BRUCELLOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE:

EXPOSURES, TESTING, AND PREVENTION

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

CONTACT INFORMATION

Bacterial Special Pathogens Branch (BSPB)

Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology

National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

1600 Clifton Rd MS C–09, Atlanta, GA 30329-4027

(404) 639-1711, [email protected]

Division of Select Agents and Toxins (DSAT)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

1600 Clifton Rd MS A–46, Atlanta, GA 30329-4027

Fax: (404) 718-2096, [email protected]

http://www.selectagents.gov/

Emergency Operations Center (EOC)

Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(770) 488-7100

Laboratory Preparedness and Response Branch (LRN)

Division of Preparedness and Emerging Infection

National Center for Emerging, Zoonotic and Infectious Disease

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

1600 Clifton Rd MS C–18, Atlanta, GA 30329-4027

Updated February 2017

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contact Information ............................................................................................................ inside cover

Description ..........................................................................................................................................1

Clinical Description ..........................................................................................................................1

Case Classification

1, 2

........................................................................................................................ 1

Human Pathogens and Select Agent Reporting .................................................................................... 2

Select Agent Designation .................................................................................................................. 2

Laboratory Response Network (LRN)

6

.............................................................................................3

Reportable and Nationally Notifiable Disease Classification and Requirements

7

................................3

Case Report Form ............................................................................................................................ 4

Diagnostic Testing ...............................................................................................................................4

CDC/CSTE Laboratory Criteria for Diagnosis

1

................................................................................... 4

Testing performed at CDC ................................................................................................................5

Diagnostic Difficulties ......................................................................................................................6

Treatment

13, 14

......................................................................................................................................7

Laboratory, Surgical, and Clinical Exposures ........................................................................................8

Laboratory Exposures

4, 15

..................................................................................................................8

Clinical Exposure ........................................................................................................................... 12

Surgical Exposure

22, 23

..................................................................................................................... 12

Veterinary Exposures ......................................................................................................................... 14

Vaccine Exposure ........................................................................................................................... 14

Clinical Exposure ........................................................................................................................... 15

Marine Mammal Exposure

28, 29

........................................................................................................ 15

Foodborne Exposure ......................................................................................................................... 16

Recreational Exposure ....................................................................................................................... 17

Feral Swine Hunting ....................................................................................................................... 17

Brucellosis in Pregnant Women ......................................................................................................... 17

Person-to-Person Transmission ......................................................................................................... 18

Neonatal Brucellosis

36–40

................................................................................................................. 18

Sexual Transmission

41-48

.................................................................................................................. 19

Organ Donations and Blood Transfusions ....................................................................................... 19

Prevention ......................................................................................................................................... 19

Occupational Exposures ................................................................................................................. 19

Recreational Exposures (Hunter Safety) ..........................................................................................20

Travel to Endemic Areas ................................................................................................................. 20

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

References ......................................................................................................................................... 21

Additional Sources of Brucellosis Information: ...................................................................................24

Appendix 1: Specimen Submission .....................................................................................................26

Submission of Serum for Brucella Serology ....................................................................................... 26

Submission of Brucella Isolate(s) ...................................................................................................... 27

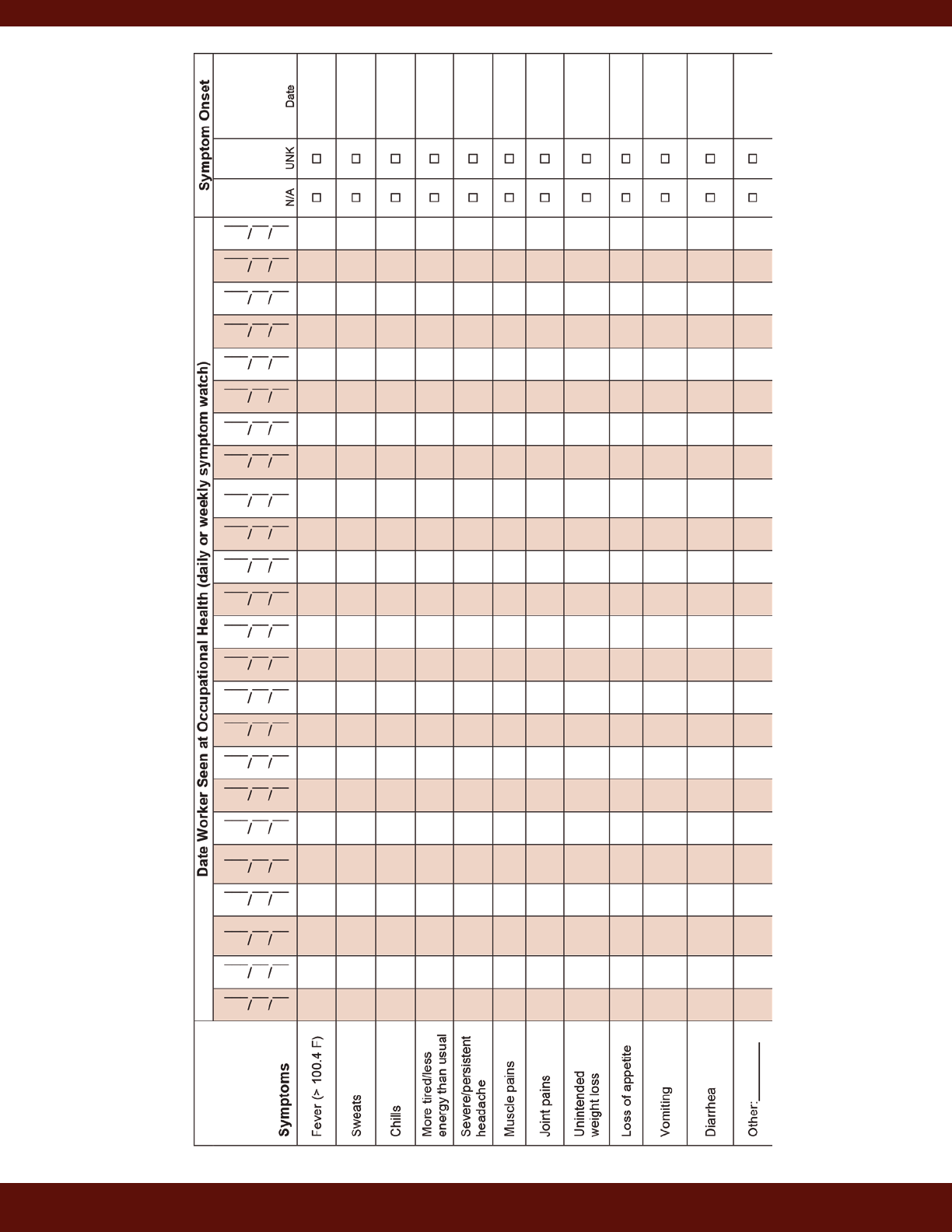

Appendix 2: Post-Exposure Monitoring .............................................................................................28

Follow-up of Brucella occupational exposure .................................................................................... 28

Symptom Monitoring ..................................................................................................................... 28

Appendix 3: Interim Marine Mammal Biosafety Guidelines ................................................................ 32

1

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

DESCRIPTION

Clinical Description

Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE)

1

2010 Case Definition

An illness characterized by acute or insidious onset of fever and one or more of the following: night sweats,

arthralgia, headache, fatigue, anorexia, myalgia, weight loss, arthritis/spondylitis, meningitis, or focal organ

involvement (endocarditis, orchitis/epididymitis, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly).

Incubation Period

●

Highly variable (5 days–6 months)

●

Average onset 2–4 weeks

Symptoms/Signs

●

Acute

Non-specific: Fever, chills, sweats, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, anorexia, fatigue, weight loss

Sub-clinical infections are common

Lymphadenopathy (10–20%), splenomegaly (20–30%)

Chronic

Recurrent fever

Arthritis and spondylitis

Possible focal organ involvement (as indicated in the case definition)

Case Classication

1, 2

Probable—A clinically compatible illness with at least one of the following:

●

Epidemiologically linked to a confirmed human or animal brucellosis case

●

Presumptive laboratory evidence, but without definitive laboratory evidence, of Brucella infection

Confirmed—A clinically compatible illness with definitive laboratory evidence of Brucella infection

Please refer to the CSTE Laboratory Criteria for Diagnosis section for specifications regarding “presumptive”

and “definitive” laboratory evidence of a Brucella infection.

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

2

HUMAN PATHOGENS AND SELECT AGENT REPORTING

Select Agent Designation

Select agents and toxins are a subset of biological agents and toxins that may pose a severe threat to public

health.

3

Brucella species are easily aerosolized and have a low infectious dose, cited at levels between 10 and

100 microorganisms. These organisms also have a prolonged incubation period with the potential to induce

a broad range of clinical manifestations, and therefore generate challenges for prompt diagnosis. The above

factors have contributed to a select agent designation for B. suis, B. melitensis, and B. abortus.

4, 5

Clinical or diagnostic laboratories and other entities that have identified B. suis, B. melitensis, or B. abortus

are required to immediately (within 24 hours) notify the Division of Select Agents and Toxins (DSAT) at CDC

(fax: 404-718-2096; email: [email protected]).

Facilities that use or transfer B. suis, B. melitensis, or B. abortus must immediately (within 24 hours) notify DSAT

via phone, fax, or e-mail if they detect any theft, loss, or release of these select agents. The initial report should

include as much information as possible about the incident, including the type of incident, date and time,

agent and quantity, and a summary of the events (location of the incident, number of individuals potentially

exposed, actions taken to respond, etc.). Additionally, appropriate local, state, or federal law enforcement

agencies should be contacted of a theft or loss, and appropriate local, state, and federal health agencies

notified of a release.

3

Forms for Reporting to CDC’s Division of Select Agents and Toxins (DSAT)

Form 4, Report of the Identification of a Select Agent or Toxin: Clinical or APHIS/CDC Form 4A should be

signed and submitted after a facility has identified B. suis, B. melitensis, or B. abortus contained in a clinical/

diagnostic specimen. Entities must submit Form 4 to DSAT within 7 calendar days of identification. For

assistance with the completion of this form, please contact CDC’s Division of Select Agents and Toxins via

email at [email protected].

Form 3, Report of Theft, Loss, or Release of Select Agents and Toxins: The APHIS/CDC Form 3 should be

submitted by facilities reporting a theft, loss, or release (laboratory exposure or release of an agent outside

of the primary barriers of the biocontainment area) of B. suis, B. melitensis, or B. abortus within 7 calendar days

of the event. For reporting of a theft or loss, complete sections 1 and 2 of Form 3; for reporting a release,

complete sections 1, 2, and 3. With questions regarding the Form 3, please send an e-mail to [email protected].

Exclusions from Select Agent Reporting

Select agents in their naturally occurring environment are not subject to regulation and may include animals

that are naturally infected with a select agent or toxin (e.g., milk samples that contain B. abortus). However, a

select agent or toxin that has been intentionally introduced (e.g., animal experimentally infected with B. suis,

B. melitensis, or B. abortus), or otherwise extracted from its natural source (e.g., blood from a culture bottle is

plated onto agar and grows B. suis) is subject to select agent regulation.

3

Attenuated vaccine strains of B. abortus Strain 19 live vaccine and B. abortus Strain RB51 are excluded from

select agent reporting requirements, unless there is any reintroduction of factor(s) associated with virulence.

3

Visit the Select Agents and Toxins Exclusions site for a comprehensive list of attenuated Brucella strain

exclusions. Please refer to the APHIS/CDC Form 5, Request for Exemption of Select Agents and Toxins for

an Investigational Product, to request an exemption from the select agent regulations.

3

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

Laboratory Response Network (LRN)

6

The LRN is a national network of local, state, federal, military, and international public health, food testing,

veterinary diagnostic, and environmental testing laboratories that provides laboratory infrastructure and

capacity to respond to biological and chemical public health emergencies.

Upon obtaining high confidence presumptive or confirmatory Brucella spp. results, LRN laboratories are

required to follow notification and messaging procedures.

Notification: Within 2 hours of obtaining high-confidence presumptive or confirmatory result, a LRN

Laboratory Director or a designee must notify:

●

their State Public Health Laboratory Director,

●

the State Epidemiologist,

●

the Health Officer for the State Public Health Department,

●

the CDC Emergency Operations Center (EOC), and

●

the FBI Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) POC.

Messaging: For emergency and non-emergency situations, LRN laboratories will submit data for all samples,

including positive and negative results related to the event within 12 hours of obtaining each result.

Please refer to Table 1 below for information regarding personnel who should be contacted, along with a

timeline for notification and messaging communication.

Reportable and Nationally Notiable Disease Classication and Requirements

7

Brucellosis is a reportable disease in all 57 states and territories; it is mandatory that disease cases be reported

to state and territorial jurisdictions when identified by a health provider, hospital, or laboratory. Reporting

requirements vary by jurisdiction.

Brucellosis is also a nationally notifiable condition. Notification of brucellosis cases (without direct personal

identifiers) to CDC by state and territorial jurisdictions is voluntary for nationwide aggregation and monitoring

of disease data. The case definition for confirmed and probable brucellosis can be found on page 3 under the

Case Classification section.

Immediate, Urgent Notification Status: For multiple confirmed and probable cases, temporally or spatially

clustered, notify EOC within 24 hours of a case meeting the notification criteria, followed by submission of

electronic case notification in the next regularly scheduled electronic transmission.

Standard: For confirmed and probable cases that are not temporally or spatially clustered, submit electronic

case notification within the next reporting cycle.

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

4

Table 1: Reporting Known Brucella spp. Human Pathogens

Brucella species

Select Agent

Designation

Reporting Notification Status

DSAT

LRN

Nationally

Notifiable

Condition

Identification

(Form 4)

Exposure

(Form 3)

Brucella melitensis

Select Agent

24 hours

For registered

entities

7 days

For

non-registered

entities

7 days 2 hours 24 hours or 7 days

Brucella suis 7 days 2 hours 24 hours or 7 days

Brucella abortus 7 days 2 hours 24 hours or 7 days

Brucella canis Not a Select Agent N/A N/A 2 hours 24 hours or 7 days

Brucella ceti, pinnipedialis Not a Select Agent N/A N/A 2 hours 24 hours or 7 days

Case Report Form

Health departments and providers are strongly encouraged to use the approved case report form to report

brucellosis cases to the Bacterial Special Pathogens Branch. This mechanism will ensure improved collection

of standardized data needed to assess risk factors and trends associated with brucellosis, so that targeted

preventive strategies can be implemented. Patient identifiers such as full name, address, phone number,

hospital name, and medical record number should not be included in forms sent to CDC. Instructions for

completion and submission are included in pages 1 and 2 of the form.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

CDC/CSTE Laboratory Criteria for Diagnosis

1

Definitive

●

Culture and identification of Brucella spp. from clinical specimens

●

Evidence of a four-fold or greater rise in Brucella antibody titer between acute and convalescent phase

serum specimens obtained greater than or equal to 2 weeks apart

Presumptive

●

Brucella total antibody titer of greater than or equal to 1:160 by standard tube agglutination test (SAT)

or Brucella microagglutination test (BMAT) in one or more serum specimens obtained after onset of

symptoms

●

Detection of Brucella DNA in a clinical specimen by PCR assay

NOTE: Evidence of Brucella antibodies by nonagglutination-based tests

DOES NOT meet the current CDC/CSTE case definition for a

Presumptive Diagnosis of brucellosis.

However, ANY quantitative test can be used for confirmation if

there is a four-fold or greater rise in Brucella antibody titer.

5

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

Testing Performed at CDC

The Zoonotic and Select Agent Laboratory (ZSAL) at CDC performs CLIA-approved Brucella spp. diagnostic

testing on human and animal samples.

Table 2: Diagnostic Testing Provided by ZSAL

Test

Samples

accepted

Pros Cons

Submission

Instructions

Culture

Tissue, whole

blood, sera,

plasma

Gold standard; allows

for genotyping-

molecular epidemiology

Requires BSL-3

See Appendix 1:

Submission of

Brucella Isolates

LRN PCR

(for suspect

BT and

response use)

Environmental

samples, swabs,

powders, whole

blood, sera, tissue

Rapid detection; can

be used on isolates and

clinical specimens

Requires technical expertise

to perform assay; reagents

and equipment can be

costly; optimal specimen

type not clear

See Appendix 1:

Submission of

Brucella Isolates

MAT

(serology)

Not available for

B. canis or RB51

Sera

Cheap, assay of

choice in acute non-

complicated cases; only

equipment needed is

reading apparatus

May not diagnose chronic

or complicated cases;

subjective

See Appendix 1:

Submission of Serum

for Brucella Serology

Results and Notification

●

BMAT results take 2 to 3 weeks, depending on when your sample was received at CDC’s Zoonotic and

Select Agent Laboratory (ZSAL), which is part of the Bacterial Special Pathogens Branch (BSPB). Our lab

will generally test your sample within 1 week; however, it can take longer to report results. Results will be

sent to your State Laboratory.

●

After checking with your State Laboratory, you can contact ZSAL or the BSPB epidemiology team if results

are not received within 2 to 3 weeks.

●

PCR results from primary specimens can be obtained within 24 hours.

Testing Performed Elsewhere

●

CDC does not provide medical consultation on individual patients, and cannot comment on results from

laboratory assays that we have not performed.

●

We recommend that you consult both with an infectious disease specialist assigned to the patient and the

medical director for the diagnostic laboratory that ran the tests for interpretation of results, as they have

the available parameters for the specific assay used.

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

6

Diagnostic Difculties

While culture is the gold standard, Brucella spp. can be fastidious, slow growers. Culture from primary

specimens may require up to 21 days of incubation. Bone marrow culture is more sensitive than blood;

however, the invasiveness of the procedure should be considered. Persons with chronic infections are less likely

to be culture-positive.

Agglutination is a confirmatory serological test to diagnose brucellosis. The standard tube agglutination test

(SAT) is the reference method, of which BMAT is a modified format.

●

Brucella-specific agglutination tests involve direct agglutination of bacterial antigens by specific antibodies.

Agglutination tests detect antibodies of IgM, IgG, and IgA classes.

●

IgM antibodies are predominant in acute infection but decline within weeks. Relapses are accompanied by

transient elevations of IgG and IgA antibodies but not IgM.

Stage of Brucellosis

nonagglutinating IgA

nonagglutinating IgG

IgG

IgM

Acute exacerbation

Acute

(up to 3 mo.)

IgM

IgG

IgA

Subacute

(3 mo. - 1 yr)

Chronic

(1 yr. onward)

Antibody

Levels

Positive

Blood

Cultures

Figure 1: Antibody Responses in Untreated Brucellosis.

8

IgM detection sensitivities using other EIA formats have been reported between 67% to 100% with limited

specificity data.

9, 10

Such tests are qualitative, making them difficult to interpret in a clinical setting, and might

have different performance characteristics and utility when used in areas with low disease prevalence, such as

the United States. Results of EIA tests must be confirmed by a quantitative reference method such as BMAT.

BMAT Testing Drawbacks

Cross-reactions and false-positive test results can occur in Brucella antibody tests, mainly with IgM.10

The primary immunodeterminant and virulence factor for Brucella species is smooth lipopolysaccharide (S-LPS)

on the outer cell membrane, which is antigenically similar to the lipopolysaccharide of other gram-negative

rods. False-positive Brucella test results can be caused by cross-reactivity of antibodies to Escherichia coli O157,

Francisella tularensis, Moraxella phenylpyruvica, Yersinia enterocolitica, certain Salmonella serotypes, and from persons

vaccinated against Vibrio cholerae.

BMAT tends to perform better for diagnosing acute cases rather than chronic cases.

11

Additionally, BMAT is

not as useful in detecting chronic brucellosis cases or neurobrucellosis. In a suspected chronic case, an IgG

ELISA would be more informative.

12

7

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

Treatment

13, 14

The table below provides a summary of the Red Book treatment recommendations, as well as several

recommended treatment documents. Information about post-exposure prophylaxis is provided below in the

section titled “Laboratory, Surgical, and Clinical Exposures.”

Table 3: Brucellosis Treatment Options

Subject Summary

Adults,

Children > 8 years

Combination therapy to decrease the incidence of relapse:

● Oral doxycycline (2–4 mg/kg per day, maximum 200 mg/day, in 2 divided doses) or oral

tetracycline (30–40 mg/kg per day, maximum 2 g/day, in 4 divided doses) -and-

● Rifampin (15–20 mg/kg per day, maximum 600–900 mg/day, in 1 or 2 divided doses).

● Recommended for a minimum of 6 weeks.

Combination therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ) can be used if

tetracyclines are contraindicated.

Children < 8 years

● Oral TMP-SMZ (trimethoprim, 10 mg/kg per day, maximum 480 mg/day; and sulfamethoxazole,

50 mg/kg per day, maximum 2.4 g/day) divided in 2 doses for 4 to 6 weeks.

Combination therapy: consider adding rifampin. Consult physician for dosing or if

rifampin is contraindicated. Tetracyclines (such as doxycycline) should be avoided in

children less than 8 years of age.

Pregnancy

Tetracyclines are contraindicated for pregnant patients. Consult obstetrician regarding

specific antimicrobial therapy instructions.

Complicated Cases

(endocarditis,

meningitis,

osteomyelitis, etc.)

● Streptomycin* or gentamicin for the first 14 days of therapy in addition to a

tetracycline for 6 weeks (or TMP-SMZ if tetracyclines are contraindicated).

● Rifampin can be used in combination with this regimen to decrease the rate of relapse.

● For life-threatening complications, such as meningitis or endocarditis, duration of

therapy often is extended for 4 to 6 months.

● Case-fatality rate is < 1%.

● Surgical intervention should be considered in patients with complications such as

deep tissue abscesses.

*May not be readily available in the U.S.

References

for Treatment

Recommendations

● Ariza J et al. 2007. Perspectives for the Treatment of Brucellosis in the 21st Century:

The Ioannina Recommendations. PLoS Med. 4(12): e317. http://www.plosmedicine.

org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040317

● Al-Tawfiq JA. 2008. Therapeutic options for human brucellosis. Expert Rev Anti Infect

Ther. 6(1): 109-120. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18251668

● Solera J. 2010. Update on brucellosis: therapeutic challenges. Intl J Antimicrob Agent.

36S, S18–S20. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20692127

Note: The B. abortus strain used in the RB51 vaccine was derived by selection in rifampin-enriched media and is resistant to rifampin in vitro.

This strain is also resistant to penicillin. If infection is due to this vaccine strain, treatment should be determined accordingly (example:

doxycycline and TMP/SMX in place of rifampin). Specifics on the regimen and dose should be established in consultation with the person’s

health care provider in case of contraindications to the aforementioned.

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

8

LABORATORY, SURGICAL, AND CLINICAL EXPOSURES

Laboratory Exposures

4, 15

Once a potential exposure is recognized, the first task is to determine the activities performed that may have

led to the exposure. Then identify:

1. who was in the laboratory during the suspected time(s) of exposure

2. where they were in relation to the exposure

3. what they did with the isolates

The identified individuals should be assessed for exposure risk using the descriptions in Table 4.

Table 4. Laboratory Risk Assessment and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP): Minimal (but not zero) Risk

Specimen

handling

Exposure scenario PEP Follow-up/monitoring

Routine clinical

specimen (e.g.,

blood, serum,

cerebrospinal

fluid)

Person who manipulates a routine

clinical specimen (e.g., blood, serum,

cerebrospinal fluid) in a certified Class

II biosafety cabinet, with appropriate

personal protective equipment (i.e.,

gloves, gown, eye protection).

None

N/A

May consider symptom watch for

following scenarios:

● Person who manipulates a routine

clinical specimen (e.g., blood,

serum, cerebrospinal fluid) on

an open bench with or without

appropriate personal protective

equipment (i.e., gloves, gown,

eye protection), or in a certified

Class II biosafety cabinet without

appropriate personal protective

equipment.

● Person present in the lab while

someone manipulates a routine

clinical specimen (e.g., blood,

serum, cerebrospinal fluid) on

an open bench, resulting in

occurrence of aerosol-generating

events (e.g., centrifuging without

sealed carriers, vortexing,

sonicating, spillage/splashes).

Person present in the lab while someone

manipulates a routine clinical specimen

(e.g., blood, serum, cerebrospinal fluid)

in a certified Class II biosafety cabinet,

or on an open bench where manipulation

did not involve occurrence of aerosol-

generating events (e.g., centrifuging

without sealed carriers, vortexing,

sonicating, spillage/splashes).

Enriched material

(e.g., a Brucella

isolate, positive

blood bottle)

or reproductive

clinical specimen

(e.g., amniotic

fluid, placental

products)

Person who manipulates enriched material

(e.g., a Brucella isolate, positive blood

bottle) or reproductive clinical specimen

(e.g., amniotic fluid, placental products)

in a certified Class II biosafety cabinet,

with appropriate personal protective

equipment (i.e., gloves, gown, eye

protection).

Person present in the lab while someone

manipulates enriched material (e.g., a

Brucella isolate, positive blood bottle)

or reproductive clinical specimen (e.g.,

amniotic fluid, placental products) in

a certified Class II biosafety cabinet.

9

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

Table 4. Laboratory Risk Assessment and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP): Low Risk

Specimen

handling

Exposure scenario PEP

Follow-up/

monitoring

Enriched material

(e.g., a Brucella

isolate, positive

blood bottle)

or reproductive

clinical specimen

(e.g., amniotic

fluid, placental

products)

Person present in the lab at a distance

of greater than 5 feet from someone

manipulating enriched material (e.g., a

Brucella isolate, positive blood bottle)

or reproductive clinical specimen (e.g.,

amniotic fluid, placental products),

on an open bench, with no occurrence

of aerosol-generating events (e.g.,

centrifuging without sealed carriers,

vortexing, sonicating, spillage/splashes).

May consider if

immunocompromised

or pregnant.

Discuss with health

care provider (HCP).

Note: RB51 is

resistant to rifampin

in vitro, and therefore

this drug should not

be used for PEP or

treatment courses.

Regular symptom

watch (e.g., weekly)

and daily self-fever

checks through

24 weeks post-

exposure, after last

known exposure.

Sequential

serological

monitoring at 0

(baseline), 6, 12, 18,

and 24 weeks post-

exposure, after last

known exposure.

Note: no serological

monitoring

currently available

for RB51 and B.

canis exposures in

humans.

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

10

Table 4. Laboratory Risk Assessment and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP): High Risk

Specimen

handling

Exposure scenario PEP

Follow-up/

monitoring

Roune clinical

specimen (e.g.,

blood, serum,

cerebrospinal

uid)

Person who manipulates a roune clinical

specimen (e.g., blood, serum, cerebrospinal

uid), resulng in contact with broken skin or

mucous membranes, regardless of working

in a cered Class II biosafety cabinet, with

or without appropriate personal protecve

equipment (i.e., gloves, gown, eye protecon).

Doxycycline 100mg

twice daily, and

rifampin 600 mg once

daily, for three weeks.

For paents with

contraindicaons

to doxycycline or

rifampin: TMP-

SMZ, in addion to

another appropriate

anmicrobial, should

be considered.

Two anmicrobials

eecve against

Brucella should be

given.

Pregnant women

should consult their

obstetrician.

Note: RB51 is resistant

to rifampin in vitro,

and therefore this

drug should not

be used for PEP or

treatment courses.

Regular symptom

watch (e.g.,

weekly) and

daily self-fever

checks through

24 weeks post-

exposure, aer

last known

exposure.

Sequenal

serological

monitoring at 0

(baseline), 6, 12,

18, and 24 weeks

post-exposure,

aer last known

exposure.

Note: no

serological

monitoring

currently

available for

RB51 and B. canis

exposures in

humans.

Enriched

material (e.g., a

Brucella isolate,

posive blood

bole) or

reproducve

clinical specimen

(e.g., amnioc

uid, placental

products)

Person who manipulates (or is ≤ 5 feet from

someone manipulang) enriched material

(e.g., a Brucella isolate, posive blood bole)

or reproducve clinical specimen (e.g.,

amnioc uid, placental products), outside of

a cered Class II biosafety cabinet.

Person who manipulates enriched material

(e.g., a Brucella isolate, posive blood bole)

or reproducve clinical specimen (e.g.,

amnioc uid, placental products), within a

cered Class II biosafety cabinet, without

appropriate personal protecve equipment

(i.e., gloves, gown, eye protecon).

All persons present during the occurrence of

aerosol-generang events (e.g., centrifuging

without sealed carriers, vortexing, sonicang,

spillage/splashes) with manipulaon of

enriched material (e.g., a Brucella isolate,

posive blood bole) or reproducve clinical

specimen (e.g., amnioc uid, placental

products) on an open bench.

Widespread aerosol generating procedures include, but are not limited to: centrifuging without sealed carriers,

vortexing, sonicating, or accidents resulting in spillage or splashes (i.e. breakage of tube containing specimen).

Other manipulations such as automated pipetting of a suspension containing the organism, grinding the

specimen, blending the specimen, shaking the specimen or procedures for suspension in liquid to produce

standard concentration for identification may require further investigation (i.e. inclusion of steps that could be

considered major aerosol generating activities).

Antimicrobial Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)

4, 15

Workers with high-risk exposures should begin antimicrobial post-exposure prophylaxis as soon as possible.

Prophylaxis can be initiated up to 24 weeks after exposure. PEP is generally not recommended for low-risk

exposures, though it may be considered on a case-by-case basis. PEP courses should include doxycycline

(100 mg) orally twice daily and rifampin (600 mg) once daily for a minimum of 21 days. Trimethoprim-

sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ) or another antimicrobial agent effective against Brucella should be selected (for

11

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

at least 21 days) if doxycycline or rifampin are contraindicated. All PEP regimen and dosing decisions should

be made in consultation with the worker’s health care provider. If clinical symptoms develop at any point while

on PEP and brucellosis infection is confirmed by culture and isolation or serology, PEP is no longer appropriate

and treatment and monitoring is required.

Persons who are pregnant, less than 8 years old, or have contraindications to these antimicrobial agents,

should consult with their health care provider for alternative PEP. Suitable combinations of agents may be

selected from the treatment references listed previously.

●

Exposure to B. abortus RB51: Upon exposure to rifampin-resistant B. abortus RB51 vaccine, PEP should be

comprised of doxycycline in addition to another suitable antimicrobial (such as TMP-SMX) for 21 days.

16

Specifics on the regimen and dose should be established in consultation with the person’s health care

provider in case of contraindications to the aforementioned.

Symptom Surveillance

4

An occupational health provider should arrange for regular (at least weekly) monitoring for febrile illness or

symptoms consistent with brucellosis for all exposed workers. In addition, daily self-administered temperature

checks are recommended for 24 weeks post-exposure, from the last known date of exposure. Exposed persons

should be informed of common brucellosis symptoms, and are encouraged to seek immediate medical

treatment if illness develops within 6 months of the exposure, regardless of whether or not the patient has

already undergone PEP. It is important for workers to notify their health care provider of their recent Brucella

exposure so that receiving diagnostic laboratories may be notified and take precautions. Individuals who have

risk factors for relapse of brucellosis

17

may require a follow-up time that extends beyond 24 weeks.

●

B. canis and B. abortus RB51: Symptom monitoring should be emphasized following exposures to

Brucella canis and Brucella abortus RB51 vaccine due to the lack of serological tests available to identify

seroconversion.

Specific information regarding common symptoms of brucellosis and a symptom-monitoring table are

available in Appendix 2. These tools can be distributed to occupational health staff.

Serological Monitoring

4

All exposed workers should undergo quantitative serological testing in order to detect an immune response to

Brucella spp. Evidence suggests that seroconversion can occur shortly before symptoms appear, and therefore

may be an earlier indicator of infection. It is recommended that sera be drawn and submitted to the same

laboratory at 0 (baseline), 6, 12, 18, and 24 weeks following the exposure event.

CDC’s Zoonotic and Select Agent Laboratory (ZSAL) is able to perform serial serological monitoring at no

cost. If monitoring is conducted by other laboratories, it is recommended that an agglutination assay is used

to quantify seroconversion. Instructions for serology submission to ZSAL are available in Appendix 1.

●

B. canis and B. abortus RB51: Serological testing is currently not available for Brucella canis and Brucella

abortus RB51 vaccine. Serological monitoring following exposure to these strains is not recommended,

except to collect a baseline serum sample in order to rule out infection with other Brucella spp.

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

12

Clinical Exposure

Universal precautions and personal

protective equipment (PPE) are essential

when working with body fluids or tissues

from a brucellosis patient. When standard

precautions are followed, most clinical

procedures are considered to be low-risk

activities. Higher-risk activities may include

handling of tissues with potentially high

concentrations of Brucella organisms (e.g.,

placental tissues), direct contact with

infected blood and body fluids through

breaks in the skin, or mucosal

exposure to aerosolized Brucella organisms

after an aerosol-generating procedure.

Aerosol-Generating Procedures: Aerosols

are defined as particulates (diameter < 10

µm) suspended in the air. Aerosol-generating

procedures are those that produce aerosols

as a result of mechanical disturbance of the blood or another body fluid

18

. Aerosol-generating procedures may

include, but are not limited to, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, disturbance of fluids from an abscess, the use

of saws or other electrical devices, and high-pressure irrigation. Additional information on the utilization of

electrical and irrigation devices can be found in the Surgical Exposure section below.

To the best of our knowledge, seven cases of occupationally acquired brucellosis have been reported in

the English literature among health care workers since 1990, including four infections acquired during

obstetrical delivery, and three infections through the provision of medical care to brucellosis patients. In

each case, it is likely that the health care workers were exposed through the high-risk routes of transmission

previously listed (handling of placental tissues, direct contact with infected blood/tissues, and mucosal

exposure to aerosolized Brucella).

19-21

Surgical Exposure

22, 23

In the event of a Brucella exposure during a surgical procedure, the potential risk of exposure should be

evaluated for all personnel who pass through the surgical unit. Assessments should be based on adherence

to PPE requirements, types of surgical devices utilized, risk of aerosolization, and duration of the surgical

procedure. The following paragraph, along with Table 5, may be used as a resource for risk assessment.

Risk Assessment: High-risk exposures within surgical settings have previously been defined as presence

within an operating room during aerosol-generating event, and cleaning the operating room after an aerosol-

generating procedure. Aerosol-generating procedures may include, but are not limited to, the use of saws

or other electrical devices, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, disturbance of fluids from an abscess, and high-

pressure irrigation. Risk of aerosolization subsequent to irrigation should be assessed based upon the water

pressure from the irrigation tool used. High-pressure washes and pulsed lavages are generally considered to be

high-pressure irrigation, and the use of such devices should be treated as an aerosol-generating event. While

hand bulbs are typically considered to be a low-pressure irrigation device, additional factors, like surgical

technique, should be considered before ruling out this mechanism as an aerosol-generating procedure.

13

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

Clinical Exposure

Universal precautions and personal

protective equipment (PPE) are essential

when working with body fluids or tissues

from a brucellosis patient. When standard

precautions are followed, most clinical

procedures are considered to be low-risk

activities. Higher-risk activities may include

handling of tissues with potentially high

concentrations of Brucella organisms (e.g.,

placental tissues), direct contact with

infected blood and body fluids through

breaks in the skin, or mucosal

exposure to aerosolized Brucella organisms

after an aerosol-generating procedure.

Aerosol-Generating Procedures: Aerosols

are defined as particulates (diameter < 10

µm) suspended in the air. Aerosol-generating

procedures are those that produce aerosols

as a result of mechanical disturbance of the blood or another body fluid

18

. Aerosol-generating procedures may

include, but are not limited to, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, disturbance of fluids from an abscess, the use

of saws or other electrical devices, and high-pressure irrigation. Additional information on the utilization of

electrical and irrigation devices can be found in the Surgical Exposure section below.

To the best of our knowledge, seven cases of occupationally acquired brucellosis have been reported in

the English literature among health care workers since 1990, including four infections acquired during

obstetrical delivery, and three infections through the provision of medical care to brucellosis patients. In

each case, it is likely that the health care workers were exposed through the high-risk routes of transmission

previously listed (handling of placental tissues, direct contact with infected blood/tissues, and mucosal

exposure to aerosolized Brucella).

19-21

Surgical Exposure

22, 23

In the event of a Brucella exposure during a surgical procedure, the potential risk of exposure should be

evaluated for all personnel who pass through the surgical unit. Assessments should be based on adherence

to PPE requirements, types of surgical devices utilized, risk of aerosolization, and duration of the surgical

procedure. The following paragraph, along with Table 5, may be used as a resource for risk assessment.

Risk Assessment: High-risk exposures within surgical settings have previously been defined as presence

within an operating room during aerosol-generating event, and cleaning the operating room after an aerosol-

generating procedure. Aerosol-generating procedures may include, but are not limited to, the use of saws

or other electrical devices, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, disturbance of fluids from an abscess, and high-

pressure irrigation. Risk of aerosolization subsequent to irrigation should be assessed based upon the water

pressure from the irrigation tool used. High-pressure washes and pulsed lavages are generally considered to be

high-pressure irrigation, and the use of such devices should be treated as an aerosol-generating event. While

hand bulbs are typically considered to be a low-pressure irrigation device, additional factors, like surgical

technique, should be considered before ruling out this mechanism as an aerosol-generating procedure.

Pre-Operative Recommendations for Surgery on a Brucellosis Patient:

●

The patient should be started on antibiotic therapy to decrease the bacterial load of the surrounding

tissues. Table 3 can be utilized for treatment guidance.

●

Precautions to be taken by medical staff prior to and during the operation:

Minimize aerosol-generating procedures during the surgical procedure

Only essential personnel should be present in the operating room during the procedure

All staff members present in the operating room should wear appropriate PPE, including:

❍

Gloves, masks, and eyewear

❍

Respiratory protection (e.g., N95) if there is potential for aerosol-generating procedures

Post-Operative Recommendations for Surgery on a Brucellosis Patient:

●

Evaluation of staff after potential exposure to Brucella organisms should include:

A review of appropriate PPE and possible breaches in PPE protocol during the surgical

procedure, including:

❍

Symptom and serological monitoring (as applicable) for all personnel for whom a breach of PPE

is identified.

❍

Consideration of PEP for all personnel who were present during or after a potential aerosol-

generating procedure was done.

●

Serological monitoring (as applicable) and PEP consideration for staff who are pregnant or

immunocompromised.

Workers are advised to seek medical consultation with their health care provider.

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

14

VETERINARY EXPOSURES

Vaccine Exposure

Accidental exposures to live, attenuated vaccine strains of

Brucella spp. in veterinarians have been reported via needle stick

injury, as well as through spray exposure to the conjunctiva and

open wounds. Personnel administering RB51, S19, and Rev-1

vaccinations should wear proper PPE, including gloves and eye

protection. Proper animal restraint should be used to minimize

needle sticks or conjunctival splashes.

Brucella abortus RB51 Vaccine

16, 24

The Brucella abortus RB51 vaccine is currently the only vaccine

used in the United States for prevention of brucellosis in cattle

herds. Although RB51 was developed to be less pathogenic

and abortifacient than the S19 strain in animals, it does

retain pathogenicity for humans. Local adverse events have

been reported less than 24 hours after exposure, and systemic

reactions may begin 1 to 15 days subsequent to exposure.

●

Risk Assessment: Vaccine exposures typically occur

through direct contact; therefore, all individuals exposed to

RB51 should be considered as having a high-risk exposure.

●

Symptom Monitoring: Symptom monitoring should

be emphasized following exposures to RB51 vaccine

because of the lack of serological tests available to

identify seroconversion. The symptom monitoring table in

Appendix 2 can be given to exposed individuals.

●

Antimicrobial Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP): Antibiotic post-exposure prophylaxis has been

recommended for individuals accidentally exposed to B. abortus RB51 vaccine. Refer to Table 4 for PEP

guidance. Because RB51 was derived by selection in rifampin-enriched media and is resistant to rifampin

in vitro, rifampin should not be used for PEP. The strain is also resistant to penicillin.

●

Serological Monitoring: The RB51 vaccine is a modified live culture vaccine and there are currently no

serological assays available to detect an antibody response to RB51.

Brucella abortus S19 Vaccine and Brucella melitensis Rev-1 Vaccine

25, 26

The B. abortus S19 and the B. melitensis Rev-1 animal brucellosis vaccines are available outside the U.S. and

have been known to cause systemic disease in humans. With the scope of human travel and animal trading,

potential cases in the U.S. may arise in persons exposed to the vaccine or to animals previously vaccinated.

●

Risk Assessment: Vaccine exposures typically occur through direct contact; therefore, all individuals

exposed to S19 or Rev-1 strains should be considered as having a high-risk exposure.

●

Symptom Monitoring: Guidelines for symptom monitoring can be found in Appendix 2.

●

Antimicrobial Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP): CDC recommends a concomitant prophylaxis regimen of

doxycycline and rifampin for three weeks following exposure to the S19 and Rev-1 vaccine strains. Refer to

Table 4 for PEP guidance. Rev-1 is resistant to streptomycin, and therefore this drug should not be used for

PEP or treatment courses.

25

15

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

VETERINARY EXPOSURES

Vaccine Exposure

Accidental exposures to live, attenuated vaccine strains of

Brucella spp. in veterinarians have been reported via needle stick

injury, as well as through spray exposure to the conjunctiva and

open wounds. Personnel administering RB51, S19, and Rev-1

vaccinations should wear proper PPE, including gloves and eye

protection. Proper animal restraint should be used to minimize

needle sticks or conjunctival splashes.

Brucella abortus RB51 Vaccine

16, 24

The Brucella abortus RB51 vaccine is currently the only vaccine

used in the United States for prevention of brucellosis in cattle

herds. Although RB51 was developed to be less pathogenic

and abortifacient than the S19 strain in animals, it does

retain pathogenicity for humans. Local adverse events have

been reported less than 24 hours after exposure, and systemic

reactions may begin 1 to 15 days subsequent to exposure.

●

Risk Assessment: Vaccine exposures typically occur

through direct contact; therefore, all individuals exposed to

RB51 should be considered as having a high-risk exposure.

●

Symptom Monitoring: Symptom monitoring should

be emphasized following exposures to RB51 vaccine

because of the lack of serological tests available to

identify seroconversion. The symptom monitoring table in

Appendix 2 can be given to exposed individuals.

●

Antimicrobial Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP): Antibiotic post-exposure prophylaxis has been

recommended for individuals accidentally exposed to B. abortus RB51 vaccine. Refer to Table 4 for PEP

guidance. Because RB51 was derived by selection in rifampin-enriched media and is resistant to rifampin

in vitro, rifampin should not be used for PEP. The strain is also resistant to penicillin.

●

Serological Monitoring: The RB51 vaccine is a modified live culture vaccine and there are currently no

serological assays available to detect an antibody response to RB51.

Brucella abortus S19 Vaccine and Brucella melitensis Rev-1 Vaccine

25, 26

The B. abortus S19 and the B. melitensis Rev-1 animal brucellosis vaccines are available outside the U.S. and

have been known to cause systemic disease in humans. With the scope of human travel and animal trading,

potential cases in the U.S. may arise in persons exposed to the vaccine or to animals previously vaccinated.

●

Risk Assessment: Vaccine exposures typically occur through direct contact; therefore, all individuals

exposed to S19 or Rev-1 strains should be considered as having a high-risk exposure.

●

Symptom Monitoring: Guidelines for symptom monitoring can be found in Appendix 2.

●

Antimicrobial Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP): CDC recommends a concomitant prophylaxis regimen of

doxycycline and rifampin for three weeks following exposure to the S19 and Rev-1 vaccine strains. Refer to

Table 4 for PEP guidance. Rev-1 is resistant to streptomycin, and therefore this drug should not be used for

PEP or treatment courses.

25

●

Serological Monitoring: Serological monitoring is available for S19 and Rev-1 exposures. Quantitative

serological monitoring should be emphasized to detect a B. abortus S19 infection among veterinary workers,

as patients may present with mild clinical symptoms or as asymptomatic.

26

Clinical Exposure

Veterinarians and breeders have a higher risk of contracting brucellosis because of close direct contact with

infected animals, and in part because of inconsistency in the implementation of standard precautions in

veterinary practice.

Risk of exposure is greatest when veterinarians handle aborting animals or those undergoing parturition, though

high-risk activities may also include specimen draws during clinical examination, surgical procedures, or

disinfection and cleaning of contaminated environments. Inhalation of aerosolized Brucella organisms and

contamination of the conjunctiva or broken skin are common routes of exposure during the aforementioned

high-risk procedures.

Exposure to Brucella canis

While dogs can become infected with various Brucella spp., they serve

as the primary host for Brucella canis. B. canis is thought to be less

virulent than other strains of Brucella species and few human cases

have been documented, though this may be a result of difficulty in

diagnosis and underreporting.

27

●

Symptom Monitoring: Symptom monitoring should be

emphasized following exposures to dogs infected with brucellosis

because of the lack of serological tests available to identify

seroconversion. The symptom monitoring table in Appendix 2 can

be given to exposed individuals.

●

Serological Monitoring: While serological monitoring is not

available for B. canis exposures, it is recommended that baseline

serum is drawn for serological testing to rule out titers to other

Brucella spp., as veterinary personnel may be exposed to a variety

of species.

●

Antimicrobial Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP): A prophylaxis

regimen should be considered for all personnel with high-risk

exposures. See Table 4 for PEP guidance.

Marine Mammal Exposure

28, 29

Multiple marine mammals that have been stranded in the Gulf of Mexico, Atlantic, and Pacific coasts since 2010

have had laboratory evidence of brucellosis infection. While marine-associated brucellosis in humans has not

been documented in the U.S., four human cases are known to have occurred worldwide. One individual was

exposed in a laboratory while handling samples from an infected dolphin, and three individuals became sick

after consuming raw fish or shellfish. Individuals who come in contact with marine mammals, particularly those

stranded or visibly ill, are potentially at risk for infection from B. ceti or B. pinnipedialis.

●

Risk Assessment: Higher-risk activities when working with infected marine mammals include aerosol-

generating procedures (use of saws) or cleaning of facilities with high-pressure equipment during and after

a necropsy. Failure to use PPE, including proper respiratory protection, during the aforementioned activities

places individuals at a greater risk for occupational exposure to Brucella spp. An excerpt of the Revised

Interim Marine Mammal Brucella Specific Biosafety Guidelines for the National Marine Mammal Stranding

Network is provided in Appendix 3, and may be used as a resource for post-exposure risk assessment.

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

16

●

Symptom Monitoring: Persons experiencing signs and

symptoms through 24 weeks post-exposure to infected

marine mammals are encouraged to visit their local health

care provider as soon as possible for diagnosis, informing

their doctor that they may have been exposed to an

infectious zoonotic disease such as Brucella. The symptom-

monitoring table in Appendix 2 can be distributed to

individuals who have potentially been exposed.

●

Serological Monitoring: Serologic testing for B. ceti and

B. pinnipedialis can be done with the BMAT. Baseline sera

should be drawn for individuals at high risk as soon as

the exposure is recognized, and subsequently at 6-week

intervals through 24 weeks post-exposure following the

sequence for laboratory exposures.

●

Antimicrobial Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP): Antimicrobial post-exposure prophylaxis

recommendations in the case of a marine mammal exposure are based on risk assessment for the exposed

person. See Table 4 for PEP guidance.

●

Reporting: Any human illness related to zoonotic disease exposure should be reported to the stranding

facility and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) Regional Office as soon as possible by

emailing the Regional Stranding Coordinators. The Regional Stranding Coordinators will notify the Marine

Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program (MMHSRP), who will contact the State Public Health

Veterinarian, the county and/or state department public health official and CDC.

FOODBORNE EXPOSURE

Approximately 70 to 75% of U.S. brucellosis cases

reported annually to CDC are due to B. melitensis and

B. abortus, and occur after individuals consume

unpasteurized dairy products from countries where

brucellosis remains endemic. Areas currently listed

as high-risk include: the Mediterranean Basin

(Portugal, Spain, Southern France, Italy, Greece,

Turkey, and North Africa), Mexico, South and

Central America, Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa,

the Caribbean, and the Middle East. Prevention

measures should focus on educating immigrants

and international travelers about the risks of

consuming unpasteurized dairy products from these

regions. Feral swine hunters who consume raw or

undercooked pork are also at risk for food-borne

exposure to brucellosis (via B. suis).

In cases of foodborne brucellosis, systemic symptoms are more commonly reported than gastrointestinal

complaints. A subset of patients experience nausea, vomiting, and abdominal discomfort, and rare cases of

ileitis, colitis, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis have also been reported.

30

Individuals who become sick

with a febrile illness after consumption of unpasteurized dairy products or meat from feral swine should be

encouraged to submit samples of the food for culture and PCR to confirm the route of transmission.

17

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

●

Antimicrobial Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP): Antimicrobial post-exposure prophylaxis

recommendations in the case of a marine mammal exposure are based on risk assessment for the exposed

person. See Table 4 for PEP guidance.

●

Reporting: Any human illness related to zoonotic disease exposure should be reported to the stranding

facility and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) Regional Office as soon as possible by

emailing the Regional Stranding Coordinators. The Regional Stranding Coordinators will notify the Marine

Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program (MMHSRP), who will contact the State Public Health

Veterinarian, the county and/or state department public health official and CDC.

FOODBORNE EXPOSURE

Approximately 70 to 75% of U.S. brucellosis cases

reported annually to CDC are due to B. melitensis and

B. abortus, and occur after individuals consume

unpasteurized dairy products from countries where

brucellosis remains endemic. Areas currently listed

as high-risk include: the Mediterranean Basin

(Portugal, Spain, Southern France, Italy, Greece,

Turkey, and North Africa), Mexico, South and

Central America, Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa,

the Caribbean, and the Middle East. Prevention

measures should focus on educating immigrants

and international travelers about the risks of

consuming unpasteurized dairy products from these

regions. Feral swine hunters who consume raw or

undercooked pork are also at risk for food-borne

exposure to brucellosis (via B. suis).

In cases of foodborne brucellosis, systemic symptoms are more commonly reported than gastrointestinal

complaints. A subset of patients experience nausea, vomiting, and abdominal discomfort, and rare cases of

ileitis, colitis, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis have also been reported.

30

Individuals who become sick

with a febrile illness after consumption of unpasteurized dairy products or meat from feral swine should be

encouraged to submit samples of the food for culture and PCR to confirm the route of transmission.

RECREATIONAL EXPOSURE

Feral Swine Hunting

Approximately 25 to 30% of U.S. brucellosis cases

reported annually to CDC are due to B. suis and

almost all are diagnosed in feral swine hunters

(CDC, unpublished data). Feral swine have been

reported in at least 41 states, and serologic surveys

have detected endemic feral swine infection with

B. suis in 13 states (Arkansas, California, Florida,

Georgia, Hawaii, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri,

South Carolina, and Texas). Feral swine hunting is

allowed in most states with feral swine presence.

Out-of-state hunters often bring swine meat back

to their home states; therefore cases may occur even

in regions where B. suis is not endemic in feral swine

populations.

31

Efforts to prevent B. suis infection should focus on education of hunters and partnerships between state

and local public health, wildlife and agricultural agencies, as well as sportsmen’s associations. CDC feral

swine hunter brochures are available for public dissemination and can be found in the Additional Sources of

Brucellosis Information section.

B. suis in Hunting Dogs

It is important to recognize that dogs are able to contract brucellosis from feral swine.

32

Transmission may

occur through direct contact with the swine or by consumption of uncooked pork or scraps. Non-hunting

dogs can also become infected by contact with hunting dogs through urine or breeding. Individuals who hunt

with dogs should be encouraged not to allow their dogs to play with the animal carcass or eat raw meat.

If dogs develop symptoms consistent with brucellosis (see Additional Sources of Brucellosis Information,

Brucellosis in Animals), they should be tested for Brucella spp.

BRUCELLOSIS IN PREGNANT WOMEN

Brucellosis during pregnancy carries the risk of causing spontaneous

abortion, particularly during the first and second trimesters; therefore,

women should receive prompt medical treatment with the proper

antimicrobials.

33

The most widely recommended antimicrobial therapy

for use in pregnant women is rifampin 15-20 mg/kg per day (maximum

600-900 mg/day) for 6 weeks.

14, 17, 30, 33

Rifampin is a FDA Pregnancy

Category C drug, which indicates that there are no adequate studies or

data demonstrating risk in humans, but animal studies have shown adverse

effects on the fetus from use of this drug

.34

Also, a combination therapy

regimen of rifampin 15-20 mg/kg per day (maximum 600-900 mg/day)

plus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ) 160mg-800 mg BID for

six weeks has been cited in the literature.

15, 17, 33

●

It is important to note that TMP-SMZ should not be used after 36

weeks of pregnancy because of the risk of kernicterus caused by

elevated levels of bilirubin.

14, 17

Additionally, the teratogenic potential

of many antimicrobials, including rifampin and TMP-SMZ, is unknown

in humans.

30

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

18

●

Information on doxycycline use during pregnancy is limited and FDA classifies it as a Pregnancy Category D

drug on the basis of data extrapolated from the use of tetracycline in humans and animals; FDA Pregnancy

Category D indicates that data have shown positive evidence of human fetal risk but benefits of drug use

may outweigh potential risks in certain situations.

34

For tetracyclines, infant dental staining, fetal growth

delays, and maternal fatty liver have been demonstrated. Reviews of studies of doxycycline use among

pregnant women have not demonstrated these findings.

35

The risk-benefit ratio for use of doxycycline must

be carefully considered if rifampin is unavailable or contraindicated.

●

Specific brucellosis treatment instructions should be made in consultation with the patient’s obstetrician.

PERSON-TO-PERSON TRANSMISSION

Neonatal Brucellosis

36–40

While neonatal brucellosis cases are rare, infection may occur through transplacental transmission of Brucella

spp. during a maternal bacteremic phase, from exposure to blood, urine, or vaginal secretions during delivery,

or through breastfeeding. The majority of documented neonatal brucellosis cases involve B. melitensis, though

cases of B. abortus have been reported as well.

●

Signs and Symptoms: Clinical manifestations typically resemble sepsis and include fever, resistance

to feeding, irritability, vomiting, jaundice, respiratory distress, pulmonary infiltrates, hypotension,

hyperbilirubinema, and thrombocytopenia. Progression of the disease state may be evidenced by

hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and lymphadenitis. In some cases, patients may be asymptomatic or clinical

symptoms may present later in infancy.

●

Serological Testing: Information found in peer-reviewed literature suggests that Brucella spp. may be

isolated from neonatal patients with titer levels lower than 1:160.

39, 40

●

Treatment: Dual-combination antimicrobial therapy should be administered for several weeks. Duration

and dose of treatment should be made in consultation with the patient’s neonatologist or pediatrician.

●

Prevention: As Brucella bacteremia during pregnancy carries the risk of causing spontaneous abortion

(particularly during the first and second trimester) or transmission to the infant, women who are

pregnant should avoid consuming unpasteurized dairy products and engaging in high-risk occupational

activities such as contact with infected animals or administration of live attenuated Brucella vaccines.

Prompt diagnosis and treatment is essential to secure a healthy pregnancy. Women who have been

exposed to Brucella spp. or have contracted brucellosis should consult their obstetrician for PEP

and treatment options.

19

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

●

Information on doxycycline use during pregnancy is limited and FDA classifies it as a Pregnancy Category D

drug on the basis of data extrapolated from the use of tetracycline in humans and animals; FDA Pregnancy

Category D indicates that data have shown positive evidence of human fetal risk but benefits of drug use

may outweigh potential risks in certain situations.

34

For tetracyclines, infant dental staining, fetal growth

delays, and maternal fatty liver have been demonstrated. Reviews of studies of doxycycline use among

pregnant women have not demonstrated these findings.

35

The risk-benefit ratio for use of doxycycline must

be carefully considered if rifampin is unavailable or contraindicated.

●

Specific brucellosis treatment instructions should be made in consultation with the patient’s obstetrician.

PERSON-TO-PERSON TRANSMISSION

Neonatal Brucellosis

36–40

While neonatal brucellosis cases are rare, infection may occur through transplacental transmission of Brucella

spp. during a maternal bacteremic phase, from exposure to blood, urine, or vaginal secretions during delivery,

or through breastfeeding. The majority of documented neonatal brucellosis cases involve B. melitensis, though

cases of B. abortus have been reported as well.

●

Signs and Symptoms: Clinical manifestations typically resemble sepsis and include fever, resistance

to feeding, irritability, vomiting, jaundice, respiratory distress, pulmonary infiltrates, hypotension,

hyperbilirubinema, and thrombocytopenia. Progression of the disease state may be evidenced by

hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and lymphadenitis. In some cases, patients may be asymptomatic or clinical

symptoms may present later in infancy.

●

Serological Testing: Information found in peer-reviewed literature suggests that Brucella spp. may be

isolated from neonatal patients with titer levels lower than 1:160.

39, 40

●

Treatment: Dual-combination antimicrobial therapy should be administered for several weeks. Duration

and dose of treatment should be made in consultation with the patient’s neonatologist or pediatrician.

●

Prevention: As Brucella bacteremia during pregnancy carries the risk of causing spontaneous abortion

(particularly during the first and second trimester) or transmission to the infant, women who are

pregnant should avoid consuming unpasteurized dairy products and engaging in high-risk occupational

activities such as contact with infected animals or administration of live attenuated Brucella vaccines.

Prompt diagnosis and treatment is essential to secure a healthy pregnancy. Women who have been

exposed to Brucella spp. or have contracted brucellosis should consult their obstetrician for PEP

and treatment options.

Sexual Transmission

41-48

Since 1966, there have been nine case reports published

in English literature that document evidence of person-to-

person transmission of brucellosis. In each of the cases,

a male patient who presented symptoms consistent with

brucellosis was thought to have transmitted Brucella spp.

to a female partner via sexual intercourse. Although rare,

it is important to recognize that sexual partners of infected

patients may be at risk for exposure to brucellosis.

Organ Donations and Blood Transfusions

While uncommon, transmission of Brucella spp. may also

occur via tissue transplantation or blood transfusions.

There are few reported cases of brucellosis caused by

blood transfusion, the earliest dating from 1955 and all

occurring outside of the United States.

49,50

There are several

reports of transmission due to transplantation, two of

which are attributed to bone marrow donation between

siblings.

51,52

In other published reports of brucellosis in

transplant recipients, it is difficult to ascertain if infection

was acquired from the transplant or through other modes

of infection.

53,54

If a patient who has undergone a recent

transfusion or transplant develops symptoms consistent

with brucellosis, the CDC Office of Blood, Organ, and

Other Tissue Safety should be contacted for assistance

with trace-back investigations.

PREVENTION

Occupational Exposures

Exposures to Brucella spp. can occur in occupational environments, which include but are not limited to:

laboratories, clinical and surgical settings, and veterinary settings. In cases involving high-risk exposures (see

Table 4 for risk assessment), post-exposure antimicrobial prophylaxis is recommended.

Clinicians should inform laboratory personnel when patient specimens are suspect or rule-outs for brucellosis.

Laboratory personnel should work with Brucella spp. in at least a class II Biological Safety Cabinet (BSC), with

proper personal protective equipment (PPE) and use of primary and secondary barriers, in compliance with

the Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL), which provides information and

recommendations on laboratory containment methods and microbiological procedures. When working with

Brucella spp. or other infectious organisms, ensure procedures are in place to minimize risk of exposure through

spills, splashes, and aerosol-generating events.

In clinical, surgical, and veterinary settings, procedures should also be performed judiciously to minimize

spills, splashes, and aerosols.

22

Depending on the types of procedures that are performed, PPE should include

adequate protection to minimize direct contact (to skin and mucous membranes) and aerosol exposures.

Examples of appropriate PPE include gloves, closed footwear, eye protection, face shield (as necessary,

depending on procedure), and respiratory protection (as necessary, depending on procedure).

Brucellosis Reference Guide: Exposures, Testing, and Prevention

20

Recreational Exposures (Hunter Safety)

Hunting wild animals carries with it the potential for risk

of exposure to infectious diseases. Certain wild animals

(e.g., feral swine, elk, moose, bison, deer, caribou) can

carry brucellosis and be a source of transmission. Predatory

animals may also be prone to brucellosis after feeding on

infected animals. When hunting, it is important to avoid

contact with animals that are found dead or are otherwise

visibly ill. Animals that appear to be healthy can still have

brucellosis; in these cases, safe field dressing techniques can

help protect hunters.

●

Use clean, sharp knives for field dressing and butchering.

●

Wear eye protection and nonporous, disposable gloves

(e.g., rubber, nitrile, or latex gloves) when handling

carcasses.

●

Avoid direct (bare skin) contact with fluid or organs

from the animal.

●

Avoid direct (bare skin) contact with hunting dogs that

may have come into contact with hunted animals.

●

After butchering, burn or bury disposable gloves and

parts of the carcass that will not be eaten.

●

Do not feed dogs with raw meat or other parts of the

carcass.

●

Wash hands as soon as possible with soap and warm

water for 20 seconds or more. Dry hands with a clean

cloth.

●

Clean all tools and reusable gloves with a disinfectant,

like dilute bleach (Follow the safety instructions on the product label).

●

Thoroughly cook meat from any animal that is known to be a possible carrier of brucellosis.

●

Be aware that freezing, smoking, drying and pickling do not kill Brucella.

This information can be found on the CDC Hunter Safety web feature.

Travel to Endemic Areas

Brucellosis is endemic in many parts of the world. High-risk areas include: Mexico, South and Central America,

Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean Basin (Portugal, Spain,

Southern France, Italy, Greece, Turkey, and North Africa). When traveling to these areas, be cautious of and

avoid contact with livestock and consumption of raw animal products. Consumption of raw or undercooked

meat, as well as raw or unpasteurized dairy products, can result in transmission of Brucella and potentially lead

to illness.

See CDC Brucellosis – Areas at Risk.

21