Report to Congressional Requesters

United States General Accountin

g

Office

GA

O

June 2004

TREATY OF

GUADALUPE

HIDALGO

Findings and Possible

Options Regarding

Longstanding

Community Land

Grant Claims in New

Mexico

GAO-04-59

Page i GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Letter 1

Executive Summary 2

Purpose of This Report 2

Historical Background 3

Results in Brief and Principal Findings 6

Congress Directed Implementation of the Treaty of Guadalupe

Hidalgo’s Property Provisions in New Mexico through Two

Successive Procedures 6

Heirs Are Concerned That the United States Did Not Properly

Protect Land Grants during the Confirmation Process,

but the Process Complied with All U.S. Laws 8

Heirs and others Are Concerned that the United States Did

Not Protect Community Land Grants After the Confirmation

Process, but the United States Was Not Obligated to Protect

Non-Pueblo Indian Land Grants after Confirmation 11

Concluding Observations and Possible Congressional Options

in Response to Remaining Community Land Grant Concerns 12

Chapter 1 Introduction—Historical Background and the Current

Controversy 14

Overview 14

New Mexico during the Spanish Period, 1598-1821 15

New Mexico during the Mexican Period, 1821-1848 19

The United States’ Westward Expansion and Manifest Destiny 21

Texas Independence and Statehood and the Resulting Boundary

Disputes between the United States and México 24

The Mexican-American War 25

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) 27

The Gadsden Purchase Treaty (1853) 32

Organization of the New U.S. Territory and Procedures to Resolve

Land Grant Claims 33

Factors Contributing to Different Mexican and U.S. Systems of

Land Ownership 34

The California Commission Legislation (1851 Act) 35

The New Mexico Surveyor General Legislation (1854 Act) 41

The Court of Private Land Claims Legislation (1891 Act) 43

Land Grant Issues in New Mexico Today 44

Objectives, Scope, and Methodology of This Report 45

GAO’s First Report 46

GAO’s Second Report 48

Contents

Page ii GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Summary 51

Chapter 2 Congress Directed Implementation of the Treaty

of Guadalupe Hidalgo’s Property Provisions in

New Mexico through Two Successive Procedures

52

Overview 52

The Surveyor General of New Mexico Investigated Claims from

1854 to 1891 54

The Surveyor General Was Assigned Responsibility to

Investigate Land Claims in 1854 55

The Investigation and Recommendation Process Followed

by the Surveyor General 59

Early Criticism of the Land Grant Confirmation Process

under the Surveyor General 67

Congressional Confirmations Ended after Controversy

over the Size of Large-Acreage Grants (the Tameling Case) 70

The Surveyor General’s Investigation of Land Grant Claims

Became More Rigorous in 1885 74

Repeated Attempts to Reform the Land Grant Confirmation

Process Were Finally Successful 76

The Court of Private Land Claims Adjudicated Claims from 1891 to

1904 77

The CPLC Legislation Established Specific Requirements

for Land Grant Adjudication 78

The Scope of the CPLC’s Equity Authority Was Unclear 81

The Land Grant Confirmation Process As Implemented

by the CPLC 83

The Federal Government Awarded Small-Holding Claims

within Rejected Land Grants 91

The Percentage of Acreage Awarded during the Two Confirmation

Processes Is Substantially Higher Than Commonly Reported 92

Summary 96

Chapter 3 Heirs and Others Are Concerned That the United States

Did Not Protect Community Land Grants during the

Confirmation Process, but the Process Complied

with All U.S. Laws

97

Overview 97

Land Grant Heirs and Others Have Concerns about the Results of

the Confirmation Procedures for Community Land Grants 100

Acreage and Patenting Issues Regarding the 105 Confirmed

Page iii GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Community Land Grants 100

Issues Regarding the 49 Wholly Rejected Community Land

Grants 108

Studies Have Focused on Three Core Reasons for Rejected

Acreage 112

The Courts Restricted Seven Confirmed Grants to Their

Individual Allotments (the Sandoval Case) 113

The CPLC Rejected Grants Made by Unauthorized Officials

(the Cambuston and Vigil Cases) 118

The CPLC Rejected Grants That Relied on Copies Made by

Unauthorized Officials (the Hayes Case) 121

Land Grant Heirs and Others Have Additional Concerns about the

Fairness and Equity of the Confirmation Procedures Followed

for Evaluating Community Land Grant Claims 124

Perceived Fairness and Due Process Issues with the

Surveyor General Procedures 124

Perceived Equity Issues with the CPLC Process 140

Any Conflict between the Confirmation Statutes and the Treaty

Would Have to Be Resolved under International Law or by

Additional Congressional Action 141

Summary 144

Chapter 4 Heirs and Others Are Concerned That the United States

Did Not Protect Community Land Grants after the

Confirmation Process, but the United States Was Not

Obligated to Protect Non-Pueblo Indian Lands

Grants after Confirmation

146

Overview 146

Heirs Claim That the United States Had a Fiduciary Duty to Protect

Confirmed Land Grants 147

Heirs Transferred Some Community Lands to Private

Ownership 149

Private Arrangements with Attorneys Resulted in Loss of

Community Lands 150

Partitioning Suits Led to Breakup of Common Lands 151

Property Taxes and Subsequent Foreclosures Led to Loss

of Land Ownership 152

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Provided No Special Protections

for Community Land Grants After Confirmation 153

The U.S. Government Currently Has a Fiduciary Duty to Protect

Pueblo Indian Lands 156

Summary 160

Page iv GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Chapter 5 Concluding Observations and Possible Congressional

Options in Response to Remaining Community Land

Grant Concerns

161

Overview 161

Potential Considerations in Determining Whether Any Additional

Action May Be Appropriate 162

Possible Congressional Options for Response to Remaining

Concerns 164

Summary 170

Appendix I Confirmation of Land Grants under the Louisiana

Purchase and Florida Treaties 171

The Louisiana Purchase Treaty 173

The Florida Treaty 175

Appendix II Articles VIII, IX, and Deleted Article X of the

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo 177

Appendix III Excerpts from the Protocol of Querétaro 178

Appendix IV Excerpts from the Treaty Regarding the Gadsden

Purchase 179

Appendix V Excerpts from the 1851 Act to Confirm California

Land Grants 180

Appendix VI Excerpts from the 1854 Act Establishing the

Office of the Surveyor General of New Mexico 183

Page v GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Appendix VII Excerpts from the 1891 Act Establishing the

Court of Private Land Claims 184

Appendix VIII Organizations and Individuals Contacted for

GAO’s Reports 189

Appendix IX Instructions Issued by Interior to the Surveyor General

of New Mexico as Required by the 1854 Act 193

Appendix X Data on the 295 Spanish and Mexican Land Grants

in New Mexico 200

Appendix XI Results of Evaluations of Claims for Land Grants

in New Mexico 209

Appendix XII Current Land Ownership within Originally Claimed

Grant Boundaries 214

Appendix XIII Contacts and Staff Acknowledgements 221

Tables

Table 1: Establishment of Surveyors General for the

Southwestern United States 41

Table 2: Surveyors General of New Mexico, 1854-1925 42

Table 3: Spanish and Mexican Land Grants in New Mexico 48

Table 4: Overview of the Results of the Surveyor General Land

Grant Confirmation Process of Spanish and Mexican

Land Grants in New Mexico, 1854-1891 60

Page vi GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Table 5: Grants Recommended for Rejection in Original

Decisions by the Surveyor General of New Mexico,

1854-1891 62

Table 6: Statutes Confirming Spanish and Mexican Land Grants

in New Mexico, 1854-1891 65

Table 7: Time Line of Key Events for the Maxwell and Sangre de

Cristo Land Grants 72

Table 8: Mexican Land Grants Confirmed by Congress in Excess

of 11 Square Leagues per Person in New Mexico, 1854-

1891 73

Table 9: Results of Surveyor General Julian’s Supplemental

Reports, 1885-1889 75

Table 10: Spanish and Mexican Land Grants in New Mexico for

Which Claims Were Filed with the CPLC, 1891-1904 85

Table 11: Number of New Mexico Grants for Which Claims Were

Filed and Ultimately Decided on Their Merits by the

CPLC 87

Table 12: Number of Grants in New Mexico Confirmed or

Rejected by the CPLC, 1891-1904 88

Table 13: CPLC Decisions Reversed by the U.S. Supreme Court 89

Table 14: Acreage Awarded for Spanish and Mexican Community

and Individual Land Grants during the Surveyor General

and the CPLC Land Grant Confirmation Processes in

New Mexico with and without Adjustments

(Subtractions) by GAO 93

Table 15: Summary of Adjusted Acreage Claimed in the CPLC’s

1904 Report 94

Table 16: Percentage of Acreage Awarded for Community and

Individual Spanish and Mexican Land Grants in New

Mexico, As Adjusted by GAO 94

Table 17: Percentage of Spanish and Mexican Land Grants

Confirmed in New Mexico, with and without

Adjustments for Claims Not Pursued 96

Table 18: Results for the 105 Community Land Grants in New

Mexico Confirmed in Part or Whole 101

Table 19: Community Land Grants with Boundary Disputes

Adjudicated by the CPLC, 1891-1904 104

Table 20: Results for the 49 Wholly Rejected Community Land

Grants in New Mexico 108

Table 21: Community Land Grants That Claimants Failed to

Pursue and Possible Explanations for This Failure 109

Page vii GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Table 22: Community Land Grants Rejected for a Variety of Legal

Reasons Unrelated to Authority of Granting Official or

Grant-Copying Official 111

Table 23: Community Land Grants Restricted to Their Individual

Allotments 113

Table 24: Decisions by the CPLC for Seven Community Land

Grants That Were Ultimately Restricted to Their

Individual Allotments 115

Table 25: Community Land Grants Made during the Mexican

Period That Were Rejected by the CPLC Because the

Granting Official Lacked Authority to Make Land

Grants under Mexican Law 118

Table 26: Community Land Grants Adjudicated by CPLC That

Involved Disputes over Copies of Grant Documents 122

Table 27: Non-Indian Community Land Grants with Originally

Confirmed Acreage and Currently Held Acreage 148

Table 28: Payments to Settle Land Claims for Pueblo Grants in

New Mexico, as of October 2002 158

Table 29: Comparison of Acreage Confirmed to Spanish Land

Grants for the Pueblos with Their Current Acreage, as

of December 31, 2000 159

Table 30: Community Land Grants in New Mexico Confirmed in

Full 210

Table 31: Community Land Grants in New Mexico Confirmed in

Part 211

Table 32: Rejected Community Land Grants in New Mexico 212

Figures

Figure 1: San Felipe Pueblo, New Mexico, c. 1880 18

Figure 2: Town of Las Vegas, New Mexico, c.1890 20

Figure 3: Generalized Depiction of U.S. Expansion 23

Figure 4: U.S. Land Acquisitions from México, 1845-1853 25

Figure 5: Provisions of 1854 Act Regarding Spanish and Mexican

Claims 56

Figure 6: Statements by Surveyors General of New Mexico and

Commissioners of the General Land Office Regarding

the Surveyor General Land Grant Confirmation Process 69

Figure 7: The CPLC, 1891 84

Figure 8: Sandía Mountain Range behind the Pueblo of Sandía,

New Mexico, c.1880 103

Page viii GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Figure 9: Current Land Ownership Within the Original Claimed

Boundaries of the Cañón de Chama Land Grant 215

Figure 10: Current Land Ownership Within the Original Claimed

Boundaries of the San Miguel del Vado Land Grant 216

Figure 11: Current Land Ownership Within the Original Claimed

Boundaries of the Petaca Land Grant 217

Figure 12: Current Land Ownership within the Originally Claimed

Boundaries of the Cieneguilla Land Grant 218

Figure 13: Current Land Ownership within the Originally Claimed

Boundaries of the San Antonio del Río Colorado Land

Grant 219

Figure 14: Current Land Ownership within the Originally Claimed

Boundaries of the Gotera, Maragua, and Cañada de San

Francisco Land Grants 220

Abbreviations

BLM Bureau of Land Management

CPLC Court of Private Land Claims

SGR Surveyor General Report

Page ix GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. It may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further

permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or

other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to

reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

B-302565

June 4, 2004

The Honorable Jeff Bingaman

The Honorable Pete V. Domenici

United States Senate

The Honorable Tom Udall

United States House of Representatives

In response to your request, this report: (1) describes the confirmation

procedures by which the United States implemented the property

protection provisions of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo with

respect to community land grants located in New Mexico, and the results

produced by those procedures; (2) identifies and assesses concerns

regarding these procedures as they pertain to the government’s

confirmation of these grants from 1854 to 1904; (3) identifies and assesses

concerns regarding acreage transferred voluntarily or involuntarily after

the confirmation procedures were completed; and (4) identifies possible

options that Congress may wish to consider in response to remaining

community land grant concerns.

As arranged with your offices, this report is being issued in English and

Spanish versions (GAO-04-59 and GAO-04-60, respectively). We will

distribute copies in both languages in New Mexico and provide copies

upon request. We also plan to send copies to the other members of the

New Mexico delegation in the House of Representatives.

If you or your staffs have any questions about this report, please contact

me at (202) 512-5400. Key contributors to this report are listed in appendix

XIII.

Susan D. Sawtelle

Associate General Counsel

United States General Accounting Office

Washington, DC 20548

Executive Summary

Page 2 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Whether the United States has fulfilled its obligations under the 1848

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, with respect to property rights held by

traditional communities in New Mexico, has been a source of continuing

controversy for over a century. The controversy has created a sense of

distrust and bitterness among various communities and has led to

confrontations with federal, state, and local authorities. Under the Treaty,

which ended the Mexican-American War, the United States obtained vast

territories in what is now the U.S. Southwest, from California to New

Mexico. Much of this land was subject to pre-existing land grants to

individuals, groups, and communities made by Spain and México from the

17th to the mid-19th centuries, and the Treaty provided for U.S.

recognition and protection of the property rights created by these grants.

Today, land grant heirs and legal scholars contend that the United States

failed to fulfill its treaty obligations regarding community land grants

within New Mexico. This contention is based in part on a belief that the

percentage of community land-grant acreage recognized by the U.S.

government in New Mexico was significantly lower than the percentage

recognized in California, and a view that confirmation procedures

followed in New Mexico were unfair and inequitable compared with the

different procedures established for California. The effect of this alleged

failure to implement the treaty properly, heirs contend, is that the United

States either inappropriately acquired millions of acres of land for the

public domain or else confirmed acreage to the wrong parties. According

to some heirs, the resulting loss of land to grantees threatens the

economic stability of small Mexican-American farms and the farmers’ rural

lifestyle.

In September 2001, GAO issued its first report on these issues, entitled

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: Definition and List of Community Land

Grants in New Mexico (GAO-01-951, Sept. 10, 2001).

1

Using a broad

definition of “community land grant”—as any grant setting aside common

lands for the use of an entire community—GAO identified 154 community

land grants out of a total of 295 grants made by Spain and México for lands

within New Mexico. In this second and final report, GAO discusses how

the community land grants were addressed by the courts and other entities

and how Congress may wish to respond to continuing concerns about

them. Specifically, this report: (1) describes the confirmation procedures

1

GAO simultaneously issued the report in Spanish—U.S. General Accounting Office,

Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo: Definición y Lista de las Concesiones de Tierras

Comunitarias en Nuevo México, GAO-01-952 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2001).

Executive Summary

Purpose of This

Report

Executive Summary

Page 3 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

by which the United States implemented the property protection

provisions of the Treaty with respect to New Mexico community land

grants and the results produced by those procedures; (2) identifies and

assesses concerns regarding these procedures as they pertain to the

government’s confirmation of these grants from 1854 to 1904; (3) identifies

and assesses concerns regarding acreage transferred voluntarily or

involuntarily after the confirmation procedures were completed; and

(4) outlines possible options that Congress may wish to consider in

response to remaining community land grant concerns.

As detailed in detail in chapter 1 and appendix VIII of this report, we

conducted substantial research and analysis in the preparation of these

two reports. We also widely distributed an exposure draft of our first

report, in response to which we received over 200 oral and written

comments. We contacted and interviewed numerous land grant heirs,

scholars, researchers, historians, advocates, and organizations familiar

with implementation of the property protection provisions of the Treaty,

as well as New Mexico county and state government officials and U.S.

government officials from several agencies. We reviewed archival

documentation describing the procedures established and followed by the

Surveyor General of New Mexico and the Court of Private Land Claims,

and evaluated numerous studies, books, law review articles, treatises, and

other materials. We researched the legislation creating the Surveyor

General and the Department of the Interior’s subsequent instructions to

the Surveyor General, and the legislation creating the Court of Private

Land Claims. We obtained and examined all of the community land grant

adjudicative decisions and reports from the Surveyor General of New

Mexico, the Court of Private Land Claims, and the U.S. Supreme Court,

and we researched pertinent provisions of the U.S. Constitution and other

federal laws and federal court decisions. We conducted our review for this

second report from September 2001 through May 2004 in accordance with

generally accepted government auditing standards.

From the end of the 17th century to the mid-19th century, Spain, and later

México, made land grants to individuals, groups, and towns to promote

development in the frontier lands that today constitute the American

Southwest. In New Mexico, land grants were issued to fulfill several

purposes: encourage settlement, reward patrons of the Spanish

government, and create a buffer zone between Indian tribes and the more

populated regions of its northern frontier. Spain also issued land grants to

several indigenous Indian pueblo (village) cultures that had occupied the

areas long before Spanish settlers arrived. In 1821, after gaining its

Historical

Background

Executive Summary

Page 4 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

independence from Spain, México continued to adhere to the land policies

adopted by Spain. México’s governance of New Mexico lasted until 1846

and was riddled with instability and frequent political changes in

government leaders, organization, and laws.

As reflected in the literature and in popular terminology, there were two

types of Spanish and Mexican land grants made in New Mexico:

“community land grants” and “individual land grants.” Community land

grants were typically organized around a central plaza, whereby each

settler received an individual allotment for a household and a tract of land

to farm, and common land was set aside as part of the grant for use by the

entire community. Spanish and Mexican law usually authorized the local

governor to make such community land grants, and the size of each grant

was a matter within the governor’s discretion. Individual land grants, as its

name suggests, were made in the name of specific individuals and usually

were made by the governor as well.

Much of Spain’s settlement in the northernmost provinces of the American

continent occurred with little interference, but in time, England and

France made their presence on the continent known. While France

established only a few interior settlements to facilitate trade, England

established permanent colonies along the Atlantic Coast and increasingly

migrated westward. The United States formally acquired its independence

from England in the 1783 Treaty of Paris and, with the establishment of a

federal government in 1789, the U.S. steadily acquired more land and

expanded south to Florida and west to California. Treaties with Spain and

France, for Florida and the Louisiana Purchase, respectively, and with

numerous Indian tribes, propelled the U.S. acquisition of land and

westward expansion. In 1845, when Texas achieved statehood as the

nation’s 28th state, U.S. territorial interests, including a plan to expand

settlement to the Pacific Ocean, collided with México’s territorial

interests. The Mexican-American War broke out over the boundary

between Texas and México, bringing an end to a 9-year boundary dispute.

Eventually, U.S. troops occupied Santa Fe, New Mexico; proclaimed New

Mexico’s annexation; and established U.S. government control over the

territory. In 1847, U.S. troops occupied Mexico City and shortly thereafter,

México surrendered. The war officially ended with the 1848 ratification of

the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits and Settlement, commonly referred

to as the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo forever altered the political landscape of

the North American continent. Among the Treaty’s provisions were

México’s cession to the United States of vast territories extending from

Executive Summary

Page 5 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

California to New Mexico and an agreement by the United States to

recognize and protect property rights of Mexican citizens living in the

newly acquired areas. In order to implement the Treaty’s property

protection provisions in California, Congress enacted legislation (the 1851

Act) creating a commission to review and confirm grants, with appeals

authorized to federal district courts and the U.S. Supreme Court. In

determining whether to recognize and confirm a grant, the 1851 Act

directed the California Commission to apply Spanish and Mexican laws,

customs, and usages, as well as equity principles, the law of nations

(international law), the provisions of the Treaty, and decisions of the U.S.

Supreme Court. The 1851 Act also directed the Commission to apply a

presumption in favor of finding a community land grant where a city,

town, or village existed at the time the Treaty was signed. In New Mexico,

by contrast, Congress established two different and successive

mechanisms for recognizing and confirming Spanish and Mexican land

grants. First, in 1854, Congress established (in the 1854 Act) the Office of

the Surveyor General of New Mexico within the Department of the

Interior. The Surveyor General was charged with investigating Spanish and

Mexican land grant claims and submitting to Congress recommendations

on their acceptance or rejection. The Surveyor General was directed to

examine the claims by applying Spanish and Mexican laws, customs, and

usages, and to treat the prior existence of a city, town, or village as clear

evidence of a grant. Because of fraud and other difficulties with this

process as well as the process in California, Congress established a second

mechanism in 1891, the Court of Private Land Claims (CPLC), to resolve

new and remaining claims in New Mexico and certain other territories and

states (excluding California, where claims already had been resolved). The

criteria that Congress established for the CPLC in determining whether a

land grant should be confirmed were more stringent than those it had

established for both the Surveyor General of New Mexico and the

California Commission. The CPLC could confirm grants only where title

had been “lawfully and regularly derived” under the laws of Spain or

México.

A number of factors contributed to the background against which the New

Mexico community land grants were investigated and resolved under these

two processes. For the most part, New Mexico consisted of a sparsely

populated area of subsistence agricultural communities, and inhabitants

were unfamiliar with the English language, the U.S. legal system, and

American culture. The Mexican legal system, for example, had consisted

largely of Spanish and Mexican codes and laws that were often interpreted

according to local custom and usage, and more formal tribunals and

Executive Summary

Page 6 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

courts did not play the same important role in México as they did in the

United States in interpreting and deciding issues and cases.

U.S. land tenure and ownership patterns also differed from those then

existing in New Mexico. Then as now, the U.S. system viewed the earth’s

surface as an imaginary grid laid out on a piece of paper, and cartography

and surveying were used to identify physical features of a particular

parcel. The exact measurements of parcels were identified and located on

a map, land ownership was primarily in “fee simple,” and land titles were

recorded in local government offices. Taken as a whole, this system

facilitated the use of land as a commodity that could be bought and sold.

By contrast, the Mexican and Spanish systems were rooted in a rural,

community-based system of land holding prevalent in medieval Europe.

That system was not based on fee simple ownership; instead, land was

viewed more in its relationship to the community, although parcels could

be sold to individuals after the land had been used and inhabited for a

certain number of years. Land was used primarily to provide sustenance to

the local population, rather than as a commodity that could be exchanged

or sold in a competitive market. Land boundaries were defined with

reference to terrestrial landmarks or the adjoining property, and because

these markers were often difficult to locate, Spanish and Mexican land

records sometimes lacked the geographic precision of the U.S. system.

As noted above, over a 50-year period starting in 1854, Congress directed

implementation of the property protection provisions of the Treaty of

Guadalupe Hidalgo in New Mexico for community land grants through two

distinct and successive procedures. First, in the 1854 Act, Congress

established the Office of the Surveyor General of New Mexico within the

General Land Office of the Department of the Interior (Interior). The

Surveyor General was charged with investigating the land grant claims

and, through Interior, making recommendations to Congress for final

action. The 1854 Act directed the Surveyor General to base his conclusions

about the validity of land grant claims on the “laws, usages, and customs”

of Spain and México and on more detailed instructions to be issued by

Interior. These instructions, in turn, directed the Surveyor General to

recognize land grants “precisely as México would have done” and to

presume that the existence of a city, town, or village at the time of the

Treaty was clear evidence of a grant. The Surveyor General investigated

Results in Brief and

Principal Findings

Congress Directed

Implementation of the

Treaty of Guadalupe

Hidalgo’s Property

Provisions in New Mexico

through Two Successive

Procedures

Executive Summary

Page 7 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

claims under this process from 1854 to 1891, and Congress confirmed the

vast majority of grants recommended for confirmation before the Civil

War in the early 1860s. Congressional confirmation ceased during the war

and resumed thereafter in the mid-1860s, but stopped again in the early

1870s because of concern about allegations of fraud and corruption. These

concerns finally were addressed with the advent of a new Presidential

administration in 1885, which scrutinized the confirmation process and

appointed a new Surveyor General. The new Surveyor General

reconsidered and reversed some of his predecessor’s recommendations to

Congress, and a backlog of land grant claims developed.

After several attempts at reform, Congress ultimately revised the

confirmation process in 1891 with passage of the 1891 Act. The 1891 Act

established a new entity, the Court of Private Land Claims (CPLC), to

resolve both new and remaining claims for lands in New Mexico (and

certain other territories and states). In part to prevent the type of fraud

and corruption which had characterized some of the claims filed in New

Mexico and California, Congress directed the CPLC to apply stricter legal

criteria for approval of land grants than Congress had established for the

Surveyor General of New Mexico. Under the new criteria, the CPLC could

confirm only those grants that claimants could prove had been “lawfully

and regularly derived” under Spanish or Mexican law, and the presumption

that Interior had directed the Surveyor General to follow—to find in favor

of a grant based on the previous existence of a city, town, or village—was

eliminated. Either the claimant or the U.S. government could appeal the

CPLC’s decisions directly to the U.S. Supreme Court, which could review

claims de novo, that is, without giving a presumption of correctness to the

CPLC’s rulings. Like the CPLC, however, the Supreme Court was bound by

the same legal criteria in determining whether a grant should be

confirmed: title to the land must have been “lawfully and regularly

derived” under Spanish or Mexican law. The CPLC adjudicated land grant

claims from 1891 through 1904. Thus over the 50-year history of the two

successive statutory land grant confirmation processes in New Mexico, the

legal standards and procedures applied in determining whether a

community land grant should be confirmed became more rigorous.

In discussing the results of these two confirmation procedures in New

Mexico, land grant scholars often have reported that only 24 percent of the

acreage claimed in New Mexico was awarded, for both community and

individual grants, in contrast to the percentage of acreage awarded in

California of 73 percent. In our judgment, the percentage of claimed

acreage that was awarded for New Mexico grants was actually 55 percent,

because the acreage that can fairly be viewed as having been claimed is

Executive Summary

Page 8 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

considerably smaller than that cited by land grant scholars, with the result

that a larger proportion of acreage was actually awarded. For example,

scholars include as grant lands claimed in New Mexico acreage that was

located outside of New Mexico, acreage that was covered by claims that

were withdrawn or never pursued, and acreage that was “double-counted.”

We believe the acreage attributable to these factors should be excluded

from a fair assessment of the confirmation process results.

The claims that were filed and pursued for the 154 community land grants

located in present-day New Mexico during this 50-year period

encompassed 9.38 million acres of land. The majority of these land

grants—105 grants, or over 68 percent—were confirmed, and the majority

of acreage claimed under these confirmed grants—5.96 million acres, or

63.5 percent—were ultimately awarded, although a significant amount

(3.42 million acres, or 36.5 percent) were not awarded and became part of

the U.S. public domain available for settlement by the general population.

Some of the confirmed grants were awarded less acreage than claimed,

and grants that were wholly rejected were awarded no acreage at all. Land

grant heirs and scholars commonly refer to acreage that was not awarded

during the confirmation process as “lost” acreage, and thus it is said that

community land grants “lost” 3.42 million acres during the confirmation

process. The circumstances surrounding this perceived loss have been a

concern of land grant heirs for more than a century.

A number of land grant heirs, legal scholars, and other experts have

charged that activities under the two federal statutory New Mexico

community land grant confirmation procedures did not fulfill the United

States’ legal obligations under the Treaty’s property protection provisions.

With respect to grants that were confirmed, heirs and others have voiced

concern about whether the full amount of acreage that they believe should

have been awarded was in fact awarded, as well as whether the acreage

awarded was confirmed and patented to the rightful owners. With respect

to grants that were rejected, the heirs’ principal concern is that no acreage

was awarded at all. Published studies have identified three core reasons

for rejection of claims for New Mexico land grants, all involving decisions

by the CPLC or, on appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court: (1) that under the

Supreme Court’s decision in the United States v. Sandoval case, the

courts confirmed grants but restricted them to their so-called “individual

allotments,” that is, to acreage actually occupied by the claimants; (2) that

under the Supreme Court’s decisions in the United States v. Cambuston

and United States v. Vigil cases, the courts rejected grants because they

had been made by unauthorized officials; and (3) that under the Supreme

Heirs and Others Are

Concerned That the United

States Did Not Properly

Protect Land Grants during

the Confirmation Process,

but the Process Complied

with All U.S. Laws

Executive Summary

Page 9 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Court’s decision in the Hayes v. United States case, the courts rejected

grants because they were supported solely by copies of documents that

had been made by unauthorized officials. These three reasons resulted in

rejection of claims for approximately 1.3 million acres of land in 17

different grants. If Congress had established less stringent standards in the

1891 Act for the CPLC to apply in evaluating claims for the New Mexico

community land grants, such as those it established for the California

Commission under the 1851 Act or the Surveyor General of New Mexico

under the 1854 Act, these results might have been different. Congress had

discretion in how it implemented the Treaty provisions, however, so long

as it did so within constitutional and other U.S. legal limitations (which it

did, as discussed below). Thus the fact that Congress established different

standards for grant confirmation at different times did not indicate any

legal violation or shortcoming.

In addition to these concerns by heirs about how specific claims were

adjudicated, some heirs and legal scholars have contended that there were

two more general problems underlying the Surveyor General and CPLC

processes. First, with respect to the Surveyor General procedures, heirs

and scholars contend that they did not meet the “fairness” requirements of

due process of law under the U.S. Constitution. We found that the

procedures did, in fact, meet constitutional due process requirements, as

the courts at that time defined them and even under today’s standards. All

potential land grant claimants were provided with the requisite notice of

the establishment of the Office of the Surveyor General and the

requirement to submit claims for any land grant for which they sought

government (congressional) confirmation. Persons who filed claims with

the Surveyor General were then given the requisite opportunity to be

heard in defense of their claimed land grants. Even persons who disputed

claims that had been filed with the Surveyor General based on their

allegedly superior Spanish or Mexican title, but who did not themselves

file a claim, had opportunity to be heard, both during the Surveyor General

process and thereafter—including to the present day. Second, with respect

to the CPLC process, heirs and scholars assert that it did not appropriately

consider principles of equity, particularly in comparison with the Surveyor

General process, but instead applied standards that were overly technical

and “legal.” We found that the CPLC did apply more stringent standards in

deciding whether to approve community land grants than the Surveyor

General had, but that these differences were the result of differences in

the authority and mandates that Congress established for the two entities.

Under the 1854 Act, the Surveyor General was directed to look to the

“laws, usages, and customs of Spain and México” in recommending a grant

for Congress’ confirmation, while under the 1891 Act, the CPLC was

Executive Summary

Page 10 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

directed to confirm only those grants that had been “lawfully and regularly

derived” under the laws of Spain, México, or any of the Mexican states. As

the U.S. Supreme Court explained in the United States v. Sandoval case,

the CPLC—and the Supreme Court in reviewing the CPLC’s decisions—

was required as a matter of U.S. law to act within the boundaries that

Congress had established in deciding whether to confirm grants under the

1891 Act. Because the 1891 Act directed the CPLC to apply more stringent

standards than the 1854 Act had established for the Surveyor General, the

Court explained in Sandoval, claimants had to look to “the political

department” of the U.S. government—the Congress—to address any

remaining concerns about consideration of “equitable rights.” Whether the

1891 Act appropriately considered equitable rights was a policy judgment

for the Congress in 1891, and it remains so today.

Finally, some scholars and legal commentators have raised questions

about whether the statutory confirmation procedures that Congress

established for New Mexico grants fulfilled the United States’ obligations

under the Treaty and international law. They contend that the substantive

requirements of the statutes—the standards that Congress set for

determining when a grant would be confirmed—were inconsistent with

the terms of the Treaty and international law, and thus even if the United

States carried out the statutory requirements, these allegedly did not

satisfy all of the government’s obligations. Under established U.S. law,

however, as articulated by the U.S. Supreme Court in the Botiller v.

Dominguez case and other decisions, courts are required to comply with

the terms of federal statutes that implement a treaty such as the Treaty of

Guadalupe Hidalgo that is not self-executing. (A treaty is not self-

executing if it requires implementing legislation before becoming

effective.) If an implementing statute conflicts with the terms of the treaty,

this conflict can be addressed only as a matter of international law or by

enactment of additional legislation. In the case of the Treaty of Guadalupe

Hidalgo, the evidence indicates that the substantive requirements of the

implementing statutes were, in fact, carried out, through the Surveyor

General of New Mexico and the CPLC procedures. Thus any conflict

between the Treaty and the 1854 or 1891 Acts—which we do not suggest

exists—would have to be resolved today as a matter of international law

between the United States and México or by additional congressional

action. As agreed, we do not express an opinion on whether the United

States fulfilled its Treaty obligations as a matter of international law. By

contrast, any concerns about the specific procedures that Congress, the

Surveyor General, or the CPLC adopted cannot be addressed under the

Treaty or international law, but only under U.S. legal requirements such as

Executive Summary

Page 11 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

the Constitution’s procedural due process requirements, and as noted, we

conclude that these requirements were satisfied.

Notwithstanding the compliance of the two New Mexico confirmation

procedures with these statutory and constitutional requirements, we found

that the processes were inefficient and created hardships for many

grantees. For example, as the New Mexico Surveyors General themselves

reported during the first 20 years of their work, they lacked the legal,

language, and analytical skills and financial resources to review grant

claims in the most effective and efficient manner. Moreover, delays in

Surveyor General reviews and subsequent congressional confirmations

meant that some claims had to be presented multiple times to different

entities under different legal standards. The claims process also could be

burdensome after a grant was confirmed but before specific acreage was

awarded, because of the imprecision and cost of having the lands

surveyed—a cost that grantees had to bear for a number of years. For

policy or other reasons, therefore, Congress may wish to consider whether

some further action may be warranted to address remaining concerns.

Some land grant heirs and advocates of land grant reform have expressed

concern that the United States failed to ensure continued community

ownership of common lands after the lands were awarded during the

confirmation process. They contend that the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

imposed a duty on the United States to ensure that these lands were not

subsequently lost through other means, either voluntarily or involuntarily,

and that because the United States did not take such protective action, the

United States breached this alleged “fiduciary” duty. (A fiduciary duty is a

duty to act with the highest degree of loyalty and in the best interest of

another party.) Land grant acreage has been lost, for example, by heirs’

voluntary transfers of land to third parties, by contingency fee agreements

between heirs and their attorneys, by partitioning suits that have divided

up community land grants into individual parcels, and by tax foreclosures.

Some land grant heirs also contend that the Treaty specifically exempts

their confirmed grant lands from taxation. These issues have great

practical importance to claimants, because it appears that virtually all of

the 5.3 million acres in New Mexico that were confirmed to the 84 non-

Pueblo Indian community grants has since been lost by transfer from the

original community grantees to other entities. This means claimants have

lost substantially more acreage after the confirmation process—almost all

of the 5.3 million acres that they were awarded—than they believe they

lost during the confirmation process—the 3.4 million acres they believe

they should have been awarded but were not.

Heirs and Others Are

Concerned that the United

States Did Not Protect

Community Land Grants

after the Confirmation

Process, but the United

States Was Not Obligated

to Protect Non-Pueblo

Indian Land Grants after

Confirmation

Executive Summary

Page 12 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

We conclude that under established principles of federal, state, and local

law, the Treaty did not create a fiduciary relationship between the United

States and non-Pueblo community grantees in which the United States was

required to ensure the grantees’ continued ownership of confirmed lands,

nor did it exempt lands confirmed to these grantees from state or local

property requirements, including, but not limited to, tax liabilities. The

United States does have a fiduciary relationship with the Indian Pueblos in

New Mexico and it protects community lands that the Pueblos obtained

under Spanish land grants. But this relationship is the result of specific

legislation, bringing the Pueblos under the same general protections

afforded to other Indian tribes, rather than the result of obligations

created under the Treaty. Thus the U.S. did not violate any fiduciary duty

to non-Pueblo community grantees.

As detailed in this report, grantees and their heirs have expressed concern

for more than a century—particularly since the end of the New Mexico

land grant confirmation process in the early 1900s—that the United States

did not address community land grant claims in a fair and equitable

manner. As part of our report, we were asked to outline possible options

that Congress may wish to consider in response to remaining concerns.

The possible options we have identified are based in part on our

conclusion that there does not appear to be a specific legal basis for relief,

because the Treaty was implemented in compliance with all applicable

U.S. legal requirements. Nonetheless, Congress may determine that there

are compelling policy or other reasons for taking additional action. For

example, Congress may disagree with the Supreme Court’s Sandoval

decision and determine that it should be “legislatively overruled,”

addressing grants adversely affected by that decision or taking other

action. Congress, in its judgment, also may find that other aspects of the

New Mexico confirmation process, such as the inefficiency and hardship it

caused for many grantees, provide a sufficient basis to support further

steps on behalf of claimants. Based on all of these factors, we have

identified a range of five possible options that Congress may wish to

consider, ranging from taking no additional action at this time to making

payment to claimants’ heirs or other entities or transferring federal land to

communities. We do not express an opinion as to which, if any, of these

options might be preferable, and Congress may wish to consider additional

options beyond those offered here. The last four options are not

necessarily mutually exclusive and could be used in some combination.

The five possible options are:

Concluding Observations

and Possible

Congressional Options in

Response to Remaining

Community Land Grant

Concerns

Executive Summary

Page 13 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Option 1: Consider taking no additional action at this time because the

majority of community land grants were confirmed, the majority of

acreage claimed was awarded, and the confirmation processes were

conducted in accordance with U.S. law.

Option 2: Consider acknowledging that the land grant confirmation

process could have been more efficient and less burdensome and imposed

fewer hardships on claimants.

Option 3: Consider establishing a commission or other body to reexamine

specific community land grant claims that were rejected or not confirmed

for the full acreage claimed.

Option 4: Consider transferring federal land to communities that did not

receive all of the acreage originally claimed for their community land

grants.

Option 5: Consider making financial payments to claimants’ heirs or other

entities for the non-use of land originally claimed but not awarded.

As agreed, in the course of our discussions with land grant descendants in

New Mexico, we solicited their views on how they would prefer to have

their concerns addressed. Most indicated that they would prefer to have a

combination of the final two options—transfer of land and financial

payment.

Chapter 1: Introduction—Historical

Background and the Current Controversy

Page 14 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

From the late 1600s until 1846, Spain, and later México, made a total of 295

grants of land within what today are the boundaries of New Mexico. These

grants were made to individuals, groups, and towns in order to promote

development in the frontier lands that now constitute the American

Southwest. Of these 295 grants, 141 were made to individuals, and the

remaining 154 were made to communities, including 23 grants made by

Spain to indigenous Indian pueblos (villages) in recognition of the

communal lands that the Pueblo people had held and used long before the

Spanish settlers arrived. The principal difference between a community

land grant and an individual grant was that the common lands of a

community land grant were held in perpetuity and could not be sold. Both

types of land grants fulfilled several purposes: they encouraged settlement,

rewarded patrons of the Spanish government, and created a buffer zone

between Indian tribes and the more populated regions.

As Spain and later México encouraged settlement along the northern

frontier, England established colonies that began at the Atlantic Coast and

extended westward. The United States, after establishing a federal

government in 1789, steadily acquired land and promoted expansion south

to Florida, west to California, and north to Oregon. The relative ease with

which the United States acquired the Louisiana Purchase (by 1803 treaty

with France) and Florida territories (by 1819 treaty with Spain), among

other areas, propelled U.S. acquisition of land and westward expansion. In

1845, when Texas achieved statehood as the nation’s 28th state, U.S.

territorial interests, including plans to expand settlement to the Pacific

Ocean, collided with México’s territorial interests. The Mexican-American

War broke out shortly thereafter, over the location of the boundary

between Texas and México, culminating a 9-year dispute. Eventually, U.S.

troops occupied Santa Fe, proclaimed the annexation of New Mexico, and

established U.S. government control over the territory. In 1847, U.S. troops

occupied Mexico City, and México soon surrendered. The war officially

ended with the 1848 ratification of the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits,

and Settlement, commonly referred to as the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo forever altered the political landscape of

the North American continent. Among the Treaty’s provisions was

México’s cession to the United States, for $15 million, of vast territories in

the southwest from California to Texas. The United States also agreed

under the Treaty to recognize and protect Mexicans’ ownership of

property within the ceded territory and to admit Mexican citizens living in

the ceded territory as U.S. citizens if they wished.

Chapter 1: Introduction—Historical

Background and the Current Controversy

Overview

Chapter 1: Introduction—Historical

Background and the Current Controversy

Page 15 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Today, 300 years after the first Spanish land grants were made in New

Mexico and 150 years after the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo,

conflicts persist over New Mexico community land grants. Many heirs of

those who claimed to own community lands at the time the Treaty was

ratified assert that the United States did not fulfill its treaty obligations.

The effect of this alleged failure, heirs contend, is that the United States

either inappropriately acquired millions of acres of land for the public

domain or else confirmed acreage to the incorrect parties. To assist the

Congress in deciding whether any additional measures may be appropriate

in response to these continuing concerns, and if so, what measures

Congress may wish to consider, GAO was asked to study a number of

issues. The results of this study are set forth in our first report on these

issues in September 2001, and in this second and final report.

The arrival of Columbus on the North American continent in 1492 heralded

the beginning of a Spanish campaign of exploration, conquest, and

settlement. In 1513, Ponce de Leon led an expedition into Florida. Six

years later, Hernando Cortés conquered the Aztec empire in central

México. To help govern his rapidly expanding colonial empire, the King of

Spain established a Council of the Indies in 1524, creating the vice-royalty

of New Spain, and later the vice-royalties of Peru, Buenos Aires, and New

Granada, and appointed a viceroy to govern each region. The viceroy of

New Spain governed from the new capital city of Mexico City and

appointed a general commander to govern locally in each of the vice-

royalty’s 10 provinces, including New Mexico and California. Initially, the

laws governing the empire came from Spain’s Las Siete Partidas. A

revised compendium of laws—known as the Nueva Recopilación de Las

Leyes de España—replaced them in 1567, with another compendium

following in 1680—the Recopilación de las Leyes de los Reynos de las

Indias—and another in 1805—the Novissima Recopilación de las Leyes

de España.

Spanish exploration of New Mexico and the greater southwest began in

earnest with the 1540 expedition of Francisco Vasquez de Coronado,

whose search for gold and silver led to encounters with native tribes of the

region. Coronado encountered Indian tribes who lived in villages, or

pueblos (as referred to by the Spanish explorers), which had been

occupied for centuries. (The term pueblo was also used to refer to the

Indians living in these communities; these persons were referred to as

Pueblo Indians or Pueblos.) The pueblo settlements were long-established

communal villages that were sustained by an agrarian economy.

New Mexico during

the Spanish Period,

1598-1821

Chapter 1: Introduction—Historical

Background and the Current Controversy

Page 16 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Significant Spanish settlement in New Mexico began in 1598 with the

arrival of an expedition led by Juan De Oñate. Oñate came as New

Mexico’s first provincial governor, and his office assumed all civil and

military authority in New Mexico. The governor had authority to do all that

was necessary to assure the proper functioning of the provincial

government, including supervising the founding of settlements and

maintaining the official files of documents that later formed the archives

of Santa Fe. Historically, the files of colonial governors and those of the

cabildo (the provincial council) became the central repository for all

official documents, including the registration of land titles and

conveyances. In 1609, Santa Fe became the provincial capital.

From 1610 to 1680, many settlers and others, such as Franciscan

missionaries, migrated to New Mexico. The settlers came to farm and raise

livestock, and they established towns and small communities. The

missionaries came to convert the Indians living in the province, and they

founded missions to teach the Indians Christianity and the Spanish culture

and language. In an effort to encourage Spanish settlement and collect

tribute, Spain awarded an encomienda to deserving subjects. Under the

encomienda system, a Spanish settler obtained the right to collect an

annual tribute from each head of family. The encomendero was obligated

to defend the province, give religious instruction to the natives, and

collect tribute from them.

The encomienda system, which relied on the labor and conversion of the

Indians, bred deep resentment. The Pueblo people soon developed a

common hatred for the encomienda and the suppression of Pueblo

religious practices by missionaries. In 1680, the Pueblos revolted and

within 11 days, all Spaniards living in New Mexico had fled to the El Paso

area. The Spaniards finally returned to New Mexico in 1693, and found

that part of the official archives—which had served as the central

repository of land grant documentation, along with privately held

documents that had not been taken by the Spaniards in the evacuation of

Santa Fe—had been among the revolt’s casualties. As a result, a good part

of the official documentation regarding ownership of land within New

Mexico at that time was lost.

A decree of 1684 appointing Don Domingo Jironza Petriz de Cruzate as

Governor and Captain General of New Mexico specifically authorized the

issuance of land grants in New Mexico. As in other provinces, Governor

Cruzate was assisted by alcaldes mayores, or mayors, who served multiple

functions, including investigating new petitions for land grants and placing

Chapter 1: Introduction—Historical

Background and the Current Controversy

Page 17 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

grantees in possession. Alcaldes also served as justices of the peace,

probate judges, sheriffs, tax collectors, and captains of the militia.

From the late 1600s until 1821, Spain made land grants to individuals,

groups, towns, and pueblos. These grants served several purposes: to

encourage settlement and colonial industries, to reward patrons of the

Spanish government, and to create a buffer zone between hostile Indian

tribes and more populated regions. Grants that were awarded to towns

and other group settlements in New Mexico were modeled on similar

communities created in Spain. In Spain, the King typically granted lands

adjacent to small towns to the community, for common use by all town

residents. Each settler received, in addition to use of common lands,

private lots for a home and farming and stock raising. Although neither

Spanish law nor Spanish land grant documents used the term “community

land grant,” many grants referred to lands set aside for general communal

use or for specific communal purposes such as hunting, grazing, wood

gathering, and watering. As a result, scholars, the land grant literature, and

popular terminology have commonly used the phrase “community land

grants” to denote grants that set aside common lands for the use of the

entire community, and we have adopted this term for our reports. The

principal difference between a community land grant and an individual

grant was that the common lands of a community land grant were held in

perpetuity and could not be sold or otherwise alienated, while an

individual grant could be transferred. Spain also declared itself guardian of

the pueblo communities, issuing grants to these settlements in recognition

of their communal nature. The Pueblo of San Felipe, shown in figure 1, is

an example of a pueblo community that was awarded such a land grant.

Chapter 1: Introduction—Historical

Background and the Current Controversy

Page 18 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Figure 1: San Felipe Pueblo, New Mexico, c. 1880

The procedure for obtaining a grant of land from the New Mexico

provincial governor typically involved several steps. First, prospective

landowners submitted a written petition to the governor describing the

requested area and asserting that it was vacant. The governor then, usually

writing in the margin of the petition itself, directed the alcalde mayor with

jurisdiction over the land to develop a sketch map of the proposed grant

area, noting the distance from neighboring settlements or pueblos and

reporting on whether there were other parties making claims adverse to

the petition. Depending on the information provided by the petitioner and

the alcalde mayor, a title of possession would be prepared by the

governor and delivered by the alcalde mayor to the petitioner. The alcalde

mayor then submitted a second report of these proceedings, called “the

juridical act,” to document the delivery of possession. After 4 years of

continuous possession by the petitioner, the grant became final. The

petition, alcalde mayor reports, title of possession, and grant were then

assembled into a single official package called the expediente. The

expediente for a community land grant was rarely complete because many

Source: Photo

g

ra

p

h b

y

John K. Hillers, courtes

y

Museum of New Mexico, Ne

g

ative No. 16094.

Chapter 1: Introduction—Historical

Background and the Current Controversy

Page 19 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

claimants preferred to keep records in their private possession. In

addition, many original grant records were simply lost.

In 1821, México (including the province of New Mexico) secured its

independence from Spain with the signing of the Treaty of Cordova.

Augustine Iturbide was subsequently elected Emperor of México and a

national council was established, although a revolution ousted Iturbide

after a year. The first 25 years of Mexican sovereignty were riddled with

instability and frequent changes in political leaders, organization, and

laws. Only one Mexican president served a full term in office during this

period. The changes in governments generally brought with them changes

in laws; for example, each government typically repealed and nullified the

laws of its predecessors. Thus, although the Treaty of Cordova had initially

adopted existing Spanish law for the Mexican nation, the legal

requirements changed repeatedly.

This continually changing legal regime made it difficult to ascertain which

official was authorized to make land grants at any given time. A 1681

Spanish law had given such authority only to the provincial governor, but

in 1813, Spanish law extended grant-issuing authority to a provincial

diputación (legislative body). In 1823, the Mexican Colonization Law of

Iturbide authorized ayuntamientos (town councils) to grant lands, but

regulations issued in 1828 to implement an 1824 Mexican Colonization

Law returned all grant-making authority to the governor.

2

Later, the

Mexican government passed still more legislation concerning land grants.

The enactment of these various laws also created uncertainties about

whether earlier laws had been repealed. As the U.S. Supreme Court later

described this situation in Ely’s Administrator v. United States, 171 U.S.

220, 223 (1898):

Few cases presented to this court are more perplexing that those involving

Mexican grants. The changes in the governing power as well as in the form of

government were so frequent, there is so much indefiniteness and lack of

precision in the language of the statutes and ordinances, and the modes of

procedure were in so many respects different from those to which we are

accustomed, that it is quite difficult to determine whether an alleged grant was

made by officers who, at the time, were authorized to act for the government, and

2

The Mexican government also entered into agreements with empresarios, who contracted

to provide settlers with tracks of land.

New Mexico during

the Mexican Period,

1821-1848

Chapter 1: Introduction—Historical

Background and the Current Controversy

Page 20 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

was consummated according to the forms of procedure then recognized as

essential.

Meanwhile, in the early 1800s, pioneers from the United States had begun

arriving in New Mexico. In 1807, a U.S. expedition led by Lieutenant

Zebulon M. Pike was intercepted by Spanish troops, arrested, and escorted

south to Chihuahua, México. Pike and his men were released near San

Antonio, Texas. By the 1820s, commerce had developed along the Santa Fe

Trail, extending from Independence, Missouri, west to Santa Fe. In New

Mexico, officials issued land grants to individuals and communities in an

effort to accommodate the expanding population. For example, in 1835,

México issued a community grant to the Town of Las Vegas. (See figure 2.)

México identified the Governor of New Mexico as the political chief, and

the territorial diputación (later the asamblea departmental) served as the

governor’s collective principal advisor. Larger towns in New Mexico had

ayuntamientos. In 1837, the prefectura (jurisdiction) system, in which a

prefect administered a geographical area and reported directly to the

governor, subsumed the ayuntamientos system of administration. As of

1844, New Mexico had three prefecturas: Rio Arriba in the north, Santa Fe

in central New Mexico, and Rio Abajo in the south.

Figure 2: Town of Las Vegas, New Mexico, c.1890

Source: Photograph by F. E. Evans, courtesy Museum of New Mexico, Negative No. 50798.

Chapter 1: Introduction—Historical

Background and the Current Controversy

Page 21 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

All told, from the end of the 17th century to the mid-19th century, Spain

and México made a total of 295 land grants—141 grants to individuals and

154 grants to communities, including 23 grants to Indian pueblos. The

Indian pueblos and most of the land grants were located in northern New

Mexico. The community land grants usually contained sufficient land and

water resources to facilitate settlement and establish communities. The

pueblo grants allowed the settled Indian tribes to continue to sustain their

communities through agriculture and animal husbandry, both of which

required land. México continued to recognize the communal nature of

Pueblo settlements of land and considered the residents to be Mexican

citizens. Water being an important commodity in an otherwise arid

landscape, most pueblo communities had been founded along the Rio

Grande and its tributaries.

After the establishment of the U.S. government in 1789, the United States

steadily acquired land and promoted settlement and expansion south to

Florida and west to California. The relative ease with which the United

States acquired the Louisiana Purchase and Florida territories, among

other areas, helped to propel additional U.S. land acquisition, settlement,

and expansion farther west. In 1845, John L. O’Sullivan, editor of United

States Magazine and Democratic Review, coined the phrase “manifest

destiny” to describe what had become a national movement to promote

expansion and “civilize” persons encountered along the way. In the years

since, some land grant heirs have contended that this Manifest Destiny

ideology contributed to a form of racism and arrogance detrimental to

Mexicans living in the New Mexico territory. According to O’Sullivan, the

claim to new territory was:

by the right of [America’s] manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the

whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the

great experiment of liberty and federative self-government entrusted to us. It is a

right such as that of the tree to the space of air and earth suitable for the full

expansion of its principle and destiny of growth.

3

O’Sullivan called on Americans to resist any foreign power that attempted

to thwart “the fulfillment of our manifest destiny to overspread the

continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly

multiplying millions.” O’Sullivan further argued that such providential

3

Alan Brinkley, American History: A Survey (McGraw Hill College, 10th ed. 1999), p. 430.

The United States’

Westward Expansion

and Manifest Destiny

Chapter 1: Introduction—Historical

Background and the Current Controversy

Page 22 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

favor gave Americans the right to bring the benefits of democracy to what

he considered more backward peoples, meaning Mexicans and Indians,

and if necessary, to do so by force.

Americans initially set their sights on establishing just a two-ocean

boundary. By 1900, however, U.S. territorial expansion had spread beyond

North American borders to non-contiguous areas, such as Alaska, Hawaii,

the Philippines and Puerto Rico. While most U.S. citizens celebrated their

self-proclaimed manifest destiny, Indian tribes, Mexicans, and Europeans

with claims in the Western Hemisphere did not. For them, the

overwhelming public support for expansion could only be interpreted as a

promise of conflict. Historians have surmised that a growing concern

about the future of the U.S. economy might have been behind the manifest

destiny ideology. In that vein, economic uncertainties may have led

politicians to assert that a new direction was needed and that the nation’s

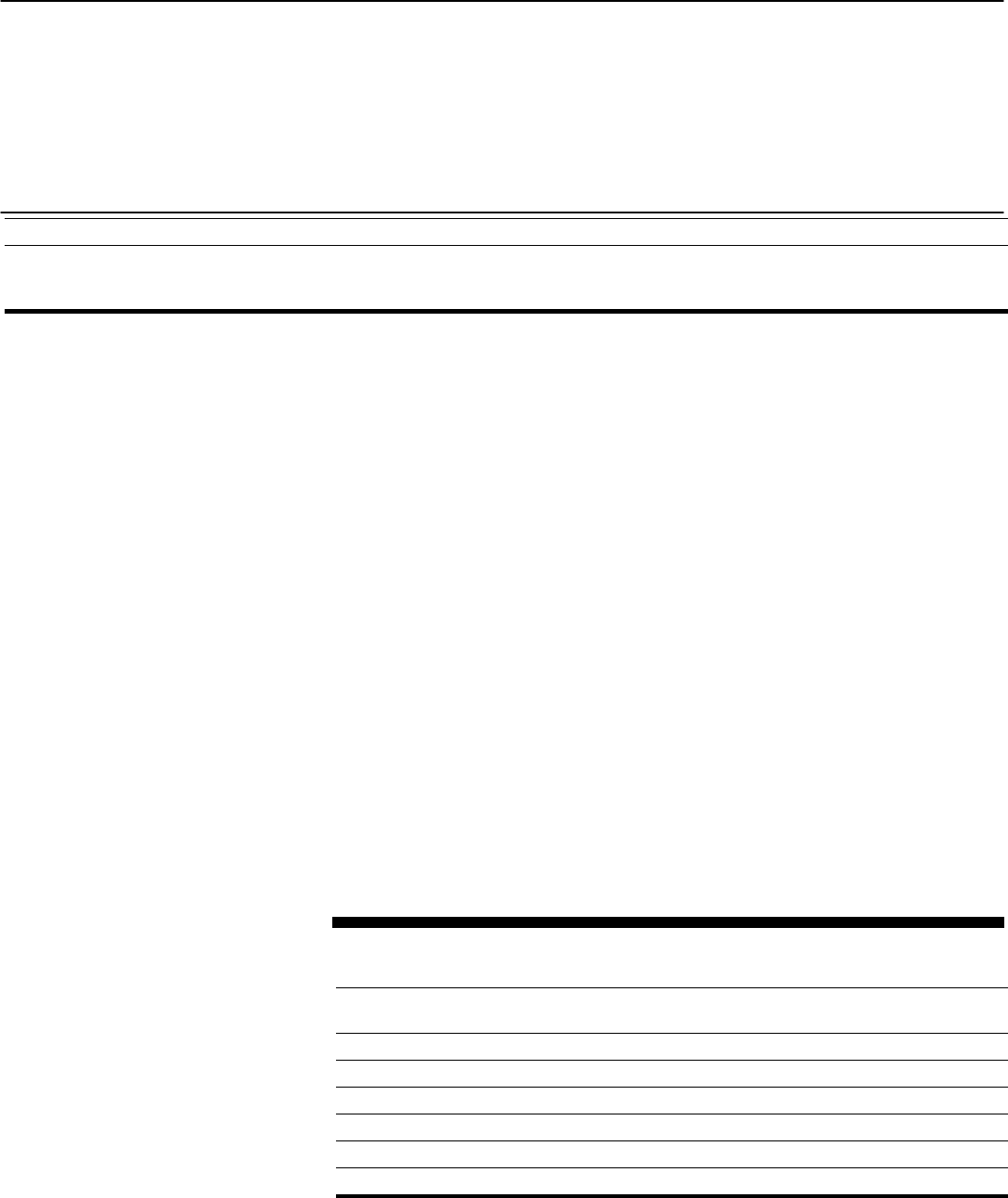

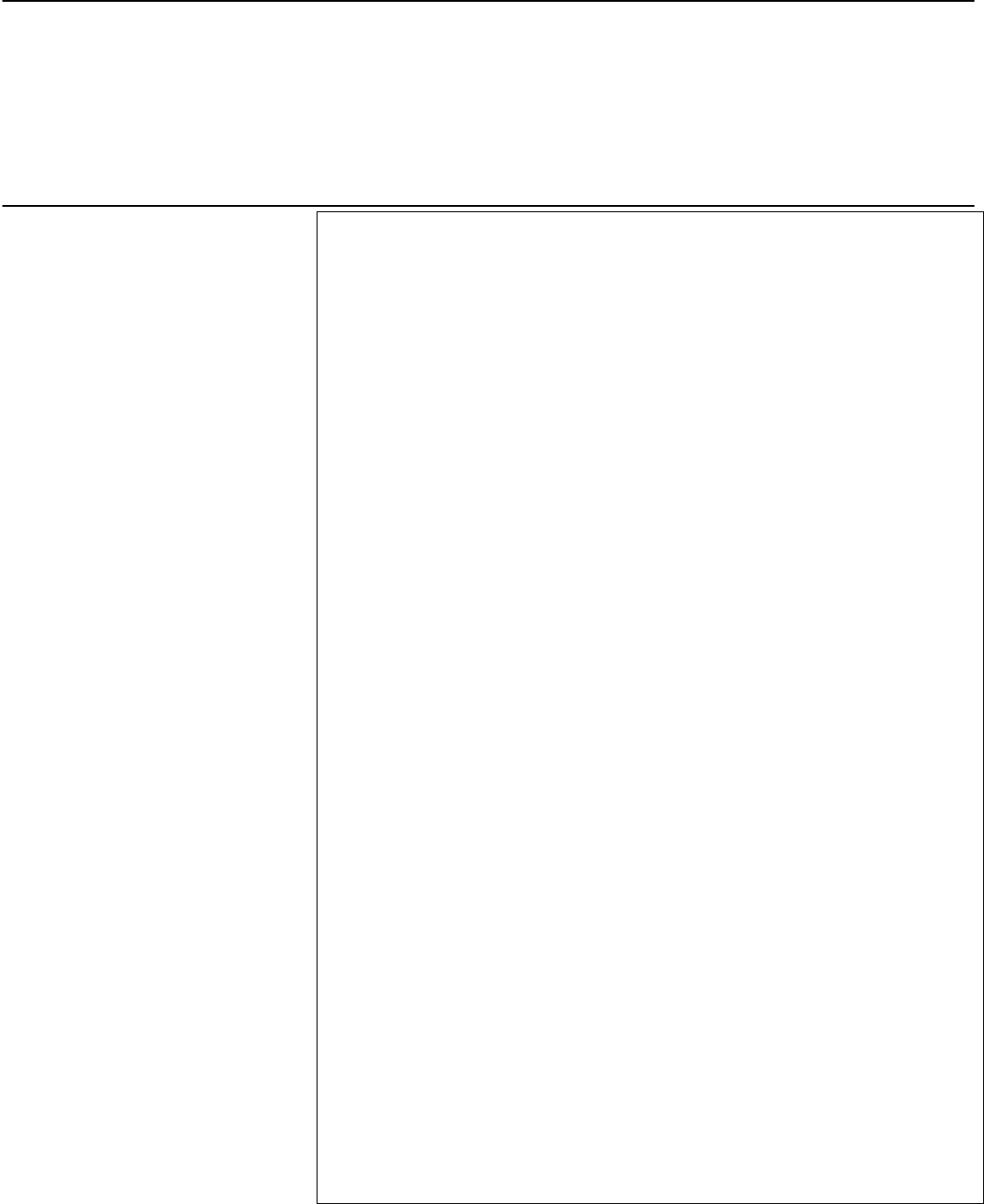

prosperity depended on a vast expansion of trade with Asia. Figure 3

depicts the expansion of the United States as it acquired land from France,

England, and Spain.

Chapter 1: Introduction—Historical

Background and the Current Controversy

Page 23 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Figure 3: Generalized Depiction of U.S. Expansion

Alaska Purchase, 1867

Hawaii

Annexed 1898

Gadsden Purchase, 1853

Treaty with Spain, 1819

British Cession, 1818

Disputed Area

Republic of Texas

Annexed 1845

Source: U.S. Geolo

g

ical Surve

y

.

Original 13 States and

their Territorial Claims, 1783

Louisiana Purchase, 1803

Mexican Cession, 1848

Oregon Compromise 1846

Chapter 1: Introduction—Historical

Background and the Current Controversy

Page 24 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Persistent disputes between the Mexican and U.S. governments over the

Texas boundary led to deterioration of the nations’ relationship. Spain had

laid claim to Texas in 1519 with the expedition of Alonso Alvarez de

Pineda, and in 1690, established it as a separate Spanish province with

undefined boundaries. When México gained its independence from Spain

in 1821, there were several Spanish settlements in Texas including Laredo,

Nacogdoches, La Bahia, and San Antonio. Meanwhile, in 1820, Moses

Austin, and later his son Stephen Austin, had petitioned Spain for

permission to found and promote a colony in Texas. Spain approved the

petition, and the colony proved to be successful and prosperous. In 1824,

México combined Texas and Coahuila as a new department and, under its

new colonization laws that offered liberal land grants, invited more

immigrants to Texas. The influx of immigrants increased the population of

Texas from 3,000 in 1821 to over 38,000 in 1836.

Concerned by the growth of an immigrant population, in 1830, México

barred further immigration from the United States. In 1835, Mexican

General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna established himself as dictator of

México. After México refused to grant Texans’ request for independence

and made efforts to reduce the size of the Texas militia, a convention of

Texas delegates declared independence from Mexican control. Santa Anna

responded with armed intervention. Texans suffered an initial defeat at the

Alamo, but won decisively at the battle of San Jacinto. In 1836, the

Republic of Texas claimed independence from México, and in 1845,

Congress passed a resolution inviting Texas to join the Union as a state.

On December 29, 1845, Texas became the 28th state. Figure 4 shows the

area claimed by both the Republic of Texas and México at the time Texas

became a state.

Texas Independence

and Statehood and the

Resulting Boundary

Disputes between the

United States and

México

Chapter 1: Introduction—Historical

Background and the Current Controversy

Page 25 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Figure 4: U.S. Land Acquisitions from México, 1845-1853

The beginnings of the Mexican-American War occurred on April 5, 1846,

when U.S. General Zachary Taylor was ordered to occupy the area in

dispute between Texas and México. President James K. Polk believed that

the disputed area belonged to the United States, and on May 13, 1846, he

declared that a state of war existed between the two countries. Brigadier

General Stephen Watts Kearny led the U.S. Army of the West out of Fort

Leavenworth, Kansas, for the conquest of New Mexico and California. In

August 1846, as General Kearny’s troops arrived in Santa Fe, the Acting

The Mexican-

American War

Source: U.S. Geological Survey.

Mexican Cession, 1848

Disputed area: Claimed by Republic of Texas 1836-45; claimed by U.S. 1845-48

Republic of Texas, 1836-45: annexed by U.S. 1845

Gadsden Purchase, 1853

CA

NV

AZ

NM

TX

OR

ID

UT

CO

KS

NE

WY

IA

IL

MO

MS

OK

AR

LA

Chapter 1: Introduction—Historical

Background and the Current Controversy

Page 26 GAO-04-59 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Governor of New Mexico, Juan Bautista Vigil y Alarid, officially

surrendered New Mexico to the United States.

In September 1846, General Kearny issued a collection of laws, known as

the “Kearny Code,” to govern the territory of New Mexico under military

rule. At the same time, General Kearny issued a “Bill of Rights,” modeled

closely on the protections contained in the U.S. Constitution. Based partly

on the laws of México, Texas, and Missouri, the Kearny Code provided for

the establishment of a government led by an appointed governor and

supported by a court system, which included the appointment of alcaldes

to resolve minor legal matters. The Kearny Code also established the

Office of Registrar of Lands to record all papers and documents in the new

territory “concerning lands and tenements” issued by the Spanish and