The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy,

Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015

Rebecca Tunstall

Working Paper 18

January 2015

2

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Kathleen Kelly, Stuart Lowe, Ruth Lupton, Bert Provan, Rachael Takens-

Milne, David Utting, Sharon Witherspoon and staff at the Centre for Housing Policy at the University of

York for their comments on drafts of this paper.

The paper draws on Office for National Statistics (ONS) statistics which are subject to Crown copyright

and are reproduced under the Open Government Licence v.3.0.

3

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

Contents

Summary .................................................................................................................................................... 5

1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 8

2. The Coalition’s housing policy goals.................................................................................................. 13

The Coalition Agreement ................................................................................................................... 13

The Localism Act 2011 ...................................................................................................................... 15

Laying the Foundations 2011 ............................................................................................................ 16

The Welfare Reform Act 2012 ........................................................................................................... 17

Other policies .................................................................................................................................... 19

Summary: The Coalition’s orientation towards housing .................................................................... 20

3. Spending on housing ......................................................................................................................... 24

How national spending changes affected UK nations, regions and local government ...................... 30

UK government spending on housing benefit, 2009/10-2013/14....................................................... 32

Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 34

4. Outputs .............................................................................................................................................. 35

Impacts on “Increasing the number of available homes” ................................................................... 36

Impact on “helping people to buy a home” ........................................................................................ 38

Results on “Improving the rented sector”........................................................................................... 39

Impact on “Simplifying the welfare system and making sure work pays” .......................................... 40

Impact on “Providing housing support for older and vulnerable people” ........................................... 41

Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 42

5. Policy outcomes ................................................................................................................................ 43

Housing affordability .......................................................................................................................... 43

Homelessness ................................................................................................................................... 45

The effect of policy on different social groups ................................................................................... 46

6. Conclusions ....................................................................................................................................... 48

References ............................................................................................................................................... 51

List of Boxes

Box 1: Housing and housing-linked policy goals in the Coalition Agreement ........................................... 14

Box 2: Housing and housing-linked policy goals in the Localism Act 2011 .............................................. 15

Box 3: Additional policy in the Laying the Foundations housing strategy document, 2011 ...................... 16

Box 4: Housing-linked policy in the Welfare Reform Act 2012 ................................................................. 18

Box 5: Summary of Coalition housing and housing-linked policy goals and the departments responsible

for achieving them .................................................................................................................................... 22

Box 6: Key DCLG business plan indicators for housing policy in England ............................................... 22

4

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

List of Figures

Figure 1: UK ‘housing and community amenities’ expenditure (including housebuilding) grew rapidly

under Labour, 1997/98-2009/10 in real terms (2009/10 prices), £bn ....................................................... 10

Figure 2: UK government housing and community amenities expenditure dropped by 35% under the

Coalition 2009/10-2013/14 in real terms (at 2009/2010 prices), £bn…………………………………..25

Figure 3: DCLG’s capital budgets for England dropped by 54% 2009/10-2014/15 in real terms (2009/10

prices), £bn ............................................................................................................................................... 27

Figure 4:UK government ‘housing and community amenities’ expenditure dropped by 35% 2009/10-

2013/14 in real terms (at 2009/2010 prices), £bn ..................................................................................... 28

Figure 5:UK ‘housing development’ expenditure (mainly for building social housing) dropped by 44%

2009/10-2012/13 in real terms (at 2009/10 prices), £bn ........................................................................... 29

Figure 6: UK ‘Housing and community amenities’ expenditure cuts were concentrated on England

(expenditure in the nations of the UK, 2007/08-2011/12, real terms, (2009/10 prices), £ per head) ........ 30

Figure 7: ‘Housing and community amenities’ expenditure per person fell particular sharply in the North

East and London (expenditure in the regions of England the UK, 2007/08-2011/12, real terms (2009/10

prices), £ per head) .................................................................................................................................. 31

Figure 8: UK housing benefit spending grew by 9% in real terms 2009/10-2012/13 (at 2009/10 prices),

£bn ............................................................................................................................................................ 32

Figure 9: UK housing spending continued to switch from housing development to housing benefit

(spending on sub-categories within ‘housing and community amenities’ and ‘housing: social protection’),

UK, 2008/09-2012/13, in real terms (2009/10 prices), £bn ....................................................................... 33

Figure 10: UK house building completions fell by 8% 2009/10-2013/14, although house building starts

increased (see below), suggesting a new trend ....................................................................................... 36

Figure 11: Affordability for home buyers did not improve in England 2010-2013 (ratios between median

house prices and median income and between lower quartile prices and lower quartile income) ........... 43

Figure 12: The number of households accepted as unintentionally homeless and in priority need in

England grew by 26% 2010-2014 ............................................................................................................ 46

Figure 13: The number of households accepted as homeless and now living in temporary

accommodation in England grew by 14% 2010-2014 .............................................................................. 46

Table

Table 1: Progress on DCLG business plan indicators for housing policy in England under the

Coalition……………………………...…………………………………………………………………………….35

5

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

Summary

Coalition housing policy changes have all further reduced the extent of UK central government involvement

in housing, the ‘wobbly pillar’ of the welfare state, and some have reduced the extent of contributions by

the public sector in general. However they have certainly affected the ability of the Coalition both to achieve

its immediate housing policy goals and to address structural issues, including insufficient supply and

systemic risks.

The Coaltion has set some important precedents including devolution in the planning system, setting

housing association rents above traditional ‘social rent’ levels, undertaking social housing development

without public subsidy, ending the assumption of security of tenure for council tenants, and setting housing

benefit at sub-cost levels, leaving tenants with ‘shortfalls’.

Athough there have been no major changes in homelessness policy, Coalition changes have weakened

the two main housing elements of the UK’s welfare state ‘safety net’, social housing and housing benefit,

transferring risk to individual households and to some extent to social landlords.

In spend terms, helping tenants in existing homes and their landlords via housing benefit, rather than

supporting new house building, already dominated total government expenditure on housing when the

Coalition took power (unless tax concessions to owners and landlords are taken into account). The

Coalition continued the trend of shifting government expenditure from new development to housing benefit.

Despite attempts to reduce housing benefit eligibility, and some savings from individual reforms, total

housing benefit expenditure increased by 9% 2009/10-2012/13.

In contrast:

All other forms of government spending on housing in the UK were cut by 35% in real terms

2009/10-2012/13

Expenditure on new house building was cut by 44% in real terms 2009/10-2012/13

DCLG’s revenue budgets (which support spending by English local authorities on housing, such

as services to homeless people, housing-linked support for vulnerable people and regulation of

the private rented sector, as well as other services) for England dropped by at least 41%

2009/10-2014/15 in real terms

DCLG capital budgets for England were cut by 54% 2009/10-2014/15 in real terms, reducing the

options for local authorities to devote capital resources to housing provision.

Thus housing has contributed more than ‘its share’ to deficit reduction which the Coalition’s first housing

minister required. These particularly sharp cuts were another very marked break with the Labour era. In

fact budget cuts for DCLG and for housing and local government in England 2010-2014 under the

Coalition were equivalent in scale to the budgetary transitions immediately after 1945, when the UK

government was withdrawing at speed from its war footing (Taylor-Gooby 2012).

The one major exception to the spending cuts on housing was the boost given to housing purchase,

development and lending from 2012 through Help to Buy, although this still left spending below historic

levels.

Cuts were concentrated in England, and felt much less in the nations of the UK, most of which already

had higher funding per head than England.

6

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

Despite the cuts, looking at the seven specific housing indicators for England set out in the DCLG business

plan (detailed in Appendix 2) the Coalition government was able to show progress on five: The first four

relate to house building starts and completions:

In relation to completions although the number of home completions fell, the number of new home

starts increased very slightly 2009/10-2012/13, by 3% across the UK and by 8% in England. There

was then a big jump which meant an overall 40% increase in England 2009/10-2013/14. This

appeared to be linked to the “Help to Buy” programme providing subsidy to first time buyers

(described more below) and to improving economic conditions generally.

the number of affordable housing starts also jumped, although not as much (23%). This was the

opposite effect to what might be expected from reduced government support, although it was a

very short term effect and in an improving economic climate.

Turning to the other indicators:

The average SAP energy efficiency rating of homes improved slightly, through the effects of

government schemes but also the activities of owners.

There was a slight increase in the already high proportion of planning applications receiving assent,

although the numbers of applications actually made were low compared to historic patterns.

Finally, the number of households in temporary accommodation grew by 14%, despite the DCLG

business plan intention to see a reduction. The number of households accepted by local authorities

as homeless and in priority need also grew (26%), as did the number of people counted as street

homeless (37%).

Nevertheless, considering the Coalition's broader housing policy goals, it has had no significant and

unambiguous successes.

The Coalition’s average new home production is still below that of the previous government, and

does not constitute a major advance on structural undersupply. Questions remain: can this recent

increase in development be significantly accelerated, because absolute numbers of additional

homes are still well below acknowledged needs, and can this increasebe sustained over several

years, to meet the backlog of need.

In addition, it is not evident that this increase is being achieved in a cost-effective way and one that

does not increase systemic risks. Help to Buy is intended to be temporary, and, arguably, runs the

risk of exacerbating long-term structural issues like affordability problems and high and potentially

volatile prices. In addition, the nation’s social landlords have finite supplies of capital and borrowing

ability to use to build homes without government support, and beyond that would put themselves

and their tenants at risk. These measures indicate that the new house building achieved was not

sufficient alone to prevent the most serious implications of weak supply and unaffordability

problems getting worse. In terms of the affordability of house purchase, price to income ratios for

home buyers have not improved, although Help to Buy and the actions of lenders have eased

access for some by reducing deposit requirements.

More generally, the proportion of households spending more than a third of their income on

housing, a standard measure of affordability, has been stable at about 14%, or one in seven. The

7

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

amount of ‘affordable’ housing available is steady, but Coalition precedents mean it is becoming

less ‘affordable’. Home ownership has continued to decline in relation to other tenures.

With reduced regulation and reduced funding, the Coalition did not have the policy tools to

improve the quality of the rental sector. Social housing reforms have created precedents which

markedly reduced the housing element of the welfare state safety net.

The overall impact of welfare reform, rising social housing rents and increased use of the private

rented sector on work incentives and employment rates is ambiguous. However, housing benefit

reforms have also reduced the housing element of the welfare safety net.

Older people have been protected from welfare reform. Otherwise it appears that older and

more vulnerable people are less rather than more like to receive housing related support they

need under the Coalition, due to budget cuts, although relevant data sources have been

cancelled.

The Coalition undertook to ensure that richer people would make a greater contribution to

deficit reduction than poorer people (HM Treasury. 2010). However, most of the effects of

Coalition housing policy appear to be at best neutral between income groups, and at worst

markedly regressive. Some groups have gained including people with flexible rate mortgages,

those in areas where housing prices have recovered and grown, some of those taking up Help

to Buy and larger developers.

By 2014, towards the end of the Coalition government term, the structural problems problems in

the housing system, acknowledged by the Coalition, remained unresolved.

Given continued plans for fiscal constraint by all major parties, and housing’s continuing vulnerable

position, it would be difficult for future governments to fully reverse Coalition budget reductions and

consequent policy changes.

8

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

1. Introduction

This is one of a series of papers examining aspects of the social policy record of the Conservative/Liberal

Democrat Coalition in England from 2010-15, with a particular focus on poverty, inequality and the

distribution of social and economic outcomes. The papers follow a similar but smaller set covering

Labour’s record from 1997-2010, published in 2013. The current series follows the same format as the

earlier papers. Starting with a brief assessment of the situation the Coalition inherited from Labour, the

papers move to a description of the Coalition’s aims (as discerned from manifestos, the Coalition

Agreement and subsequent policy statements) and the policies enacted. The papers then describe trends

in spending on the area under consideration, and an account of what was bought with the money expended

(inputs and outputs). Finally, they turn to outcomes, and a discussion of the relationship between policies,

spending and outcomes, so far as this can be determined.

Housing differs in some ways from the other policy areas examined by the series. Housing has been

described as “the wobbly pillar” under the welfare state (Torgerson 1987), because of the partial extent to

which it has ever been taken over as a responsibility of government and of social policy. The private and

voluntary sectors play a substantial role in all aspects of housing policy, including finance raising, decision-

making and even in regulation (through self-regulation). Further, housing devolution and privatisation have

played a substantial role in moves to roll back the role of the state (eg Harloe 1995, Kemeny 2001,

Hodkinson and Robbins 2013). Thus a full examination of housing policy may incorporate reviewing the

policies affecting local government, private and voluntary sector organisations (Lupton et al. 2013a).

Housing is also ‘wobbly’ in the sense that as a capital-intensive and non-statutory area of expenditure, it

is at particular risk of cuts of central and local budgets in times of fiscal withdrawal.

In addition, housing is unusual because of the way in which it was implicated as amongst the causes of

the Global Financial Crisis, through securitised mortgages in the USA. Peoples’ behaviour toward their

housing assets played a role in the shape of the on-going downturn in the UK. From 2007, prices fell and

the number of sales transactions reduced: “The depressed housing market is, of course, one of the

contributors to the downturn in household consumption” (Pawson and Wilcox 2013 p47). From 2009, home

owners with mortgages were ‘saving’ by paying down their mortgages, rather than withdrawing equity from

their homes to fund consumption, as they had been doing in the early 2000s, which amounted to “a huge

retraction of economic stimulus” (Pawson and Wilcox 2013 p47).

The boundaries of ‘housing policy’ are also particularly blurred: policy on new housing development

extended into planning policy more broadly; policy on housing finance and encouragement of home

ownership extends into financial services and macroeconomic policy; policy on housing affordability and

low cost rental housing extends via housing benefit into welfare policy more broadly; housing is subject to

taxation and forms part of fiscal policy. This paper covers policy towards private housing for those on a

wide range of incomes, as well as social housing.

Housing policy is devolved to the Scottish government, Welsh Government and Northern Irish Government,

and macroeconomic policy and benefits policy are retained at UK level (Wong et al. 2011). The Welsh and

Northern Irish governments have weaker legislative powers, although devolution continued to evolve. In

fact one of the early policy goals stated in the Coalition Agreement was to resolve disagreement between

the UK and Wales over a Welsh request for additional housing powers (Twinch 2010). In England, policies

and financial decisions which affect housing outcomes and are made by the UK government, while in

9

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland they are made by both the UK and national governments. This paper

focusses on English housing policy, inputs, outputs and outcomes. Key points of similarity and difference

between England and the other UK nations are highlighted, but a full four country comparison is beyond

its scope.

The Coalition’s inheritance from the 1997-2010 Labour government

Progress and structural problems

An assessment of English housing policy 1975-2000, commissioned by Communities and Local

Government, noted successes in narrow terms, alongside trade-offs, unintended consequences; and

strategic weaknesses. Housing quality, choice and wealth had increased markedly over the period, but

demand ran ahead of supply, there were affordability problems, tenure and spatial polarisation, and

fragmentation of governance. Individual and systemic risk meant that the market was unstable, with

potential knock-on effects for the economy (Stephens et al. 2005). Under Labour, the Government itself

continued to agree, “The housing market has structural problems” (DETR 2000 p7).

Labour housing policy until the Global Financial Crisis

For the 1997-2010 Labour governments, as for the Thatcher and Major governments before them, the

position of housing within social policy was ambiguous at best. On the one hand, social housing was a

key area for efforts to ’roll back’ the state (through the Right to Buy and the switch from council housing to

housing associations). On the other hand, there was active government support for growth of home

ownership, and latterly for the private rented sector as well (Hodkinson and Robbins 2013). There were

tensions between the state’s desire for retrenchment and its ambition to govern the housing system,

particularly over restructuring social housing and encouraging new development.

At the start of the series of Labour governments from 1997, Hills argued,

“‘Housing policy’ per se hardly exists any more: it survives within the welfare state mainly as an

adjunct of social security (through Housing Benefit) or as part of wider city regeneration policies”

(Hills 1998 p13).

However, housing policy enjoyed something of a revival under Labour, playing a moderately prominent

role in the government’s programmes and activities, with continuation of many earlier policies, some

attempt to address the acknowledged structural issues, an interest in social exclusion and neighbourhood

regeneration, and substantial spending.

From 1999, the Decent Homes programme set a new housing quality standard and funding aimed to

ensure all social housing reached the ‘decent’ standard by 2010. The programme had a budget of £50bn

over ten years (at year 2009/10 prices) which amounted to about £13,000 for every social rented home in

England. This paid for 1m new central heating systems, rewiring in 740,000 homes, 700,000 new kitchens

and 525,000 new bathrooms (House of Commons Communities and Local Government Committee 2010).

By 2008, 73% of social rented homes met the standard, behind target but ahead of private sector housing

at 64% (Tunstall 2011). There was also an ambitious and fairly successful programme of neighbourhood

renewal, which included improvements to social and private housing and residential environments (Lupton

et al. 2013b).

10

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

Despite this, problems remained linked to concentrations of poverty in some social housing estates,

echoing the wider polarisation in the social make-up of different tenures, and the fact that restrictions

remained on local government autonomy over housing expenditure as government finance was tightly

controlled from the centre (Hills 2007). By the early 2000s, insufficient new housing supply against

household projections had become a relatively high profile policy issue. The Sustainable Communities

Plan promised 2m new homes by 2016, or 150,000 per year (ODPM 2003). The government encouraged

new housing development through Regional Spatial Strategies with targets for new house building by

region and local authority, through a target for the reuse of previously developed (‘brownfield’) land, and

continuing capital subsidies for the development of social housing. Investigations into low supply and rising

prices identified the planning system as a major culprit (Barker 2004), alongside problems in the structure

of the development industry and wealth inequality. Low tax, lack of alternative investments and the

development of Buy to Let mortgages were pointed to by other commentators (Dorling 2014).

As in other policy areas, there was dramatic growth in government expenditure on ‘housing’ across the

UK, from the second Labour term starting in 2001. UN regulations define a ‘housing and community

amenities’ spending category, including housing development and repairs by local authorities and other

social landlords, community development and housing-linked infrastructure

1

. The majority of expenditure

on housing and community amenities is on housing development by local authorities and other social

landlords. UK government housing and community amenities spending in peaked in 2009/10 at £16.3bn

(Figure 1).

Figure 1: UK ‘housing and community amenities’ expenditure (including housebuilding) grew

rapidly under Labour, 1997/98-2009/10 in real terms (2009/10 prices), £bn

Source: PESA 2012 Table 4.3

As we will explore below, ‘housing and community amenities’ expenditure does not include the cost of

housing benefit. There are also other government contributions to housing through the more notional cost

of net tax advantages to owner occupiers (concessions on capital gains and inheritance and the fact they

1

Water supply, street lighting and research and development on housing and community amenities. The category

excludes broader regeneration funding.

£0

£2

£4

£6

£8

£10

£12

£14

£16

£18

11

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

are not taxed on ‘imputed rents’, the flow of benefits from housing). By the mid-1990s, both housing benefit

and tax concessions each significantly outweighed expenditure labelled as ‘housing and community

amenities’ (Hills 2007).

A series of incremental changes affected housing for disadvantaged people. Some Conservative

limitations to rights for homelessness people were partially reversed. A substantial effort to reduce rough

sleeping resulting in a reduction in official counts from 1,850 people in England in 1997/8 to 440 in

2009/10

2

, although official counts were disputed

3

. On the other hand, social housing landlords were given

new powers to address anti-social behaviour, including ‘introductory’ (temporary, initial) tenancies. The

growing cost of Housing Benefit was addressed through limitations on the ability of non-working tenants

in the private rented sector to claim 100% of their rent, with a cap set at a ‘Local Housing Allowance’

pegged to local median rents according to household size. Meanwhile, the average price of a home rose

from £75,000 in 1997 to £189,000 in 2007. Social housing waiting lists grew, and the number of homeless

households in temporary accommodation in England grew from about 50,000 in 1997 to almost double

that by 2006

4

.

Labour housing policy during the Global Financial Crisis

By the mid-2000s, given the unprecedented period of economic growth, unprecedented housing price

growth, and the identification of systematic risks, change in the housing market was not unpredicted or

unpredictable (Hall 2011). For example, in 2005 a housing association executive said,

“’The market is changing faster than ever before… it has changed in one way over the last three

to four years, but it could change in another way in the future’” (quoted in Tunstall and Coulter

2006 p62).

Housing was directly implicated in the ‘credit crunch’ and the recession which followed it, as Stephens et

al. had warned (2005), and was in turn directly affected by them. From 2007, the earliest signs of recession

began to show in the UK. There was a drop in new housing development and in house prices, both leading

indicators of economic problems. In themselves, these lead to reduced employment, consumption,

demand, and GDP.

From 2008, lenders began to be increasingly cautious, in particular demanding higher deposits. This added

to existing affordability problems due to big price increases over the 2000s. In 2009, the Bank of England

commenced a low interest rate policy, with bank base rates dropping from 4.7% to 0.6% in 2009 and then

0.5% in 2010 (Wilcox et al. 2014). This protected existing borrowers who benefited by £20bn (FSA 2010)

and maintained access for new buyers, but meant that any future rate rises posed potential risks. From

2008, the Labour government began to alter its housing policies in response to the credit crunch, banking

crisis and housing market downturn. Hall noted, “Treasury and Bank of England intervention and support

for the UK housing market were both substantial and unprecedented” (Hall 2011 p74). A Special Liquidity

Scheme and a Credit Guarantee Scheme lent lenders £312bn, to be repaid by 2014 (Hall 2011).

2

CLG (2010) Total of street counts in England; Previous published figures on the street count of people sleeping

rough in England, by local authority, 1998-2009 [online] Last accessed November 2014,

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/rough-sleeping-in-england-total-street-count-and-estimates-2010

3

Voluntary sector counts produced estimates ten times higher. [online] Last accessed December 2014

http://www.londonspovertyprofile.org.uk/indicators/topics/housing-and-homelessness/rough-sleeping-in-london/

4

DCLG Livetable 777 Statutory homelessness: households in temporary accommodation in London and England,

at the end of each quarter, 1998 to 2014 [online] Last accessed November 2014,

www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-homelessnesstistical

12

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

Government temporarily raised the threshold for stamp duty from £125,000 to £250,000 for first time

buyers and those in disadvantaged areas, and provided bridging funding to help development schemes

which had stalled due to uncertainty about sales.

13

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

2. The Coalition’s housing policy goals

Unlike in some other policy areas, the Coalition Agreement in May 2010 cannot be treated as the principal

source of Coalition housing policy goals. The most important Coalition housing goals have to be identified

from a range of sources

5

. They also have to be identified partly from evidence on the policies themselves,

as well as from resources devoted to them and their impact: as Lupton et al. warned, “statements of policy

goals are only statements” (Lupton et al. 2013a p4). Budget decisions have been among the main tools

for and constraints on Coalition housing policy.

The Coalition Agreement

The Coalition Agreement contained a number of specific pledges linked to housing policy (Box 1). It also

contained a substantial number of pledges on the planning system, which have implications for the

development of new housing. However, there were fewer than half as many references to housing and

homes as to health, and education and schools. In addition, some of the housing pledges were very minor

(eg ‘Home on the Farm’). This partly reflects the limited attention given to housing in both Conservative

and Liberal Democrat manifestos (Conservative Party 2010, Liberal Democrat Party 2010). In addition, a

majority of the housing items in the Agreement had not been in either Coalition party manifesto

(Conservative Party 2010, Liberal Democrat Party 2010).

A number of items in the Conservative manifesto did not appear in the Agreement but did appear in

subsequent policies, particularly a pledge to cancel the introduction of Home Information Packs (also in

the Liberal Democrat manifesto), and series of changes to the planning system.

The Conservative manifesto pledge to retain the raised threshold for stamp duty was modified in the

Agreement, and the pledge to give equity stakes to ‘good’ social tenants, and creating a ‘Right to Move’

did not appear in the agreement (or subsequent policy) (Conservative Party 2010). The pledge to ‘respect

the tenure and rents’ of social housing tenants, repeated by the Prime Minister in a speech as late as 2012

(Hodkinson and Robbins 2013), was only kept for existing tenants, given the introduction of fixed-term

tenancies and ‘Affordable Rents’ (Conservative Party 2010).

The two Liberal Democrat manifesto pledges that were most distinctive and ideologically distant to those

of the Conservatives, the pledge to investigate changing public sector borrowing requirement accounting

rules to allow local authorities to borrow more, and pledge to scale back the HomeBuy scheme, did not

make it into the Agreement (Liberal Democrat Party 2010). Rather than scaling back support to home

owners, the Coalition subsequently introduced the Help to Buy scheme which was much larger than

HomeBuy.

5

The sources used to identify the Coalition’s housing policy goals were the Coalition Agreement (HM Govt 2010),

The ‘Emergency’ (June 2010) budget and other budgets, the Comprehensive Spending Review, the Localism Act

2011, Welfare Reform Act 2012 and regulations and orders, Laying the Foundations: A housing strategy for

England, 2011, statements on www.gov.uk, ministerial speeches and departmental announcements including some

pre-2010 shadow speeches, and some pre- and post-2010 think tank papers.

14

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

Overall, the Coalition Agreement was a less useful guide to housing policy than to policy in other areas.

No mention was made in the Coalition Agreement of some policies which subsequently proved significant,

including changes to Housing Benefit rules, or the level of investment in social housing, and precedents

set.

Box 1: Housing and housing-linked policy goals in the Coalition Agreement

Helping people to buy homes

1. We will promote shared ownership schemes and help social tenants and others to

own or part-own their home.

2. We will review the effectiveness of the raising of the stamp duty threshold for first-

time buyers (amended from promise to sustain the raise in the Conservative

manifesto).

3. We will provide more protection against aggressive bailiffs and unreasonable

charging orders, ensure that courts have the power to insist that repossession is

always a last resort, and ban orders for sale on unsecured debts of less than £25,000

(mentioned in the Conservative manifesto; similar policy in the Liberal Democrat

manifesto).

Improving the rented sector (council housing)

4. We will… review the unfair Housing Revenue Account (a partial alternative to

exploring opportunities to enable local authorities to borrow more, mentioned in the

Liberal Democrat manifesto).

Planning (affecting new house building and supply)

5. We will rapidly abolish Regional Spatial Strategies and return decision-making

powers on housing and planning to local councils, including giving councils new

powers to stop ‘garden grabbing’.

6. We will create new trusts that will make it simpler for communities to provide homes

for local people (mentioned in the Conservative manifesto).

7. We will promote ‘Home on the Farm’ schemes that encourage farmers to convert

existing buildings into affordable housing.

8. We will provide incentives for local authorities to deliver sustainable development,

including for new homes and businesses.

9. We will explore a range of measures to bring empty homes into use (mentioned in

the Liberal Democrat manifesto).

Providing housing support for older and vulnerable people

10. We will help elderly people live at home for longer through solutions such as home

adaptations and community support programmes.

Other

11. We will require continuous improvements to the energy efficiency of new housing.

12. Through our ‘Green Deal’, we will encourage home energy efficiency improvements

paid for by savings from energy bills (mentioned in the Conservative manifesto;

similar ideas mentioned in the Liberal Democrat manifesto).

13. We will take forward the Sustainable Homes Legislative Competence Order.

14. We will end the ban on social tenants starting businesses in their own homes.

Source: HM Government 2010

15

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

The Localism Act 2011

The Localism Act was passed in March 2011. As part of its attempts to reduce bureaucracy, and devolve

decision-making, it introduced important changes for social housing and planning, with implications for

two of the main goals (Box 2).

Box 2: Housing and housing-linked policy goals in the Localism Act 2011

“Improving the rented sector” (mainly social housing)

Option for local authorities and registered providers to set 5-year ‘standard’ rather than indefinite or

lifetime ‘secure’ tenancies

Options for local authorities on access to and allocation of social housing

Option for local authorities to satisfy their duty towards homeless households with an offer of private

rented accommodation (and no offer of social rented housing)

“Increasing the number of available homes”

Abolition of Regional Spatial Strategies and regional and local authority house building targets

Introduction of a new National Planning Framework

Introduction of neighbourhood plans, powers to stop ‘garden grabbing’, other use ‘use class’ changes,

and the re-reissue of Planning Policy Guidance note 3 (planning advice to local authorities on

housing).

Source: Localism Act 2011

The Act contained what was described as “a radical programme of reform” for social housing (HM

Government 2011 p.ix), giving local authorities and ‘registered providers’

6

new options on the length of

tenancies, and local authorities new options on access to and allocation of social housing. Social housing

“must provide the support that people need, when they need it, but also be a springboard for social mobility”

(HM Government 2011 pix). The idea was to more closely target tenancies on the periods of greatest

need (particularly when on low incomes) and through this to discourage indefinite long term occupancy

of of social housing.

Social housing allocation by local authorities reformed, with the entitlement to a social home no longer

being less strictly determined by housing need, and at the same time greater priority being permitted for

economically active households, and other groups such as ex-service personnel. The automatic long term

security of tenure for new social housing tenants was abolished. Previously a household was given a

council home for life (with slightly weaker rights for housing association tenants). Under Labour there had

been what in hindsight appeared a relatively modest reform, allowing landlords to offer an initial temporary

‘probationary’ tenancy to new tenants for the first year, with conversion dependent on good behaviour.

The vast majority of landlords were using this power by 2010, although the vast majority of tenancies were

successfully converted into secure ones after the first year. Under the Coalition, landlords were now

allowed to offer fixed term tenancies of only five years as standard if they chose to do so, with extension

dependent not only on good behaviour but on evidence of continuing housing need, a very marked change.

A large minority of landlords began to experiment with the new power and in 2012/13 9% of new lettings

6

Other officially-recognised providers of social housing, mainly housing associations

16

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

were fixed term tenancies (Chartered Institute of Housing 2014). Hodkinson and Robbins described the

reforms as “reframing of social housing as a privilege for the deserving poor” (2013 p70).

The Act also allowed local authorities to ‘discharge’ (fulfil) their duty to homeless households by helping

to organise tenancies in the private rented sector, rather than by providing them with tenancies in social

housing. Again, this built on but markedly extended a Labour change. The previous Labour government

had allowed local authorities to discharge their duty in the private rented sector but only if the homeless

household agreed to it.

The Localism Act also introduced significant changes to the planning system. A number of them appeared

to make getting planning permission easier or more predictable, if at the expense of housing or

environmental quality, such as the general presumption in favour of development, and the re-reissue of

Planning Policy Guidance note 3 (planning advice to local authorities on housing). However, others had

unpredictable or potentially negative effects, such as the abolition of Regional Spatial Strategies and

regional and local authority house building targets, and neighbourhood planning. Wong et al referred to

the widespread independent assessment that,

“Spatial planning in England has gone through major change and uncertainty since the formation

of the coalition government” (Wong et al. 2011p45).

Laying the Foundations 2011

In 2011 the Government published a “comprehensive” housing strategy for England (Prisk 2012a). This

was described as a “perfect example” of the Coalition approach to policy more generally (HM Government

2011 pv). Its most important elements were expenditure on getting the housing market moving and helping

people to buy homes, and deregulation of development (Box 3).

Box 3: Additional policy in the Laying the Foundations housing strategy document, 2011

“Increasing the number of available homes”

Funding and permission for various schemes to bring empty homes into use

Allowing renegotiation of pre-2010 ‘section 106’ planning agreements between local authorities and

housing developers (through which developers contribute to infrastructure and affordable housing)

Community Infrastructure Levy charges to replace negotiated ‘Section 106’ money and in-kind

contributions from developers to compensate local authorities and communities for the costs of

development with a proportion made available to communities to spend; potential for business rate

retention in addition

‘Growing places’ fund to pay for infrastructure associated with new housing

‘Get Britain Building’ fund to lend to developers with stalled schemes

‘Build now, pay later’ schemes allowing developers temporary free access to public land

Bridging finance for households developing ‘custom homes’

“Helping people to buy a home”

Help to Buy

Extension of discounts available under the Right to Buy

Source: HM Government 2011

17

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

From 2011, policy towards home ownership appeared to shift from policies mainly aimed at managing the

effects of the recession to those with longer term goals on supply and restructuring (Hall 2011). 95%

mortgages, which had made up the majority of products available before 2008, had become rare and more

costly, and high prices after the growth of the 2000s meant that a 5% deposit was on average a potentially

prohibitive £10,000. The Coalition introduced a major new policy, Help to Buy, to bridge the gap between

what lenders were demanding and what aspirant buyers could afford. This built on previous policies but

was on a much larger scale (NAO 2014b). Help to Buy had two forms: firstly, government equity loans to

buyers of up to 20% and secondly, near-full government mortgage guarantees to lenders of up to 30%.

Both enabled 95% mortgages for all buyers of homes priced up to £600,000. The NewBuy scheme, the

only element linked to additional supply, enabled 95% mortgages for first time buyers to buy newly-built

homes priced up to £500,000. The equity loans involved a total of £3.5bn in loans and the mortgage

guarantee involved a total of £12bn in guarantees over the life of the schemes (Chandler and Disney 2014,

HM Treasury 2014 a, b). These large sums are not grants or simple government spending but in effect

forms of loans, which government expects will be paid back. However, they carry an opportunity cost and

risk: payback depends on the extent of default, changes in house prices, interest rates and inflation.

The Right to Buy, introduced by Margaret Thatcher in 1980, is probably the best known of all British

housing policies, and has been seen as an emblem of welfare state restructuring (Hodkinson et al. 2013).

Annual sales peaked at 167,000 in 1982/83; by 2010 they had fallen to 6,000 per year (Wilcox et al. 2014).

The most attractive homes were no longer available, discounts had not kept pace with prices, and the

recession had affected all types of sales. The Coalition wanted to ‘reinvigorate’ the policy, as a symbolic

act, and as a means to advance low cost home ownership (DCLG 2012a). In April 2012, the maximum

discount was extended to £75,000 in England and to £100,000 in London. This would cost £45m a year

at the rate of sales seen in 2010, or more if rates increased. Meanwhile, in Scotland the Scottish

Government went in the opposite direction, effectively ending the Right to Buy on the grounds that it

depleted the stock of affordable housing (Wilcox 2014).

The Welfare Reform Act 2012

Spending on housing benefit constitutes a major element of total government expenditure on housing

policy across the UK (Hills 2007), although it does not directly build, maintain or improve any actual housing

stock. Rather than being an investment in housing stock, it is paid to landlords for existing homes. It

subsidises households to meet the costs of renting accommodation in the social or private rented sectors,

where household income from work or benefits is too low to meet rent demands. Thus in effect it may

subsidise low pay. As set out above this expenditure had by the mid-1990s become greater than “housing

and community amenities” spending. Both the Labour governments and Coalition government sought to

reduce expenditure, as well as to avoid work disincentives.

The Coalition built directly on Labour changes affecting private renters. Labour had set a maximum

payment at the median local market rent, regardless of the actual rent charged – so that private renters

would either have to find accommodation at a cost below this level, or fund higher rents themselves. From

2011, the cap or ‘Local Housing Allowance’ (LHA) was set at the 30

th

percentile of local market rents (in

other words, so only rents for the cheapest third of homes would be fully funded). In addition, weekly LHA

was capped at £400, regardless of household size or actual rent asked and paid. From 2013, LHA caps

increased in line with a new, generally less generous measure of inflation (the consumer price index rather

18

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

than the retail price index) (Hodkinson and Robbins 2013) - meaning that the number of properties at rents

where housing benefit would cover all the cost was progressively reduced.

The Welfare Reform Act 2012 contained important additional changes to the benefit for social tenants,

each of which aimed to reduce the overall cost to the Treasury, and to create particular forms of ‘fairness’

between claimants and others, alongside other policy goals (Box 4).

Box 4: Housing-linked policy in the Welfare Reform Act 2012

“Simplifying the welfare system and making sure work pays”

Housing Benefit changes for social rented tenants including reduced benefit where there was a

“spare” bedroom (widely known as the ‘bedroom tax’)

As part of the Universal Credit provisions, ‘direct payments’ of housing benefit to social rented

tenants, who would then pay landlords (rather than payments straight to landlords)

Benefits Cap setting maximum benefit of £500/week for couples and £350 /week for single people,

including Housing Benefit, regardless of eligibility

Extension of Discretionary Housing Payment budgets for local authorities to mitigate impact of change

on a temporary and discretionary basis

Source: Welfare Reform Act 2012

The social rented sector size criterion (widely known as the ‘bedroom tax’) aimed to level eligibility for

housing space for social rented tenants claiming housing benefit down to that of private rented tenants.

However, this was levelling down rather than up. In addition, while the 559,000 households were affected

when the policy started, they made up just 4% of those ‘under occupying’ in total (Wilcox 2014). Unlike the

policy for private renters, it was introduced for all tenancies, not just new ones, and in a tenure which much

higher portions of tenants had made their lifelong home and of whom much higher proportions had

disabilities or other special needs. The policy also aimed to improve mobility, with the idea of ‘freeing up’

larger homes (DWP 2012). In effect the aims of savings for government and fairness or efficiency were in

conflict: either people did not move, leading to savings for the government, or other goals related to better

use of the stock were achieved. In practice, by far the biggest effect has been savings for the government,

although the policy contributed just 2% of all cuts by 2014/15 (Wilcox 2014) and did not prevent an overall

increase in housing benefit expenditure.

The main overarching policy intended to ‘simplify’ the welfare system was Universal Credit. This was

intended to provide a combined replacement for Housing Benefit, Job Seekers’ Allowance, Employment

Support Allowance and some tax credits. The single benefit would be easier to understand and would

mean that claimants were not subject to varied and multiple clawbacks as their incomes rose.

As part of this, overall change, Direct Payments of housing benefit were intended to make tenants take

responsibility for budgeting, and, potentially, to create a level playing field between social and private

landlords, who generally already had to get rent from tenants and manage the risk of arrears. Social

landlords were concerned about the potential for arrears and bad debts and increased cuts and risks of

collecting income from tenants, rather than from the Department of Work and Pensions.

Local authorities already had Discretionary Housing Payments (DHP) budgets to support residents facing

short-term problems meeting housing costs. In response to welfare reform, DHP budgets for local

authorities were increased to £60m in 2012/13, £180m in 2013/14 and £165m in 2014/15 (Wilson 2014).

Some local authorities did not spend all their budgets, and there were some questions about interpretation

of Department of Work and Pensions rules on eligibility (Wilcox 2014, Clarke et al. 2014a). The key point

19

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

is, however, that total DHP budgets, even including additional funds local authorities were permitted to

contribute, were only a small fraction of savings intended: “it was never the intention that DHPs would

mitigate the full impact of reductions in HB [Housing Benefit] entitlement” (Wilson 2014 p2). In addition,

future rounds of funding were uncertain. Local authority contributions were capped. The greater use of

DHPs was a marked development of the nations’ and English local authorities’ roles in the welfare system,

hitherto run almost entirely at UK level. The Scottish Government successfully requested permission to

make its own contributions to DHP budgets, sufficient to ensure that all those affected by the ‘bedroom

tax’ would be fully compensated, effectively ending the ‘tax’ in Scotland for 2014/15 (Wilson 2014).

Alongside the devolution of Council Tax benefit, the expansion of DHPs substantially increased local

variation and discretion in the welfare system.

Other policies

The ‘New Homes Bonus’ gave an incentive to local authorities to grant permission for development by

providing them with funds matching the council tax to be charged on new homes for the first six years of

their life. It was also to be paid when empty homes were brought back into use. It was hoped this would

support 140,000 extra homes 2011-2014. £1bn was set aside for payments over the period, although the

policy was intended to be revenue neutral overall and was taken from other local authority budgets (Wilson

2014b). The first payments were made in 2011.

The Coalition Agreement promised to review the temporary increase in the stamp duty threshold for first

time buyers and buyers in disadvantaged areas, a tax concession (HM Government 2010). There is no

evidence of a formal published review, but first ‘holiday’ ended in April 2012, as had been planned by New

Labour, and the second in April 2013.

As planned in the Coalition Agreement, Housing Revenue Account regulations were reviewed and local

authorities in England were required to refinance their housing accounts, in a once-off settlement involving

write-offs for some authorities before central government ceased involvement. This ended the historic role

of national government in the finance of council housing building and improvement and historic debt. It

represented a contribution to ‘localism’. It was of net benefit to most local authority housing departments

(Wilcox et al. 2014), but meant that henceforth, central government saw the finance of council housing

improvement as a matter for local authorities alone.

Policies also included the promotion of private renting, with one minister saying “we need a bigger and

better private rented sector” (Prisk 2013e). Since the 1980s, commentators on the UK housing system had

raised concerns about private rented housing supply (e.g. Rugg and Rhodes 2008). These were at least

partially superseded from 1988 when the sector began to increase as a proportion of the whole system.

By 2010 there were more households renting privately than in social housing. In addition, the purchase of

new build homes by those intending to rent them out (often termed “buy to rent”) had become widespread

and was causing concern in some markets from the mid-2000s. However, attempts to encourage

institutional investment and new build specifically for private renting persisted. Alongside the arguable ‘end’

of new social housing, (the move to minimal capital subsidy and higher rents), the 2011 budget announced

funding for pilots to encourage private landlords and investors to invest in new build for private renting at

full market rents (HM Government 2011). It also reduced stamp duty tax for large-scale purchase of homes.

The 2012 Finance Act altered the existing Real Estate Investment Trusts that provide tax breaks for

institutional investment in the housing market, particularly the private rented sector (Hodkinson and

Robbins 2013).

20

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

Summary: The Coalition’s orientation towards housing

There was considerable continuity between the broad goals of Labour and Coalition governments (eg

Crisp et al. 2009, Hodkinson and Robbins 2013, Archer and Cole 2014). However, there were clear

differences in the means to be used to achieve goals, and the new Government set a number of precedents.

The Coalition reduced many of the traditional sources of funding for housing (particularly in England) to a

dramatic extent. It ceased to provide capital subsidy to enable new development at rent levels traditional

for ‘social’ housing; removed the assumption that revenue payments of housing benefit to individuals

should cover all the rent for people living on out-of work benefits or similar incomes, at sub-cost levels –

and in doing this left thousands of tenants (including many working households) with ‘shortfalls’. It removed

the assumption of lifetime security of tenure for social housing tenants which had been introduced for

council tenants by Margaret Thatcher in 1980. The Coalition appeared to abandon the ambition to ‘govern’

the housing system, which had created tensions between goals for earlier governments. In turn, however,

this affected the ability of the Coalition to address structural issues, including insufficient supply and

systemic risks.

Conservative-linked think tanks, particularly Policy Exchange and the Centre for Social Justice, had carried

out substantial housing policy development during the period of opposition, with a particular focus on the

planning system (e.g. Centre for Social Justice Housing and Dependency Working Group 2008). The new

housing front bench also had considerable experience of housing policy. Thus the Coalition government

was able to commence rapidly on some quite substantial housing-linked projects, particularly in changing

the planning system, to reduce the role of government.

In opposition, the Conservative party had supported the argument that there were structural problems in

the housing system (Conservative Party 2010). A housing ‘bubble’ had been part of the cause of the

financial crisis as manifested in the UK (Conservative Party 2010). Coalition and Conservative ministers

stated that the housing system was “dysfunctional”, and suffered from “persistent market failure” (e.g.

Cameron and Clegg in HM Government 2011, Prisk 2012a, 2013b). This was shown, they felt, not only in

the slowdown since 2007, in which the housing system was both part cause and victim, but in at least

fifteen years’ undersupply of new homes, which it was argued had resulted in growing social housing

waiting lists, rising private rents and problems for younger people getting into home ownership. The

Coalition argued that by 2011, systematic problems had combined with the effects of the credit crunch and

recession, so that:

“buyers can’t buy… lenders aren’t lending enough… builders are not building… investors are not

investing… affordable housing can do more… tenants are struggling” (HM Government 2011 p.vi;

see also Shapps 2011d, Boles 2013).

Independent commentators also agreed that the housing system faced structural problems which

predated the recession, and had been evident possibly since the 1970s (e.g. Barker 2004. Stephens et

al. 2005, Wong et al. 2011, Whitehead and Williams 2011, Hall 2011). However, in a pre-election

assessment of developing policy, Crisp et al said, “‘it is currently difficult to discern anything resembling a

coherent Conservative policy on housing” (Crisp et al. 2009 p61).

Under the Coalition, the lead department for England, the Department of Communities and Local

Government, aimed to “meet people’s housing aspirations”, but had other goals too: “supporting

21

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

sustainable growth”, and “devolving as far as possible”

7

. In addition, DCLG was subordinate to the

Treasury. This had been the pattern under preceding governments. Hall argued,

“The importance of the UK housing market cuts across the political spectrum… Nonetheless, the

new coalition… has not given any priority to the housing market over other spending areas…

priority is given to deficit reduction” (2011 p78).

For the Coalition, housing policy and particular systemic issues were more clearly either subordinate to or

a means to achieve economic policy goals for growth and deficit reduction: “We need to get the housing

market… moving again. This is central for our plans for economic growth” (HM Government 2011 pvii).

Housing development itself would create jobs and economic demand.

By improving access to home ownership, housing policy might contribute to social mobility, health and

wellbeing (HM Government 2011), and to some extent, economic policy could be used as a means to

achieve housing policy goals. For example, the first Coalition housing minister said, “The best thing we

can do for the all-important First Time Buyer is to get the economy back onto a sound footing” (Shapps

2010a npn). However, the first time buyer was ‘all important’ because of their role in indicating and

stimulating macroeconomic demand. However, housing policy goals were clearly subsidiary to, and

constrained by, economic policy goals. Shapps also said, “Housing must take its share of the burden. If

we don’t there is a real threat to the economic future of this country” (2010b npn).

The Coalition did not explicitly considered whether and how long term goals such as increased home

ownership and reduced fluctuations in house prices could be achieved, and whether and institutions such

as the mortgage market and housing development market should be reformed.

In addition, the Coalition government also intended changes in the way that policy would be developed

and implemented. From their very first official statement, in May 2010, it declared that it wanted to build

the ‘Big Society’, in which state responsibilities for governance of all policy areas would be reduced:

“We want to give citizens, communities and local government the power and information they

need to come together, solve the problems they face and build the Britain they want” (Cabinet

Office 2010 p1).

The idea of ‘Big Society’ overlaps with the Coalition’s promotion of ‘localism’, encouraging more local

decision-making and responsibility within the state and outside. In this context, Eric Pickles, Secretary of

State for Communities and Local Government, said, “housing is the most market-oriented of all my

Department’s responsibilities. Policy should go with the grain of the market” (Pickles 2011 npn). In

speeches in their first years in government, ministers repeatedly told commercial and voluntary sector

audiences that they were doing and would continue to do the main work, and government role was to

assist: “when I say ‘we’, I really mean you. You are the ones who will do all the hard work” (Shapps 2011c).

Government’s policy tools would be incentives rather than targets and sanctions, alongside further

devolution in decision making (Shapps 2010a npn, HM Government 2011). It is worth noting that incentives

have direct fiscal costs, whereas targets may not. The previous Labour government’s use of new housing

targets was described as unproductive or even counterproductive (e.g. HM Govt 2011). In planning, local

opposition to new homes was to be overcome through direct financial incentives to local authorities and

7

DCLG Business Plan 2012-2015, [online] Last accessed November 2014

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/7527/2154390.pdf

22

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

community groups. This approach also acknowledges the substantially reduced funding the Coalition

would put into housing compared with the previous government (see inputs, below).

In this context, the main policies introduced are set out in the boxes below. Box 5 indicates the broad

housing policy goals the Coalition government itself identified by 2014, amongst its 224 overall stated

policy aims, mainly to be devolved through the Department for Communities and Local Government (Box

5). These policies apply to England; in the nations devolved governments would make and deliver their

own.

Box 5: Summary of Coalition housing and housing-linked policy goals and the departments

responsible for achieving them

“Increasing the number of available homes (Department of Communities and Local Government

(DCLG)

Helping people to buy a home (DCLG, HM Treasury and Homes and Communities Agency)

Improving the rented sector (DCLG)

Providing housing support for older and vulnerable people (DCLG)

Simplifying the welfare system and making sure work pays (Department of Work and Pensions)

Achieving strong and sustainable economic growth” (Department of Business, Industry and Skills, HM

Treasury and UK Export Finance)

Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/policies [online] Last accessed November 2014

It should be noted that these goals are framed in broad terms. To achieve some of them requires no more

than only some maintenance of outputs, such as some new homes, rather than maintenance of the same

volume or rate of production, let alone acceleration.

The government has adopted a set of key indicators to monitor its performance in policy delivery. It calls

these ‘impact indicators’, although a minority of them are indicators of spending or quality. DCLG set itself

seven key indicators for housing elements of its business plan for England (Box 6).

Box 6: Key DCLG business plan indicators for housing policy in England

New home starts

New home completions

Affordable housing starts

Affordable housing completions

Households in temporary accommodation

Average energy efficiency of new homes

Percentage of major and minor planning applications granted permission

Source: DCLG 2012b

23

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

Reviewing these policies, we can see that some familiar and some new contradictions and limitations

made their way into Coalition housing policy. Policies included the promotion of home ownership, despite

an acknowledgment that the tenure had declined over the 2000s, and that high and rising prices were at

least implicated in the overall downturn. Hall noted, “reluctance among policymakers to state that… future

price corrections are either unavoidable or UK residential property is too expensive to buy” (2011 p75).

Policies also included the promotion of private renting, despite an acknowledgement that part of the growth

of the sector represented delayed or frustrated home ownership. It was acknowledged that the housing

system was not providing sufficient supply, but there were new policies which were likely to make

development more difficult, when compared to trends or other things being equal, if not in absolute terms.

Similarly, policy intended to simplifying the welfare system and make work pay included new complications,

some administrative transitional costs, disrupted savings and potential long-term costs. Here, housing

policy goals were losing out to competing interests in deregulation, ‘localism’, a fairer or more popular

approach to welfare, or electoral politics.

24

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

3. Spending on housing

As long ago as the mid-1990s, it was recognised that the benefits to homeowners of tax concessions on

property ownership significantly outweighed wider government social policy expenditure on housing and

community amenities (Hills 2007). Given a government deficit, housing is a potential area where additional

taxation might have been introduced. Overall, however, the Coalition decided that the majority of its attack

on the UK budget deficit would be made up of spending cuts rather than extra taxes (or in this case,

reducing tax concessions). In addition, there was very little change to the tax position of housing. Some of

the small number of changes introduced actually increased concessions. Thus the vast majority of the

government’s economic policies for housing took the form of spending cuts (Lupton et al 2015).

In June 2010, just weeks after writing the Coalition Agreement, the Coalition agreed a special Emergency

Budget, to start work on the deficit and on reshaping the role of government in the economy. The next

sections report data on resources expended and planned budgets from the Public Expenditure Statistics

(PESA) for the UK, where available, and for England

8

,

9

.

Department of Communities and Local Government budgets for England 2009/10-2014/15

Budgets available for housing policy in England, for both capital investment and day to day (revenue)

spending, fell sharply under the Coalition government, Revenue budgets fell by at least 41% and capital

budgets by 54% 2009/10-2014/15,although there was a modest increase in capital budgeting from 2013/14

to pay for new housing policies.

The next sections cover:

Overall Department for Communities and Local Government revenue expenditure for England,

broken down into ‘communities’ and ‘local government’ categories, both of which include spending

on housing and on other items (Figure 2);

Overall Department for Communities and Local Government capital expenditure for England,

including spending on housing and on other items (Figure 3);

8

PESA data does not fully separate out housing budgets or expenditure. Many reported figures do not contain all

UK government housing budgets or spending; many include non-housing items. They do not include the more

notional costs of net tax advantages to owner occupiers (concessions on capital gains and inheritance and the fact

they were not taxed on ‘imputed rents’, the flow of benefits from housing). Nonetheless, PESA data provide a good

guide to budgets and expenditure. Data are available for the eight years 2008/09-2015/16. These are ‘outturn’

(actual expenditure) for the first five years, including the first three years of the Coalition, and planned budgets for

the last three years of the period.

9

PESA data distinguish between planned budgets and ‘outturn expenditure’ (actual expenditure), which may be

different to planned budgets. Within data on budgets, there is a further distinction between Departmental

Expenditure Limits (DEL) which departments must keep to, and Departmental Annual Managed Expenditure

(AME), which can fluctuate according to programme rules, demand or events. Together DEL and AME make up

Total Managed Expenditure (TME), defined in National Accounts terms as public sector current expenditure plus

public sector gross investment (measured net of sales but gross of depreciation) (HMT 2013a p16). These DEL

and AME budgets contain part but not all of UK central government budgets for housing in England, including

money due to be passed on to local government and public corporations for spending. DEL and AME also include

moneywhich will not be spent on housing. Each contains both ‘resource’ (revenue) and capital elements. The main

budgets of interest are those due to be sent by the Department of Communities and Local Government (DCLG).

These are in turn divided between budgets for the two ‘communities’ and ‘local government’ functions of DCLG.

Both of these include some housing expenditure.

25

WP18 The Coalition’s Record on Housing: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015.

UK government spending on ‘Housing and Community Amenities’, comprising housing

development, community development and housing-linked infrastructure (Figure 4), and

breakdowns for the countries of the UK and English regions (Figures 6, 7);

UK housing development expenditure (a sub-set of the above), mainly for building social housing

(Figure 5).

UK housing benefit expenditure (Figure 8).

Figure 2 reports DCLG’s fixed annual budgets for revenue expenditure (officially termed ‘Resource

Departmental Expenditure Limits’). These cover both ‘local government’ sub-department, including funds

local authorities spend on housing

10

, and a small contribution to the ‘communities’ sub-department,

including some spending on housing-linked activities provided by central government programmes such

as projects for rough sleepers and neighbourhood regeneration

11

. ‘‘Local Government’ expenditure

predominates. The budget total shows a dramatic downward trend in DCLG budgets from a peak at £37bn

(in 2012/13 prices) in the last full Labour government year 2009/2010, with a marked drop from 2012/13

to £18bn in 2013/14, with further reductions planned to £12bn in 2015/16.

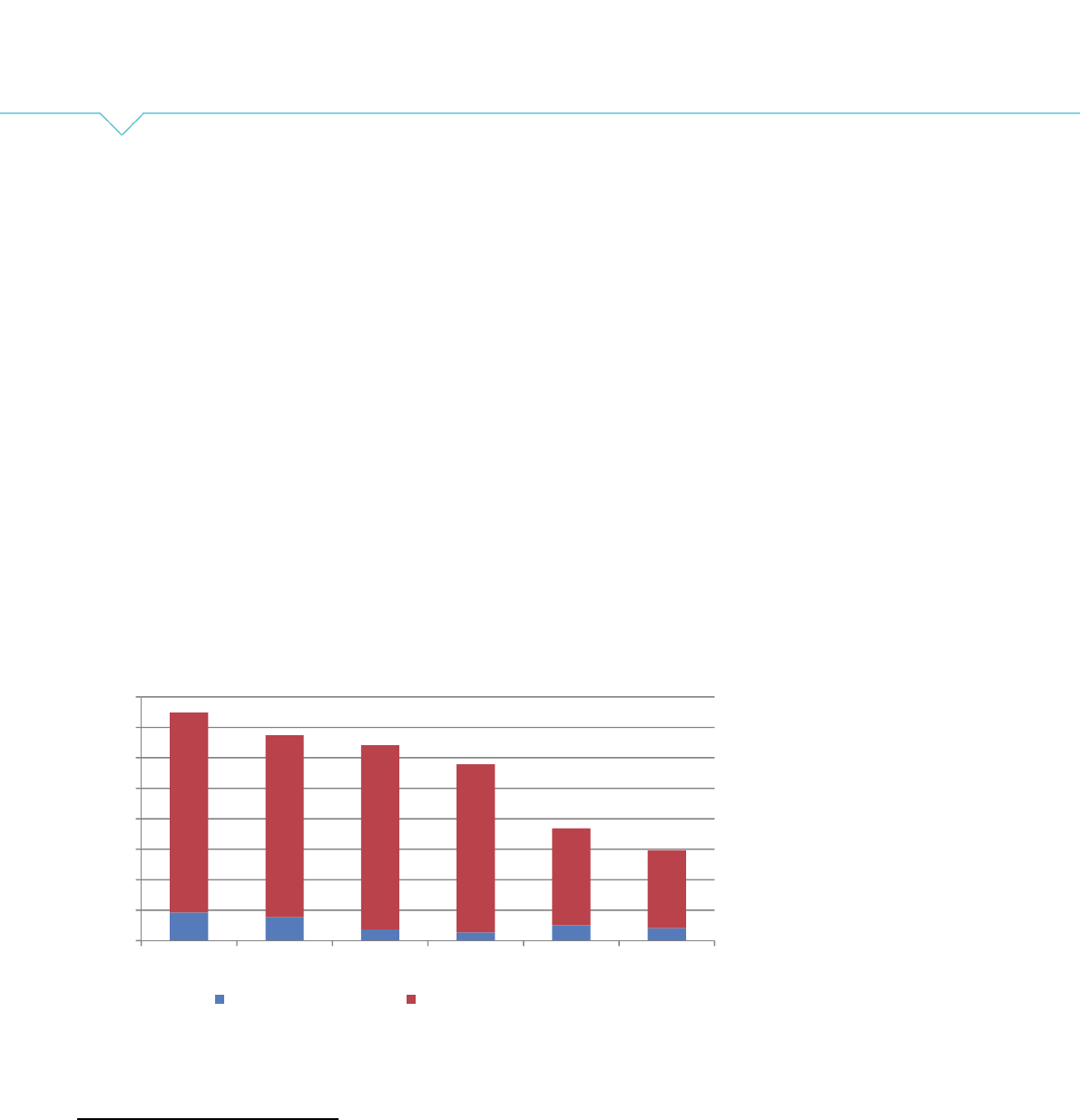

Figure 2: After rapid growth under Labour, UK government housing and community amenities

expenditure dropped by 35% under the Coalition 2009/10-2013/14 in real terms (at 2009/2010

prices), £bn

Source: PESA 2013 Table 1.4

10

This covers “Financial support to Local Authorities, including revenue support grant and business rates retention;

transitional relief; council tax freeze, localising council tax support, council tax benefit - new burdens, emergency

assistance, elected mayors; improvement, transformation and efficiency; intervention action and capacity building

in local authorities; local government reviews” (HM Government 2013 p156).

11

This covers “responsibility for the fire and rescue services… decentralising power to citizens and communities

and promoting the Big Society… promoting race, gender and faith equality; tackling extremism and promoting

sustainable, cohesive and integrated communities… tenant empowerment… rough sleepers and supporting people

to stay in their homes; building standards; support for homeowners; planning; Planning Inspectorate; encouraging

action at neighbourhood level… regeneration… zero carbon and climate change… Troubled Families… general

support for Local Authorities; supporting the implementation of the new rights included within the Localism Act

2011… research, monitoring, statistics… Non-Departmental Bodes including the Homes and Communities Agency”

(HM Government 2013 p154).

£0

£5

£10

£15

£20

£25

£30

£35

£40

2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15

CLG Communities CLG Local Government

26