences. Addressing health equity issues requires implementing

interventions to address the drivers of outcome differences and monitoring outcomes to

determine whether equity improved. Such monitoring is built on the health equity

measurement approaches evaluated in this report.

Project Report

Developing Health Equity Measures

Steven C. Martino, Sangeeta Ahluwalia, Jordan Harrison, Alice Kim, Marc N. Elliott

RAND Health Care

January 2021

Prepared for ASPE

vii

viii

Preface

Socially at-risk individuals receive lower-quality health care and experience worse

health outcomes than more advantaged individuals. One way to address this in the

Medicare population is to use Medicare’s value-based purchasing (VBP) programs,

quality reporting efforts, and confidential reports as tools to drive improvements in

quality. In particular, including health equity measurement approaches in VBP

programs and quality reporting could motivate providers to focus on reducing

disparities and to prioritize particular areas for quality improvement. It could also

encourage providers to improve health equity through service enhancements, patient

engagement activities, and adoption of best practices.

In this project, RAND Corporation researchers identified existing health equity

measurement approaches that might fit with Medicare’s VBP programs, quality

reporting efforts, and confidential reports. The project had two objectives: (1) identify

health equity measurement approaches, and (2) decide which of these approaches

merit consideration for inclusion in Medicare’s VBP programs, quality reporting efforts,

and confidential reports. This report describes the methods and findings of the project

and delineates potential first steps for the U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services to consider as it continues to evaluate the prospect of incorporating health

equity measures and domains in Medicare’s VBP and reporting programs.

This research was funded by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Evaluation and

Planning in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and carried out within

the Payment, Cost, and Coverage Program in RAND Health Care.

RAND Health Care, a division of the RAND Corporation, promotes healthier societies

by improving health care systems in the United States and other countries. We do this

by providing health care decisionmakers, practitioners, and consumers with actionable,

rigorous, objective evidence to support their most complex decisions. For more

information, see www.rand.org/health-care or contact

RAND Health Care Communications

1776 Main Street

P.O. Box 2138

Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138

(310) 393-0411, ext. 7775

RAND_Health-[email protected]

Contents

Preface ................................................................................................. Error! Bookmark not defined.ii

Contents ................................................................................................................................................................ ix

Figures ................................................................................................................................................................... xi

Ta bles ................................................................................................................................................................... xii

Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................... xiii

Summary ............................................................................................................................................................ xiv

1. Background and Purpose ........................................................................................................................... 1

!"#$%&'()* ...................................................................................................................................................... 1

+&',-#./ 01,-#.23-4 ........................................................................................................................................... 2

2. Literature Review Methods and Results ............................................................................................. 4

Definition of a Health Equity Measurement Approach to Assess Organizational

Contributions ........................................................................................................................................... 4

Search Strategy .............................................................................................................................................. 4

562%21262.7/ 8&2.-&2" .......................................................................................................................................... 5

9&.2#6-:;-<'&. /=#&--)2)% ............................................................................................................................ 5

3. Detailed Information on Identified Approaches ........................................................................... 12

Measurement Framework for Evaluating How Well an Organization Meets National

CLAS Standards (HHS OMH) .......................................................................................................... 12

NQF Disparities-Sensitive Measure Assessment .......................................................................... 14

AHRQ >".2')"6/ ?-"6.@#"&-/ A("62.7/ ")* /B24<"&2.2-4 /;-<'&. ...................................................... 16

CM S OMH Mapping Medicare Disparities Tool ............................................................................. 18

CMS OMH Reporting of CAHPS and HEDIS Data Stratified by Race and Ethnicity for

Medicare Beneficiaries ..................................................................................................................... 19

C2))-4'." /?-"6.@#"&-/ B24<"&2.2-4 /;-<'&. ......................................................................................... 20

CMS Assessment of Hospital Disparities for Dual-Eligible Patients ..................................... 22

CMS OMH Health Equity Summary Score ........................................................................................ 24

Zimmerman Health-Related Quality of Life Approach to Assessing Health Equity ...... 27

Zimmerman and Anderson Approach to Evaluating Trends over Time in Health

Equity ....................................................................................................................................................... 28

4. Summary of Identified Health Equity Measurement Approaches ........................................ 29

5. Technical Expert Panel Process and Members .............................................................................. 33

6. TEP Input on Project Framing and Approach ................................................................................ 34

Inp ut on Definition of a Health Equity Measurement Approach ........................................... 34

Input on Premise of the Project ........................................................................................................... 35

Input on Evaluation Criteria .................................................................................................................. 35

7. Detailed Assessment of Identified Approaches ............................................................................. 38

Measurement Framework for Evaluating How Well an Organization Meets National

CLAS Standards .................................................................................................................................... 38

NQF Disparities-Sensitive Measure Assessment .......................................................................... 41

9?;A />".2')"6 /?-"6.@#"&-/ A("62.7/ ")* /B24<"&2.2-4 /;-<'&. ....................................................... 42

CM S OMH Mapping Medicare Disparities Tool ............................................................................. 44

CMS OMH Reporting of CAHPS and HEDIS Data, Stratified by Race and Ethnicity, for

Medicare Beneficiaries ..................................................................................................................... 46

C2))-4'." /?-"6.@#"&-/ B24<"&2.2-4 /;-<'&. ......................................................................................... 48

CMS Assessment of Hospital Disparities for Dual-Eligible Patients ..................................... 50

ix

CMS OMH Health Equity Summary Score ........................................................................................ 52

Zimmerman Health-Related Quality of Life Approach to Assessing Health Equity ...... 54

Zimmerman and Anderson Approach to Evaluating Trends over Time in Health

Equity ....................................................................................................................................................... 56

8. Summary and Key Takeaways .............................................................................................................. 59

=(DD"&7 ........................................................................................................................................................ 59

E-7/ F"$-"G"74 ............................................................................................................................................. 60

Appendix A. Ambulatory, Hospital, Behavioral Health, and Public Health Measures

Identified as Part of the Measurement Framework for Evaluating How Well an

Organization Meets National CLAS Standards (HHS OMH) ................................................... 62

Appendix B. Measures Identified as Disparities-Sensitive According to the NQF

Disparities-Sensitive Measure Assessment .................................................................................. 64

Appendix C. Biographical Information on Expert Panelists ......................................................... 67

x

Figures

Figure 2. 1. Literature Review F low Diagram ...................................................................................... 10

Figure 3.1. NQF Disparities-Sensitive Measure Identification................................ ..................... 15

Figure 4.2. Components of the HESS ....................................................................................................... 26

Figure 4.3. HESS: Blending Scheme ......................................................................................................... 26

xi

Tables

Ta ble S.1. Ten Identified Approaches to Health Equity Measurement ................................... xix

Ta ble 2.1. Database Search Strategy ......................................................................................................... 7

Table 2.2. Summary of the Health Equity Measurement Approaches Identified by the

Literature Review .................................................................................................................................. 11

Table 3.1. Cross-Cutting Measures to Evaluate How Well an Organization Meets National

CLAS Standards ...................................................................................................................................... 13

Ta ble 4.1. Summary of Identified Approaches to Health Equity Measurement ................... 32

Table 7.1. TEP Ratings of Measurement Framework for Evaluating How Well an

Organization Meets National CLAS Standards .......................................................................... 40

Table 7.2. TEP Ratings of NQF Disparities-Sensitive Measure Assessment .......................... 42

Table 7.3. TEP Ratings of 9?;A/ >".2')"6/ ?-"6.@#"&-/ A("62.7/ ")*/ B24<"&2.2-4/ ;-<'&. ....... 44

Table 7.4. TEP Rat ings of CMS O MH Mapping Medicare Disparities Tool .............................. 46

Table 7.5. TEP Ratings of CMS OMH Reporting of CAHPS and HEDIS Data Stratified by

Race and Ethnicity for Medicare Beneficiaries ......................................................................... 48

Ta ble 7.6. TEP Ratings of Minnesota Healthcare Di sparities Report ........................................ 50

Table 7.7. TEP Ratings of CMS Assessment of Hospital Disparities for Dual-Eligible

Patients ...................................................................................................................................................... 52

Table 7.8. TEP Ratin gs of CMS OMH Health Equity Summary Score ........................................ 54

Table 7.9. TEP Ratings of Zimmerman Health-Related Quality of Life Approach to

Assessing Health Equity ..................................................................................................................... 56

Table 7.10. TEP Ratings of Zimmerman and Anderson Approach to Evaluating Trends

over Time in Health Equity ............................................................................................................... 58

xii

Abbreviations

AAC average annual change

AHRQ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

ASPE Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

CAHPS Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems

CINAHL Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

CLAS Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services

CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Se rvices

FFS fee- for -service

HEDIS Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set

HESS Health Equity Summary Score

HHS U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

LIS Low -Income Subsidy

MA Medicare Advantage

MeSH Medical Subject Headings

MMD Mapping Me dicare D isparities

NQF National Quality Forum

OMH Office o f Mi nority Health

PDP prescription drug plan

RSRR risk -standardized readmission rate

TEP technical expert p anel

VBP value- based purchasing

xiii

- -

-

-

-

xiv

Summary

There is growing recognition that social risk factors

8

—such as income, education, race

and ethnicity, and community resources—play a major role in health.

9

Despite ongoing

efforts to address inequities, evidence suggests that socially at-risk individuals receive

lower-quality health care and experience worse health outcomes than more-advantaged

individuals. Medicare’s value-based purchasing (VBP) programs, quality reporting

efforts, and confidential reports to providers of their performance on quality measures

could be powerful tools to drive improvements in the quality of care provided to

socially at-risk individuals. In particular, including health equity measurement

approaches in VBP programs and quality reporting efforts could motivate a focus on

reducing disparities and help providers prioritize particular areas for quality

improvement. It could also encourage providers to improve health equity through

service enhancements, patient engagement activities, and adoption of best practices.

Toward that end, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

(ASPE) asked the RAND Corporation to identify existing health equity measurement

approaches that may be suitable for inclusion in Medicare’s VBP programs, quality

reporting efforts, and confidential reports. This project had two objectives: (1) identify

health equity measurement approaches, and (2) decide which of these approaches

merit consideration for inclusion in Medicare’s VBP programs, quality reporting efforts,

and confidential reports. To meet these objectives, the project team conducted a

literature review to identify health equity measurement approaches developed or used

for the purpose of systematic performance assessment and convened a technical expert

panel (TEP) to consider the use of these health equity measurement approaches in VBP

programs, quality reporting efforts, and confidential reports. The project team

synthesized feedback from the TEP to identify the most promising health equity

measurement approaches and inform the U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services (HHS) about which approaches could be incorporated in Medicare’s VBP

programs, quality reporting efforts, and confidential reports.

A formal definition of a health equity measurement approach was developed to

define the scope of the literature search and help specify the TEP’s evaluation of the

identified approaches. The definition, which was first developed iteratively by RAND

and ASPE and then further shaped by the TEP, is as follows: an approach to illustrating

or summarizing the extent to which the quality of health care provided by an

organization contributes to reducing disparities in health and health care at the

8

Though many people use the term social risk factor to refer to mechanisms that foster inequities in

health or health care—e.g., food insecurity or language barriers—we use the term here to refer to groups

that tend to bear a disproportionate share of social risk factor burden, e.g., racial and ethnic minorities. In

that sense, we are conceptualizing group membership as a proxy for social risk factors. By using the term

social risk factor to refer to membership in certain groups, we do not mean to imply that risk or

disadvantage is inherent in people, homogeneous within groupings (e.g., a particular race) or across

geography, or immutable over time. Rather, it is the result of past and present inequities in our society.

9

National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, Accounting for Social Risk Factors in Medicare

Payment: Identifying Social Risk Factors, Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2016; United States

Department of Health and Human Services, “Healthy People 2020: Social Determinants of Health,”

webpage, 2014. As of May 11, 2020: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-

objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health

xv

population level for those patients with greater social risk factor burden by improving

the care and health of those patients.

Ten such approaches were identified. These ten approaches fit within three broad

categories of approaches: (1) approaches focused on determining which existing

quality measures are suitable for health equity comparisons (i.e., permit reliable and

valid comparisons among social risk factor groups) or for measuring organizational

structures, systems, and processes hypothesized to promote the delivery of high-quality

care for all; (2) approaches that engaged in particular kinds of comparisons of measures

(not necessarily statistical comparisons), on a measure-by-measure basis, between

groups of patients with greater versus lesser social risk factor burden; and (3)

approaches that developed a system for combining different dimensions of health

equity into a single summary index. Table S.1 lists these ten approaches and provides

summary information about them, including whether the approach focused on measure

identification (Category 1), measure-by-measure comparisons (Category 2), or creating

a summary index (Category 3).

This project also identified a set of guidelines for health equity measurement. A

health equity measurement approach should, ideally,

• be based on measures on which disparities in care are known to exist for certain

populations or that address health care disparities and culturally appropriate

care

• reflect available evidence on the relationship between a social risk factor and

health or health care outcome

• be designed to incentivize achievement or improvement for at-risk beneficiaries,

including having a valid and appropriate benchmark and/or reference group if

comparisons to benchmarks and/or reference groups are made

• include design features that guard against unintended consequences of

worsening quality or access or disincentivizing resources for any beneficiaries,

including the at-risk beneficiaries who are the focus of health equity

measurement

• establish measurability requirements that ensure the ability to make reliable

distinctions between health care providers in their performance in the domain of

health equity

• capture information about small subgroups where possible while limiting the

influence of imprecise estimates of provider performance.

In the case of a summary index, the measure should additionally

• summarize information in a way that is psychometrically sound

• allow for disaggregation of information to permit easy identification of quality

improvement targets.

Two of the identified approaches—the Measurement Framework for Evaluating

Organizational Compliance with Standards for National Culturally and Linguistically

Appropriate Services (CLAS) and the National Quality Forum’s (NQF) Disparities-

Sensitive Measure Assessment—determined whether existing quality measures were

suitable for health equity comparisons or for measuring organizational structures,

systems, and processes hypothesized to promote delivery of high-quality care for all

(Category 1).

Two approaches—the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) National

Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report and the Mapping Medicare Disparities (MMD)

xvi

Tool developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Office of Minority

Health (CMS OMH)—focused on performance comparisons by social risk-factor groups

either nationally or at a smaller geographical unit. Each of these two approaches

included a broad array of measures, treating each measure separately (the hallmark of

Category 2), though only the AHRQ approach involved statistical comparisons.

Two approaches—the CMS OMH stratified reporting of Medicare Advantage (MA),

prescription drug plan (PDP), and Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) performance data by

beneficiary race and ethnicity and the Minnesota Healthcare Disparities Report—

involved stratified reporting of data on patient experience and/or clinical care by social

risk factors with statistical comparisons to benchmarks. The CMS Office of Minority

Health’s approach involved reporting performance at the level of MA contracts, PDP

contracts, and states (for Medicare FFS), and the Minnesota Healthcare Disparities

Report involved reporting performance both statewide and at the level of individual

medical groups. Under these approaches, comparison of performance by contract, state,

or medical group was done on a measure-by-measure basis (Category 2).

The CMS Assessment of Hospital Disparities for Dual-Eligible Patients involved two

complementary methods for assessing hospital performance in the realm of health

equity. The Within-Hospital Disparity Method was used to measure the difference in a

health outcome between patients who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid

(referred to as dual-eligible patients)

10

and patients who are not dually eligible within a

hospital. The Dual Eligible Outcome Method was used to compare performance for dual-

eligible patients across hospitals. In each case, the outcome measure of interest was 30-

day all-cause unplanned readmission following hospitalization for pneumonia. Because

this approach involved only one social risk factor and one outcome measure and the

two types of comparisons were kept separate, it fits within Category 2.

Two approaches were identified within Category 3. The CMS OMH’s Health Equity

Summary Score (HESS) approach identified patient experience and clinical care

measures specifically suitable for health equity comparisons and used data on those

measures to assess the extent to which care provided through MA contracts was

equitable based on race and ethnicity as well as dual/low-income subsidy (LIS)

eligibility status. The HESS combined data across multiple performance measures,

multiple social risk factors, and multiple types of comparisons, i.e., both within- and

between-provider comparisons and comparisons focused on both cross-sectional

performance and improvement in performance to create a summary index of health

equity (Category 3).

Zimmerman’s Health-Related Quality of Life Approach to Measuring Health Equity

synthesized information across multiple measures (Category 3). Zimmerman’s measure

is oriented toward assessing the total deviation from a defined privileged group and

allows disaggregation from the national level to the level of states and smaller

geographic areas. Zimmerman and Anderson developed a related approach that

generates trend information to characterize disparities in self-rated health and healthy

days in the past month as either decreasing, increasing, or not changing (this approach

involved both Category 2 and Category 3 assessments).

Of approaches focused on measure identification (Category 1), the NQF Disparities-

Sensitive Measure Assessment was viewed most favorably by the TEP. Using a set of

carefully established criteria and an easy-to-understand point system, this approach

10

The demonstration of this approach focused on full dual-eligible beneficiaries aged 65 and older.

xvii

identified 76 existing NQF-endorsed measures as disparities-sensitive.

11

Although

considerable work would be needed to determine whether and how these measures

could be linked to social risk data and whether and how valid comparisons could be

made, this approach was viewed as a valuable initial step toward measuring health

equity and disparities in health care quality. It is potentially applicable to any Medicare

VBP or quality reporting program that collects one or more of the disparities-sensitive

measures.

Of approaches focused on measure-by-measure comparisons (Category 2), the

approach underlying the Minnesota Healthcare Disparities Report was judged

most favorably by the TEP. The perceived advantages of this approach include its

thoughtfully chosen group of measures, incorporation of multiple important social risk

factors (i.e., race, ethnicity, preferred language, and country of origin), ability to reliably

distinguish performance among providers, clear focus on incentivizing achievement for

at-risk beneficiaries, and choice to anchor disparities to the overall state average rather

than the performance of a predetermined group. Although some additional work would

be needed to transfer this approach to a broader setting, including making careful

considerations about sample sizes required for accurate comparisons and determining

the availability of data on social risk factors, the method itself is readily applicable to all

Medicare VBP and quality reporting programs.

Of approaches focused on summary indices (Category 3), the CMS OMH HESS was

judged most favorably by the TEP. The perceived advantages of this approach include

its joint consideration of cross-sectional performance and improvement in

performance, focus on patient experience and clinical quality, careful attention to

reliability and the sample size required to achieve it, direct applicability to certain VBP

and quality reporting programs, and transferability to other programs. CMS is currently

developing a dashboard to provide confidential HESS data to MA contracts in the near

future. Scores on this metric could potentially be incorporated into the Medicare Plan

Finder and the MA Quality Star Ratings Program. This approach could easily be

extended to other social risk factors and measures, and there are plans to test the

feasibility of extending this approach to settings beyond MA.

Of the ten approaches evaluated, the HESS received the highest ratings from the TEP

overall. Given the high ratings it received, the HESS may be closest to meeting the full

scope of goals outlined by ASPE for incorporating a measure of health equity into a

Medicare VBP or quality reporting program. If HHS were to move forward with this

approach, it could consider possible refinements to the approach based on the practices

established by the NQF Disparities-Sensitive Measure Assessment and the Minnesota

Healthcare Disparities Report and the guidelines for health equity measurement

outlined by the TEP. Several of the measures that are included in the HESS are among

the 76 measures identified as disparities-sensitive by NQF. It might be possible to

include in the HESS additional measures from the set identified by NQF, provided that

the measures are collected for MA plans and meet the reliability and sample size

requirements established for the HESS. The analyses that underlie the Minnesota

Disparities Report are similar to the analyses that underlie the cross-sectional

component of the HESS. In the Minnesota Healthcare Disparities Report, plan

11

Disparities-sensitive measures were defined as measures of conditions that are prevalent among at-risk

groups, measures assessing a high-impact aspect of health care (i.e., conditions affecting large numbers of

people, leading causes of morbidity and mortality, conditions leading to high resource use, and severe

illnesses), measures on which a substantial disparity has been identified, and measures that map to an

NQF-endorsed communication-sensitive practice for care coordination or cultural competency.

xviii

performance by patients’ preferred language and country of origin are considered in

addition to race and ethnicity. Information on country of origin is not available for MA

beneficiaries, but information about Spanish preference is available. Thus, Spanish

preference could be considered as a possible third social risk factor for the HESS.

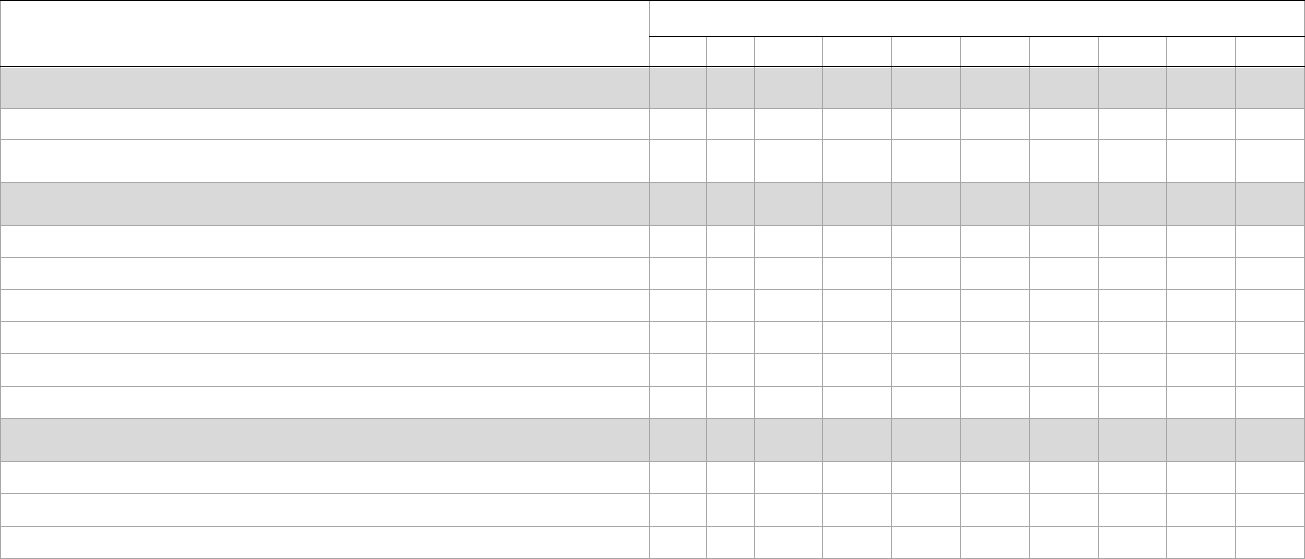

Table S.1. Ten Identified Approaches to Health Equity Measurement

Measurement Approach Setting/Population Social Risk Factor(s) Focus

1. Measurement Framework for Evaluating How Well an Health care organizations Race/ethnicity; limited English Measure identification

Organization Meets National Standards for Culturally proficiency; low literacy

and Linguistically Appropriate Services (HHS OMH)

2. NQF Disparities-Sensitive Measure Assessment Cross-cutting Race/ethnicity Measure identification

3. AHRQ National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Overall U.S. population Age; sex, race/ethnicity Measure-by-measure

Report comparisons

4. CMS OMH Mapping Medicare Disparities Tool Medicare FFS Race/ethnicity; dual eligibility; Measure-by-measure

sex; age comparisons

5. CMS OMH Reporting of CAHPS and HEDIS Data by MA and prescription drug Race/ethnicity Measure-by-measure

Race/Ethnicity for Medicare Beneficiaries plans, Medicare FFS comparisons

6. Minnesota Healthcare Disparities Report Minnesota health plan Race, ethnicity, preferred Measure-by-measure

enrollees language, country of origin comparisons

7. CMS Assessment of Hospital Disparities for Dual- Hospitals Dual eligibility Measure-by-measure

Eligible Patients comparisons

8. CMS OMH Health Equity Summary Score Medicare Advantage plans Race/ethnicity; dual eligibility Summary index

9. Zimmerman Health-Related Quality of Life Approach to General adult U.S. population Race/ethnicity; sex; income Summary index

Assessing Health Equity

10. Zimmerman and Anderson Approach to Evaluating General adult U.S. population Race/ethnicity; sex; income Measure-by-measure

Trends over Time in Health Equity comparisons; summary index

NOTE: CAHPS = Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems; CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; HHS = U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services; FFS = fee-for-service; HEDIS = Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set; MA = Medicare Advantage; NQF = National

Quality Forum; OMH = Office of Minority Health.

xix

1

1. Background and Purpose

Background

There is growing recognition that social risk factors

12

—such as income, education, race and

ethnicity, and community resources—play a major role in health.

13

Despite ongoing efforts

to address inequities, evidence suggests that socially at-risk individuals receive lower-

quality health care and experience worse health outcomes than more-advantaged

individuals.

14

Medicare’s value-based purchasing (VBP) programs, which link reimbursement to the

quality and efficiency of health care delivered, could be a powerful tool to drive

improvements in the quality of care provided to patients with social risk factors, which

could potentially improve health outcomes among patients with social risk factors and

reduce health disparities. Medicare’s VBP programs include pay-for-performance programs

in each health care setting that reward providers on quality and cost, as well as Alternative

Payment Models, such as Accountable Care Organizations, or state population–based

models in which providers are at financial risk for lowering costs and improving quality of

care. The scope of this report is focused mainly on pay-for-performance programs. Quality

reporting efforts and confidential reports to providers may have similar incentivizing

effects. The National Academy of Medicine identified the following social risk factors as

likely to be important to health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries: socioeconomic

position; race, ethnicity, and cultural context; gender; social relationships; and residential

and community context.

15

Including health equity measurement approaches in VBP and

quality reporting programs could motivate a focus on reducing disparities and help

providers prioritize particular areas for quality improvement activities. It could also

encourage providers to address health equity through service enhancements, patient

12

Though many people use the term social risk factor to refer to mechanisms that foster inequities in health

or health care—e.g., food insecurity or language barriers—we use the term here to refer to groups that tend

to bear a disproportionate share of social risk factor burden, e.g., racial and ethnic minorities. In that sense,

we are conceptualizing group membership as a proxy for social risk factors. By using the term social risk

factor to refer to membership in certain groups, we do not mean to imply that risk or disadvantage is inherent

in people, homogeneous within groupings (e.g., a particular race) or across geography, or immutable over

time. Rather, it is the result of past and present inequities in our society.

13

National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, Accounting for Social Risk Factors in Medicare

Payment: Identifying Social Risk Factors, Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2016; U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), “Healthy People 2020: Social Determinants of Health,”

webpage, 2014. As of May 11, 2020: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-

determinants-of-health

14

Institute of Medicine, How Far Have We Come in Reducing Health Disparities? Progress Since 2000:

Workshop Summary, Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. 2012.

15

Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Social Risk Factors and Performance Under Medicare’s

Value-Based Purchasing Programs, Washington, D.C.: HHS, 2016; National Academies of Science, Engineering,

and Medicine, Accounting for Social Risk Factors in Medicare Payment: Identifying Social Risk Factors,

Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2016.

2

engagement activities, and adoption of best practices to improve performance in the health

equity domain. The use of health equity measurement approaches as part of VBP and

quality reporting sends a strong signal that health equity is an important component of

delivery system transformation.

However, if beneficiaries with social risk factors have worse outcomes because of elements

beyond the control of health care providers, the inclusion of health equity measurement

approaches in VBP and quality reporting programs could make providers reluctant to care

for beneficiaries with social risk factors, out of fear of incurring penalties, not achieving

bonuses, or having their reputations damaged due to factors they have limited ability to

influence.

In 2014, under the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Act, Congress asked that the

Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) study the relationship between

social risk factors and Medicare’s VBP programs. ASPE wrote two Reports to Congress

(referred to as Study A and Study B), making recommendations based on the study’s

findings. These reports outline multiple strategies for accounting for social risk factors in

Medicare’s VBP programs.

17

Although the reports recommend including health equity

measures in Medicare’s VBP programs, they do so cautiously, outlining several

considerations that need to be addressed first. For example, the reports stress that the

design of any such measurement approach needs to be informed by careful consideration

of the linkage between social risk factors and the outcome or outcomes measured. They

also highlight the need to consider whether score adjustments are needed to account for

factors outside the control of providers. Steps such as these ensure that health equity

measurement approaches can be used in VBP programs to incentivize improvements for

beneficiaries with social risk factors while guarding against any real or perceived

disincentives to care for these beneficiaries.

16

Project Objectives

ASPE asked the RAND Corporation to identify existing health equity measurement

approaches that may be suitable for inclusion in Medicare’s VBP programs, quality

rep

orting efforts, and confidential reports. This project had two objectives:

1. Identify and describe health equity measurement approaches.

2. Decide which of these merit consideration for inclusion in Medicare’s VBP

programs, quality reporting efforts, and confidential reports.

In August 2020, the project team conducted a literature review to identify health equity

measurement approaches developed or used for the purpose of systematic performance

assessment. In September 2020, the project team convened a technical expert panel (TEP)

with experts on social risk factors, health disparities, health equity, quality measurement,

and Medicare’s VBP programs and quality reporting efforts to consider the use of these

16

113

th

Congress of the United States, “H.R.4994 - IMPACT Act of 2014,” webpage, 2014. As of January 11,

2021: https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/4994

17

ASPE, Social Risk Factors and Performance Under Medicare’s Value-Based Purchasing Programs, Washington,

D.C.: HHS, 2016; ASPE, Social Risk Factors and Performance Under Medicare’s Value-Based Purchasing

Programs, Washington, D.C.: HHS, 2020.

3

health equity measurement approaches in VBP programs, quality reporting efforts, and

confidential reports.

The objectives of the TEP were to (1) provide feedback on the project team’s proposed

definition of a health equity measure and identification of features of health equity

measurement approaches; (2) reach consensus on a set of criteria for evaluating health

equity measurement approaches for potential inclusion in Medicare’s VBP programs,

quality reporting efforts, and confidential reports; and (3) evaluate the set of health equity

measurement approaches identified by the team according to these criteria.

The project team synthesized feedback from the TEP to identify the most promising health

equity measurement approaches in development and inform potential next steps toward

incorporating health equity measures and domains in Medicare’s VBP programs, quality

reporting efforts, and confidential reports.

The rest of this report is organized as follows. Chapter 2 describes the literature review

methods and results. Chapter 3 provides detailed information on each of the identified

health equity measurement approaches, and Chapter 4 provides an integrative summary of

these approaches. Chapter 5 provides information about how the TEP was convened and

conducted. Chapter 6 describes the input provided by the TEP on the project framing and

approach. Chapter 7 describes TEP members’ assessment of and commentary on each of

the identified health equity measurement approaches. Chapter 8 provides a summary of

the findings of this project and key takeaways for the U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services (HHS).

4

2. Literature Review Methods and Results

The project team conducted a review of articles and reports on health equity measurement

approaches developed or intended for use in systematic performance assessment.

Definition of a Health Equity Measurement Approach to Assess

Organizational Contributions

We developed a formal definition of a health equity measure to guide our search. The

definition, which emphasizes performance assessment, is as follows: an approach to

illustrating or summarizing the extent to which the quality of health care provided by an

organization contributes to reducing disparities in health and health care at the population

level for those patients with greater social risk factor burden by improving the care and

health of those patients.

18

Though such an approach is not centered on performance

assessment per se, we agreed that an approach focused on structural measures—measures

of the extent to which structures, systems, or processes hypothesized to promote the

delivery of equitable care are in place within a health care organization—was in scope,

given that such measures capture potentially important mechanisms for aligning care and

resources with physical, mental, and social needs to optimize health outcomes for all.

Search Strategy

Our search strategy included three approaches. First, we used a structured database search

on Ovid MEDLINE and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

to identify English-language, peer-reviewed articles published from January 2010 to

August 2020. We identified articles using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords

with at least (1) one health equity or social risk keyword and (2) one performance

measurement keyword. Table 2.1 lists the search terms by category. Second, we used a

purposive “snowball” approach to identify potentially relevant documents by reference-

mining seminal reports (see List 2.1). These are reports that were identified or suggested

by health equity measurement experts within the project team and at ASPE. Third, we

conducted a gray literature search to identify relevant documents from websites of federal

agencies (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] and ASPE), the National

Academy of Medicine, the National Quality Forum (NQF) Quality Positioning System, and

the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse. After removing duplicates, our search

yielded 783 records, including both published peer-reviewed journal articles and gray

literature reports (Figure 2.1).

18

The National Academy of Medicine (2016) identified five social risk factors that are conceptually likely to

be of importance to health outcomes of Medicare beneficiaries: socioeconomic position; race, ethnicity, and

cultural context; gender; social relationships; and residential and community context.

5

Eligibility Criteria

Because our aim was to identify health equity measurement approaches, we sought to

exclude articles and reports if they (1) did not describe a specific health equity

measurement approach developed or used for the purpose of systematic performance

assessment; or (2) were focused on risk adjustment. These exclusions were applied during

the article/report screening process described next.

Article/Report Screening

Figure 2.1 illustrates the article/report screening process. We first reviewed titles and

abstracts of the 783 documents we identified. To ensure consistent application of our

eligibility criteria, three reviewers first independently coded 60 articles across three

separate rounds (i.e., 20 articles in each round). Between rounds, reviewers met to discuss

independent review outcomes and discrepancies and their application of the criteria, as

well as to further refine the definition of each criterion. Disagreements were resolved

through discussion or by involving the principal investigator until consensus was reached.

Subsequent titles/abstracts were divided, and each was reviewed by one of the three

reviewers. Any uncertainties were discussed by the project team together, and all abstracts

marked for inclusion were also reviewed by the project team before proceeding to full-text

review. We excluded 647 documents at the title/abstract stage that did not meet eligibility

criteria.

We then undertook a full text review of 136 documents to identify measurement

approaches that would allow health plans or providers to identify areas in which they are

performing well or poorly at providing high-quality care to patients with greater social risk

factor burden.

Upon full text review, we applied additional exclusions, with the aim of excluding

documents that did not articulate a specific health equity measurement approach.

Specifically, we excluded (a) documents that described theoretical approaches or

frameworks to health equity measurement not currently in development or in use; (b)

documents that proposed adjustments to scores or adjustments to payment allocations

within an incentive scheme; (c) documents that simply detailed the existence of disparities

without the use of a specific measure of disparity; and (d) documents that described the

effect of an incentive scheme on disparities. At this stage, we excluded an additional 114

documents that did not meet the eligibility criteria.

Of the 22 documents that met our eligibility criteria, eight fit the fifth category of

measurement approaches described above (i.e., measures of the extent to which structures,

systems, or processes hypothesized to promote the delivery of equitable care are in place

within a health care organization). Because these eight documents all described similar

approaches, we opted to include only the most comprehensive of them in our final results.

The document that was kept describes a measurement framework for evaluating how well

health care organizations comply with national standards for providing culturally and

6

linguistically appropriate services. This document was authored by Davis et al.

19

and

describes the results of research commissioned by HHS’s Office of Minority Health (HHS

OMH). The seven documents that we did not include in our final results are in List 2.2.

Similarly, four of the 22 documents that met our eligibility criteria were reports of national

disparities on patient experience, clinical process and outcome, and patient safety

measures. Because these four reports all describe similar approaches to the analysis of

disparities, we opted to include just one in our final results. The report that was included is

the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) National Healthcare Quality and

Disparities Report.

20

The three documents that we did not include in our final results are

also in List 2.2. Thus, a total of 11 articles/reports were selected for inclusion in our final

results. One of the 11 articles/reports selected for inclusion

21

describes the analytic

foundation underlying another of the reports.

22

Thus, although 11 articles/reports were

identified, they pertain to only ten total approaches (see Table 2.4 for a summary).

In the following chapters, we describe in detail the ten approaches to health equity

measurement described in each of these 11 articles/reports. The description includes

information about the approach, the setting and population in which the approach was

initially evaluated (if applicable), the social risk factors encompassed by the approach, the

outcome measures that factor into the approach, and any available psychometric

information reported in the article/report. The description also indicates the features of

the approach (see Features of Health Equity Measurement Approaches above) and whether

the approach has been endorsed by a measure endorsement body or is currently in use in a

Medicare VBP or quality reporting program.

19

L. M. Davis, L. T. Martin, A. Fremont, R. Weech-Maldonado, M. V. Williams, and A. Kim, Development of a

Long-Term Evaluation Framework for the National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate

Services (CLAS) in Health and Health Care, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, EP-68215, 2018.

20

AHRQ, 2018 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report, Rockville, Md., 2019. As of January 4, 2021:

https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr18/index.html

21

S. C. Martino, R. M. Weinick, D. E. Kanouse, J. A. Brown, A. M. Haviland, E. Goldstein, J. L. Adams, K.

Hambarsoomian, D. J. Klein, and M. N. Elliott, “Reporting CAHPS and HEDIS Data by Race/Ethnicity for

Medicare Beneficiaries,” Health Services Research Vol. 48, No. 2 Pt 1, 2013, pp. 417–434.

22

OMH, “Part C and D Performance Data Stratified by Race, Ethnicity, and Gender,” database, Centers for

Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2020. As of January 4, 2020: https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-

Information/OMH/research-and-data/statistics-and-data/stratified-reporting.html

7

Table 2.1. Database Search Strategy

Concept MeSH Search Terms

Health equity Health equity; healthcare disparities Equity; disparit*

Social risk Social determinants of health;

socioeconomic factors; safety-net

providers

Social determinants; social risk;

safety net; race; ethnicity

Performance measurement Value-based purchasing; incentive

reimbursement

Performance measure; quality

measure; value-based purchasing;

pay for performance; quality

reporting; public reporting; CAHPS;

HEDIS

NOTE: The search syntax was as follows:

1. "health equity".sh,kf.

2. "healthcare disparities".sh.

3. "equity".ti,ab.

4. "disparit*".ti,ab.

5. "social determinants of health".sh.

6. "social determinants".ti,ab.

7. "social risk".ti,ab.

8. "socioeconomic factors".sh.

9. "safety-net providers".sh.

10. "safety net".ti,ab.

11. "race".ti,ab.

12. "ethnicity".ti,ab.

13. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12

14. "value-based purchasing".ti,ab,sh.

15. "reimbursement, incentive".sh.

16. "performance measure".ti,ab,kf.

17. "quality measure".ti,ab,kf.

18. "pay for performance".ti,ab.

19. "quality reporting".ti,ab.

20. "public reporting".ti,ab.

21. "CAHPS".ti,ab.

22. "HEDIS".ti,ab.

23. 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22

24. 13 and 23

25. limit 24 to English language

26. limit 25 to yr="2010-Current"

8

List 2.1. Seminal Reports Mined as Part of Our Purposive Snowball Approach

Anderson, A. C., E. O’Rourke, M. H. Chin, N. A. Ponce, S. M. Bernheim, and H. Burstin, “Promoting Health

Equity and Eliminating Disparities Through Performance Measurement and Payment,” Health Affairs, Vol. 37,

No. 3, 2018, pp. 371–377.

ASPE Report to Congress: Social Risk Factors and Performance Under Medicare’s Value-Based Purchasing

Programs (Study A), 2016.

ASPE Report to Congress: Social Risk Factors and Performance Under Medicare’s Value-Based Purchasing

Programs (Study B), 2020.

Damberg, C. L., M. N. Elliott, and B. A. Ewing, “Pay-for-Performance Schemes That Use Patient and Provider

Categories Would Reduce Payment Disparities,” Health Affairs, Vol. 34, No. 1, 2015, pp. 134–142.

Hughes, D., J. Levi, J. Heinrich, and H. Mittmann, Developing a Framework to Measure the Health Equity

Impact of Accountable Communities for Health, Washington, D.C.: Funders Forum on Accountable Health,

2020.

National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, Accounting for Social Risk Factors in Medicare

Payment: Identifying Social Risk Factors, Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press and HHS, 2016.

9

List 2.2. Articles and Reports That Met Eligibility Criteria but Were Not Included in the Final

Results

Articles and reports describing measures of structures, systems, and processes within a health care

organization that promote delivery of equitable care

• Hughes, D., J. Levi, J. Heinrich, and H. Mittmann, Developing a Framework to Measure the Health Equity

Impact of Accountable Communities for Health, Washington, D.C.: Funders Forum on Accountable Health,

2020.

• Cultural Competency 2010 Measures and Implementation Strategies, Washington, D.C.: NQF, 2011.

• Healthcare Disparities and Cultural Competency Consensus Standards Technical Report, Washington

D.C.: NQF, 2012.

• Ng, J. H., M. A. Tirodkar, J. B. French, H. E. Spalt, L. M. Ward, S. C. Haffer, N. Hewitt, D. Rey, and S. H.

Scholle, “Health Quality Measures Addressing Disparities in Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate

Services: What are Current Gaps?” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, Vol. 28, No. 3,

2017, pp. 1012–1029.

• Weech-Maldonado, R., A. Carle, B. Weidmer, M. Hurtado, Q. Ngo-Metzger, and R. D. Hays, “The

Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) Cultural Competence (CC) Item

Set,” Medical Care, Vol. 50, No. 9, Suppl 2, 2012, pp. S22–S31.

• Weech-Maldonado, R., J. Dreachslin, J. Brown, R. Pradhan, K. L. Rubin, C. Schiller, and R. D. Hays,

“Cultural Competency Assessment Tool for Hospitals (CCATH): Evaluating Hospitals' Adherence to the

CLAS Standards,” Health Care Management Review, Vol. 37, No. 1, 2012, pp. 54–66.

• Weech-Maldonado, R., M. N. Elliott, J. L. Adams, A. M. Haviland, D. J. Klein, K. Hambarsoomian, C.

Edwards, J. W. Dembosky, and S. Gaillot, “Do Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Quality and Patient Experience

Within Medicare Plans Generalize Across Measures and Racial/Ethnic Groups?” Health Services

Research, Vol. 50, No. 6, 2015, pp. 1829–1849.

• Weech-Maldonado, R., M. Elliott, et al. “Can Hospital Cultural Competency Reduce Disparities in Patient

Experiences with Care?” Medical Care, Vol. 50, 2012, pp. S48–S55.

Reports of national disparities in health care

• The National Impact Assessment of CMS Quality Measures Reports, Baltimore, Md.: CMS, February

2020.

• Martino, S. C., M. N. Elliott, J. W. Dembosky, K. Hambarsoomian, Q. Burkhart, D. J. Klein, J. Gildner, and

A. M. Haviland, Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Disparities in Health Care in Medicare Advantage, Baltimore,

Md: CMS OMH, 2020.

• Martino, S. C., M. N. Elliott, J. W. Dembosky, K. Hambarsoomian, Q. Burkhart, D. J. Klein, J. Gildner, and

A. M. Haviland, Rural-Urban Disparities in Health Care in Medicare, Baltimore, Md.: CMS OMH, 2019.

10

Figure 2.1. Literature Review Flow Diagram

Records identified in

MEDLINE/CINAHL

(n = 675)

Records identified through other

sources

(n = 128)

Records after duplicates removed

(n = 783)

Records screened

(n = 783)

Records excluded

(n = 647)

Full-text articles/reports

assessed for eligibility

(n = 136)

Full-text articles/reports

excluded

(n = 125)

Articles/reports included in

synthesis

(n = 11)

Records identified in

MEDLINE/CINAHL

(n = 675)

Records identified through other

sources

(n = 128)

Records after duplicates removed

(n = 783)

Records screened

(n = 783)

Records excluded

(n = 647)

Full-text articles/reports

assessed for eligibility

(n = 136)

Full-text articles/reports

excluded

(n = 125)

Articles/reports included in

synthesis

(n = 11)

Identification

Screening

Eligibility

Included

11

Table 2.2. Summary of the Health Equity Measurement Approaches Identified by the Literature Review

Measurement Approach Setting/Population Social Risk Factor(s)

1. Measurement Framework for Evaluating How Well an Organization Meets

National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services

(HHS OMH)

Health care organizations Race/ethnicity; limited English

proficiency; low literacy

2. NQF Disparities-Sensitive Measure Assessment Cross-cutting Race/ethnicity

3. AHRQ National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report Overall U.S. population Age; sex, race/ethnicity

4. CMS OMH Mapping Medicare Disparities Tool Medicare FFS Race/ethnicity; dual eligibility; sex; age

5. CMS OMH Reporting of CAHPS and HEDIS Data by Race/Ethnicity for

Medicare Beneficiaries

MA and prescription drug plans,

Medicare FFS

Race/ethnicity

6. Minnesota Healthcare Disparities Report Minnesota health plan enrollees Race, ethnicity, preferred language,

country of origin

7. CMS Assessment of Hospital Disparities for Dual-Eligible Patients Hospitals Dual eligibility

8. CMS OMH Health Equity Summary Score Medicare Advantage plans Race/ethnicity; dual eligibility

9. Zimmerman Health-Related Quality of Life Approach to Assessing Health

Equity

General adult U.S. population Race/ethnicity; sex; income

10. Zimmerman and Anderson Approach to Evaluating Trends over Time in

Health Equity

General adult U.S. population Race/ethnicity; sex; income

NOTE: CAHPS = Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems; CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; DHHS = U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services; FFS = fee-for-service; HEDIS = Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set; MA = Medicare Advantage; NQF = National

Quality Forum; OMH = Office of Minority Health.

12

3. Detailed Information on Identified Approaches

In this chapter, we describe in detail the health equity measurement approaches that were

identified by the literature described in the preceding chapter. A summary of these

measurement approaches appears in the following chapter, which also introduces a

categorization scheme by which the measurement approaches are ordered here and

elsewhere.

Measurement Framework for Evaluating How Well an Organization Meets

National CLAS Standards (HHS OMH)

Overview. This report—which was commissioned by HHS OMH— describes a framework

for measuring whether structures, systems, or processes hypothesized to promote health

equity are in place within a health care organization or system.

23

Background. The National CLAS Standards are a set of 15 standards intended to advance

health equity and help eliminate health care disparities by providing a blueprint for health

care organizations to implement culturally and linguistically appropriate services. The

essential goal of the standards is framed in the Principal Standard: Provide effective,

equitable, understandable, and respectful quality care and services that are responsive to

diverse cultural health beliefs and practices, preferred languages, health literacy, and other

communication needs. The other 14 standards address domains of governance, leadership,

and workforce; communication and language assistance; and engagement, continuous

improvement, and accountability.

Design and methods. The goal of this approach is to identify a set of well-constructed and

validated health equity process and impact measures that could be applied to four settings

of care—ambulatory care, hospitals, behavioral health, and public health—to evaluate how

well a health care organization meets the National CLAS Standards. Specific criteria were

used by the authors of this framework to identify salient measures to consider, including

whether the measure (a) assesses cultural competency; (b) captures language needs or

preferences and/or is linked to other CLAS-related issues; (c) documents disparities; (d) is

validated and/or psychometrically tested; (e) is widely used or suitable for use by a range

of health care organizations; (f) has been previously endorsed in commissioned projects or

reports for evaluating disparities; and (g) cuts across conditions and/or settings. Measures

were categorized as cross-cutting (i.e., applicable across multiple settings) or setting-

specific. Based on the criteria, the authors identified six cross-cutting measures (see Table

3.1), six ambulatory-specific measures, nine hospital-specific measures, five behavioral

health–specific measures, and six public health–specific measures. Appendix A shows

measures that fit the latter four categories.

23

L. M. Davis, L. T. Martin, A. Fremont, R. Weech-Maldonado, M. V. Williams, and A. Kim, Development of a

Long-Term Evaluation Framework for the National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate

Services (CLAS) in Health and Health Care, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, EP-68215, 2018.

13

Table 3.1. Cross-Cutting Measures to Evaluate How Well an Organization Meets National CLAS

Standards

Measure Description

Clinician/group’s cultural

competence based on the CAHPS

Cultural Competence Item Set

Domains from CAHPS Cultural Competence Item Set: patient-provider

communication; complementary and alternative medicine; experiences of

discrimination due to race/ethnicity, insurance, or language; experiences leading

to trust or distrust, including level of trust, caring, and confidence in the

truthfulness of a provider; and linguistic competency (access to language

services)

Clinician/group’s health literacy

practices based on the CAHPS

Item Set for Addressing Health

Literacy

Domains from CAHPS Item Set for Addressing Health Literacy: communication

with provider, disease self-management, communication about medicines,

communication about test results, and communication about forms.

Patients receiving language

services supported by qualified

language services providers

Percentage of patients with limited English proficiency receiving both initial

assessment and discharge instructions supported by assessed and trained

interpreters or from bilingual providers and bilingual workers/employees assessed

for language proficiency

Screening for preferred spoken

language for health care

Percentage of patient visits and admissions in which the preferred spoken

language for health care is screened and recorded.

Cultural Competency

Implementation Measure

Survey of degree to which health care organizations are providing culturally

competent care and addressing the needs of diverse populations, as well as their

adherence to 12 of the 45 NQF-endorsed cultural competency practices.

Communication Climate

Assessment Toolkit

360-degree organizational assessment using coordinated patient, staff, and

leadership surveys, as well as an organizational workbook that collects important

information on the organization’s policies and practices.

14

NQF Disparities-Sensitive Measure Assessment

Overview. This report presents a protocol to systematically screen and identify NQF-

endorsed measures as disparities-sensitive.

24

The set of measures identified by this

approach was developed for use across health care settings.

Background. To establish a platform for addressing health care disparities and cultural

competency in measurement, NQF sought to identify measures from within its existing

portfolio of endorsed measures that might be disparities-sensitive (see below). In

particular, NQF sought to identify measures sensitive to health care disparities and cultural

competency for racial and ethnic minority populations. They established criteria to

evaluate measures for how sensitive they were to disparities, assigned points to each

measure based on these criteria, and set point thresholds and other rules to identify

disparities-sensitive measures.

Design and methods. To evaluate existing measures for disparities sensitivity, two tiers of

criteria were established that placed emphasis on prevalence and impact of the condition,

quality gap, and impact of the quality process.

25

The first-tier criteria—applied to

condition-specific measures and measures of health care access and quality—included the