Portland State University Portland State University

PDXScholar PDXScholar

Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses

Winter 3-14-2019

Physical and Emotional Sibling Violence and Child Physical and Emotional Sibling Violence and Child

Welfare: a Critical Realist Exploratory Study Welfare: a Critical Realist Exploratory Study

Katherine Elizabeth Winters

Portland State University

Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds

Part of the Social Work Commons

Let us know how access to this document bene=ts you.

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Winters, Katherine Elizabeth, "Physical and Emotional Sibling Violence and Child Welfare: a Critical Realist

Exploratory Study" (2019).

Dissertations and Theses.

Paper 4808.

https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6692

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations

and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more

accessible: [email protected].

Physical and Emotional Sibling Violence and Child Welfare:

A Critical Realist Exploratory Study

by

Katherine Elizabeth Winters

A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

in

Social Work and Social Research

Dissertation Committee:

Stephanie Wahab, Chair

Joan Shireman

Jana Meinhold

Eric Mankowski

Portland State University

2019

© 2019 Katherine Elizabeth Winters

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE i

Abstract

Sibling violence is a pervasive, yet poorly understood and substantially

underreported phenomenon. Currently recognized as the most common form of intra-

familial abuse, various estimates suggest that 30 percent or more of children in the

general population experience severe acts of violence inflicted by a sibling each year.

Given that many young people in the child welfare system experience the family

conditions associated with abusive sibling violence, recent publications have implored

child welfare to embrace the notion that it is a form of child maltreatment. Practitioners

and policymakers have yet to reach agreement on what constitutes physical or emotional

abuse between siblings, and the perspectives of young people with lived experience of

abuse are largely absent from research and scholarship.

I designed the study, grounded in Critical Realism, to increase understanding of

how sibling violence manifests in child welfare, contribute to theory development, and

identify actions to protect children from harm. Based on in-depth interviews with eight

foster care alumni, I offer a refined definition of sibling violence and four family

conditions associated with sibling violence in child welfare. The findings also supported

a systems-based theory reflecting four stable family member roles. My recommendations

seek to leverage the infrastructure of the child welfare system while taking into

consideration the limitations imposed by neoliberal social and economic policy.

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE ii

Dedication

This dissertation is dedicated to FosterClub for their partnership in this project,

the study participants who contributed so courageously to the interviews, and the foster

care alumni who served as advisers and whose guidance and recommendations

strengthened the study: Ashley Strange, Ke’Onda Johnson, TeAsia Hend, and Timothy

Dennis.

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE iii

Acknowledgements

Utmost gratitude to my adviser, Stephanie Wahab - your encouragement,

responsiveness, and pointed questions kept me steadily moving forward, with confidence.

Joan Shireman, this project benefitted tremendously from your sage wisdom of child

welfare and unwavering attention to its practice and policy implications. Janna Meinhold,

I count myself lucky for having such an enthusiastic thought partner. Eric Mankowski,

your gentle reminder to attend to my own heart was well-timed and did not fall on deaf

ears. Beverly Parsons, your mentorship in systems thinking has beautifully altered the

trajectory of my life. Amber Fletcher, your expertise in Critical Realism was my

guidepost. Emily Lott and Lindsay Merritt, walking this path alongside you has been an

honor and a privilege. And finally, to my family, thank you for giving me everything I

needed to learn so much.

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE iv

Table of Contents

Abstract ............................................................................................................................i

Dedication ...................................................................................................................... ii

Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... iii

List of Tables............................................................................................................... viii

List of Figures ................................................................................................................ ix

Chapter 1: Introduction .................................................................................................... 1

Social Problem Description and Definitions ......................................................... 1

Sibling Violence Theory ...................................................................................... 3

Sibling Violence Theory and Intervention in the Context of Child Welfare .......... 4

Critical Realism for Sibling Violence Research in Child Welfare ......................... 9

Study Purpose, Research Questions, and Significance to Social Science

Scholarship ........................................................................................................ 10

Chapter 2: Literature Review ......................................................................................... 13

Defining Abusive Sibling Violence .................................................................... 13

Abusive Sibling Violence in the Context of Child Welfare ................................. 15

Abusive Sibling Violence Trauma ...................................................................... 20

A Call to Action ................................................................................................. 21

Family Conditions Associated with Sibling Maltreatment .................................. 22

Sibling Violence Theory .................................................................................... 23

Social learning theory. ............................................................................ 23

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE v

Radical feminist theory. .......................................................................... 25

Conflict theory. ...................................................................................... 26

Coercive family process.......................................................................... 29

Social ecological model of violence. ....................................................... 31

Sibling Violence Interventions ........................................................................... 32

Micro- and meso-level interventions. ...................................................... 32

Macro-level influences and interventions. ............................................... 37

Holistic, coordinated violence prevention intervention. ........................... 39

Chapter 3: Methodology ................................................................................................ 42

Realist Ontology ................................................................................................ 44

Constructivist Epistemology .............................................................................. 47

Methodology and Methods ................................................................................. 48

Study Pilot ......................................................................................................... 49

Study participant recruitment and consent process. ................................. 54

Data collection........................................................................................ 55

Data analysis. ......................................................................................... 57

Establishing Trustworthiness .............................................................................. 61

Ethical Considerations ....................................................................................... 62

Researcher Positionality ..................................................................................... 64

Chapter 4: Results.......................................................................................................... 66

Sample Description ............................................................................................ 67

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE vi

Research Question 1. How do foster care alumni describe their experiences with

physical and emotional sibling violence? ............................................................ 70

A nascent definition of abusive sibling violence in child welfare ............ 70

Family conditions associated with sibling violence ................................. 77

Resonance of linear and non-linear theories ............................................ 87

Research Question 2. From the perspective of foster care alumni, how do adults

who care for or work with young people involved in the child welfare system

(e.g., foster parents, case workers, mental health providers, kinship caregivers,

etc.) respond to sibling violence? ....................................................................... 99

Inadequacy of adult responses to sibling violence in child welfare .......... 99

Survivors’ recommendations to address the problem ............................ 103

Results of CR Retroduction .............................................................................. 104

Child maltreatment in political-economic context. ................................ 106

Chapter 5: Discussion .................................................................................................. 111

Raise Awareness and Provide Basic Training for Adults Charged with Ensuring

Family Safety ................................................................................................... 113

Refine and Adopt a Definition of Abusive Sibling Violence in Child Welfare .. 114

Systematically Assess and Track Abusive Sibling Violence Among Child

Welfare-involved Families ............................................................................... 115

Revisit Child Welfare Co-Placement Policy ..................................................... 116

Invest in Programs to Ensure Safe, Strong Sibling Relationships for Child

Welfare-Involved Youth .................................................................................. 116

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE vii

Inform and Engage the Public to Catalyze Community-Based Solutions .......... 118

Organize for a More Just, Equitable Society ..................................................... 119

Chapter 6: Conclusions ................................................................................................ 121

Study Strengths ................................................................................................ 124

Youth Perspectives. .............................................................................. 124

Critical Realism. ................................................................................... 126

Systems Thinking. ................................................................................ 126

Implications for Future Research ...................................................................... 127

Implications for Social Work ........................................................................... 128

Study Limitations ............................................................................................. 129

All female sample ................................................................................. 129

Individual perspectives. ........................................................................ 130

Investigator limitations ......................................................................... 130

References ................................................................................................................... 132

Appendices .................................................................................................................. 151

Appendix A: Recruitment Flyer ....................................................................... 151

Appendix B: Participant Informed Consent Document ..................................... 153

Appendix C: Data Collection Instruments: Interview Protocol and Background

Form ................................................................................................................ 158

Appendix D: Final Coding Scheme .................................................................. 165

Appendix E: Family Map Example .................................................................. 172

Appendix F: Human Subjects Application to IRB ............................................ 181

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE viii

List of Tables

Table 1. Characteristics of Sibling Rivalry and Sibling Violence .................................. 14

Table 2. NCANDS Child Maltreatment Perpetrator Categories and Percentages

in 2016 ......................................................................................................................... 16

Table 3. Sibling Study Adviser Conference Call Summary ........................................... 52

Table 4. Study Process Summary .................................................................................. 53

Table 5. Study Participants’ Reports of Physical and Emotional Sibling Violence ........ 68

Table 6. Family Conditions Associated with Sibling Violence ...................................... 78

Table 7. Final Set of Family Conditions Associated with Sibling

Violence in Child Welfare ............................................................................................ 80

Table 8. Family Conditions Associated with Sibling Violence Overall and by

Placement Type ............................................................................................................ 81

Table 9. Theory Code Descriptions ............................................................................... 88

Table 10. Final Set of Primary and Secondary Family Conditions for Sibling

Violence in Child Welfare with Associated Linear Theories ......................................... 92

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE ix

List of Figures

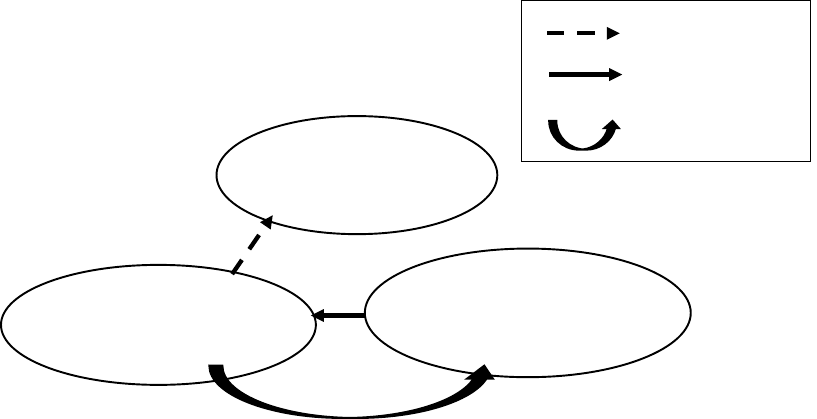

Figure 1. Integrated theoretical model of sibling physical and psychological abuse

(Hoffman and Edwards, 2004, p. 191). ........................................................................ 27

Figure 2. Ecological model for understanding violence (adapted from the World

Health Organization, 2002, p. 12). ............................................................................... 32

Figure 3. Ecological model for understanding violence (adapted from the World

Health Organization, 2002, p. 12). ............................................................................... 38

Figure 4. Coordinated violence prevention model: Hypothetical common and

specific elements (Hamby and Grych, 2013, p. 85). ..................................................... 40

Figure 5. CR domains of reality presented as an iceberg. ............................................. 45

Figure 6. Instigator/retaliator escalating abusive sibling violence dynamic with

reinforcing feedback loops. .......................................................................................... 74

Figure 7. Two biological siblings and their father. ....................................................... 95

Figure 8. Kinship care setting with two biological siblings and their foster sister. ........ 97

Figure 9. Biological family with four siblings.............................................................. 98

Figure 10. Retroduction results summarized in terms of the three domains of

reality. ......................................................................................................................... 110

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 1

Chapter 1: Introduction

Social Problem Description and Definitions

Sibling violence is a pervasive, yet poorly understood and substantially

underreported phenomenon. Currently recognized as the most common form of intra-

familial abuse (Button & Gealt, 2010), various estimates suggest that 30 percent or more

of children in the general population experience severe acts of violence inflicted by a

sibling each year (Caffaro, 2014; Finkelhor, Tuner, & Ormrod, 2006; Straus, Gelles, &

Steinmetz, 2006; Tucker, Finkelhor, Shattuck, & Turner, 2013). Common discourse

continues to minimize the problem (e.g., sibling rivalry, rough housing), and the

phenomenon is often treated as an accepted rite-of-passage. Yet differences in size and

physique between siblings, the developmental immaturity of children, and everyday close

contact within the household are likely to increase the frequency, intensity, and duration

of violent sibling interactions (Finkelhor et al., 2006). These findings are cause for

concern given robust evidence of numerous harmful effects of sibling violence across the

lifespan (Button & Gealt, 2010; Caffaro, 2011; Caffaro, 2014; Feinberg, Solmeyer, &

McHale, 2012; Finkelhor et al., 2006; Graham-Bermann, Cutler, Litzenberger, &

Schwartz, 1994; Kramer & Bank, 2005; Straus et al., 2006; Tucker et al., 2013). In the

absence of a caring adult who intervenes, chronic sibling violence may cause “toxic

stress,” which has been linked to physical and mental illness later in life (Shonkoff,

Boyce, & McEwen, 2009; Finkelhor et al., 2006).

Sibling violence theorists, practitioners, and researchers have attempted to define

what constitutes abusive physical and emotional violence between siblings. Wiehe

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 2

(1997), one of the first and more widely cited authors on the topic of sibling violence,

aligned the phenomenon with parent-to-child maltreatment by using the word “abuse”

when defining violent interactions between siblings. Caffaro (2014), a clinical

psychologist and family therapist, effectively differentiated healthy sibling conflict (i.e.,

rivalry) and abusive sibling violence in terms of aims, frequency, power, change over

time, and the role of caregivers. According to the author, abusive sibling violence is

marked by stable victim and offender roles. Caffaro’s emphasis on repetition is notable,

given that even low frequency peer violence (i.e., occurring less than four times per year)

has been significantly associated with trauma symptoms in young children (Finkelhor et

al., 2006). Meyers (2017) built upon the work of Caffaro and others in a qualitative study

with adult survivors. She argued that a comprehensive definition of abusive physical and

emotional violence between siblings should include the victim/survivor’s lived

experience/perception of what took place.

Despite commendable progress made over the course of more than three decades

of sibling violence research and scholarship, a clearly-articulated and broadly accepted

definition of “sibling abuse” is yet to be developed. In a review of more than 100 journal

articles, books, chapters, and dissertations published between 1977 and 2008, Perkins

(2014) found 16 different labels used to discuss emotional and physical violence between

siblings: sibling abuse, sibling aggression, sibling agonistic behavior, sibling antagonism,

sibling assault, sibling conflict, sibling fighting, sibling hostility, sibling maltreatment,

sibling negativity, sibling psychological abuse, sibling psychological maltreatment,

sibling quarreling, sibling relational aggression, sibling rivalry, and sibling violence (pgs.

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 3

34-35). Definitional variation is problematic, limiting interpretation of individual sibling

violence studies and the capacity of the field to draw comparisons among them.

Sibling Violence Theory

Theorizing about sibling violence is similarly nascent, traversing levels of the

social ecology from the interpersonal to the global. Social learning theory positions

sibling violence as a learned behavior which is fortified through reinforcement (Bandura,

Ross, & Ross, 1963; Hoffman & Edwards, 2004). Radical feminist theory argues that the

patriarchal organization of society and the related, pervasive acceptance of the use of

power and control to achieve desired aims underlie the phenomenon (Button & Gealt,

2010; Graham-Berman et al., 1994; Hoffman & Edwards, 2004; Hoffman, Kiecolt, &

Edwards, 2005; Wiehe, 1997). With roots in Marxism, conflict theory assumes that

humans are innately self-interested, and when located within a context of scarcity, will

utilize any means available to obtain desired resources. Sibling violence is theorized to be

a response to a child’s perception that necessary resources (e.g., basic needs, parental

attention) are scarce or inadequate (Hoffman et al., 2005; Smith & Hamon, 2012). While

these theories identify potential causal mechanisms underlying sibling violence, they rely

on reductionist linear models and differentiations between violence and abuse are

unclear.

Moving beyond linear, mechanistic models, a small subset of the literature

discusses systems-based conceptions of sibling violence. Family systems theory

(Milevsky, 2011), coercion theory (Granic & Patterson, 2006; Patterson, 1982; Smith,

Dishion, Shaw, Wilson, Winter, & Patterson, 2014), and an ecological model

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 4

(Bronfenbrenner, 1979) employ key systems concepts including holism, nesting, and

non-linearity to examine interpersonal violence as a complex and dynamic process that

spans local to global levels of a structurally violent society (Gil, 1996). In a

comprehensive review of theories of sibling relationships across the lifespan, Whiteman,

McHale & Soli (2011) summarize the current state of sibling violence theorizing,

acknowledging that:

…the processes that affect sibling relationship dynamics operate at a variety of

levels, ranging from intrapsychic processes, such as attachment and social

comparison, to relational dynamics, such as social learning and more distal forces

beyond the family, such as sociocultural influences. (p. 135)

While a small number of systems-oriented scholars have explored these ideas,

substantial additional effort is needed to understand the extent to which these conceptions

approximate reality.

Sibling Violence Theory and Intervention in the Context of Child Welfare

The current definition of child maltreatment, per the most recent iteration of the

Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) states:

…the term ‘child abuse and neglect’ means, at a minimum, any recent act or

failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker, which results in death, serious

physical or emotional harm… or an act or failure to act which presents an

imminent risk of serious harm” (Administration for Children and Families,

Division of Health and Human Services, 2016, p. 7).

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 5

Though intentionally vague, the CAPTA definition of child maltreatment does not fit

well with analysis of abusive sibling violence in that it assumes the perpetrator is a

parent. However, the latter part of the definition, focused on “imminent risk of serious

harm” can be employed given strong evidence that sibling-perpetrated physical and

emotional violence produce negative outcomes across the lifespan (Button & Gealt, 2010;

Caffaro, 2011; Caffaro, 2014; Feinberg et al., 2012; Finkelhor et al., 2006; Graham-

Bermann et al., 1994; Kramer & Bank, 2005; Straus et al., 2006; Tucker et al., 2013).

Data on physical and emotional violence between siblings are not systematically

collected in any of the three federally-maintained (i.e., national) child welfare data

systems: National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS), Adoption and

Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS), and National Incidence Studies

of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS) (Shireman, 2015). Moreover, many states exclude

sibling violence from definitions of child abuse (Caffaro, 2011), leaving direct service

practitioners ill-prepared to identify the problem among the children they serve

(Kominkiewicz, 2004). Increased emphasis on sibling co-placement in child welfare is

likely to further reduce attention to harmful sibling dynamics. This is notable given well-

intentioned and often beneficial federal policy mandating co-placement for siblings in

foster care.

1

In a review of the peer-reviewed empirical social work and psychology

literature published from 1988 through 2003, 17 studies addressing siblings in foster care

1

The Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008 (P.L. 110–351) requires that

reasonable efforts be made to place siblings in the same foster home and with kin whenever possible, and

over half of state child welfare systems prioritize sibling co-placement as a means of maintaining sibling

bonds (Gustavsson & MacEachron, 2010). For an in-depth discussion of legal protections accorded to

siblings in foster care, see Shlonsky, Bellamy, Elkins, & Ashare, 2005.

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 6

or adoption collectively demonstrated that sibling co-placement can support placement

stability and reduce symptomology among child welfare-involved youth (Hegar, 2005). A

subsequent meta-analysis similarly concluded that “most children benefit significantly

from living with their siblings” (Washington, 2007, p. 431). Juxtaposed with reports

indicating that significant numbers of siblings were not co-placed (Staff & Fein, 1992;

Washington, 2007; Wulczyn & Zimmerman, 2005), these findings powered a shift in

federal and state legislation toward strong emphasis on co-placement and, when placed

separately, the importance of ensuring regular visitation between siblings removed from

biological caregivers, both in the United States and abroad (Hegar, 2005; Kothari et al.,

2014).

The Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008 was

the first federal law to address the importance of sibling co-placement, requiring states to

make reasonable effort to maintain sibling connections when in foster care. Over half of

the states in the U.S. had established sibling placement or visitation policies prior to

passage of the Act, whereas others developed state-based policies specific to siblings in

foster care subsequent to its passage (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2013). Yet

neither the Act, nor its accompanying Program Instruction for Title IV-E agencies

include the word “abuse” and the Act does not address cases where co-placement is not

appropriate. Moreover, no standard protocol is available for caseworkers to use in making

decisions about co-placement when sibling abuse is present. This “best practice” (Cohn,

2008) guides a nationalized approach to care in which siblings who should not be co-

placed, or who should be co-placed only with strong supports, may be overlooked. In an

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 7

effort to bring much needed nuance to co-placement policy, Linares, Li, Shrout, Brody, &

Pettit (2007) argued that separation of siblings during foster care placement may be

beneficial, particularly for children with elevated levels of behavior and conduct

problems.

The lack of attention to sibling violence in child welfare is concerning given that

rates are likely high among maltreated children. Family conditions among children

exposed to sibling violence include many which are common in child welfare: parental

physical or emotional unavailability, lack of supervision, differential treatment of

children in the same family such as scapegoating, inappropriate caretaking expectations

placed on older sibling(s), parental acceptance of sibling violence as a normal part of

family life, lack of parent intervention during acts of sibling violence, parental modeling

of physically or emotionally abusive behavior, drug or alcohol abuse in the home, chronic

mental or physical illness of parent(s), work or financial strain, and parental denial of the

problem (Caffaro & Con-Caffaro; 1998; Wiehe, 1997). Moreover, studies have

demonstrated that sibling violence often co-occurs with other types of family violence

(i.e., adult-perpetrated child maltreatment, interpersonal violence between adult

caregivers) (Henning, Leitenberg, Coffey, Bennet, & Jankowski, 1997; Spaccarelli,

Sandler, & Roosa, 1994; Wallace, 1999; Wiehe, 1997). A small number of studies

support the notion that maltreated children are prone to sibling/peer violence (Linares et

al., 2007; Linares et al., 2015; Shields & Cincchetti, 1998, 2001). Linares et al. (2015)

found that 82 percent of foster parents reported past-year physical aggression acts

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 8

between siblings in their care; 14 percent of foster children had been “beat-up” by a

sibling while in their care (p. 211).

While the causal mechanisms underlying sibling violence are tentative, various

interventions have been devised to train both parents and children to more productively

and peacefully navigate sibling disputes. As early as 1967, clinicians were testing

approaches to reduce sibling aggression and increase cooperative play among general

samples (Kramer, 2004). More recent interventions have recommended various

combinations of individual, sibling, family, and group therapy and training sessions on

topics such as mediation, to reduce sibling violence (Caffaro & Conn-Caffaro,

2005; Caspi, 2008; Feinberg, Sakuma, Hostetler & McHale, 2013; Kennedy & Kramer,

2008; Kiselica & Morrill-Richards, 2007; Reid & Donovan, 1990; Thomas & Roberts,

2009; Siddiqui & Ross, 2004; Smith & Ross, 2007). Two studies have tested

interventions devised specifically for child welfare-involved siblings (Kothari et al.,

2017; Linares et al., 2015). Both interventions employ skill-building to support siblings

to cultivate relational and self-regulatory skills to enhance relationship quality. While

initial testing generated statistically significant results, the study conducted by Linares et

al. (2015) was subject to a small sample size and Kothari et al. (2017) did not include a

measure of sibling violence. More work is needed to develop and test interventions to

ameliorate violence between siblings within the context of child welfare and beyond.

Theory and intervention development for child-welfare involved siblings is

promising, given a recent call for social workers and mental health practitioners to attend

to physical and emotional sibling violence in their work with children and families and

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 9

social work’s “Grand Challenge” to stop family violence

2

(Kulkami, Barth, & Messing

2016; Meyers, 2014; Perkins & O’Connor, 2015; Perkins & Stoll, 2016; Shadik, Perkins,

& Kovacs, 2013). Yet without holistic understanding of the causal mechanisms

underlying sibling violence, interventions for child welfare-involved siblings are likely to

exclude potentially efficacious components or strategies. Moreover, the perspectives of

young people with lived experience with sibling violence are absent from theory and

research on the phenomenon in the context of child welfare. This lack of youth-informed

research and practice is misaligned with a body of research which has demonstrated that

young people have much to offer when it comes to social problems that affect them.

When asked to describe their experiences, share their perspectives, and provide

recommendations, young people can meaningfully contribute to efforts to parse complex

interpersonal processes, develop accurate definitions and measures, capitalize on sources

of resilience in intervention designs, and inform direct practice and policy-making

(Horwath, Kalyva, & Spyru, 2012; Hyde & Kammerer, 2009; Riebschleger, Day, &

Damashek, 2015; Strolin-Goltzman, Kollar, & Trinkle, 2010).

Critical Realism for Sibling Violence Research in Child Welfare

Critical Realism (CR) emerged in the 1970s and 1980s as an alternative paradigm

to positivism and constructivism. CR opens space to investigate ontological questions

about causation by employing constructivist epistemologies and methods by separating

2

Led by the American Academy of Social Work & Social Welfare (AAASWSW), the Grand Challenges

for Social Work is an initiative to champion social progress through social science, collaboration, and

shared projects. For more information about the Grand Challenges visit http://aaswsw.org/grand-

challenges-initiative/about/. For information about the challenge to stop family violence, see Kulkarni,

Barth, and Messing’s (2016) policy recommendations.

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 10

reality into three domains: the empirical, the actual, and the causal. According to this CR

stratification, the empirical domain (where social science research takes place) consists of

a subset of all events produced by an underlying causal mechanism. CR research

embraces both intensive (i.e., in-depth interpretive data) and extensive (i.e., data on

widespread trends, typically gathered with quantitative data) methods to identify

empirically observable patterns of human behavior which are then subjected to theory-

laden researcher-driven thought exercises to clarify causal processes (Lennox & Jurdi-

Hage, 2017; Sayer, 2010). CR is a well-suited philosophy to guide the current project

because its goal is to inform emancipatory action to dismantle system structures that

cause human suffering. This project, grounded in the CR paradigm, aims to identify

causal mechanisms underlying abusive sibling violence as it is described by foster care

alumni. The long-term objective is to inform direct practice, intervention development,

and child welfare policies that effectively reduce its prevalence. A more detailed

discussion of CR as it relates to the methodology and methods for this project is included

in Chapter 3.

Study Purpose, Research Questions, and Significance to Social Science Scholarship

This dissertation was designed to begin to fill gaps in theory, direct practice, and

policy by asking foster care alumni to share their experiences with sibling violence and

offer recommendations to address the problem. The study examined abusive sibling

violence, employing a working definition based on the work of Caffaro (2011) and

Meyers (2017): (1) a repeated, escalating pattern of physically and/or emotionally violent

interactions; (2) with stable victim/offender roles (i.e., unidirectional, (Caspi, 2012)); (3)

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 11

in which the offender is motivated by a need for power and control, and; (4) the victim

experiences a chronic sense of terror and powerlessness. Specifically, the study

investigated the extent to which such a definition was represented in the descriptions of

physical and emotional violence provided by foster care alumni.

3

The study was designed to generate information to clarify (i.e., better define) what

constitutes abusive sibling violence and to assess the fit and utility of family conditions

and theories of sibling violence discussed in the extant literature by incorporating the

perspectives of foster care alumni who have experienced it in the context of child

welfare. The research questions guiding the study included:

1) How do foster care alumni describe their experiences with physical and emotional

sibling violence?

a) To what extent do their descriptions fit with Caffaro (2014) and Meyers’

(2015) definitions of abusive sibling violence?

b) To what extent are family conditions and theories of sibling violence

discussed in the extant literature represented in their descriptions?

c) What additional/refined causal mechanisms do their descriptions suggest?

3

The inquiry will intentionally exclude sexual abuse between siblings. While physical, emotional, and

sexual abuse are likely to co-occur (Caffaro & Conn-Caffaro, 1998; Wiehe, 1997), the latter is not subject

to the definitional problems that physical and emotional abuse are. Sibling incest is a criminal behavior

prohibited by law in every U.S. state (Myers, 1998 as cited in Perkins, 2014). The current study will focus

on physical and emotional abuse since these types of sibling abuse are definitionally ambiguous and largely

neglected in the child welfare literature.

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 12

2) From the perspective of foster care alumni, how do adults who care for or work with

young people involved in the child welfare system (e.g., foster parents, case workers,

mental health providers, kinship caregivers, etc.) respond to sibling violence?

a) To what extent are adult responses perceived as helpful?

b) What do young people recommend to address sibling violence?

The goals of the study for Social Science scholarship, research, and practice were

multifold:

1. increase understanding of physical and emotional sibling violence in the context

of child welfare;

2. contribute to sibling violence theory development; and,

3. identify innovative ways to protect children from sibling violence and/or help

foster children manage sibling violence.

The chapters that follow provide a comprehensive review of the sibling violence

literature, both within and beyond the context of child welfare, describe the methods for

the study including the ontology, epistemology and methodology guiding the project, the

results of the study, and conclude with a discussion of the findings with emphasis on

practical recommendations to address sibling violence in child welfare and beyond.

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 13

Chapter 2: Literature Review

Defining Abusive Sibling Violence

Wiehe (1997), one of the first and more widely cited authors on the topic of

sibling violence, aligned the phenomenon with adult-perpetrated child maltreatment by

using the word “abuse” when defining violent interactions between siblings. According to

the author, physical abuse includes “willful acts resulting in physical injury such as

slapping, hitting, biting, kicking, or more violent behavior that may include the use of an

instrument, such as a stick, bat, gun, or knife” (pp. 14-18). Emotional abuse was defined

as “verbal comments aimed at ridiculing, insulting, threatening, or belittling. Emotional

abuse is also inclusive of the destruction of personal property, such as a sibling who

deliberately destroys a prized possession or pet of another sibling” (Wiehe, 1997, pp. 33-

34). In addition to providing a variety of tangible examples of acts which constitute

physical and emotional abuse, both definitions highlight the intent of one sibling to harm

another. Wiehe’s definition of physical violence also specifies that injury must result

from an act of violence to qualify as abusive.

According to Caffaro (2011), sibling violence is defined as “a range of behaviors

including pushing, hitting, kicking, beating, and using weapons to inflict physical harm,”

whereas psychological maltreatment includes “exposing a sibling to violence by peers or

other siblings; comments aimed at ridiculing, insulting, threatening, terrorizing, and

belittling a sibling; rejecting, degrading, and exploiting a sibling, and; destroying a

sibling’s personal property” (pgs. 8-10). The author differentiated healthy sibling conflict

and abusive sibling violence in terms of aims, frequency, power, change over time, and

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 14

the role of caregivers (Table 1). Most notably, abusive sibling violence is marked by

stable victim and offender roles. A shortcoming of Caffaro’s list of characteristics is that

it largely neglects to describe the markers of psychological maltreatment between

siblings.

Table 1

Characteristics of Sibling Rivalry and Sibling Violence (Caffaro, 2011, p. 91)

Sibling Rivalry

• Conflict between siblings in which the reward is possession of something that

the other also wants

• Conflict between siblings that strengthens their relationship

• Fierce but balanced comparisons between siblings with regard to achievement,

attractiveness, and social relations with peers

Sibling Violence

• A repeated pattern of physical aggression directed toward a sibling with the

intent to inflict harm and motivated by an internal emotional need for power

and control

• Physical aggression directed toward a sibling that aims to leave the other feeling

humiliated, defeated, and/or unsafe

• An escalating pattern of sibling aggression and retaliation that parents seem

unwilling or unable to stop

• Role rigidity resulting in the solidification of victim and offender sibling roles

More recently, Meyers (2017) conducted a qualitative study employing

phenomenological and grounded theory methods to gather survivor accounts to develop a

working definition of sibling abuse. Based on in-depth interviews with 19 survivors aged

25 to 65, analysis identified the unpredictable nature of the abusive incidents as an

essential marker of sibling abuse. Survivors recounted violent interactions which

occurred consistently over the course of years. Despite the long-term and frequent nature

of the abuse, the perception that they could not anticipate or avoid the assaults resulted in

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 15

a chronic sense of terror coupled with a perpetual state of powerlessness to self-protect.

Meyers’ findings also confirmed intent, duration, and a power differential between

siblings as key attributes of sibling abuse. A notable insight which can be garnered from

the inquiry is the idea that a comprehensive definition of abusive sibling violence should

include the victim/survivor’s lived experience/perception of what took place. The current

project assessed the extent to which there was resonance between the definitions of

abusive sibling violence put forward by Caffaro and Meyers and respondents’

descriptions of sibling violence in the context of child welfare.

Abusive Sibling Violence in the Context of Child Welfare

While Caffaro and Meyers’ definitions position abusive sibling violence as a form

of child maltreatment, state and federal entities charged with ensuring the safety and

wellbeing of children have largely overlooked this form of family violence. In the United

States, the Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and

Families (ACF) is charged with promoting the economic and social well-being of

families, children, individuals, and communities. ACF programs and services for children

and youth include child abuse and neglect prevention and intervention and ensuring that

children who are victims receive treatment and care. ACF includes the Children’s Bureau

which collects case-level data on reports of child abuse and neglect via the National Child

Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS). Annual analyses of maltreatment data are

summarized in publicly available reports that are also submitted to Congress (U.S.

Department of Health & Human Services, 2015).

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 16

In Child Maltreatment 2016, the 27

th

annual report on child abuse and neglect

generated by the Administration and the most recent report available, child maltreatment

was defined as “Any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker which

results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation; or an

act or failure to act, which presents an imminent risk of serious harm” (U.S. Department

of Health & Human Services, 2016, p. viii). This definition is limited, given that many

people other than parents can be abusers. Regardless, for fiscal year 2016, “there were a

nationally estimated 676,000 victims of abuse and neglect…a rate of 9.1 victims per

1,000 children in the population” (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2016,

p. x). The NCANDS does not capture sibling abuse rates, however, a significant

shortcoming of the system. Children under the age of 18 constitute under one percent of

perpetrators in the NCANDS (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2016, p.

65). Moreover, the system does not disaggregate siblings among the perpetrator

categories captured, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

NCANDS Child Maltreatment Perpetrator Categories and Percentages in 2016

Perpetrator’s Relationship to the Maltreated Child

Percentage

Parent

91.4%

Other relative

4.6%

Unknown

3.1%

Unmarried partner of parent

3.0%

Other

2.7%

More than one nonparental perpetrator

1.1%

Friend or neighbor

.8%

Child daycare provider or other professional

.7%

Foster parent

.2%

Legal guardian

.2%

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 17

According to the NCANDS, sibling perpetrators comprise a very small proportion

of substantiated child maltreatment cases; “other relatives”, who would include a variety

of family members in addition to siblings, account for slightly more than six percent of

perpetrators documented. Foster siblings are subsumed within the “other” category,

which also includes nonrelated adult, nonrelated child, foster sibling, babysitter,

household staff, clergy, and school personnel perpetrators (U.S. Department of Health &

Human Services, 2016, p. 23).

4

These data contrast sharply with numerous other

nationally-representative sources of family violence data. The National Family Violence

Survey, The National Family Violence Resurvey, the Developmental Victimization

Survey and, most recently, the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence

reported rates of severe violence between siblings between 30 and 82 percent annually

(Caffaro, 2011; Finkelhor, Ormrod, Turner, & Hamby, 2005; Gelles & Steinmetz, 2006;

Tucker et al., 2013). While counting violent acts is an overly simplistic approach to

investigating physical abuse and overlooks emotional abuse altogether, it does provide

tangible evidence of the scope of the problem. These general population studies also

support the notion that sibling violence crosses economic boundaries and position

abusive sibling violence as a subset of family violence, comparable to interpersonal

violence between adults and adult-perpetrated child maltreatment with regard to its need

for both attention and intervention. The absence of sibling abuse cases in the NCANDS

4

Data on physical and emotional violence between siblings involved in child welfare are not systematically

collected in any of the three federally-maintained (i.e., national) data systems: National Child Abuse and

Neglect Data System (NCANDS), Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS),

and National Incidence Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS) (Shireman, 2015).

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 18

exposes a lack of alignment between the findings of rigorous, nationally representative

sibling violence research and prevalence tracking conducted through child welfare.

The NCANDS is but one among numerous sources of information highlighting

the lack of attention to abusive sibling violence in child welfare. Many states exclude

sibling maltreatment from definitions of child abuse, or refer to it only indirectly,

influencing both reporting practices and perceptions of what constitutes abuse (Caffaro,

2011). In a state-wide study of child protection service caseworkers conducted in Indiana

in 2004, for example, almost one quarter of the child protection service caseworkers with

an undergraduate degree in social work did not identify physical, sexual, verbal, or

emotional violence when asked how they define sibling abuse (Kominkiewicz, 2008).

5

Without clearly articulated definitions of what constitutes abusive sibling violence, direct

service practitioners are ill-equipped to identify the problem among children they serve.

A focus on the parent as the primary point of intervention may further influence

caseworkers to discount the influence of sibling relationships.

Current child welfare policy recommends that siblings be placed together

whenever possible to support foster youth to maintain sibling ties (McBeath et al., 2014).

There is some evidence that co-placement mediates the relationship between adult-

perpetrated trauma and internalizing and externalizing symptoms among children in

foster care (Hegar & Rosenthal, 2011; Wojciak, McWey, & Helfrich, 2013). At

minimum, co-placement is generally assumed to do no harm (Hegar, 2005). While a

5

This study should be interpreted with caution, as the results were based on a small sample size. It also

appears that abuse was not defined in the survey that was administered to case workers.

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 19

growing body of research has quantitatively assessed the relationship between sibling co-

placement and placement stability, emotional adjustment, and foster children’s

perceptions of their placement situations (Hegar & Rosenthal, 2011), abusive sibling

violence is not discussed (Pinel-Jacquemin, Cheron, Favart, Dayan, & Scelles, 2013).

Oversimplified co-placement policy in the absence of information about harmful sibling

relationships may marginalize cases in which co-placement is not a good idea (Cohn,

2008). In a recent review of the literature on violence among siblings in joint placement,

the authors note a need to refine methodologies and tools used to analyze the

relationships between siblings across the continuum of care (Pinel-Jacquemin et al.,

2013). Linares et al. (2007) argue that separating a foster child from their sibling(s) may

be beneficial under certain conditions (i.e., behavioral or conduct problems).

The need to increase attention to abusive sibling violence in the context of child

welfare is amplified by studies demonstrating high rates of co-occurrence with other

forms of family violence. Children who witness domestic violence between their parents

are more likely to engage in violent behavior with their siblings and peers (Button and

Gealt, 2010; Spaccarelli et al., 1994; Wiehe, 1997). Noland, Liller, McDermott, Coulter,

& Seraphine (2004) found mother-to-father violence, father-to-mother violence, mother-

to-child violence, and father-to-child violence to be significant predictors of sibling

violence perpetration. With regard to the effect of child abuse perpetrated by adult

caregivers, Straus et al. (2006) documented a positive relationship between adult-

perpetrated violence toward a child and that child’s likelihood of severely attacking a

sibling. Children subjected to the most severe abuse from a parent were often intensely

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 20

violent with a brother or sister (National Family Violence Resurvey). Sibling abuse is

also more prevalent in families in which both spousal and child abuse are present

(Wallace, 1999; Wiehe, 1997). Given these findings, it is likely that sibling violence rates

are higher among youth served by the child welfare system than among general samples

(Hamby & Grych, 2013). In support of this notion, a recent study of foster youth found

that acts of extreme sibling violence were commonplace (Linares, 2008).

Abusive Sibling Violence Trauma

The lack of attention to abusive sibling violence in child welfare is concerning,

given that low frequency peer violence (i.e., occurring less than four times per year) has

been significantly associated with trauma symptoms in young children (Finkelhor et al.,

2006). The National Scientific Council on the Developing Child has defined “toxic”

stress as “strong, frequent, or prolonged activation of the body’s stress management

system. Stressful events that are chronic, uncontrollable, and/or experienced without

children having access to support from caring adults tend to provoke these types of toxic

stress responses” (2005/2014). As noted previously, Caffaro’s (2011) definition of

abusive sibling violence describes a repeated, “escalating pattern of sibling aggression

and retaliation that parents seem unwilling or unable to stop” (p. 91). This suggests that

sibling violence may cause toxic stress, which has been linked to physical and mental

illness later in life (Shonkoff et al., 2009). In a study cited by Caffaro (2011), “children

who were repeatedly attacked by a sibling were twice as likely as others their age to

demonstrate severe symptoms of trauma, anxiety, and depression, including

sleeplessness, suicidal ideation, and fear of the dark” (Finkelhor et al., 2006). Deleterious

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 21

outcomes also include mental health challenges, conduct disorders, neurotic traits,

suicidal ideation and attempts, and decreased self-esteem (Button and Gealt, 2010;

Caffaro, 2011; Feinberg et al., 2012; Finkelhor et al., 2006; Graham-Bermann & Cutler,

1992, as cited in Caffaro, 2011). As evidenced by these studies, the harmful effects of

abusive sibling violence manifest across the life course.

A Call to Action

Acknowledging that the phenomenon is often overlooked by social work

practitioners, a recent article in Social Work, a National Association of Social Workers

publication, advocated for the “necessary role for social work” in addressing physical and

emotional sibling violence, arguing that “violence against a child, regardless of the

individual perpetrator, is still violence against a child” (Perkins & O’Connor, 2015, p.

91). When siblings are engaged in the child welfare system, and are removed from their

original family, the state takes on the role of parent for those children and must conduct

adequate assessment to determine whether they are demonstrating healthy conflict or

abusive violence. Similarly, the state is responsible to intervene when abusive sibling

violence is taking place, and to ensure that siblings are not co-placed when risk is

eminent.

These findings point to a significant gap in the child welfare system, for the

published literature contains little or nothing about sibling abuse. This is a new idea for

child welfare. Apparently, little is currently being done, in either policy or practice, to

address abusive sibling violence. A recent publication advocated for inclusion of sibling

violence discussion in child abuse and neglect parent education curricula (Shadik at al.,

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 22

2013). This call for attention to abusive sibling violence in family-focused interventions

is aligned with Perkins and O’Connor’s recommendation that “social workers should

evaluate and develop interventions aimed at preventing or ameliorating physical and

emotional violence between siblings” (2016, p. 92). Yet without holistic understanding of

the causal mechanisms underlying sibling violence, interventions for child welfare-

involved siblings are likely to exclude potentially efficacious components or strategies.

The sections to follow present a synthesis of the literature on sibling violence theory and

intervention.

Family Conditions Associated with Sibling Maltreatment

Two seminal, qualitative studies carried out in the late 1990s identified numerous

individual characteristics and family conditions associated with sibling abuse including:

parental physical or emotional unavailability, lack of supervision, differential treatment

of children in the same family such as scapegoating, inappropriate caretaking

expectations placed on older sibling(s), parental acceptance of sibling rivalry as a normal

part of family life, lack of parent intervention during acts of inter-sibling violence,

parental modeling of physically or emotionally abusive behavior, drug or alcohol abuse

in the home, chronic mental or physical illness of parent(s), work or financial strain, and

parental denial of the problem (Caffaro & Con-Caffaro, 1998; Wiehe, 1997).

In addition to parent characteristics or behaviors, those embodied by perpetrators

and victims were also explored. According to Caffaro and Con-Caffaro (1998), offenders

are prone to thinking errors that minimize or distort their behavior, have suffered

victimization themselves, and/or demonstrate deficiencies of impulse control,

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 23

cognitive/developmental deficits, or an inability to empathize with others. Research

psychologists conducting lab-based investigations similarly identified stable personality

characteristics and cognitive processing deficits among aggressive children such as

impulsivity, callous-unemotional traits, narcissism, and a tendency to inaccurately

interpret social cues (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Frick & White, 2008; Kerig & Stellwagen,

2009; Loeber & Stouthhamer-Loeber, 1998). Large developmental, physical, or

intellectual differences between siblings were similarly associated with sibling abuse

(Caffaro & Con-Caffaro, 1998). While emphatic that victim characteristics should not be

used to place blame, Wiehe (1997) indicated that genetically determined physical and

behavioral qualities may make a child more prone to abuse.

Sibling Violence Theory

Various sources of nationally-representative data indicate that 30 percent or more

of children experience severe violence inflicted by a sibling (Caffaro, 2014; Finkelhor,

Tuner, & Ormrod, 2006; Straus, Gelles, & Steinmetz, 2006; Tucker, Finkelhor, Shattuck,

& Turner, 2013). While these studies reveal the extent of the problem, the research

community has yet to agree on the causal mechanisms underlying abusive sibling

violence. Linear and non-linear (i.e., systems-oriented) theories are discussed in the

literature.

Social learning theory. Numerous studies have documented the co-occurrence of

various forms of family violence, drawing linkages between a child’s exposure to

violence and their propensity to inflict violent acts upon others. Children who witness

interpersonal violence between their parents and/or experience adult-perpetrated abuse

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 24

are more likely to engage in violent behavior with their siblings and peers (Button &

Gealt, 2010; Noland et al., 2004; Spaccarelli et al, 1994; Straus et al., 2006; Wallace,

1999; Wiehe, 1997). Social learning theory, based on the process of modeling or

imitation in response to observation, has been offered as an explanatory theory for the

multigenerational transmission of violence in families (i.e., aggression as a learned

behavior). In a seminal study on the imitation process, Bandura et al. (1963)

demonstrated that children who observed adults behaving aggressively toward a plastic

Bobo doll later imitated this behavior in their own play, whereas a comparison group of

children who did not observe aggressive behavior modeled by adults did not engage in

aggressive play toward the doll. Parental demonstrations of aggression may

surreptitiously communicate to children that violence is a morally-just means to resolve

conflict and achieve desired ends in relationship with family members (Caffaro & Con-

Caffaro, 1998; Straus et al., 2006).

Social learning theory also draws upon reinforcement principles in which a

behavior results in receipt of desired rewards. Between siblings, reinforcement could

occur by gaining control of a desired object, receiving parental attention, or through the

pleasurable experience of power resulting from a sibling’s fearful response (Hoffman &

Edwards, 2004). If behaviors are repeated without redirection or punishment, and

continue to produce desirable effects, violence becomes a patterned response (Walker,

1986). In accordance with social learning theory, numerous researchers have proposed

parental modeling as a salient explanation for sibling abuse (Hoffman & Edwards, 2004;

Kiselica & Morrill-Richards, 2007; Straus et al., 2006).

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 25

Radical feminist theory. According to radical feminist theory, male domination

in all sectors of society reflects broadly accepted oppressive attitudes toward women

which have resulted in various forms of gender inequality including male-female

violence (Button & Gealt, 2010; Hoffman & Edwards, 2004; Hoffman et al., 2005;

Weihe, 1997). Research supports the notion that the patriarchal organization of society

contributes to abusive sibling violence. Studies have demonstrated that brothers have the

highest rates of sibling violence, boys tend to commit more serious acts than girls, and

male siblings are more likely to abuse female siblings (Hoffman et al., 2005; Wiehe,

1997). In Steinmetz and Straus’ seminal study of violence in the American family, those

with only male children had consistently more sibling violence than families composed of

only girls, a statistical relationship that increased markedly as children grew older (2006).

More recently, feminist theories have taken on greater breadth, theorized to

include all power differentials between oppressors and oppressed, such as those based on

race, ethnicity, socio-economic status, and age (Wiehe, 1998). This expansion of feminist

theory is particularly useful when examining potential antecedents for violence within

families in that it is more inclusive of the myriad exchanges that can take place among

members. When applied to the problem of sibling abuse, feminist theory can account for

oppressive dynamics occurring as the result of any source of power differential between

children. In such exchanges the perpetrator is positioned as holding greater power and/or

control such as via physical strength, intellectual/emotional maturity, or level of

responsibility (Button & Gealt, 2010; Hoffman & Edwards, 2004). Wiehe (1997)

described sibling violence as generally entailing an older/bigger/more powerful sibling

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 26

abusing a younger/smaller/less powerful one in order to compensate for a perceived lack

or loss of power. For example, an older sibling required to babysit his younger siblings

might use excessive force to enforce bedtime rules (Wiehe, 1997).

Intersectionalities can create tenuous dynamics where the location of power is not

clear cut. In cases where older female siblings advocate for themselves on the basis of

age hierarchy, younger brothers may successfully challenge their authority with greater

physical strength (Hoffman & Edwards, 2004). Regardless of the characteristics of the

individuals involved, the party holding more power within the conflicting dyad gains a

sense of control through the act of overpowering another. Research supports blending

these notions of feminist theory as an explanation for abusive sibling violence.

Quantitative analysis has demonstrated that sibling pairs comprised of an older (and

presumably larger/stronger) brother and younger (i.e., smaller/weaker) sister were at

greatest risk for serious conflict (Graham-Berman et al., 1994).

Conflict theory. With roots in Marxism, conflict theory assumes that humans are

innately self-interested and that societies are prone to scarcity of resources. In tandem,

these human and societal conditions are posited to create dynamics in which people use

violence to resolve conflicts that stem from competing interests (Smith & Hamon, 2012).

Jetse Sprey is the theorist credited with applying conflict theory to families, focusing on

the conditions under which stability and instability occur (Smith & Hamon, 2012).

Sibling jealousy, competition for parental attention, the expectation that siblings share

games, toys, or other valued items, and disagreements over assigned chores have all been

discussed through the lens of conflict theory (Hoffman et al., 2005). Siblings subjected to

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 27

differential treatment are likely to view each other as competitors for tangible resources

and parental attention (Hoffman et al., 2005). Caffaro and Con-Caffaro’s (1998)

determination that parental physical or emotional unavailability and differential treatment

of children (e.g., scapegoating) were family conditions associated with abusive sibling

violence is supported by conflict theory.

Hoffman and Edwards (2004) proposed a theoretical model of sibling violence

and abuse that integrated social learning theory, feminist theory, and conflict theory, in

addition to risk factors addressed in the extant literature (Hoffman and Edwards, 2004).

Based on numerous linear relationships, the model organizes unidirectional lines of

causation between parent and child characteristics, attitudes, and behaviors hypothesized

to produce physical violence and psychological abuse between siblings. Figure 1 depicts

the relationships between the components of the model.

Figure 1. Integrated theoretical model of sibling physical and psychological abuse

(Hoffman and Edwards, 2004, p. 191).

Characteristics of the

Parents’ Relationship

Characteristics of the

Parent-Child

Relationship

Characteristics of the

Sibling Relationship

Individual Attitudes and

Characteristics

Sibling Verbal Conflict

Physical Violence and

Psychological Abuse

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 28

The researchers tested the model with 651 university students via survey methods

with measures of sibling violence were drawn from the Conflict Tactics Scale and

additional variables operationalized by the researchers (Hoffman et al., 2005; Straus,

1979). At each stage of regression analysis gender was a significant factor. Males with

brothers committed more types of sibling violence and more injurious behaviors (e.g.,

choking, using a weapon) than any other type of sibling pair. Favoring assigning chores

to siblings according to traditional gender roles and approval of using physical force in

sibling conflict were positively associated with sibling violence. The authors argued that

the results were supportive of a feminist theoretical explanation for sibling violence.

Social learning theory also garnered consistent empirical support in that arguments and

interpersonal violence between caregivers and adult-perpetrated violence toward children

were independently associated with sibling violence. Finally, parental favoritism was

associated with heightened sibling violence, evidence that conflict theory was also

supported by the model (Hoffman and Edwards, 2005).

An independent study implemented with a statewide sample of public school

students tested the applicability of feminist and social learning theories to explain sibling

abuse (Button and Gealt, 2010). Among more than 8,000 8

th

and 11

th

grade students

surveyed in 2007, 42 percent reported some form of sibling violence. Females were

significantly more likely to report being victimized than males and youth who identified

their parents as abusive to them or to have witnessed adult violence in the home were

significantly more likely to report sibling violence. In addition to generating further

evidence in support of feminist theory and social learning theory, victimization was

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 29

significantly associated with reports of substance use and delinquency in middle and high

school.

The work of Hoffman and Edwards (2004) and Button and Gealt (2010) makes

useful progress, identifying variables in a linear model theorized to predict abusive

sibling violence. While an essential preliminary step, their approach is based on the

dominant methodological orientation of the social sciences, which is implicitly biased

toward a reductionist perception of reality. Analysis seeks to break a construct or process

down into its component parts. Understanding the relationships between them (which are

assumed to be unidirectional and stable) is the focus of the inquiry. By analyzing abusive

sibling violence in this way, the theories and models described in previous sections

oversimplify a complex, synergistic, and dynamic socio-behavioral process. Subsequent

sections discuss one systems-oriented theory and a systems-based model of sibling

violence.

Coercive family process. Applying general systems theory to family behavior,

family systems theory posits that individual members can be accurately understood only

within the context of the whole family, including past generations. Rather than targeting

individual members as the source of dysfunction, the locus of family problems is viewed

as a function of struggle among members. Numerous forces are seen as moving in many

directions simultaneously, with positive and negative feedback loops guiding behavior.

Family members take on defined roles, repeatedly demonstrating a narrow set of

behaviors across situations, resulting in a relative equilibrium of patterned rules of

interaction (Smith & Hamon, 2012). The family is also viewed as contained by a semi-

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 30

permeable boundary with the environment (Crosbie-Burnett & Klein, 2009). The family

system is perceived as the nexus between structure and function (Zwick, 2015). The

structure of the family system is the organization of members; function is the holistic

behavior of the family, including how it relates to its context. The family system is

hypothesized to engage in relatively stable patterns of behavior over time.

Coercion theory was developed by scientists at the Oregon Social Learning

Center and has been the focus of numerous studies of childhood aggressive behavior.

Based on principles of operant conditioning and negative reinforcement, coercion theory

posits that learning occurs through interpersonal exchanges. Members of a dysfunctional

dyad within the family mutually “train” each other in an ongoing process which

reinforces difficult child behavior including aggression (Granic & Patterson, 2006;

Patterson, 1982). Research on coercion theory has largely focused on parents and their

children, studying a process in which caregivers inadvertently reinforce difficult child

behaviors through repeated, cyclical reactions of emotional withdrawal and giving in

(Smith et al., 2014). Children with more frequent behavioral difficulties such as

aggression (and who are therefore more challenging to parent) amplify coercive parenting

practices which in-turn solidify aggression as a child develops (Granic & Patterson,

2006).

Coercion theory can be applied to the whole family system to describe a coercive

family process in which emotional, cognitive, and behavioral feedback loops manifest

within and among multiple family members to produce multi-directional and synergistic

coercive exchanges. Applying the theory in this way includes all dyadic subsystems; just

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 31

as marital conflict is associated with compromised sibling relationship quality, the

parental relationship, or relationships between caregivers and children, may become

strained in the presence of ongoing sibling conflict (Milevsky, 2011). In a coercive

family process, violence between dyads (or triads, etc.) becomes a stable, family-wide

pattern.

Social ecological model of violence. Human behavior is typically discussed as

generated through interactions among personal and contextual factors, such as by the

“person in environment” orientation of social work. One of the more commonly applied

systems-based models is the ecological framework originally developed by

Bronfenbrenner (1979), which organizes society into a set of nested systems that interact

in a synergistic fashion (Figure 2).

6

When applied to the problem of violence, the values

and actions of individuals, families, communities, and society are viewed as both

reflective and generative of each other. Just as nations employ war tactics to secure

global resources and gangs engage in acts of violence to control illegal drug sales within

impoverished communities, family members and siblings use force to resolve

disagreements. The “second wave” of interpersonal violence scholarship has begun to

6

Figure 2 presents a limited set of concepts from Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory of human

development. The “mature” form of bioecological theory focuses on proximal processes at the center of the

Process-Person-Context-Time model. According to the model, proximal processes of progressively

reciprocal interaction between an individual and the persons, objects, and symbols in their immediate

external environment are the “primary mechanisms” in development. The environment, or context, is

comprised of the microsystem (e.g., home, school, or peer group in which the person spends a good deal of

time engaging in activities and interactions), exosystem (i.e., contexts which have important indirect

influences on development), macrosystem (i.e., the broad set of cultural values that encompass the group

under study and influence the developing individual). In the mature model, time is also an essential

element, which is also comprised of micro-, meso-, and macro- subcomponents. For a complete synthesis,

see Tudge, Mokrova, Hatfield, and Karnik (2009).

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 32

examine how mechanisms of violence perpetration co-occur across individuals and

systems (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014; Hamby & Grych, 2013). A

recent study of preschoolers found that father-child physical aggression interacted with

community violence to predict aggression between siblings (Miller, Grabell, Thomas,

Bermann, & Graham-Bermann, 2012).

Figure 2. Ecological model for understanding violence (adapted from the World Health

Organization, 2002, p. 12).

Subsequent sections will discuss interventions designed to address sibling violence at the

micro-, meso-, and macro-levels of the social ecology.

Sibling Violence Interventions

Micro- and meso-level interventions. A variety of interventions have been

developed to train both parents and children to more productively and peacefully navigate

sibling disputes. As early as 1967, clinicians were testing micro-level approaches to

reduce sibling aggression and increase cooperative play (Kramer, 2004). Early

Relationship

Community

Societal

Individual

SIBLING VIOLENCE AND CHILD WELFARE 33

approaches were largely reactive rather than preventative, aimed at eliminating conflict