Non-Regulatory Guidance for Title II, Part A:

Building Systems of Support for Excellent

Teaching and Leading

U.S. Department of Education Non-Regulatory Guidance

Title II, Part A of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965,

as Amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015

S

eptember 27, 2016

Under the Congressional Review Act, Congress has passed, and the President has signed, a

resolution of disapproval of the accountability and State plans final regulations that were published

on November 29, 2016 (81 FR 86076). Because the resolution of disapproval invalidates the

accountability and State plan final regulations, the portions of this guidance document that rely on

those regulations are no longer applicable. The remainder of this document, however, is unaffected

by the resolution of disapproval.

1

Table of Contents

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................... 2

Purpose of this Guidance ................................................................................................................................................. 2

Part 1: Support for Educators ........................................................................................................................................... 3

Multiple Pathways to Teaching and Leading .................................................................................................................. 4

Teacher, Principal, or Other School Leader Preparation Academies ........................................................................... 4

Teacher and School Leader Residencies..................................................................................................................... 7

Alternative Routes .................................................................................................................................................... 8

Preparation Standards and Approval, Certification, Licensure, and Tenure ................................................................ 8

Induction and Mentorship ............................................................................................................................................. 9

Novice Teacher and Principal Induction and Mentorship ........................................................................................... 9

Meaningful Evaluation and Support ............................................................................................................................ 10

Principles for Strong Educator Evaluation and Support Systems .............................................................................. 10

Strong Teacher Leadership .......................................................................................................................................... 12

Leveraging Teacher Expertise and Leadership.......................................................................................................... 12

Transformative School Leadership ............................................................................................................................... 14

Ongoing Professional Learning for Principals and Other School Leaders .................................................................. 14

State-level Activities and Optional Additional Funding ............................................................................................. 15

Principal Supervisors ............................................................................................................................................... 16

Supporting a Diverse Educator Workforce Across the Career Continuum..................................................................... 17

Part 2: Educator Equity ................................................................................................................................................... 18

Equitable Access to Excellent Educators ...................................................................................................................... 18

Attracting and Retaining Excellent Educators in High-Need Schools ............................................................................. 21

Supporting Early Learning Educators: Ensuring All of Our Youngest Learners Start Strong............................................ 24

Part 3: Strengthening Title II, Part A Investments .......................................................................................................... 25

Understanding the Use of Title II, Part A Funding ........................................................................................................ 26

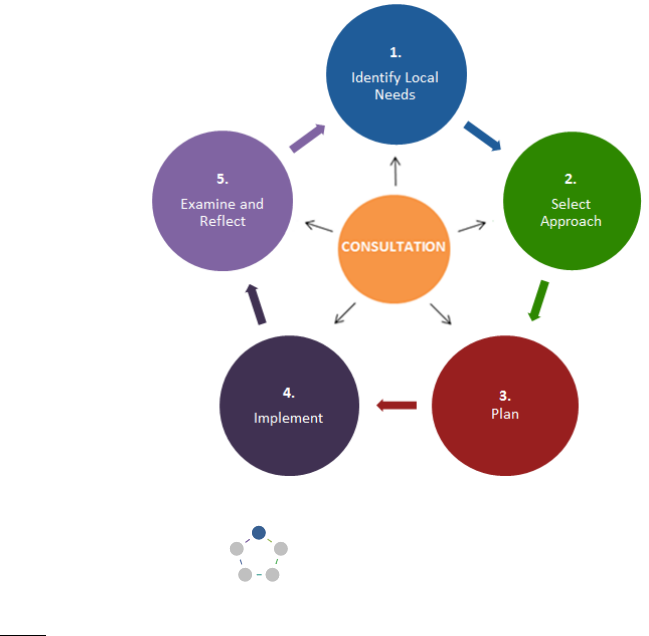

Consultation to Strengthen Title II, Part A Investments ................................................................................................ 26

A Cyclical Framework for Maximizing Title II, Part A Investments................................................................................. 29

Appendix A: Guidance on the Definition of “Evidence-Based” ....................................................................................... 35

Appendix B: Title II, Part A Statutory Language .............................................................................................................. 35

2

The U.S. Department of Education does not mandate or prescribe practices, models, or other activities in this non-

regulatory guidance document. This guidance contains examples of, adaptations of, and links to resources created and

maintained by other public and private organizations. This information, informed by research and gathered in part from

practitioners, is provided for the reader’s convenience and is included here to offer examples of the many resources that

educators, parents, advocates, administrators, and other concerned parties may find helpful and use at their discretion.

The U.S. Department of Education does not control or guarantee the accuracy, relevance, timeliness, or completeness of

this outside information. Further, the inclusion of links to items and examples do not reflect their importance, nor are

they intended to represent or be an endorsement by the U.S. Department of Education of any views expressed, or

materials provided.

State Educational Agencies (SEAs) and Local Educational Agencies (LEAs) must comply with Federal civil rights laws that

prohibit discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, disability, and age. These laws include Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act, the

Equal Educational Opportunities Act (EEOA), Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination

Act of 1975. Further, Section 427 of the General Education Provisions Act (20 U.S.C. §1228a(a)) requires each SEA to

include in its application for Title II, Part A funds a description of the steps the applicant proposes to take to ensure

equitable access to, and participation in, its Federally-assisted program for students, teachers, and other program

beneficiaries with special needs. In addition, LEAs must include this description in their applications to the SEA for Title II,

Part A funds. This provision allows applicants discretion in developing the required description. The statute highlights six

types of barriers that can impede equitable access or participation: gender, race, national origin, color, disability, or age.

Based on local circumstances, SEAs and LEAs should determine whether these or other barriers may prevent their

students, teachers, etc. from such access or participation in, the Federally-funded project or activity.

3

Introduction

Great teachers, principals, and other school leaders (collectively, educators) matter enormously to the learning and the

lives of children.

1

Yet, we have struggled as a nation to meaningfully support educators so they can help their students

be prepared to succeed in college and careers. The Title II, Part A program is designed, among other things, to provide

students from low-income families and minority students with greater access to effective educators. It is critical that

State educational agencies (SEAs) and local educational agencies (LEAs) consider how to best use Title II, Part A funds,

among other funding sources, to ensure equity of educational opportunity. New provisions in Title II, Part A of the

Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (ESEA), as amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), offer

new opportunities SEAs and LEAs to more effectively attract, select, place, support, and retain excellent educators; re-

visit traditional uses of these funds; and consider new and additional uses of Title II, Part A funds that are innovative and

evidence-based.

Strategies outlined in this document, and examples of this work in action, can often be supported by other sources of

funding as well, and should not be thought of as tools, policies or programs only made possible through the use of Title

II, Part A funds. States and districts are encouraged to explore sources of funding available at the State and local level, as

well as other formula and competitive grant awards from the U.S. Department of Education and other sources. This

initial Title II, Part A guidance is not exhaustive; rather it highlights some of the new and important ways SEAs and LEAs

can use their Title II, Part A funds

more strategically and for greater impact. This initial guidance also reflects

feedback the Department received from States, districts, and a variety of other stakeholders and educators, during

listening sessions regarding high-priority areas for guidance related to these funds. Throughout this guidance, any

reference to “educators” refers to teachers, principals, and other school leaders. Unless otherwise indicated, citations to

the ESEA refer to the ESEA, as amended by the ESSA.

Purpose of this Guidance

The U.S. Department of Education (Department) has determined that this guidance is significant guidance under the

Office of Management and Budget’s Final Bulletin for Agency Good Guidance Practices, 72 Fed. Reg. 3432 (Jan. 25,

2007). See www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/memoranda/fy2007/m07-07.pdf. Significant guidance is non-

binding and does not create or impose new legal requirements. The Department is issuing this guidance to provide SEAs

and LEAs with information to assist them in meeting their obligations under Title II, Part A provisions. This guidance also

provides members of the public with information about their rights under the law and regulations.

This guidance supersedes the Department’s previous guidance on Title II, Part A of the ESEA as amended by the No Child

Left Behind Act (NCLB), entitled Improving Teacher Quality State Grants, issued on October 5, 2006.

If you are interested in commenting on this guidance, please email us your comment at

OESEGuidanceDocument@ed.gov or write to us at the following address:

U.S. Department of Education

Office of Elementary and Secondary Education

400 Maryland Avenue, S.W.

Washington, D.C. 20202

For further information about the Department’s guidance processes, please visit

www2.ed.gov/policy/gen/guid/significant-guidance.html.

1

Teachers Matter: Understanding Teachers' Impact on Student Achievement. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2012.

http://www.rand.org/pubs/corporate_pubs/CP693z1-2012-09.html

; B. Rowan, R. Correnti, & R. J. Miller (2002). “What Large-Scale Survey Research

Tells Us About Teacher Effects on Student Achievement: Insights from the Prospects Study of Elementary Schools. Teachers College Record, 104:

1525-1567; S.G. Rivkin, E. Hanushek, & J.F. Kain (2000). “Teachers, Schools, and Academic Achievement (Working Paper W6691).” National Bureau

of Economic Research. Retrieved from www.cgp.upenn.edu/pdf/Hanushek_NBER.PDF

4

Part 1:

Support for Educators

High-quality teaching and learning requires a diverse cohort of educators, including teachers, principals, and other

school leaders, to be prepared and supported to meet the many challenging demands that they and their students face,

particularly underserved students and students of color. The continuum of the educator profession and associated

opportunities to support educators, from recruitment through career advancement, may be viewed broadly as five

interrelated steps that build upon one another. There are many opportunities to use Title II, Part A funds to develop new

ways to support educators at various points in this continuum, as well as augment and strengthen existing efforts to

improve individual parts and the overall system of supports. While not exhaustive, this section highlights important

opportunities to support educators, while acknowledging that Title II, Part A funds alone likely are not enough to fully

address and support the entire educator career continuum. Additional information that is helpful in understanding how

Title II, Part A investments can be strengthened is included in Part 3 of this guidance.

Multiple

Pathways to

Teaching and

Leading

Induction and

Mentorship

Meaningful

Evaluation and

Support

Strong Teacher

Leadership

Transformative

School

Leadership

5

Multiple Pathways to Teaching and Leading

Most LEAs obtain the majority of their new teachers from traditional preparation programs at IHEs; in many States,

some LEAs also are able to obtain new teachers through alternative sources. When considering its support of various

pathways into teaching and school leadership, an SEA and LEA should first understand how well these differing sources

meet educators’ and students’ needs. Title II, Part A funds may be used to support both traditional and non-traditional

pathways through the development of new teacher, principal, or other school leader preparation academies, teacher

and principal residencies and other alternative routes. Additionally, Title II, Part A funds may be used to support the

effective recruitment, selection, and hiring of the most promising educators; additional information on this topic is

included in Part 3 of this guidance.

Teacher, Principal, or Other School Leader Preparation Academies

Under ESEA section 2101(c)(4)(B)(xii), from the amount the SEA reserves for State-level activities (without consideration

of additional funds that would otherwise be provided in LEA subgrants, and that it may use under section 2101(c)(3) for

principal and other school leader activities), an SEA may use up to 2 percent of the State’s total Title II, Part A State

allocation) to establish or expand teacher, principal, or other school leader preparation academies to prepare teachers,

principals, and other school leaders to serve in high-need schools. Under ESEA section 2101(c)(3), an SEA may also

reserve up to an additional 3 percent of the total amount available for LEA subgrants to support activities for principals

or other school leaders. Therefore, an SEA may reserve a maximum of 4.85 percent of the State’s Title II, Part A total

State allocation to establish or expand academies that train and support principals or other school leaders. For more

information, see Understanding Title II, Part A Flow of Funding Chart in Part 3 (page 26) of this Guidance document.

Academies allow SEAs to create outcomes-based training programs for educators, including early educators, which are

based on innovative best practices and rigorous case-studies, and are directly responsive to needs SEAs identify among

their LEAs. Under ESEA section 2002(4), an academy may be established by a public or other nonprofit entity, including

an IHE or an organization affiliated with an IHE. To use Title II, Part A State activities funds to establish or expand an

academy, the Governor must first designate a State authorizer consistent with ESEA section 2002(3) that will enter into

an agreement with an academy that specifies the academy’s expected goals.

Multiple

Pathways to

Teaching and

Leading

Induction and

Mentorship

Meaningful

Evaluation and

Support

Strong Teacher

Leadership

Transformative

School

Leadership

6

While these State authorizers would be new, States can look to other types of authorizers, such as charter school

authorizers, for best practices. Though not a perfect analogue to the role the state authorizer will play with these

academies, some resources to consider include: The National Alliance of Charter School Authorizer's (NACSA) Principles

and Standards, and NACSA’s 12 Essential Practices. The Council for Higher Education Accreditation also has resources

that may be worth considering.

Then, the SEA may use Title II, Part A funds to support a teacher, principal, or other school leader academy

that, consistent with the requirements of ESSA:

(1) Enters into an agreement with the State authorizer that includes:

(a) A requirement that prospective candidates receive a significant part of their training through clinical

preparation that includes partnerships with effective educators, as determined by the State, with a

demonstrated record of increasing student academic achievement, while also receiving concurrent

instruction from the academy in the content area in which the candidates will become certified or licensed

that links to the clinical preparation experience;

(b) Data on the number of educators who will demonstrate success in increasing student academic

achievement that the academy will prepare;

(c) A requirement that the academy will award a certificate of completion to a teacher only after the teacher

demonstrates that the teacher is an effective teacher, as determined by the State, with a demonstrated

record of increasing student academic achievement either as a student-teacher or teacher of record on an

alternative certificate, license or credential;

Recommended Strategies

Some strategies to consider when designating a State authorizer include:

Developing and participating in a community of practice among State education leaders, to support

the creation of principles and standards for effective academy authorization, which should be

informed by best practices regarding the preparation of effective educators.

Adopting a publicly transparent performance framework for how the state will evaluate and hold

accountable the authorizer, considering such things as the rigor of its ongoing monitoring and

oversight process; the extent to which the authorizer holds academies accountable for

performance; and how performance data of academies is shared with the public.

Identifying and articulating “essential practices” for the authorizer to use, such as external expert

panels, initial term lengths, renewal criteria, annual reporting, etc.

Establishing outcome-oriented performance metrics to facilitate oversight by the authorizer and

provide common expectations and standards for academies. This may include developing rigorous

qualifications for teacher and/or principal candidates to successfully complete the program, such as

demonstration of cultural competency, classroom management skills, subject area and content-

specific knowledge, and the ability to use standards-based, data-driven and differentiated

instruction.

7

(d) A requirement that the academy will award a certificate of completion to a principal or other school leader

only after the principal or other school leader demonstrates a record of success in improving student

performance; and

(e) Timelines for producing cohorts of graduates and conferring certificates of completion. (ESEA section

2002(4)(A)).

(2) Does not unnecessarily restrict the methods the academy will use to train prospective candidates, including

restrictions on:

(a) Specific faculty credentials or responsibilities;

(b) The academy’s physical infrastructure;

(c) Required course credits;

(d) The undergraduate coursework of teachers; and

(e) The academy’s accreditation. (ESEA section 2002(4)(B)).

(3) Limits admission to prospective candidates who demonstrate strong potential to improve student academic

achievement, based on a rigorous selection process that reviews a candidate’s prior academic achievement or

record of professional accomplishment. (ESEA section 2002(4)(C)).

(4) Ensures that successful completion results in a certificate of completion or degree that may be recognized by the

State as at least the equivalent of a master’s degree in education for the purposes of hiring, retention,

compensation, and promotion after a State’s review of the academy’s results in producing effective candidates.

(ESEA section 2002(4)(D)).

The State must also:

(1) Ensure that an academy is allowable under State Law. (ESEA section 2101(c)(4)(B)(xii)(I)).

(2) Allow candidates attending an academy to be eligible for State financial aid to the same extent as participants in

other State-approved teacher or principal preparation programs, including alternative certification, licensure, or

credential programs. (ESEA section 2101(c)(4)(B)(xii)(II)).

(3) Allows candidates who are teaching or working while on alternative certificates, licenses, or credentials to teach or

work in the State while enrolled in an academy. (ESEA section 2101(c)(4)(B)(xii)(III)).

Additional resources to consider when designing teacher, principal, or other school leader academies include those from

Deans for Impact and The Council for Chief State School Officers: From Chaos to Coherence: A Policy Agenda for

Accessing and Using Outcomes in Educator Preparation, and Our Responsibility, Our Promise: Transforming Educator

Preparation and Entry into the Profession.

8

Teacher and School Leader Residencies

SEAs and LEAs may also use Title II, Part A funds to establish, improve, or support school-based residency programs for

teachers and school leaders. Teacher residency programs must, for at least one academic year, provide prospective

teachers: (a) significant teaching experience working alongside an effective teacher of record; and (b) concurrent

instruction by LEA personnel or faculty of the teacher preparation program in the content area in which the teachers will

become certified or licensed. In addition, the residencies must provide prospective teachers with effective teaching skills

as demonstrated through completion of the residency program or other indicator as determined by the State. (ESEA

section 2002(5), 2101(c)(4)(B)(xi), 2103(b)(3)(B)). School leader residency programs must, for at least one academic

year, provide prospective principals or other school leaders: (a) sustained and rigorous clinical learning in an authentic

school setting; (b) evidence-based coursework, to the extent the State determines in consultation with LEAs that

evidence is reasonably available; (c) ongoing support from an effective mentor principal or school leader; (d) substantial

leadership responsibilities; and (e) an opportunity to practice and be evaluated in a school setting. (ESEA sections

2002(1), 2101(c)(4)(B)(xi), 2103(b)(3)(C)). SEA residency programs may be implemented in conjunction with a State

agency of higher education consistent with ESEA section 2101(c)(4)(A).

SEAs may consult several resources to better understand how they may use teacher and school leader residencies to

address equitable access challenges when preparing teachers. One example is the Urban Teacher Residency report,

highlighted in a webinar, entitled Teacher Residency Programs Improve Access to Excellent Educators.

Alternative Routes

SEAs may also use their Title II, Part A State activities funds to support programs that establish, expand, or improve

alternative routes to State certification for educators, especially for teachers of children with disabilities, English

learners, STEM subjects, or other areas where the State experiences a shortage of educators. (ESEA section

2101(c)(4)(B)(iv)). There are several resources that SEAs may consult when considering options for designing and

improving alternative pathways to certification including a policy brief issued by GTL: Alternative Routes to Teaching:

What Do We Know About Effective Policies?. See also the Department’s Strengthening Principal Prep Progress Blog for

additional resources.

Pathways in Action: Clinical Experience in a Teacher Residency Program

Many organizations have created effective teacher residency programs. For example, California State

University, Dominguez Hills, has

developed Lab Schools that their Urban Teacher Residency program

candidates participate in as part of their year-long clinical residency. Through a partnership with local high-

need LEAs, Lab School sessions are held twice a month on Saturday and during the summer. Students from the

partner high-

need LEAs attend the Lab Schools, which in the past have provided science, technology,

engineering, and math (STEM) courses the LEAs otherwise may not have been able to offer, to receive extra

academic support. Simul

taneously, the residents are observed and coached by experienced mentor teachers,

and sometimes school principals, to help them improve their pedagogical and classroom management skills.

An external evaluation of the 2013-2014 Saturday and summer Lab Schools, reported positive outcomes for

student learning, through pre- and post-tests;

and teacher candidates showed high levels of satisfaction,

reporting that in particular they valued, ”the exposure to different teaching styles, having the opportunity to

collaborate, as well as obtaining feedback from lead teachers and interacting with students.”

9

Through alternative routes to State certification, LEAs may fill educator shortages, such as those for teachers of children

with disabilities, English learners, or teachers of STEM subjects, by recruiting individuals who, though not trained in a

traditional preparation program, have the potential to become effective teachers, principals, or other school leaders.

(ESEA section 2103(b)(3)(C)). These individuals may come from widely diverse backgrounds – for example, individuals

who already have Bachelor’s or advanced degrees, mid-career professionals, paraprofessionals, former military

personnel, and other recent IHE graduates with records of academic distinction.

Preparation Standards and Approval, Certification, Licensure, and Tenure

Under ESEA section 2101(c)(4)(B)(i), SEAs may use Title II, Part A funds to support reform efforts with the entities that

oversee preparation standards and approval, certification, licensure, and tenure in order to ensure that:

Teachers have the necessary subject-matter knowledge and teaching skills in the academic subjects that they teach

to help students meet challenging State academic standards (as demonstrated through measures determined by the

State, which may include teacher performance assessments);

Principals or other school leaders have the instructional leadership skills to help teachers teach and to help students

meet challenging State academic standards; and

Teacher certification or licensing requirements are aligned with challenging State academic standards.

Induction and Mentorship

Novice Teacher and Principal Induction and Mentorship

SEAs and LEAs are encouraged to use Title II, Part A funds to establish and support high quality educator induction and

mentorship programs that where possible are evidence-based and are designed to improve classroom instruction and

Multiple

Pathways to

Teaching and

Leading

Induction and

Mentorship

Meaningful

Evaluation and

Support

Strong Teacher

Leadership

Transformative

School

Leadership

Pathways in Action: Developing Local Pipelines of Teachers

Many LEAs have created local teacher pipeline programs. For example, Teach Tomorrow in Oakland (TTO),

developed by Oakland Unified School District

, is a program that complements candidates receiving alternative

certification through higher education teache

r preparation programs by creating a pathway into teaching for

new educators, most of whom are recruited locally and are people of color from minority groups that are

underrepresented in the teaching profession. The program has focused significant attentio

n on removing

barriers associated with becoming a teacher; TTO has developed partnerships with local community colleges to

enable teacher candidates to take additional coursework necessary for certification, and offers test preparation

support and funding

to cover the costs of State certification exams. Using a cohort model to provide additional

peer and mentor support for candidates after completion, TTO has achieved a 3-

year retention rate of 79% for

its teachers.

10

student learning and achievement and increase the retention of effective teachers, principals, or other school leaders.

(ESEA sections 2101(c)(4)(B)(vii)(III) and 2103(b)(3)(B)(iv)). Research shows that high-quality induction and mentoring

programs can increase teacher retention as well as increase student achievement. For instance, comprehensive

induction programs can cut the new teacher turnover rate in half.

2

Additionally, students of novice teachers who

experienced strong induction “in general, achieve in patterns that mirror the achievement rates of students assigned to

more experienced mid-career teachers.”

3

Taking into account the high cost of teacher turnover, investments in

mentoring and induction programs not only benefit students and teachers, but also reduce costs for LEAs and SEAs. Title

II, Part A funds may be used to support a mentoring and induction program by providing early release time for

mentoring, compensation for mentors, and evidence-based professional development for novice educators and

mentors.

SEAs and LEAs should consider many factors when designing and implementing educator mentorship and induction

programs, including potential partners that can support these efforts, such as educator preparation programs. In

particular, partnerships with educator preparation programs can provide continuity for novice teachers’ transitions into

the classroom, as well as offer educator preparation programs the opportunity to align their programs with the needs of

LEAs.

There are several resources that identify factors to consider in developing such programs, including the New Teacher

Center report Support from the Start: A 50-State Review of Policies on New Educator Induction and Mentoring, which

includes recommendations such as:

Requiring that all beginning teachers and principals receive induction support during their first two years.

Requiring a rigorous mentor/induction coach selection process.

Establishing criteria for how and when mentors/induction coaches are assigned to beginning educators, and

determining the training they will receive to serve in this role.

Requiring regular observation by mentors/induction coaches and opportunities for new teachers to observe

classrooms.

4

Additional resources on educator mentorship and induction include REL: Central Region’s How Do School Districts

Mentor New Teachers? and GTL’s The Excellent Educators for All Initiative: Connecting State Priorities with Practical

Induction and Mentoring Strategies

.

2

A. Kaiser & F. Cross (2011). “Beginning Teacher Attrition and Mobility: Results from the First through Third Waves of the 2007-08 Beginning

Teacher Longitudinal Study.” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education: National Center for Education Statistics.

http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2011/2011318.pdf

3

A. Villar & M. Strong (2007). Is Mentoring Worth the Money? A Benefit-Cost Analysis and Five-year Rate of Return of a Comprehensive Mentoring

Program for Beginning Teachers. Educational Research Service, (25)3: 1-17.

4

L. Goldrick (2016). “Support from the Start: A 50-State Review of Policies on New Educator Induction and Mentoring.” The New Teacher Center.

https://newteachercenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016CompleteReportStatePolicies.pdf

11

”

Meaningful Evaluation and Support

Principles for Strong Educator Evaluation and Support Systems

The Department encourages SEAs and LEAs to establish and continuously improve human capital management systems,

including educator evaluation and support systems. Title II, Part A funds may be used by SEAs and LEAs to develop,

implement, and improve rigorous, transparent, and fair evaluation and support systems if these systems are based in

part on evidence of student achievement, which may include student growth, and must: (1) include multiple measures

of educator performance, such as high-quality classroom observations, and (2) provide clear, timely and useful feedback

to educators. (ESEA sections 2101(c)(4)(B)(ii) and 2103(b)(3)(A)).

Well-designed and implemented educator evaluation and support systems will:

Continually improve instruction: The primary goal of educator evaluation and support systems is to support

instructional improvement and inform opportunities for educators to grow and improve. Evaluation and support

systems should generate frequent, timely, and actionable feedback for educators. Training evaluators, including

principal evaluators, in both assessing educators and providing meaningful feedback is critically important.

Supplementing that feedback with additional support in the form of ongoing, job-embedded professional

development opportunities is critical to ensuring that educators have access to the necessary resources and

opportunities to improve their practice. SEAs, LEAs, and schools should consider what structures, capacity, and

leadership will be necessary to incorporate on-going professional development opportunities for educators into

their systems of evaluation and support. ESEA section 8101(42) defines “professional development,” specifically

noting that the professional development activities are sustained (not stand-alone, 1-day, or short term

workshops), intensive, collaborative, job-embedded, data-driven, and classroom-focused. Educator evaluation

Multiple

Pathways to

Teaching and

Leading

Induction and

Mentorship

Meaningful

Evaluation and

Support

Strong Teacher

Leadership

Transformative

School

Leadership

Induction in Action: Providing Local Context through Induction Programs

Many entities have created effective induction programs. For example, the

Urban Center at Illinois State

University

, in partnership with Chicago Public Schools, Peoria School District, and Decatur Public Schools, has

developed a summer immersion opportunity for their pre-bac

calaureate teacher preparation program,

Teacher+PLUS. To increase teacher candidates’ investment in serving in these schools and communities upon

graduation, and to support their understanding of the cultural context and needs of local students, the

program made changes to the content of their coursework and began providing pre-service teacher

candidates the opportunity to spend the summer months prior to their formal clinical experience living with

and learning from local families and community-based organ

izations. These teacher candidates also gain

practical experience working with students by participating in tutoring and other academic enrichment

programs. An external evaluation of the Teacher+PLUS program found that the redesigned coursework and

clinica

l experience showed a “statistically significant positive impact on teacher candidates' initial attitudes

towards their intentions to teach in urban areas and their attitudes towards working within diverse urban

cultural communities ”

12

and support systems should not be used as a mechanism to put teachers into binary positive or negative categories,

but rather to help educators improve.

Meaningfully involve educators and other stakeholders: Educator support and evaluation systems should directly

connect to opportunities for educators to improve instruction. As such, educators should be involved in the

development and implementation of evaluation and support systems. Educator expertise in the innovation and

improvement of these systems is critical to successful implementation and may include, for example, encouraging

teachers to design measures for the overall evaluation and support systems.

Be valid, reliable, and fair: To be effective, educator evaluation and support systems should be technically and

educationally sound, and implemented by well-trained educators and administrators. Generally SEAs and LEAs

should convene technical advisory committees that include experts in assessment of student growth and other

educator evaluation measures to help SEAs determine the most appropriate measures to include in their systems, as

well as to suggest the types of training and resources that districts will need for successful implementation. Even

with a valid, reliable, and fair system, the decision to dismiss an educator should never be made on the basis of a

single test score or a lone evaluation rating.

Include multiple measures: Educator evaluation and support systems supported with Title II, Part A funds must

include multiple measures. (ESEA sections 2101(c)(4)(B)(ii) and 2103(b)(3)(A)). No single measure can provide a

comprehensive assessment of an educator’s contribution, and so multiple measures are necessary.

- Observations, along with other measures of professional practice, are at the heart of most systems, and

research shows that short, frequent, formative observations by multiple well-trained observers lead to a more

complete and accurate picture of an educator’s practice

5

. Supervisors, independent observers, peers, or a

combination of individuals across these categories can conduct observations and provide feedback. Consistent

with ESEA sections 2101(c)(4)(B)(ii) and 2103(b)(3)(A), Title II, Part A funds may be used to train and support

observers.

- If SEAs or LEAs choose to use Title II, Part A funds for educator evaluation and support systems, the systems

must be based in part on evidence of student academic achievement. (ESEA sections 2101(c)(4)(B)(ii) and

2103(b)(3)(A)). One common way that SEAs and LEAs measure student academic achievement is by looking at

the growth students achieved between two points in time for the students in a teacher’s classroom or a

principal’s school. Measuring growth, instead of point-in-time achievement, allows every teacher to have the

opportunity to excel, by giving credit for student learning no matter where students were at the beginning of

the year. Student growth may be measured using changes in State assessment results, when available, or

changes in results on other kinds of assessments. Often, evaluation systems require educators to set growth

goals (sometimes called student learning objectives (SLOs)) for students and measure results using local

assessments, rubric-based reviews of student work portfolios, or another method of judging student

performance against the goal in a consistent manner.

- Including additional measures, such as parent, teacher, and student perception/satisfaction surveys can also

provide teachers and leaders with valuable feedback that can be used to inform their practice. The following

resources may be useful to consider: Multiple Choices: Options for Measuring Teacher Effectiveness

from the

Rand Corporation, Missouri Department of Education Surveys, and Gathering Feedback for Teaching from the

Gates Foundation.

5

E. Taylor & J. Tyler (2012). "The Effect of Evaluation on Teacher Performance." American Economic Review, 102(7): 3628-51.

13

Be transparent: The inputs, outputs, and outcomes of educator evaluation and support systems should be

transparent and comprehensible. Educators should participate in the development and implementation of

evaluation and other human capital plans. All teachers and school leaders should have a clear understanding of the

metrics on which they are being evaluated before the data collection process begins, as well as confidence that

evaluation scores will be used to support professional development that will ultimately help educators better serve

their students. Educators should have access to their individual performance measures, not just their summative

ratings. Resources should be readily available for educators to access in order to improve in areas they and their

evaluators jointly identify as areas of need. Clear processes and procedures should also be in place for educators to

dispute results they think are unfair.

Help ensure educational equity: The Department shares with SEAs and LEAs the goal of ensuring that the most

vulnerable students in the highest-need schools have access to excellent teachers and leaders. To realize this goal,

educator evaluation and support systems should be put in place – whether funded by Title II, Part A or other sources

– to identify excellent teachers and leaders as an important first step towards ensuring that all students have equal

access to them. See Part 3 for more information on Educator Equity.

Some resources that may be helpful in developing, implementing, and improving evaluation and support systems

include: GTL’s State Teacher and Principal Evaluation Policies; Educator Evaluation Tools; and Brief: Alternative

Measures of Teacher Performance; and TNTP’s Teacher Evaluation 2.0.

Strong Teacher Leadership

Leveraging Teacher Expertise and Leadership

Sustainable teacher career paths should give teachers the opportunity to exercise increased responsibility and to grow

professionally, while keeping effective teachers in the classroom. Moreover, the availability of teacher leadership

opportunities positively impacts teacher recruitment and retention, job satisfaction, and student achievement.

6

With the recommended strategies below, and all other permissible activities, Title II, Part A funds may be used to

support “time banks” or flexible time for collaborative planning, curriculum writing, peer observations, and leading

trainings; which may involve using substitute teachers to cover classes during the school day. (ESEA sections

2101(c)(4)(B)(v) and 2103(b)(3)(E)). Furthermore, funds may be used to compensate teachers for their increased

leadership roles and responsibilities. (ESEA sections 2101(c)(4)(B)(vii)(I) and 2103(b)(3)(B)).

6

C. Natale, L. Gaddis, K. Bassett, &K. McKnight (2016). “Teacher Career Advancement Initiatives: Lessons Learned from Eight Case Studies.”

Pearson and the National Network of State Teachers of the Year.

http://www.nnstoy.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/RINVN829_Teacher-

Career-Adv-Initiatives_Rpt_WEB_f.pdf

Multiple

Pathways to

Teaching and

Leading

Induction and

Mentorship

Meaningful

Evaluation and

Support

Strong Teacher

Leadership

Transformative

School

Leadership

14

Recommended Strategies

Title II, Part A funds may be used for a full range of activities to better leverage and support teacher

leadership, for example:

Career opportunities and advancement initiatives for effective teachers that promote professional

growth and emphasize multiple career paths. This includes creating hybrid roles that allow instructional

coaching of colleagues while remaining in the classroom, as well as assuming other responsibilities such as

collaborating with administrators to develop and implement distributive leadership models and leading

decision-making groups. (ESEA sections 2101(c)(4)(B)(vii)(I) and 2103(b)(3)(B));

Supporting peer-led, evidence-based

1

professional development in LEAs and schools. (ESEA sections

2101(c)(4)(B)(v)(I) and 2103(b)(3)(E));

Recruiting and retaining talented and effective educators, including mentoring new educators.

(ESEA sections 2101(c)(4)(B)(v) and 2103(b)(3)(B));

Participating in community of learning opportunities and other professional development

opportunities with diverse stakeholder groups such as parents, civil rights groups, and administrators, to

positively impact student outcomes; for example, through a forum to discuss the implication of a policy or

practice on a school community, or organizing a community-wide service learning project, where teachers

afterwards work together to imbed conclusions of these activities into their teaching. (ESEA sections

2101(c)(4)(B)(vii) and 2103(b)(3)(E)).

Teacher Leadership in Action: Learning From Teacher Leaders

Many LEAs have developed effective professional learning programs to support teacher leadership. For

example, educators from the Albuquerque Public Schools (ABQ)

, working in coalition with the National

Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBP

TS) Network to Transform Teaching, are leveraging the

knowledge and expertise of National Board certified teachers (NBCTs) as leaders to bridge the gap between

professional learning and classroom practice. The ABQ-NBCT project is developing and deepening a shared

understanding of how educator leadership provides the strongest possible educational environment for

students and promotes student learning. Educational stakeholders from across the State have been involved

with learning about the work of the teach

er leaders and strategizing about supporting their endeavors.

Stakeholders pledged significant commitments that will amplify and expand the lesson study model both

within ABQ and Educational stakeholders from across the State have been involved with learning about the

work of the teacher leaders and strategizing about supporting their endeavors. Stakeholders pledged

significant commitments that will amplify and expand the lesson study model both within ABQ and across

other school districts.

15

Transformative School Leadership

Ongoing Professional Learning for Principals and Other School Leaders

Effective principals, assistant principals, and other school leaders are essential to school success, particularly in schools

with large numbers of students from low-income families and minority students

7

. Strong principals attract teachers with

great potential for success, support the ongoing professional learning of teachers, and retain excellent teachers.

A resource on how SEAs and LEAs may produce a large and steady supply of high-performing school principals and

support their effective supervision is The Wallace Foundation’s Building Principal Pipelines: A Strategy to Strengthen

Education Leadership. An additional resource that SEAs and LEAs may consider when selecting evidence-based

interventions related to school leadership is School Leadership Interventions under the Every Student Succeeds Act from

RAND Corporation. This report describes opportunities for supporting school leadership, discussing the standards of

7

See for example K. Leithwood (2004). “How Leadership Influences Student Learning.” The Wallace Foundation.

http://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/pages/executive-summary-how-leadership-influences-student-learning.aspx

Multiple

Pathways to

Teaching and

Leading

Induction and

Mentorship

Meaningful

Evaluation and

Support

Strong Teacher

Leadership

Transformative

School

Leadership

Recommended Strategies

SEAs and LEAs may use Title II, Part A funds to support school principals, through a variety of strategies such

as:

Partner with organizations to provide leadership training and opportunities for principals and other

school leaders to hone their craft and bring teams together to improve school structures. (ESEA sections

2101(c)(4)(B)(viii) and 2103(b)(3)(B)).

Offer community of learning opportunities where principals and other school leaders engage with their

school teams to fully develop broad curriculum models. (ESEA sections 2101(c)(4)(B)(viii) and

2103(b)(3)(E)).

Develop opportunities for principals and other school leaders to collaborate, problem-solve, and share

best practices. (ESEA sections 2101(c)(4)(B)(viii) and 2103(b)(3)(E)).

16

evidence, and synthesizing the research with respect to those standards.

State-level Activities and Optional Additional Funding

Under Title II, Part A of the ESEA, SEAs have broad authority and flexibility in the use of State activities funds. SEAs

may use some of these funds to improve the quality and retention of effective teachers. However, we strongly

encourage each SEA to devote a significant portion of its State activities funds to improving school leadership; and in

doing so consider its flexibility to reserve an additional 3 percent of Title II, Part A LEA subgrants for States activities

that support principals or other school leaders. (ESEA section 2101(c)(3)).

Leadership in Action: Supporting Promising Principals

Many LEAs have developed effective supports for individuals transitioning into school leadership roles. For

example, the Maryland Department of Education has developed a program for Promising Principals to

provide promising leaders, most of whom are assistant principals, with a year-long professional development

program that includes multi-day convenings, one-on-one coaching sessions with veteran principals, and the

opportunity to receive feedback as

they tackle challenges they will likely face as principals. In addition, the

veteran principals that participate as coaches, selected due to their track records of success, have found that

they gain professional development through this experience in coaching emerging leaders.

Recommended Strategies

In addition to the examples of principal support activities identified above, SEAs have significant discretion

when deciding how to use their State activities funds to support principals and school leaders. Allowable

activities include:

Reforming school leader certification, tenure systems, or preparation program standards and approval

processes, so that school leaders have the instructional leadership skills to help teachers teach and

students achieve (ESEA section 2101(b)(4)(B)(i));

Developing or improving alternative pathways to school leadership positions (ESEA section

2101(b)(4)(B)(iv);

Helping LEAs implement school leader evaluation and support systems that are based in part on evidence

of student academic achievement (ESEA section 2101(b)(4)(B)(ii));

Helping LEAs recruit and retain school leaders who are effective in improving student academic

achievement through means that include differential and performance pay for principals in low-income

schools and districts (ESEA sections 2101(b)(4)(B)(v) and (vii)); and

Developing new school leader evidence-based mentoring, induction, and other professional development

programs for new school leaders (ESEA section 2101(b)(4)(B)(vii) and (viii)).

17

Principal Supervisors

When developing strategies for supporting principals and other school leaders, SEAs and LEAs may use Title II, Part A

funds to improve the effectiveness of principals, assistant principals, and other school leaders, which includes an

employees or officers of an elementary or secondary school, LEA, or other entity operating a school who are

“responsible for the daily instructional leadership and managerial operations in the elementary school or secondary

school building.” (ESEA section 8101(44)).

By including principal supervisors who are responsible for the daily instructional leadership and managerial operations in

the elementary school or secondary school building, the ESEA section 8101(44) definition of “school leader”

acknowledges the importance of school leaders who are actively responsible for successful instruction and management

in the school. This means that the ESEA considers those LEA staff, such as the principals’ supervisors, who actively

mentor and support principals and by doing so are themselves “responsible for the school’s daily instructional leadership

and managerial operations,” to also be eligible for Title II, Part A funded support. (ESEA section 8101(44)). We encourage

SEAs and LEAs to extend Title II, Part A-funded services to these principal supervisors to the extent that those individuals

actively and frequently take responsibility for helping principals with instructional leadership and the school’s

managerial operations.

Supporting a Diverse Educator Workforce Across the

Career Continuum

Research shows that diversity in schools, including representation of underrepresented minority groups among

educators, can provide significant benefits to all students

8 9

. In addition to benefits for all students, improving the

8

N. Tyler, Z. Yzquierdo, N. Lopez-Reyna, & S. Saunders Flippin (2004). "Cultural and Linguistic Diversity and the Special Education Workforce: A

Critical Overview." The Journal of Special Education, 38(1): 22-38.

Multiple

Pathways to

Teaching and

Leading

Induction and

Mentorship

Meaningful

Evaluation and

Support

Strong Teacher

Leadership

Transformative

School

Leadership

Leadership in Action: Supporting Principal Supervisors

Principal supervisors enable principals to focus on improving instruction, rather than on administration and

compliance. Some LEAs, such as Tulsa Public Schools (TPS) and District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) are

investing in and expanding the importance of this position and have rethought the principal supervisor’s job.

TPS and DCPS give supervisors fewer schools to oversee to ensure they can provide adequate and individualized

support for principals. The result is that principal supervisors are now fixtures in schools, conducting classroom

walkthroughs to observe strengths and areas for growth, providing timely and meaningful feedback to

principals, and helpi

ng to develop solutions to challenges. To truly support the role of the principal supervisor,

LEAs must treat the position as critical and provide effective professional development for individuals filling this

role. Under ESEA sections 2101(c)(4)(B)(vii)

and 2103(b)(3)(B), Title II, Part A funds can be used to support

those principal supervisors that actively and frequently take responsibility for helping principals with

instructional leadership and the school’s managerial operations.

18

diversity of the educator workforce may be particularly beneficial for minority students

10

helping to close the

achievement gap. When considering how to better support educators, SEAs and LEAs should consider supporting a

diverse educator workforce as a critical component of all strategies across the career continuum (for example, as framed

by this Part 2). Relevant resources include the Department’s report: The State of Racial Diversity in the Educator

Workforce and GTL’s blog post: States Can Lead on Teacher Recruitment Pipelines.

SEAs and LEAs may use Title II, Part A funds to improve the recruitment, placement, support, and retention of culturally

competent and responsive educators, especially educators from underrepresented minority groups, to meet the needs

of diverse student populations.

9

A. Egalite, B. Kisida, & M. Winters (2015). “Representation in the Classroom: The Effect of Own-race Teachers on Student Achievement.”

Economics of Education Review, 45: 44-52; T. Dee (2004).“Teachers, Race, and Student Achievement in a Randomized Experiment." The Review of

Economics and Statistics, 86: 195-210.

10

J. Grissom & C. Redding (2016). “Discretion and Disproportionality: Explaining the Underrepresentation of High-Achieving Students of Color in

Gifted Programs,” AERA Open, 2: 1–25; A. M. Villegas & J. J. Irvine (2010). “Diversifying the Teaching Force: An Examination of Major Arguments."

The Urban Review, 42: 175–192.

19

Recommended Strategies

Under ESEA sections 2101(c)(4)(B)(v) and 2103(b)(3)(B), these efforts may include, but are not limited

to:

Providing financial support to educator recruitment programs within the community to improve

hiring and retention of a diverse workforce;

Offering career advancement opportunities for current staff members, such as paraprofessionals,

who have worked in the community for an extended period of time, to support their efforts to gain

the requisite credentials to become classroom instructors;

Partnering with preparation providers including local community colleges, Institutions of Higher

Education (IHEs), Minority Serving Institutions, and alternative route providers, to build a pipeline

of diverse candidates;

Providing ongoing professional development aimed at cultural competency and responsiveness and

equity coaching, designed to improve conditions for all educators and students, including educators

and students from underrepresented minority groups, diverse national origins, English language

competencies, and varying genders and sexual orientations;

Providing time and space for differentiated support for all teachers, including affinity group

support;

Supporting leadership and advancement programs aimed to improve career and retention

outcomes for all educators, including educators from underrepresented minority groups; and

Developing and implementing other innovative strategies and systemic interventions designed to

better attract, place, support, and retain culturally competent and culturally responsive effective

educators, especially educators from underrepresented minority groups, such as having personnel

or staff-time dedicated to recruiting diverse candidates of high-quality who can best teach to the

diversity of the student population.

Although efforts to recruit a diverse workforce may not be limited on the basis of race,

differentiation of supports for educators from diverse backgrounds is permissible.

20

Part 2:

Educator Equity

To ensure that every student has access to excellent educators, SEAs and LEAs must work together to develop, attract,

and retain excellent educators in all schools, especially in high-need schools. Part of the purpose of the Title II, Part A

program is to provide students from low-income families and minority students greater access to effective teachers,

principals, and other school leaders. (ESEA section 2001). To realize this outcome, SEAs and LEAs are strongly

encouraged to use Title II, Part A funds to improve equitable access to effective teachers. (ESEA sections

2101(c)(4)(B)(iii) and 2103(b)(3)(B)).

21

Equitable Access to Excellent Educators

The Title II, Part A program is designed, among other things, to provide students from low-income families and

minority students with greater access to effective teachers, principals, and other school leaders. Under ESEA sections

1111(g)(1)(B) and 1112(b)(2), SEAs must describe how low-income and minority children are not served at

disproportionate rates by ineffective, out-of-field or inexperienced teachers and identify and address any disparities

that exist in the rates at which these students are taught by teachers in these categories. To eliminate any such

disparities, an SEA and its LEAs should develop and implement strategies that are responsive to the root causes of those

disproportionate rates; Title II, Part A funds can be used -- and in certain cases may be directed -- to provide students

from low-income families and minority students with greater access to effective teachers, principals, and other school

leaders.

The most effective strategies are designed to support the students for whom there are the greatest rates of

disproportionality in access to excellent educators, while also addressing the underlying factor or factors causing or

contributing to these disproportionalities.

For example, SEAs and LEAs in which students from low-income families are taught at higher rates by inexperienced

teachers may discover that this is driven by a lack of teacher retention in rural areas. Such SEAs and LEAs may consider

developing “grow your own” initiatives, through which resources are devoted to recruiting local talent to counteract

teacher shortages, particularly in high-need schools in rural areas, because teachers who grew up in a particular rural

area are more likely to stay there over the long term

11

. These initiatives, which exist in urban areas as well as rural areas,

often involve partnering with local high schools and IHEs to promote education as a career pathway and may include

experiential learning opportunities in high-need schools.

Depending on the root causes identified by an SEA or LEA for the absence of excellent educators, the SEA or LEA may

also want to consider making strategic investments in data systems to ensure that decision-makers have ready access to

comprehensive, timely, and high-quality data. These data would help to inform decisions and target resource

allocations. In a case where the root cause analysis demonstrated that appropriate incentives were not in place to help

ensure that excellent educators are attracted to and remain in high-need schools, Title II, Part A funds could be used to

incentivize and reward excellent educators serving in an SEA’s or an LEA’s highest-need schools. An SEA or an LEA might

further consider implementing specific initiatives designed to increase the diversity of its educator workforce. For

example, they might support an initiative to increase the number of pre-college students from underrepresented

minority groups who are interested in education careers, by helping them to become certified to teach, and supporting

them to ultimately become effective educators that are recruited and hired. (ESEA sections 2101(c)(4)(B)(iii) and (v)).

SEA Tools to Ensuring Equitable Access to Effective Educators

11

G. Bornfield, N. Hall, P. Hall, & J. H. Hoover (1997).” Leaving Rural Special Education: It's a Matter of Roots.” Rural Special Education Quarterly,

16(1), 30–37; T. Collins (1999). “Attracting and Retaining Teachers in Rural Areas.” Retrieved July 26, 2016, from World of Education,

http://library.educationworld.net/a8/a8–102.html

To help ensure the purposes of Title II, Part A are met, an SEA may require an LEA to describe how it will

provide students from low-income families and minority students with greater access to effective teachers,

principals, and other school leaders in its local Title II, Part A application. (ESEA sections 2001 and 2102(b)).

22

As with other programs and consistent with the General Education Provisions Act, an SEA has the authority to require

changes before approving an LEA’s application for Title II, Part A funds if an LEA fails to address local application

requirements. (ESEA section 2102(b)). The LEA application review process is among the most significant levers available

to each SEA. When well-implemented, this process can help ensure that each LEA faithfully implements the ESEA’s

requirements. Consequently, the Department encourages each SEA to invest in robust LEA application design, review,

and approval systems. In the context of Title II, Part A, this means that an SEA’s LEA application review systems and

processes should be sufficient to identify any LEA application that inadequately addresses how that LEA will meet the

purposes of Title II, Part A, including how the LEA will ensure that students from low-income families and minority

students have greater access to effective teachers, principals and other school leaders. SEAs should require an LEA to

address any existing deficiencies prior to its receipt of Title II, Part A funds. SEAs should also carefully consider an LEA’s

local context and needs. As part of this consideration, an SEA should consider meaningful input from a variety of

stakeholders, including those stakeholders that will be instrumental in deploying an LEA’s strategies to eliminate existing

equity gaps.

Proposed Educator Equity Requirements

To support SEAs and LEAs in providing students from low-income families and minority students greater access to

effective teachers, principals, and other school leaders, on May 31, 2016, the Department published an NPRM in the

Federal Register regarding an SEA’s authority to direct an LEA to use Title II, Part A funds to promote educator equity.

Under proposed § 299.18(c)(7)(i), an SEA may direct an LEA to use a portion of its Title II, Part A funds to provide low-

income and minority students greater access to effective teachers, principals, and other school leaders, provided that it

does so in a manner that is consistent with the allowable activities outlined in ESEA section 2103. Additionally, under

proposed §299.18(c)(7)(ii), an SEA may require an LEA to describe how it will use Title II, Part A funds to address any

identified equity gaps. Please note that these regulations are proposed. The comment period for the NPRM closed on

August 1, 2016. The Department is in the process of finalizing the regulations and intends to provide further guidance

when the regulations are final.

Equity in Action: Examples of Innovative Plans to Increase Equitable Access to Effective Educators

Missouri – Missouri is focusing on correcting its imbalance of teacher supply and demand in hard-to-staff

content areas and geographic locations by developing and implementing an educator Shortage Predictor

Model. This Shortage Predictor Model pinpoints where educator shortages will likely occur by region and

certification area across the State, so that Missouri can target its recruitment and retention efforts in a

way that helps to minimize educator shortages and, ultimately, helps to ensure that all of Missouri’s

students will have access to excellent educators. Additional information about Missouri’s Educator Equity

Plan can be accessed here.

Delaware – In order to address gaps related to teacher turnover in high-need schools, Delaware is

examining ways to implement differentiated compensation opportunities for educators and create career

pathways, one of which is a Teacher-Leader Pilot in the 2016-2017 school year, which will provide

teachers with career development opportunities without requiring them to leave the classroom.

Additional information about Delaware’s Educator Equity Plan can be accessed here.

23

Additional resources on how SEAs and LEAs can help ensure students have equitable access to excellent educators

include: The Education Trust - Achieving Equitable Access to Strong Teachers: A Guide for District Leaders; and The

Equitable Access Support Network - Resources on Equitable Access Topics Areas.

Attracting and Retaining Excellent Educators in High-Need Schools

Between the 2011-12 and 2012-13 school years, 22 percent of teachers in high-poverty schools either moved to another

school or left the profession, a rate that is roughly 70 percent higher than in low-poverty schools.

12

In addition to higher

turnover, one study found that four times as many math and science teachers transfer from high-poverty schools to low-

poverty schools than transfer from low-poverty schools to high-poverty schools.

13

Given these statistics and the urgency

of students’ needs in high-poverty schools, SEAs and LEAs need bold approaches that fundamentally change the nature

of the teaching job in these schools and change it in ways that are responsive to what teachers say are needed in order

to attract and keep a diverse set of talented educators.

12

2012-13 NCES Teacher Follow-up Survey https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/sass/tables/TFS1213_2014077_cf1n_002.asp; the percentage of

“movers” and “leavers” in schools with 75 percent or more of students approved for free or reduced-price lunch was 22 percent, compared to

12.8 percent in schools with 0-34 percent of students approved for free or reduced-price lunch.

13

2012-13 NCES Teacher Follow-up Survey https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/sass/tables/TFS1213_2014077_cf1n_002.asp; the percentage of

“movers” and “leavers” in schools with 75 percent or more of students approved for free or reduced-price lunch was 22 percent, compared to

12.8 percent in schools with 0-34 percent of students approved for free or reduced-price lunch.

Recommended Strategies

To realize the equity goals of the ESEA, Title II, Part A funds may be used by LEAs in high-need schools to:

Create incentives for effective educators to teach in high-need schools, and ongoing incentives for

such educators to remain and grow in such schools. (ESEA section 2103(b)(3)(B)).

Develop and implement initiatives to assist in recruiting, hiring, and retaining effective teachers to

improve within-district equity, particularly in districts that are not implementing districtwide reforms,

such as initiatives targeted to high-need schools that provide (ESEA section 2103(b)(3)(B)):

- Expert help in screening candidates and enabling early hiring;

- Differential and incentive pay for educators in high-need schools, which may include

performance-based compensation systems;

- Differential and incentive pay for teachers in high-need academic subject areas and specialty

areas (e.g., serving English learners and children with disabilities), which may include

performance-based compensation systems;

- Educator advancement and professional growth and an emphasis on leadership

opportunities, which may include hybrid teacher/leader and leadership positions, multiple

career paths, pay differentiation and incentives for effective educators to receive additional

certifications in high-need areas;

- Co-teaching of classes, especially co-teaching by an experienced effective teacher and a

novice teacher.

24

Recommended Strategies (Continued)

- New educator induction or mentoring programs designed to improve classroom instruction

and student learning and achievement and increase the retention of effective educators;

- Many of the other strategies highlighted earlier in this document with a focus on the

highest-need schools.

- Development and provision of training for school leaders, coaches, mentors, and evaluators

on how to accurately differentiate performance, provide useful feedback and use evaluation

results to inform decision-making about professional development, improvement strategies

and personnel decisions;

Develop feedback mechanisms to improve working conditions, including through periodically and

publicly reporting results of educator support and working conditions feedback which may

leverage teacher leadership and community partners. (ESEA section 2103(b)(3)(N)).

Carry out in-service training for school personnel in addressing issues related to school conditions

for student learning, such as safety, peer interaction, drug and alcohol abuse, and chronic

absenteeism. (ESEA section 2103(b)(3)(I)(iv)).

Create teams of educators for teachers in high-need schools who convene regularly to learn,

problem solve, and look over student work together, or provide time during the school day for

educators to observe one another and reflect on new teaching and leading practices. A recent

Department blog entry,

Top Atlanta Teachers Put Good Teaching on Display, describes one

approach to innovative use of time.

Provide “teacher time banks” to allow effective teachers and school leaders in high-need schools

to work together to identify and implement meaningful activities to support teaching and learning.

For example, when implementing teacher time banks, Title II, Part A funds may be used to pay the

costs of additional responsibilities for teacher leaders, use of common planning time, use of

teacher-led developmental experiences for other educators based on educators’ assessment of

the highest leverage activities, and other professional learning opportunities. (ESEA sections

2101(c)(4)(B)(v)(I) and 2103(b)(3)(E)(iv) and reasonable and necessary cost principles in 2 CFR §

200.403).

Improve working conditions for teachers through high-impact activities based on local needs, such

as improving access to educational technology, reducing class size to a level that is evidence-

based, to the extent the State determines that such evidence is reasonably available, or providing

ongoing cultural proficiency training to support stronger school climate for educators and

students. (ESEA sections 2103(b)(3)(B), (D) and (E)).

25

Supporting Early Learning Educators: Ensuring All of Our Youngest Learners Start Strong

The ESEA explicitly includes new ways SEAs and LEAs may use Title II, Part A funds to support early learning so that all

children, no matter their zip code, begin kindergarten ready to succeed. Title II, Part A funds may be used to support the

professional development of early educators. These funds have a wide variety of possible applications for early

educators and the ESEA explicitly includes new ways SEAs and LEAs may use Title II, Part A funds to support early

learning.

Recommended Strategies

Title II, Part A funds may be used by SEAs and LEAs for the following strategies:

For the first time, allowing LEAs to support joint professional learning and planned activities

designed to increase the ability of principals or other school leaders to support teachers, teacher

leaders, early childhood educators, and other professionals to meet the needs of students

through age eight. (ESEA section 2103(b)(3)(G)). The National Academy of Medicine’s

Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation offers

recommendations to build a workforce that is unified by the foundation of the science of child

development and early learning and the shared knowledge and competencies that are needed to

provide consistent, high-quality support for the development and early learning of children from

birth through age eight.

Supporting LEAs to increase the knowledge base of teachers, principals, or other school leaders

regarding instruction in the early grades and developmentally appropriate strategies to measure

how young children are progressing. (ESEA section 2103(b)(3)(G)). Leading Pre-K-3 Learning

Communities: Competencies for Effective Principal Practice (Executive Summary), from the

National Association of Elementary School Principals, defines new competencies, and outlines a

practical approach to high-quality early childhood education that is critical to laying a strong

foundation for learning for young children from age three to third grade.

Supporting LEA training on the identification of students who are gifted and talented, and

implementing instructional practices that support the education of such students, including early

entrance to kindergarten. (ESEA section 2103(b)(3)(J)).

Allowing SEAs to support opportunities for principals, other school leaders, teachers,

paraprofessionals, early childhood education program directors, and other early childhood

education program providers (to the extent the State defines elementary and secondary

education to include preschool; explained further in the Early Learning Guidance) to participate in

joint efforts to address the transition to elementary school, including issues related to school

readiness. (ESEA section 2101(c)(4)(B)(xvi)).

26

Part 3:

Strengthening Title II, Part A

Investments

The Title II, Part A program is designed to increase student achievement; improve the quality and effectiveness of