Prepared by a joint team comprised of

Era Dabla-Norris, Ruud de Mooij, Andrew Hodge,

Jan Loeprick, Dinar Prihardini, Alpa Shah,

Sebastian Beer, Sonja Davidovic,

Arbind Modi, and Fan Qi

Digitalization and

Taxation in Asia

Asia-Pacic and Fiscal Affairs Departments

DP/2021/017

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Digitalization and

Taxation in Asia

Prepared by a joint team from the IMF Asia-Pacic and Fiscal Aairs

Departments, comprised of Era Dabla-Norris, Ruud de Mooij,

Andrew Hodge, Jan Loeprick, Dinar Prihardini, Alpa Shah,

Sebastian Beer, Sonja Davidovic, Arbind Modi, and Fan Qi

Asia-Pacific and Fiscal Affairs Departments

Copyright ©2021 International Monetary Fund

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

IMF Library

Names: Dabla-Norris, Era, project director. | Mooij, Ruud A. de, project director. |International Monetary

Fund. Asia and Pacic Department, issuing body. | International

Monetary Fund. Fiscal Aairs Department, issuing body. | International Monetary Fund, publisher.

Title: Digitalization and taxation in Asia / prepared by a joint team from the IMF Asia-Pacic and Fiscal

Aairs Departments, led by Era Dabla-Norris and Ruud de Mooij.

Other titles: International Monetary Fund. Asia and Pacic Department (Series). | International Monetary

Fund. Fiscal Aairs Department (Series).

Description: Washington, DC : International Monetary Fund, 2021. | Departmental paper series. | “Prepared

by a joint team from the IMF Asia-Pacic and Fiscal Aairs Departments, led by Era Dabla-Norris and

Ruud de Mooij, and comprising Andrew Hodge, Jan Loeprick, Dinar Prihardini (coordinator), Alpa Shah,

with contributions from Sebastian Beer, Sonja Davidovic, Arbind Modi, and Fan Qi. Research assistance was

provided by Hibah Khan and Biying Zhu. Soa Cerna Rubinstein supported the production of the paper.” |

Includes bibliographical references.

Identiers: ISBN 9781513577425

Subjects: LCSH: Technological innovations—Economic aspects—Asia. | Taxation—Asia. | Tax administration

and procedure—Asia.

Classication: LCC T173.8 D33 2021

Prepared by a joint team from the IMF Asia-Pacic and Fiscal Aairs Departments, led by Era Dabla-Norris

and Ruud de Mooij, and comprising Andrew Hodge, Jan Loeprick, Dinar Prihardini (coordinator), Alpa Shah,

with contributions from Sebastian Beer, Sonja Davidovic, Arbind Modi, and Fan Qi. Research assistance was

provided by Hibah Khan and Biying Zhu. Soa Cerna Rubinstein supported the production of the paper.

Publication orders may be placed online, by fax, or through the mail:

International Monetary Fund, Publication Services

P.O. Box92780, Washington, DC 20090, U.S.A.

Tel. (202) 623-7430 Fax: (202) 623-7201

E-mail: [email protected]

www.imfbookstore.org

www.elibrary.imf.org

is joint Asia-Pacic–Fiscal Aairs Departmental Paper presents research by IMF sta on issues of broad

regional or cross-country interest. e views expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not

necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

Contents

Glossary ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������v

Executive Summary ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� vii

Introduction �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1

1� Digitalization in Asia ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 5

Asia’s ICT Sector ............................................................................................................ 6

Digitalization Beyond the ICT Sector ............................................................................6

How Is Digitalization in Asia Dierent? ........................................................................9

2� Income Tax for Highly Digitalized Businesses in Asia––Challenges and a Way

Forward �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 17

Challenges of Taxing Digitalized Businesses in Asia .....................................................17

Multilateral Reform ......................................................................................................18

Digital Services Taxes ...................................................................................................24

Alternative Policy Options ...........................................................................................34

3� Digital Services, Digitally Delivered Goods, and VAT ��������������������������������������������� 43

Digital Services in Asia .................................................................................................44

Policy Options and Country Practices..........................................................................45

Revenue Potential .........................................................................................................49

Annex 1� Methodology �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 55

Annex 2� Detailed Formulary Apportionment Results �������������������������������������������������� 59

References ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 61

Boxes

Box 1. Amazon and Alibaba––Comparison between an American and Asian Tech

Giant ......................................................................................................................14

Box 2. India’s Equalization Levy ..................................................................................40

Box 3. Ensuring Taxation of Intermediary Fees ............................................................51

Box 4. GST Compliance Mechanism for Supply of Digital Services by MNEs in

the Case of India .................................................................................................... 52

Tables

Table 1. Residual Prot by Headquater Jurisdiction, 2017...........................................20

Table 2. Residual Prot and Other Descriptive Statistics by Sector, 2017 ....................21

iii

Table 3. Digital Services Taxes in Asia ..........................................................................25

Table 4. e Economic Impact of DSTs ......................................................................28

Table 5. VAT on Digital Services––Approaches in Asia-Pacic ....................................46

Figures

Figure 1. A Digitalized Economy ...................................................................................6

Figure 2. Asia’s ICT Sector .............................................................................................7

Figure 3. Internet Access in Asia ....................................................................................8

Figure 4. E-Commerce in Asia .......................................................................................9

Figure 5. Asian Sales of E-Commerce Companies ........................................................10

Figure 6. Global Market Share: E-Commerce Companies ...........................................10

Figure 7. Turnover of Asia’s Tech Giants ......................................................................11

Figure 8. Sales, Productivity, and Prots of Asia’s Tech Giants .....................................11

Figure 9. Income Tax Expensed ...................................................................................12

Figure 10. Growth of Asia’s Tech Giants ......................................................................13

Figure 11. Top 20 Locations of Residual Prot ............................................................22

Figure 12. Potential Revenue Eects of Pillar 1, Amount A .........................................23

Figure 13. Facebook: Active Users and Average Revenue Per User ...............................30

Figure 14. Survey-Based Estimates of the Tax Base and Revenue Potential in 2019 ..... 31

Figure 15. MNE Activities at Home and Abroad and the Destination of Asian

MNE Prots ..........................................................................................................33

Figure 16. Change in Income Tax Revenue from Applying FA ....................................36

Figure 17. Total CIT Revenue Eects from Destination-Based RPA ............................36

Figure 18. Partial CIT Revenue Eects—from Elimination of Prot Shifting .............38

Figure 19. Partial CIT Revenue Eects—from Reallocation of Residual Earnings ....... 39

Figure 20. Increase in Digitally Delivered Services and Demand for Digital Media ..... 45

Figure 21. Survey-Based Estimates of Direct VAT Revenue Potential and VAT

Eciency in Asia....................................................................................................50

iv

DIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIADIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIA

Glossary

ADS Automated Digital Service

B2B Business to Business

B2C Business to Consumer

BEPS Base Erosion and Prot Shifting

CbCR Country by Country Reporting

CIT Corporate Income Tax

Destination country Country in which the purchaser is located (same as

market country)

DST Digital Services Tax

EL Equalization Levy

EU European Union

FA Formula Apportionment

FDI Foreign Direct Investment

G20 e G20 is the international forum that brings

together the world’s major economies

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GST Goods and Services Tax

ICT Information and Communications Technology

IF Inclusive Framework

Investment Hub Generally refer to countries with a high ratio of FDI

to GDP. For example, the OECD considers those

countries with inward FDI greater than 150 percent

of GDP to be an investment hub.

Market country Country in which the purchaser is located (same as

destination country)

IGST Integrated Goods and Services Tax

MNE Multinational Enterprise

OECD Organisation for Economic Cooperation and

Development

v

OIDAR India is chargeable on supply of Online Information

Database Access and Retrieval

PE Permanent Establishment

Prot shifting Shifting of where prots are booked for tax purposes,

and encompasses base erosion

Rents Earnings in excess of the normal required return

Residence country For a corporation (most frequently the location of

managerial functions; occasionally the place of

incorporation)

Residual prot Prots in excess of routine

Routine return Broadly equivalent to normal return, commonly as

identied by transfer pricing methods

RP Residual Prot

RPA Residual Prot Allocation

Source country Jurisdiction in which production of goods or services

occurs

User participation Contribution by the user of the product to the busi-

ness model

VAT Value-Added Tax

DIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIADIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIA

vi

Executive Summary

Digitalization in Asia is pervasive, unique, and growing. It stands out by

its sheer scale, with internet users far exceeding numbers in other regions.

is facilitates e-commerce in markets that are large by international stan-

dards, supported by innovative payment systems and featuring major cor-

porate players, including a number of large, home-grown, highly digitalized

businesses (tech giants) that rival US multinational enterprises (MNEs) in

size. Opportunity for future growth exists, as a signicant population share

remains unconnected.

Digitalization raises new tax challenges and existing rules can be perceived as

unfair. Existing income tax systems have been criticized as failing to con-

fer taxing rights on jurisdictions where highly digitalized businesses have a

large base of customers that generate value, but where they have no physical

presence. Increasingly digitalized businesses may also have relatively more

intangible assets (for example, trademark and patents), which are harder to

value and easier to relocate, enabling prot shifting under existing rules. is

may especially aect smaller, less developed economies. e nexus of digitali-

zation and tax also goes beyond income taxation, raising issues regarding the

eective value-added taxation of digital services, property rights over private

information, and the use of digital technology in tax design and revenue

administration.

Global tax reform proposals will create winners and losers in the region,

although the overall revenue impact is likely to be modest. New taxing rights

for market countries at the expense of residence countries, along the lines of

proposals discussed under Pillar 1 of the OECD-Inclusive Framework (IF)

will change the geographic distribution of tax revenue paid by MNEs in Asia.

Investment hubs and low-tax jurisdictions are likely to lose revenue as less

prot will be shifted towards them. Countries that do not host the headquar-

ters of large MNEs, but have a large user base of their customers, are likely to

gain revenue from the reallocation. Results are more ambiguous for countries

vii

that have both a large market and tax residence for large MNEs. For exam-

ple, the home countries of Asia’s tech giants could lose revenue if these rms

have to pay more tax in other countries where they are expanding. While

the revenue eects are likely to be modest for most countries under current

proposals, the rapid pace of digitalization can increase the importance of this

revenue reallocation eect over time.

Digitalization is increasing pressure on the century-old international tax

framework, which more fundamental reforms could address in the medium

term. e reforms currently being considered in the OECD-IF could be

a step toward more comprehensive reforms in the future. Systems that are

being discussed among tax experts include, for example, formulary appor-

tionment and residual prot allocation. ese approaches would cause a

much larger reallocation of tax revenue across countries, with the largest

losses expected for investment hubs. At the same time, these proposals could

deliver considerable simplication and closer alignment of prot attributions

to where production and sales take place. Depending on the design, these

reforms could also ease the pressure of international tax competition and

provide scope for increasing revenue raised from MNEs, including through

an increase in CIT rates as desired by countries.

Unilateral tax measures, such as digital services taxes (DSTs), adopted by a

number of Asian countries are likely to have small revenue eects. DSTs are

simpler in design and implementation than corporate income tax initiatives,

but risk introducing distortions of double taxation and trade retaliation. In

taxing gross revenue, they are blind to the protability of the ring-fenced

tech giants and therefore less ecient than alternative prot taxation reform

options. Countries with domestic tech giants may nd a DST less attractive

as the income of these rms is already taxed under the existing CIT regime.

A relatively narrow gross revenue tax base also results in limited revenue col-

lection—often estimated in the range of 0.01-0.02 percent of GDP, suggest-

ing that the choice to introduce a DST needs to be weighed against other tax

reform priorities. at said, revenue from DSTs may have higher buoyancy in

the future, given strong growth of digital economic activity, a trend that has

been accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Extending the value added taxes (VAT) to capture e-commerce and digi-

tal services more eectively could yield signicant short-term revenue and

other eciency gains. Capturing VAT on digitally provided services and

e-commerce supplied from abroad will help countries increase revenue

unilaterally. Applying VAT consistently on all digital imports also levels the

playing eld between domestic and foreign suppliers, and between goods

and services—thus enhancing eciency. e expected revenue eects from

eectively doing so are greater than from DSTs or the global reform proposal

currently under consideration under OECD-IF Pillar 1, in particular when

accounting for indirect returns from relying on marketplaces as a third party

DIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIADIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIA

viii

information source and as collection agents to expand the VAT base. ere is

scope to leverage administrative reforms in VAT on digital imports to sup-

port both the compliance management of residents and the implementation

of corporate tax reforms that shift taxing rights to the market country for

non-residents.

For many Asian countries, additional eorts in taxation are necessary to meet

their revenue mobilization needs. International tax reform towards greater

destination-based income taxation in combination with a global minimum

tax (Pillar 2 of the OECD-IF) would ease pressures from international tax

competition and allow countries to raise corporate income tax rates if desired.

Further revenue mobilization eorts might be required to nance future

spending needs. ese could focus on broadening the tax base by remov-

ing tax holidays, exemptions, and other preferential tax treatments. ese

are common in developing Asia but are often ineective and inecient and

could even become redundant under a global minimum tax. Digitalization of

tax administrations could further help revenue mobilization by addressing tax

evasion and widen the tax base for corporate taxes and VAT. Such compre-

hensive tax reforms, however, go beyond the scope of this paper.

Executive Summary

ix

Digitalization has been impacting countries in Asia and this eect is set

to grow in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Digitalization has

extended well beyond the information communications and technology

(ICT) sector, with widespread internet usage underpinning e-commerce,

ntech, as well as online nancial and other services. In addition to rms

selling goods and services through their own websites, online platforms and

marketplaces have rapidly emerged that connect rms with consumers and

consumers with each other. ese business models are supported by cutting

edge technologies, including articial intelligence, machine learning, and big

data. Local rms have emerged as major players, particularly in large mar-

kets such as China, Japan, and Indonesia, competing with US multinational

enterprises (MNEs) operating in the region. e potential for further growth

in internet usage and the shift away from in-person activities during the

pandemic is likely to fuel the growth of large, digitalized businesses in Asia

in coming years, as well as the adoption of digital technologies across the

entire economy.

e experience of digitalization varies across Asian countries depending on

demographics, geography, and the stage of economic development. G20

economies such as China, Japan and Korea have large ICT sectors, including

manufacturing, and well-established, locally headquartered, highly digitalized

businesses engaging in e-commerce and online services. India and Indonesia

are also rapidly developing markets for e-commerce and online services, with

emerging local rms. Advanced services-based economies such as Australia

and New Zealand are highly digitalized, although ICT-led manufacturing is

less prevalent. Additionally, Asia has city states that are hubs for ICT sec-

tor businesses and ntech, such as Singapore. In contrast, developing Asian

economies have lower rates of internet connectivity and are less likely to have

large, locally headquartered digitalized rms.

Introduction

1

e ability of highly digitalized rms to make cross-border sales without a

physical presence challenges traditional corporate income tax (CIT) rules.

ese rules give taxing rights over corporate prots to countries where rms

are headquartered and where they have a permanent establishment (for exam-

ple, factory or storefront). For highly digitalized businesses trading online

across borders, this can mean that the countries where sales are made (market

countries), or where online users are located have no taxing rights over the

rm’s income. ere are also challenges for countries with taxing rights under

existing rules because the assets of highly digitalized rms can be more con-

centrated in intangibles (for example, intellectual property) compared with

other businesses. Intangible assets can be more easily transferred to related

members of a corporate group in lower tax jurisdictions, allowing prot to be

shifted away from a country with higher tax rates.

Cross-border online sales of goods and services also place pressure on value

added tax (VAT) collection. ere is broad agreement across countries that

VAT should be paid where the nal consumer resides (see for example, the

OECD’s VAT/GST guidelines 2017). is is increasingly dicult to imple-

ment in a digitalized economy as VAT collections largely rely on locally regis-

tered rms remitting the tax. Enforcing VAT collection on, for example, the

purchase of online streaming services from a non-resident supplier is much

more challenging.

Multilateral discussions to resolve the challenges of taxing income in an

increasingly digitalized economy are conducted under the auspices of the

G20/OECD Inclusive Framework (IF). e IF consists of 139 members,

including the major Asian economies and many developing countries. Under

the so-called Pillar 1, countries are discussing a proposal to provide a new

taxing right to market jurisdictions, thus addressing the concern around tax-

ing rights in a digitalized economy.

1

While awaiting agreement in the IF, some countries have begun imple-

menting digital services taxes (DSTs), which typically tax the receipts of

non-resident rms from sales made to their residents. DSTs can take the form

of simple withholding taxes on payments (for example, for online advertis-

ing), similar to existing taxes on cross-border technical services. Alternatively,

they can be in the form of user-based turnover taxes that aim to tax the value

created by the ultimate users of digital services in a particular country.

is paper illustrates how digitalization has aected Asian economies and

their CIT and VAT systems, analyzing the impact of proposed reforms. It

builds on the IMF’s policy and analytical work in international taxation and

contributes to the policy debate by: (1) giving an overview of trends in digi-

1

A second pillar in these discussions deals with the introduction of an eective global minimum tax.

DIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIADIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIA

2

talization in Asia and how this diers from other regions (Chapter1);

(2) discussing the implications of multilateral and unilateral tax policy

reforms aimed at taxing the income of companies in an increasingly digi-

talized economy (Chapter2); and (3) exploring how best to address VAT

challenges in the face of expanding online sales (Chapter3). It is important

to note that the nexus of digitalization and tax go beyond what is discussed

in the paper, including issues of property rights over private information and

the use of technology in tax design and revenue administration.

Introduction

3

is chapter describes the landscape of digitalization in Asia. Digitalization is

having a profound impact on Asia’s economy, underpinned by widespread inter-

net access. Digitalization extends well beyond the large ICT sector, with high

levels of e-commerce and automated digital services. Asia stands out in its large,

highly digitalized and locally headquartered tech giants, operating alongside US

MNEs. e rapid growth of Asia’s homegrown tech giants and the presence of

US MNEs highlights the importance of appropriate tax policies for these highly

digitalized businesses.

Digitalized economic activity in Asia encompasses both the ICT sector and

other types of digitalized businesses.

For the purposes of this paper, the ICT sector is dened to include manufac-

turing of computers, electronic and optical products, publishing and broad-

casting, telecommunications and computer programming, and information

services.

1

Beyond the ICT sector, nearly all businesses in the formal economy

approach a “digital asymptote” (Figure1), using digital technology to varying

degrees, ranging from the use of digital systems to facilitate online order-

ing of goods to the provision of purely digital services (for example, online

gaming, search, and social media). is paper gives particular attention to

large, highly digitalized businesses, referred to as “tech giants.” ese tech

giants rely heavily on digital technology to carry on business, despite their

dierent business models, ranging from ICT manufacturers and retailers that

have built large e-commerce platforms, to online marketplaces that facilitate

e-commerce between third parties.

1

e ICT sector is measured using industry-level national accounts data and the relevant International

Standard Industrial Classication codes (G20 2018, United Nations 2008) for computer programming and

information services (Div. 62 63); telecommunications (Div. 61); publishing and broadcasting (Div. 58 60);

and manufacturing of computer, electronic, and optical products (Div. 26).

Digitalization in Asia

CCHAPTERHAPTER

1

5

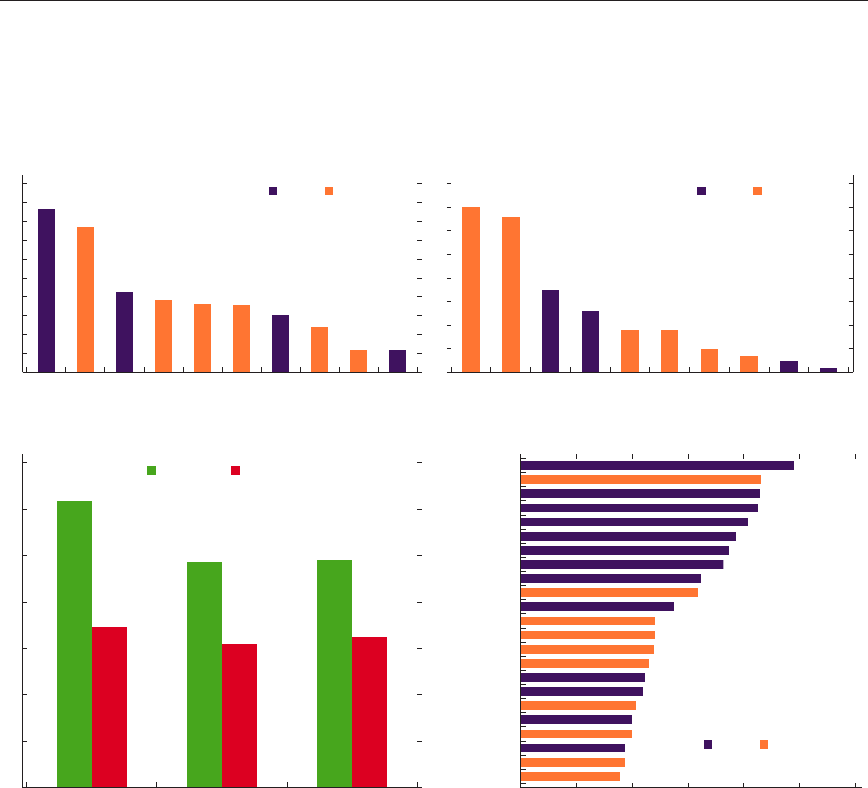

Asia’s ICT Sector

e ICT sector in Asia is among the world’s

largest. e sector accounts for more than

12, 7, and 6percent of total value added

in Korea, India, and Japan, respectively

(Figure2, panel 1), comparable in size to

most other OECD countries (IMF 2018a,

2018b).

2

China’s ICT sector is estimated

to be around 5.6percent of GDP (Herrero

and Xu 2018). e employment share of the

ICT sector in China’s urban areas is already

larger than in many OECD countries (Fig-

ure2, panel 2).

Asia’s ICT sector has grown rapidly, driven

by manufacturing, which has exhibited high

labor productivity. e strong growth of

the ICT sector’s real value added in Korea

and Japan is comparable to that of the United States and Europe (Figure2,

panel 3). China’s ICT sector is also estimated to have grown rapidly by about

10percent per year between 2013 and 2016 (Herrero and Xu 2018). Unlike

the United States and Europe, the ICT manufacturing sector in Korea has

recorded stronger growth than in ICT services and exhibited high labor

productivity (Figure2, panel 4), potentially reecting the region’s compara-

tive advantage in manufacturing relative to services. MNEs engaging in ICT

manufacturing may also provide digital services and engage in e-commerce

(for example, Apple, Samsung).

Digitalization Beyond the ICT Sector

Asia’s unrivalled level of internet connectivity, which has underpinned the

economy’s digitalization beyond the ICT sector, creates enormous scope for

future growth. Reecting their population size, China, India, and Indonesia

taken together have more than 2billion active mobile broadband connec-

tions, compared with approximately 500million in the United States (Fig-

ure3). Japan has more than 200million connections, while Bangladesh, the

Philippines, ailand, and Vietnam also each have 50–100million mobile

connections. e number of xed broadband connections is more than

three times as large in China as in the United States. Considerable potential

2

Although fully comparable data are not available, McKinsey Global Institute (2019) estimate that India’s

ICT sector accounted for around 7percent of GDP in 2017–18, mainly reecting IT and digital communi-

cations services.

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Note: ICT = information and communications technology.

Figure 1. A Digitalized Economy

E-commerce

(online sales, etc.)

Digital services;

online platforms

ICT sector

DIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIADIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIA

6

appears possible for further growth, particularly in China, Indonesia, and

South Asia, where the number of internet users as a share of the population

remains well below the level in the United States, as well as in other major

emerging market economies.

D26: Computer, electronic and optical products manufacturing

Total ICT sector

D58T60: Publishing, audiovisual and broadcasting activities

D61: Telecommunications

D62T63: IT and other information services

Non-ICT sector

Other ICT sector (incl. manufacturing)

IT and other information services

Non-ICT sector

Other ICT sector (incl. manufacturing)

IT and other information services

Computer, elect. and optical manufacturing

ICT sector

Publishing, audiovisual and broadcasting activities

Telecommunications

IT and other information services

Sources: OECD Structural Analysis Database (STAN, 2020 ed.); McKinsey Global Institute^; and Herrero and Xu (2018).^^

Note: In panel 1, ^2017–18 estimate, incl. IT & digital comms. services; electronics manufacturing. Breakdown unavailable.

^^2016 estimate, incl. electronic manufacturing, IT & telecommunications services. Breakdown unavailable.

^^^Europe incl. FRA, DEU, ITA and UK.

In panel 2, ^^estimate for 2010 in urban areas only. Breakdown unavailable.

**Data for computer, elect. and optical manufacturing only.

***Europe incl. FRA, DEU, ITA and UK.

In panel 3, *data for KOR are for 2005–2015 and sourced from the 2018 update of the STAN database.

**Data on the ICT sector in JPN include only ICT manufacturing.

***Advanced Europe incl. FRA, DEU, ITA and UK.

In panel 4, *data for KOR are for 2005–2015 and sourced from the 2018 update of the STAN database.

**Data on the ICT sector in JPN are missing except for ICT manufacturing.

***Advanced Europe incl. FRA, DEU, ITA and UK.

Figure 2. Asia’s ICT Sector

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

250

200

150

100

50

0

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

1. Value Added of ICT Sector

(Percent of total, 2017, or latest year available)

2. Employment in ICT Sector

(Percent of total, 2017, or latest available)

3. Real Value Added Growth of ICT Sector, 2005–2017

(In percent change)

4. Labor Productivity Growth of ICT Sector, 2005–2017

(In percent change)

160

140

120

100

60

80

40

20

0

KOR IND^ JPN CHN^^ AUS &

NZL average

USA Europe

average^^^

MEX KOR CHN^^ AUS & NZL

average

JPN** USA Europe

average***

KOR* JPN** USA Advanced

Europe***

MEX KOR* JPN** USA Advanced

Europe***

MEX

Digitalization in Asia

7

Online sales are more common in some Asian economies than in other

regions, including e-commerce exports. Business-to-consumer (B2C)

e-commerce in China and Korea is larger than in the United States, while

in Japan it is of similar size to other G7 economies (Figure4, panel 1).

Cross-border e-commerce is also substantial, with B2C e-commerce exports

in China and Japan exceeding those in some G7 economies (Figure4, panel

2). ese trends have continued during the pandemic. For instance, in 2020

alone, e-commerce sales grew by 30–50percent in Indonesia and Singapore,

some of the fastest growth rates even in comparison to other advanced econo-

mies (Figure4, panels 3 and 4).

Large and highly digitalized businesses—tech giants—thrive beyond the

ICT sector. Firms providing e-commerce and ntech services are closest to

the digital asymptote in ICT, nance, other professional services, wholesale,

and retail trade (Sedik 2018). Public companies from China (Alibaba, JD,

Meituan), Japan (Rakuten), and Singapore (Sea Limited) are among the

largest in Asia’s e-commerce space (Figure5) (Hvistendahl 2019, Ecommer-

ceDB 2019). Private companies including Korea’s Coupang and Indonesia’s

Go-Jek are also important players. ese local rms generate levels of reve-

nue in Asia similar to large US rms, including Amazon, Walmart, and their

local subsidiaries.

Asia

Non-Asia

Asia

Non-Asia

Source: International Telecommunications Union.

Figure 3. Internet Access in Asia

1600

1400

1200

0

1000

800

600

400

200

100

90

80

50

60

40

30

0

70

20

10

1. Active Mobile Broadband Connections

(2019, in millions)

2. Internet Users

(2019, in percent of population)

CHN IND IDN Other

Asia

Total

Europe

Total

North

America

Total

ZAF BRA CHN IDN IND BGD USA RUS TUR BRA MEX

DIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIADIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIA

8

How Is Digitalization in Asia Different?

Asia stands out from other regions in having home-grown tech giants that

rival US MNEs in size. China has several of the largest e-commerce com-

panies in the world, both measured in terms of market share or total sales.

For instance, China’s Alibaba Group and JD.com have about 38percent of

global e-commerce market share by merchandise volume (Figure6), although

the total value of Alibaba’s transactions is smaller than that of Amazon

(Box1). Alibaba operates China’s most-visited online marketplaces, Taobao

(consumer to consumer [C2C]) and TMall (business to consumer [B2C]),

while JD.com’s marketplace has a large in-house delivery network. Japan’s

Rakuten and Singapore’s Sea Group (trading as subsidiary Shopee) are other

major players in e-commerce. Asia is also home to some of the world’s largest

providers of digital services other than e-commerce, such as China’s Tencent

Non-Asia

Asia

Non-Asia

Asia

Non-Asia

Asia

Singapore

Indonesia

Sources: Statista; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development; and IMF staff calculations.

Figure 4. E-Commerce in Asia

10

9

8

7

6

4

3

5

2

1

0

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

1. E-Commerce Sales

(B2C, percent of GDP, 2017)

2. Cross-Border E-Commerce Sales

(B2C, percent of merchandise exports, 2017)

3. E-Commerce Sales

(Annual percentage change, 2017–20)

4. E-Commerce Sales

(Annual percentage change, 2020)

605030 40201002018 2019 2020

CHN UK KOR USA CAN FRA JPN DEU ITA IND

Germany

UK

Japan

USA

New Zealand

Russia

South Korea

Australia

Brazil

Italy

Spain

South Africa

China

Mexico

Singapore

Vietnam

Malaysia

India

Cambodia

Philippines

Thailand

Turkey

Indonesia

UK USA CHN JPN FRA CAN DEU ITA KOR NLD

Digitalization in Asia

9

(operating the WeChat communications, social media, and payment plat-

form) and Baidu (China’s largest internet search engine) (Figure7).

Unlike US MNEs, available evidence suggests that Asia’s homegrown tech

giants operate mainly within their domestic markets. While large US tech

giants generate the majority of their revenue outside the United States (Fig-

ure8, panel 1), major e-commerce providers such as Japan’s Rakuten derive

the bulk of their income from the Japanese market (Figure8, panel 2). is

also appears to be the case for China’s e-commerce giants. Expansion beyond

domestic markets is occurring, sometimes through joint ventures and acqui-

sitions of foreign rms. High prole examples include Alibaba’s purchase of

Singapore’s Lazard Group e-commerce rm, recent acquisitions by Singa-

pore’s Sea Group, facilitating expansion into ntech, as well as acquisitions in

recent years by Indonesia’s Gojek to expand its range of online products.

Asia’s homegrown tech giants appear to rely on intangible assets as much as

MNEs in the United States, and their protability is comparable. Firms that

derive value from intangible assets, such as intellectual property, can be more

dicult to tax since it is easier to shift these assets across borders to lower

tax jurisdictions. Intangible assets are also dicult to value for the purposes

of transfer pricing, whereby transactions within corporate groups, includ-

ing between subsidiaries and parent companies, are valued for tax purposes.

Using revenue per employee as a proxy for the degree of intangibility, it

appears that some of the Asian tech giants eclipse large US MNEs such as

Asian HQ

Non-Asian HQ

Source: Pitchbook Data Inc. Data have not been reviewed by PitchBook analysts.

*Japan only.

**Republic of Korea only.

90

50

60

80

70

0

20

10

40

30

JD

Alibaba

Amazon*

Meituan

VIPshop

Rakuten

Pinduoduo

Sea Limited

ebay**

Figure 5. Asian Sales of E-Commerce Companies (Public)

(Revenue, FY 2019, US$ billions)

Asian HQ

Non-Asian HQ

Sources: Statista; and Activate.

Figure 6. Global Market Share: E-Commerce

Companies (Public)

(Percent of total, by gross merchandise volume, 2019)

Alibaba

Amazon

JD

Pinduoduo

ebay

Other

Suning.com, Rakuten, Apple,

Walmart, Vip.com, and Sea Limited

DIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIADIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIA

10

Asian HQ

Non-Asian HQ

Asian HQ

Non-Asian HQ

Source: Pitchbook Data Inc. Data have not been reviewed by PitchBook analysts.

Figure 7. Turnover of Asia’s Tech Giants

300

250

200

0

150

100

50

180

160

140

80

100

60

40

0

120

20

1. Total Sales: E-Commerce Companies (Public)

(FY19, US$ billions)

2. Total Sales: Internet Companies (Public)

(FY19, US$ billions)

Amazon

JD

Alibaba

Meituan

VIPshop

Rakuten

ebay

Pinduoduo

Sea

Limited

Google Facebook Tencent Netflix Baidu Uber

Sales outside USADomestic sales in USA Sales in other countriesDomestic sales in country of HQ

Non-Asian HQ

Asian HQ

Non-Asian HQ

Asian HQ

Sources: Statista; and Pitchbook Data Inc. Data have not been reviewed by PitchBook analysts.

Note: MNEs = multinational enterprises.

In panel 1, *Sales in both USA and Canada.

In panel 2, *E-commerce sales only, 2019.

Figure 8. Sales, Productivity, and Profits of Asia’s Tech Giants

100

80

60

40

20

0

1.6

1.4

1.2

1.0

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0.0

100

80

60

40

20

0

1. Domestic vs Foreign Sales: US MNE’s (Public)

(Percent of total, FY19)

2. Domestic vs Foreign Sales: Asian Co’s (Public)

(Percent of total, FY19)

3. Labor Productivity of E-Commerce Co’s (Public)

(Revenue per employee, US$ millions, FY19)

4. Return on Equity: Internet & EComm. Companies (Public)

(Percent, average over FY17–FY19)

35

30

20

25

15

10

5

0

Pinduoduo ebay VIPshop Rakuten Alibaba JD Amazon

eBay Facebook Netflix* Uber Groupon Amazon

JD

VIPshop

Pinduoduo

Baidu

Meituan

Suning

Tencent

Alibaba*

Rakuten

Tencent

Facebook

Amazon

VIPshop

ebay

Alibaba

Google

Rakuten

Suning

Baidu

Digitalization in Asia

11

Amazon on this metric (Figure8) and are

broadly as protable, when judged by return

on equity in recent years.

Some of Asia’s largest home-grown tech

giants also appear to have income tax rates

comparable to those of US MNEs. Figure9

shows tax rates computed as income tax

expensed in a nancial year, as a percent of

pretax income, for a selection of large Asian

and US tech giants. Although this may not

capture tax paid precisely, it indicates that

tax outcomes for Asia’s tech giants can be

similar to large US digitalized companies.

e rapid growth of Asia’s homegrown tech

giants and the presence of US MNEs high-

lights the importance of appropriate tax pol-

icies for these highly digitalized businesses.

Asian e-commerce and internet giants Alib-

aba, JD, and Baidu have emerged as major players only in the last 10 years,

rivalling the turnover of Amazon, Google, and Facebook (Figure10, panel

1). Asian giants have also recorded solid growth in recent years (Figure10,

panel 2), comparable to large US MNEs. With continued expansion, revenue

collection from both local and foreign tech giants will become increasingly

important and appropriate tax policies will need to be in place to ensure that

revenue is distributed across countries in a manner that is perceived to be fair.

Asian HQ

Non-Asian HQ

Source: Pitchbook Data Inc. Data have not been reviewed by PitchBook analysts.

25

5

10

20

15

0

Suning

VIPshop

Rakuten

Facebook

Alibaba

Tencent

Amazon

Google

Pinduoduo

ebay

Figure 9. Income Tax Expensed

(Percent of pretax income, average during FY18–FY19)

DIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIADIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIA

12

Amazon

Alibaba

Google

Tencent

Facebook

Baidu

Asian HQ

Non-Asian HQ

Source: Pitchbook Data Inc. Data have not been reviewed by PitchBook analysts.

Figure 10. Growth of Asia’s Tech Giants

300

250

200

0

150

100

50

45

40

35

30

15

20

10

5

–5

0

25

1. Sales of Internet Companies (Public)

(FY10, FY15 and FY19, US$ billions)

2. Profit Growth: Internet Companies (Public)

(Percent, average during FY15–FY19)

FY19 FY15 FY10

JD

Facebook

Amazon

Alibaba

VIPshop

Suning

Google

Tencent

Rakuten

ebay

Baidu

Digitalization in Asia

13

Alibaba is a Chinese tech giant with websites that serve as platforms for other sellers,

while Amazon has become an integrated retailer. Beginning in the late 1990s, Amazon

and Alibaba both developed comprehensive e-commerce websites (Laubscher 2018, Xu

2016). Alibaba’s websites have traditionally been a platform for third party sellers, with-

out marketing Alibaba’s own products or providing delivery services (Box Table1.1).

Amazon invested in an extensive delivery network for its goods and services, as well

as selling its own products via its website. e two tech giants have converged more

recently in some business decisions, as Alibaba jointly founded Cainiao Network in

2013, as a platform for businesses oering delivery services. Both Amazon and Alibaba

have also recently acquired traditional retail outlets, in Whole Foods (Amazon) and

Hema Fresh (Alibaba).

Amazon has signicantly higher turnover and is more protable. Although Alibaba

facilitates a higher volume of merchandise trade, Amazon has signicantly higher rev-

enue and larger prots. is may reect Amazon’s diversication, as the share of Ama-

zon’s revenue contributed by online e-commerce has declined from 65percent to about

50percent between 2016 and 2019, as its cloud computing services (AWS) and other

businesses have grown rapidly. E-commerce continues to account for more than 80per-

cent of Alibaba’s revenue (PitchBook Data, Inc).

Alibaba is an intangible business with signicant potential to expand internationally

similar to Amazon. Alibaba has less than a quarter of Amazon’s employees, given the

absence of an integrated retail and delivery network. is reects a less tangible business

model with signicant scope to increase use of its online platforms by foreign buyers

Box Table 1.1. Comparison between an American and Asian Tech Giant

Amazon Alibaba

Founded 1995 1999

Subsidiaries Amazon.com (B2C).

AWS for cloud computing.

Wholefoods traditional retail.

TMall (B2C) and Taobao (C2C).

Cainiao Network: delivery co platform.

Hema Fresh traditional retail

Foreign operations Localized versions of Amazon.com

operate in 20 countries.

Alibaba.com (B2B)

Aliexpress (B2C)

Lazard for e-commerce in SE Asia.

Revenue FY19 US$ 280.5 billion US$ 56.1 billion

Foreign Revenue FY19 31% 10.1%

Gross Profit FY19 US$ 74.7 billion US$ 25.3 billion

ROE

(FY17-19 avge)

21.2% 18.1%

Profit growth (FY15-19 avge) 37.2 % 32.1 %

Employees (2019) 798,000 116,519

Income tax expense (% pretax income,

FY18-19 avge)

17.7% 13.8%

Source: PitchBook Data Inc. Data have not been reviewed by PitchBook analysts.

Box 1. Amazon and Alibaba—Comparison between an American and Asian Tech Giant

DIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIADIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIA

14

and sellers. Progress has been limited so far, with most revenue generated by its Chinese

websites, unlike Amazon’s websites in multiple countries.

Alibaba’s tax obligations appear to be similar to those of Amazon in recent years. Aliba-

ba’s income tax expense (percent of pretax income) was 17.7percent on average during

FY2018 and FY2019, compared to 13.8percent for Amazon. Although an imperfect

measure of income tax paid, these gures do not suggest that either company enjoys a

signicant tax advantage over the other.

Box 1. Amazon and Alibaba (continued)

15

Digitalization in Asia

is chapter focuses on the international tax challenges stemming from a highly

digitalized economy, rather than domestic tax challenges related to prot shifting.

Under the proposed multilateral solution by the OECD Inclusive Framework,

investment hubs, including those in Asia, would lose revenue, while those with

a large user base or high-income consumers will likely gain. Other multilateral

policy alternatives go farther, calling for a complete replacement of the existing

CIT regime. While highly digitalized businesses are not explicitly targeted by the

OECD proposals, they remain some of the most aected. In the interim, some

countries in the region have introduced a DST on the receipts of non-resident

rms from the sale of services to residents. ese taxes raise low levels of revenue,

suggesting that the choice to introduce a DST needs to be weighed against other

reform priorities.

Challenges of Taxing Digitalized Businesses in Asia

e existing approach to taxing highly digitalized businesses operating inter-

nationally has been perceived as unfair by governments and civil society

organizations. e view held by many governments is that their citizenry is

remotely contributing to the rents generated by digital service providers from

other countries. First, increasingly sophisticated technology has facilitated

a large surge in both business to business (B2B) and business to consumer

(B2C) remote cross-jurisdictional sales/exports, challenging the concept of a

permanent establishment (PE) which requires a physical presence to generate

taxing rights for income taxes. Second, many governments claim that infor-

mation collected by companies on the personal preferences and habits of the

customer or “user” as they consume digital services—which is then processed

and monetized through personalized advertising and product development—

is contributing signicantly to the prots of these companies, without ade-

quate compensation to the users. Highly digitalized businesses may also

Income Tax for Highly Digitalized Businesses

in Asia—Challenges and a Way Forward

CCHAPTERHAPTER

2

17

have relatively more intangible assets, which are harder to value and easier

to relocate (Beer and Loeprick 2015), enabling prot shifting under existing

transfer pricing rules.

e impact of international tax policy reforms in Asia could dier from other

regions, given the unique landscape of digitalized businesses. Reducing the

importance of physical presence in determining a company’s income tax lia-

bility could increase the ability of Asian countries to tax foreign MNEs oper-

ating in Asia with few tangible assets. However, the home countries of Asia’s

tech giants could also lose revenue if these rms have to pay more tax in

other countries where they are expanding. e consequences for revenue col-

lection could be non-trivial, given that home-grown tech giants are growing

rapidly and face similar implicit tax rates to US MNEs. Some Asian countries

are also turning to DSTs—withholding taxes or user-based turnover taxes on

digital activities—as a unilateral means of taxing tech giants and other highly

digitalized businesses. is paper rst discusses multilateral tax reform pro-

posals and implications for the region before turning to digital services taxes

in Asia, potential trade-os, and economic implications.

Multilateral Reform

e OECD-led IF has proposed multilateral reform as a solution for taxing

an increasingly digitalized economy. e rst pillar of the policy proposal

seeks to adapt the international corporate tax system to new digitized busi-

ness models, by reallocating part of residual prot to market (or “destina-

tion”) countries. It would establish new taxing rights without requiring a

physical presence (new “nexus”). is reects a fundamental shift from exist-

ing norms by going beyond the arm’s length principle and moving toward

formulary methods when reallocating prots to the new nexus, thereby

addressing some of the challenges in taxing digitalized businesses. Notably,

this new taxing right would be overlaid on top of the existing system of inter-

national taxation.

1

e following are key elements of Pillar 1:

• A new taxing right for market jurisdictions over a share of residual profit

calculated at a consolidated MNE group (or segment) level (“Amount

1

Some countries consider the DSTs discussed in the following section, merely as an interim solution

until international agreement is achieved. Indeed, countries such as Belgium, Czech Republic and Hungary

have delayed the implementation of their DSTs, anticipating agreement on a multilateral solution can be

reached by mid-2021.

DIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIADIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIA

18

A”). Specifically, a portion (perhaps 20percent)

2

of the “residual profit”—

earnings in excess of “routine profits”—of MNEs with group revenues

above EUR 750million (USD 850million), that are engaged in automated

digital services or consumer-facing business would be allocated to market

(or “destination”) countries. Routine profit equates broadly to profits that

would be earned by an entity undertaking that activity on an outsourced

basis. There are different ways of calculating routine profits, but for this

purpose it is likely to be defined as some percentage (perhaps 10percent)

of revenue from unrelated party sales; the residual is any profit above this.

3

• A (separate) fixed return for certain baseline marketing and distribution activi-

ties taking place physically in a market jurisdiction, in line with the existing

arm’s length principle (”Amount B”). This does not create a new taxing

right, rather it secures a taxing right that already exists. It presents a simpli-

fication of existing rules and may help effective implementation of taxing

rights, wherein rules to ensure a minimum return to activities are currently

not well enforced, such as in developing Asian countries.

• Processes to improve tax certainty aimed at dispute prevention and resolution.

e second pillar introduces minimum taxation of inbound and outbound

investment. Pillar 2 applies more broadly and does not have a special treat-

ment for digital businesses and is not covered in this paper. However, some

countries (including the US)

4

see Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 as a package, with

acceptance of Pillar 1 predicated on acceptance of Pillar 2. Notably, by plac-

ing a oor on the CIT rate, Pillar 2 is expected to raise more revenue than

Pillar 1. Broader revenue implications of Pillar 1 for Asia are discussed below

and extend beyond the digital economy.

Implications of Amount A for Asia

MNEs headquartered in the Asia-Pacic region generate a signicant share

of the global residual prot covered by “Amount A.” Table1 reports on the

share of residual prots by country of headquarter for MNE groups with

annual revenue larger than EUR 750million (USD 850million). e size

and distribution of residual prots are reported separately for all industries,

ICT industries, and online retailers. Although these classications do not

directly map to the denition of consumer-facing businesses and automated

2

e OECD-IF argues that not all the residual is generated by the market jurisdiction (for example, some

reects risk-taking by the MNE), hence only a portion of the residual prot is reallocated.

3

For economists, routine returns may resemble a normal return on investment and “residual” prots, resem-

ble rents (earnings in excess of the minimum required by the investor).

4

For instance, the Made in America Tax Plan would bring the international minimum tax provisions (GILTI

and BEAT) closer in line with the OECD-IF’s Pillar 2 proposal. e plan envisages a higher minimum tax rate

of 21percent compared to the OECD-IF.

Income Tax for Highly Digitalized Businesses in Asia—Challenges and a Way Forward

19

digital services, they are nonetheless indicative.

5

Assuming that routine prots

are 10percent of revenue (that is, a 10percent protability threshold), global

residual prot across all industries is USD 1.5trillion. MNEs headquartered

in the US account for the bulk of residual prots (33percent), but a sizeable

share (32percent) are earned by MNEs headquartered in Asia-Pacic, with

China, Hong Kong SAR, Korea, and Japan playing a prominent role. Nar-

rowing the scope to the ICT industry shrinks the size of residual prots but

maintains the importance of MNEs headquartered in Asia-Pacic.

e ICT sector is relatively protable compared with other industry sectors,

disproportionately contributing to residual prot. e ICT sector is one

of the most protable industries as measured by the return to total assets,

and its residual prot as a share of total prot also ranks high compared to

other sectors (Table2). Although the sector falls within the narrow scope of

“Amount A,” even without this ringfencing, the high level of protability

means that rms in the sector are more likely to be included in the tax base.

e sector accounts for about 16percent of the global residual prots, which

is similar to the level of the nancial and real estate sector, but with a con-

5

e denition of consumer-facing business is not yet nalized.

Table 1. Residual Profit by Headquarter Jurisdiction, 2017

All industries (2017) ICT industry (2017)

Country

Share of

Global RP

(%)

Mean

RP/EBT

(%) Country

Share of

Global RP

(%)

Mean

RP/EBT

(%)

United States 33.1 18.0 United States 53.3 24.4

China 12.1 13.1 Hong Kong SAR 7.6 29.6

United Kingdom 8.0 11.0 China 6.7 23.2

Hong Kong SAR 5.9 32.1 Japan 6.6 11.6

South Korea 4.0 8.7 India 3.2 43.2

Japan 3.9 5.1 Germany 2.3 20.9

France 3.5 9.5 Canada 2.0 35.3

Germany 2.9 7.5 Netherlands 1.4 9.6

Canada 2.1 17.7 Australia 1.2 26.9

Russia 2.0 25.1 Spain 1.2 16.1

Other Asia Pacific 5.9 14.5 Other Asia-Pacific 5.7 18.8

Rest of the World 16.7 12.9 Rest of the World 8.8 12.9

Total 1,457 USD billions Total 236 USD billions

Online Retailers (2017)

Country

Share of

Global RP

(%)

Mean

RP/EBT

(%)

United States 65.1 10.1

Japan 26.8 2.9

China 8.1 7.4

Total 1.45 USD billions

Sources: S&P Capital IQ and IMF staff estimates.

Note: EBT = earnings before tax; RP = residual profit.

DIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIADIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIA

20

siderably smaller number of companies. e average return on assets in the

sector is twice as large as in the nancial sector. e median rate of return

ratio indicates divergence of protability within the ICT group.

Under the current system of international taxation, residual prots across

all industries are reported mainly in large economies and investment hubs.

Figure11 shows the location of residual prot for MNEs headquartered in

25 economies (including Australia, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Singa-

pore, and the United States) for all sectors, not just highly digitalized rms.

6

Together, these MNEs account for 71percent of total global residual prot.

With a protability threshold based on revenue (that is, the current de-

nition of residual prot under Amount A), about 44percent of the resid-

ual prot from these MNEs are declared in China and the United States,

followed by the Netherlands, Canada, and Puerto Rico. Other Asia-Pacic

economies with a sizeable share of residual prot include Australia, Hong

Kong SAR, and Singapore. Regionally, Europe has the largest share of resid-

ual prot (35percent) followed by Asia Pacic (31percent) and the Amer-

icas (29percent).

7

e presence of investment hubs potentially reects the

extent of prot shifting that occurs under the current regime. at said, these

results should be interpreted with caution, as the prot measure available can

include income from equity investment in aliates (for example, dividends

from subsidiaries) that are not subject to tax in the home country under cur-

rent rules, and not subject to redistribution under Pillar 1.

6

However, as noted above using consolidated data, digital rms account for a sizeable share of residual prots,

with the ICT sector alone responsible for 16percent of total residual prots. Hence the analysis presented here

should be viewed as illustrative. Indeed, digital rms are deemed to have greater opportunities for prot shift-

ing, given the importance of intangibles in their production process

7

Although the share of residual prot is evenly shared across the three continents, aliates located in Asia

tend to be more protable than their counterparts in other regions, earning a return on tangible assets of

17percent. e median aliate in Europe earns a 15percent return, and those in the Americas and Mid-

dle East earn a return of 8.5percent. e lowest returns are observed in Africa, with a return on assets of

only 4percent.

Table 2. Residual Profit and Other Descriptive Statistics by Sector, 2017

Industry Sector

Number of

Companies

mean

EBT/Assets (%)

median

EBT/Assets (%)

mean

RP/EBT (%)

Share of Global

RP (%)

Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing 25 8.3 8.3 12.6 0.2

Construction 298 5.6 4.7 5.2 1.0

Finance, Insurance and Real Estate 899 4.6 3.1 17.9 16.3

Manufacturing 2694 8.3 6.7 12.4 42.8

Retail Trade 608 8.1 6.2 3.7 2.1

Services 719 8.0 6.2 15.0 14.0

Transportation, Communications and Utilities 1160 5.9 4.5 20.2 20.3

Wholesale Trade 697 6.2 4.5 2.8 2.6

ICT 501 8.3 6.3 19.4 16.2

Sources: S&P Capital; and IMF staff estimates.

*ICT has overlaps with other sectors, so the sum of the share of Global RP is not 100 percent.

Note: EBT = earnings before tax; RP = residual profit.

Income Tax for Highly Digitalized Businesses in Asia—Challenges and a Way Forward

21

e location of residual prots is sensitive to the precise method of calcula-

tion. Using a protability threshold based on returns to tangible assets (in

this case 10percent of their value), the United States emerges as the top loca-

tion for residual prots while China accounts for only 4percent of residual

prot. is reects the importance of tangible assets in the creation of prot

for China (for example, manufacturing) compared to the United States.

e global revenue eect of Amount A is small, increasing CIT revenue by

about 0.5percent (OECD 2020a), but implications for individual jurisdic-

tions can be signicant. e revenue increase is driven by the reallocation

from jurisdictions with low taxes toward jurisdictions with higher taxes.

However, only a proportion of the residual prot will be reallocated. Using

a protability threshold of 10percent of unrelated party sales and assuming

only 20percent is available for reallocation, then the pool of residual prots

to be reallocated is estimated to be relatively small at USD 98billion, limit-

ing the size of the revenue increase (OECD 2020). For individual jurisdic-

tions, the impact on tax revenues depends on their current share of residual

prot relative to their share of sales. e OECD estimates that low-income

countries would increase their CIT revenue by approximately 1percent

(or 0.02percent of GDP) and middle-income countries by 0.5percent

(0.02percent of GDP).

8

e revenue impact for high-income countries show

8

Results are presented in OECD (2020a) as the percentage change in CIT revenue. IMF sta converted this

change in CIT revenue into percentage points of GDP for ease of comparison with the other results pre-

sented in this paper.

Sales definition

Asset definition

Source: OECD country by country reports for 2016; and IMF staff estimates.

Figure 11. Top 20 Locations of Residual Profit

(Percent of total)

15

0

5

10

20

25

30

35

China

United States

Netherlands

Canada

Puerto Rico

Bermuda

Australia

Hong Kong

SAR

Singapore

Ireland

Sweden

British Virgin

Islands

Cayman

Islands

Bahamas,

The

India

Norway

United

Kingdom

Indonesia

Peru

Vietnam

DIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIADIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIA

22

greater variability, they could lose or gain a small amount of revenue. Invest-

ment hubs unequivocally lose revenue, by as much as 3.9percent of current

CIT revenue (0.2percent of GDP).

Under an expanded scope, which includes rms in all industries, investment

hubs and developing economies in the Asia Pacic region could lose revenue

(Figure12). Discussions surrounding the scope of Amount A are ongoing,

with a possibility that the scope would be based on a size threshold, rather

than type of business activity.

9

In this case, the estimates presented here could

be closer to the expected impact. e range reects assumptions regarding

9

e top 100 largest MNE groups by revenue have revenue greater than USD 67billion, with an average rev-

enue of USD 127billion, and an average residual of USD 1.7billion. e headquarters of these MNE groups

are dispersed equally across Asia, Europe, and the Americas. e average size, in terms of revenue, in each

region is similar, but the average MNE group headquartered in the Americas have more than twice the residual

prot (USD 3.4billion) of the average Asian MNE (USD 1.6billion). e average residual prot of European

is the lowest at USD 305million.

Sources: OECD Country by Country Reports for 2016; and IMF staff estimates.

Note: The range reflects assumptions regarding the profitability threshold (10 percent or 20 percent of unrelated party sales) and share of residual profit to be

reallocated (10 percent or 20 percent). Increasing (decreasing) the share of residual profit to be reallocated results in a proportional increase (decrease). Increasing

the threshold reduces the size of the potential pool of profits to be reallocated, but for some countries this results in an increase in the revenue gain. This is because

it is assumed that each jurisdiction’s ‘contribution’ to the pool to be reallocated is in proportion to the jurisdiction’s current share of residual profit. So, with a higher

profitability threshold, the residual profit becomes more concentrated in select countries.

Figure 12. Potential Revenue Effects of Pillar 1, Amount A

(Percent of GDP)

0.00 0.100.05–0.20 –0.05–0.10–0.15

Australia

Bangladesh

Bhutan

Brunei Darussalam

Cambodia

China

Fiji

Hong Kong SAR

India

Indonesia

Japan

Korea

Lao P.D.R.

Macao SAR

Malaysia

Maldives

Mongolia

Myanmar

Nepal

New Zealand

Papua New Guinea

Philippines

Samoa

Singapore

Solomon Islands

Sri Lanka

Thailand

Timor-Leste

Vietnam

Income Tax for Highly Digitalized Businesses in Asia—Challenges and a Way Forward

23

the protability threshold (10percent or 20percent of unrelated party sales)

and share of residual prot to be reallocated (10percent or 20percent). For

instance, with a 10percent protability threshold and with 20percent of

residual prots reallocated, Vietnam could lose about 0.11percent of GDP

in revenue, driven by the prot reallocation of Japanese MNEs. Whereas

with a higher protability threshold, revenue eects are minimal. Similarly,

emerging economies such as India, Indonesia, and Malaysia could lose about

0.01percent of GDP in revenue or have a modest revenue gain. In contrast,

high-income countries such as Australia, Japan, and Korea, as well as large

markets such as China, gain revenue under the range of assumptions consid-

ered here. Singapore and Hong Kong SAR could lose about 0.15percent of

GDP in revenue. It is unsurprising that revenue losses are projected in these

investment hubs since they currently account for a disproportionate share of

residual prot compared to their market share.

10

Distributional eects dier

with the current proposal where the relative size of the in-scope sectors devi-

ates from the relative size of all MNEs. Annex1 provides an overview of the

methodology used to develop these estimates.

Digital Services Taxes

e use of unilateral measures to tax digital services is linked to wider global

discussions on expanding market (or “source”) country taxing rights. In a

context wherein direct taxation of prots is dicult, digital services taxes––

analogous to royalties imposed on the extraction of resource-rich countries––

allow countries to share in the rents of highly digitalized businesses. Data,

often proclaimed as the oil of the 21st century, have been a key driver for

new economic activity in recent decades. Such an analogy can be expanded

to the tax realm—if data on a country’s citizens are viewed as a collective

national asset, then just as the rents from natural resource extraction are

taxed in the host country in which they are located, the same could be

argued for personal data (IMF 2019, Aslam and Shah 2020). And, just as in

the extractive industries (Cui 2018, 2019; IMF 2019), a royalty instrument

(a tax on turnover) can substitute when direct taxation of rents is dicult,

especially where hard-to-value intangibles play a large role or capacity is lim-

ited to monitor cost-based prot shifting. Current DSTs, including in Asia

(Table3) take on the avor of (highly targeted) user-based royalties (Aslam

and Shah 2020).

10

For these estimates, residual prot is dened as prot above 10percent of unrelated party sales. Only

20percent of this residual is reallocated based on the share of destination sales in each jurisdiction. e

estimates assume that this reallocation is “funded” by countries relinquishing the residual prot to which they

currently have taxing rights.

DIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIADIGITALIZATION AND TAXATION IN ASIA

24

DSTs essentially attempt to overcome the “PE problem,” whereby a lack of

physical presence precludes governments from staking a claim to corporate

prots on a source basis. Since bilateral tax treaties preclude countries from

unilaterally adjusting taxing rights, countries have started to look for alterna-

tives outside the purview of income taxation. e key measures employed can

be categorized as follows:

• Withholding taxes on payments to non-residents for digital services. These

are levies on payments to non-residents for digital services and are similar

in concept to existing withholding taxes on cross-border technical services

(for example, accounting, management, and subcontractor services). While

initially such taxes focused on B2B payments for online advertising, they

have since expanded in-scope to cover other digital services as well as some

B2C transactions (typically relying on financial institutions as withhold-

ing agents). These withholding tax obligations have been justified as an

Table 3. Digital Services Taxes in Asia

Country Status Date Name Rate (%) Scope Threshold

Payment

Obligation

India Implemented April

2020

EL 2 Revenues received by non-

residents for online provision

or facilitation of sales of goods

and services to the Indian

market, advertising targeted at

Indian users, and sale of data

collected from Indian users

Companies generating

India-based digital services

revenue > INR 20 million in

a financial year

Paid by non-

resident

e-commerce

operators.

India Implemented March

2016

EL 6 Revenues received by non-

residents for online advertising

services supplied to Indian

residents

Aggregate payments to

nonresident > INR 100,000

in a financial year

Charged and

withheld by

resident payors

Malaysia Implemented May

2019

WHT 6 All income from e-commerce

transactions deemed to be

derived in Malaysia

Companies generating

revenue from consumers in

Malaysia >500,000 RMB/

year

Paid by

nonresident

digital service

providers

Indonesia Primary Law

Enacted

March

2020

ETT Not

Specified

Revenue received by non-

residents from e-commerce

sales to Indonesian consumers,

when the digital PE cannot be

applied due to the provision of

a tax treaty

The digital PE conditions

will be met by exceeding

thresholds for (i) group

consolidated gross turnover;

(ii) sales in Indonesia; and

(iii) active digital media users

in Indonesia

Paid by

nonresident

digital service

providers

Vietnam Under

Discussion

January

2021

WHT Variable Revenues received by

non-resident e-commerce

businesses for the supply of

services to residents

Not specified Collected

and withheld

by financial

institutions

New

Zealand

Under

Discussion

June

2019

DST 3 New Zealand-source revenue

received by intermediation

platforms, social media

platforms, content sharing sites

and search engines

Businesses with a global

consolidated annual turnover

of at least €750m, and

annual revenues attributable

to New Zealand of at least

NZ$3.5m (USD 2.3m).

Paid by

nonresident

digital service

providers

Sources: KPMG (2021); Avalara; and IMF reports.

Note: DST = digital services tax; EL = equalization levy; ETT = electronic transaction tax; WH = withholding tax.

Income Tax for Highly Digitalized Businesses in Asia—Challenges and a Way Forward

25

attempt to equalize (income tax) treatment on non-residents vis-a-vis resi-

dent service providers in a world with increasing cross border remote sales.

Tax rates on payments in scope vary widely at relatively high levels of 5 to

15percent globally.

• User-based taxes: DSTs typically apply to both residents and non-resident

companies, but their high global turnover and domestic revenue threshold

means that they in effect target a few large foreign MNEs.

11

An increas-

ing number of countries globally are opting for broader user-based DSTs,

motivated by the desire to capture some of the value being generated by

their citizens for highly digitalized businesses. Such DSTs target revenue

generated through interaction with users in their jurisdiction from a range

of digital services (whether for a payment or through the provision of a

free service).

12

Such DSTs are levied on a gross basis at relatively low rates,

ranging from 1.5 to 7.5percent on revenues from the sale of the digital

services in scope.

• Digital Permanent Establishment: A number of countries have proceeded

with the expansion of domestic rules to establish a taxing right for virtual

permanent establishments. A taxable permanent establishment to which

income tax obligations apply is deemed to exist when an MNE’s activities

exceed a global turnover and local sales and user thresholds.

13

However,

few countries have clearly articulated rules for revenue attribution to such

virtual PEs, and many countries will be constrained in applying a revised

PE definition, due to existing tax treaties.

Several countries in the region (Table3) have begun to adopt measures

that target income from digital activities generated in their jurisdiction by

non-residents. Larger middle-income countries without home-grown tech

giants appear to have been first-movers in the region. Countries that are

home to tech MNEs, primarily China, Japan, and Korea, have, thus far,

shown little interest in enacting DSTs. DSTs implemented to date or under

consideration differ significantly in terms of design (rates, scope, threshold,

and nature of payment obligation). For instance, Indonesia introduced a rule

to establish a taxing right for virtual permanent establishments in 2020. A

user-based DST has been implemented in India, with the new Equalization

11

High global revenue thresholds result in common DSTs, eectively capturing mainly important US MNEs,

which has been argued to create de facto discrimination (see Hufbauer and Lu 2018, and USTR 2021). e

eective targeting of US MNEs by DSTs, however, is a consequence of their market dominance and may be

temporary (Avi Yonah 2020).

12

is type of tax is typied by the 2018 European Commission draft directive for the taxation of digital