Primary Care Expenditures

Summary of current primary care expenditures

and investment in Washington

Report to the Legislature

As required by Chapter 415, Laws of 2019

Forecasting and Research

Office of Financial Management

December 2019

Contents

Executive summary ............................................................................................. 1

Background ......................................................................................................... 2

Approach to estimate primary care spending ....................................................... 3

Results ................................................................................................................ 7

Previous research on primary care .................................................................... 11

Non-claims-based expenditures ........................................................................ 12

Limitations of current report ............................................................................... 16

Future considerations ........................................................................................ 18

Conclusion ........................................................................................................ 18

References ........................................................................................................ 20

Appendix A: Budget proviso .............................................................................. 22

Appendix B: Primary Care Expenditures Stakeholder Group ............................. 23

Appendix C: List of providers ............................................................................. 24

Appendix D: Procedure codes ........................................................................... 27

Primary Care Expenditures Report 1

Executive summary

This is the first comprehensive analysis of annual primary care medical expenditures in Washington.

In the 2019–21 biennial budget, the Legislature directed the Office of Financial Management to

determine annual primary care medical expenditures as a percentage of total medical expenditures by

carrier. This report summarizes the approach and data sets used to calculate these expenditures,

compares and contrasts the methods and results with other state and national reports on primary

care medical expenditures, and discusses limitations to current data sources.

OFM, working with key stakeholders representing different areas of primary care practitioners,

created a definition for primary care providers and services that takes into account the range of

interpretations of primary care. A narrow and broad definition of providers and services were

created, and then claims meeting the service and provider definitions were used to calculate primary

care expenditures. This approach ensured expenditures attributed to primary care services were

incurred by primary care providers. Expenditures were calculated using cost information from the

Washington All-Payer Health Care Claims Database.

In Washington for 2018, primary care expenditures as a percentage of total medical

expenditures ranged from 4.4% (about $838 million) to 5.6% (about $1 billion) based on

either a narrow or broad definition, respectively, of primary care. Primary care spending

as a percentage of total spending was highest for people under 18 years and lowest in

people 65 years and older.

With respect to market sector: Similar percentages of primary care spending were seen in public

employee, Medicaid managed care and commercial coverage. Medicare Advantage had the lowest

percentage, reflecting differences already seen by age. Differences in primary care spending by

health care company and market sector vary considerably and could be influenced by the needs of

the population covered (average age, sex, comorbidity and geography).

This report’s estimates for the proportion of medical expenditures attributable to primary care

appears smaller than estimates calculated in other reports. Because there is no national standard for

how to measure primary care expenditures, however, these estimates cannot be compared directly

because of differences in data sets, methodologies and definitions of primary care. When comparing

Washington’s proportion of primary care spending with reports from Oregon and Rhode Island, the

differences in approaches and definitions of primary care make these types of comparisons

challenging. For instance, Washington included pharmacy claims in its total medical expenditures

while Oregon did not. Washington and Oregon also differed in their methods for capturing costs of

primary care services. Oregon and Rhode Island included non-claims-based expenditures in their

total primary care spending which are not included in Washington’s estimates. An overview of the

non-claims-based expenditures collected by Oregon and Rhode Island is included in this report, in

addition to examples for future consideration in data collection efforts for Washington.

This report highlights a low rate of investment in primary care in Washington and, as a baseline, can

be used to monitor future spending. Research has shown health care systems with higher

proportions of investments oriented toward primary care have better health outcomes and lower

costs. Monitoring the impact of policies and system performance will be key to successfully

strengthening Washington’s primary care system.

Primary Care Expenditures Report 2

Background

In the 2019–21 biennial operating budget, Chapter 415, Laws of 2019,

1

the Legislature directed the

Office of Financial Management to conduct a study to determine annual primary care medical

expenditures as a percentage of total medical expenditures in Washington (Appendix A). Having an

estimate of primary care expenditures, in addition to reports on the primary care workforce,

enhances the state’s understanding of the current level of investment in primary care (Yen, 2018).

With a baseline of primary care spending, the state will have better:

• Benchmarking of spending and investments on primary care;

• Tracking of efforts to increase primary care spending;

• Measurement of the impacts of payment reform;

• Focus of interventions to increase patient access to primary care; and

• Information to compare to other states’ efforts to increase primary care spending.

Similar reports have been completed in Oregon and Rhode Island; efforts are underway in other

states to understand primary care spending levels to guide new investments.

As required in the proviso, OFM convened a group of stakeholders (Appendix B) representing

family practice, general internal medicine, general pediatrics and the state Health Care Authority to

advise on the parameters for estimating primary care expenditures for the state.

The stakeholder group worked with OFM to answer the following questions:

• Who are primary care providers?

• What are primary care services?

• What percentage of total health care expenditures is currently allocated to primary care?

• How does this percentage differ by health insurance carrier?

• What information about primary care is not captured by current data sources?

OFM also contacted researchers in Oregon and Rhode Island, and from other institutions who

worked on similar primary care expenditure reports, to discuss methodology and gather advice for

pursuing the Washington report.

The goals for Washington’s primary care expenditure report are to:

• Conduct a transparent process for determining what providers and services are

considered primary care;

• Develop a transparent and detailed methodology that can be replicated to measure

trends and changes in primary care spending in future years;

• Discuss differences between Washington’s methodology and results compared with

other estimates and reports;

• Identify barriers to accurately estimating primary care expenditures; and

• Provide suggestions and guidance for future tracking of primary care spending and

iterations of this type of report.

OFM intends for this report to be the baseline for tracking and monitoring new investments and

initiatives to increase primary care spending in Washington. This report can help frame discussions

1

http://lawfilesext.leg.wa.gov/biennium/2019-20/Pdf/Bills/Session%20Laws/House/1109-S.SL.pdf

Primary Care Expenditures Report 3

on what additional information will be beneficial for understanding primary care needs and how to

measure outcomes of increasing primary care spending.

But first, we must start with a definition of primary care.

What is primary care?

Primary care as defined by the National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine):

“… is the provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable

for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs including physical, mental, emotional,

and social concerns, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context

of family and community (Donaldson, M.S., Yordy, K.D., Lohr, K.N., & Vanselow, N.A., 1996).”

This definition has been used to measure how well four main features of primary care services are

fulfilled (Starfield, B., Shi, L., Macinko, J., 2005):

• First-contact access (into the health care system) for each new need

• Long-term person- (not disease-) focused care (also referred to as continuous care)

• Comprehensive care for most health needs

• Coordinated care when it must be sought elsewhere

Investing in primary care and ensuring access to primary care can reduce health care costs by

lowering rates of preventable emergency department visits, hospital admissions and specialist visits

(Friedberg, Hussey, & Schneider, 2010; Glass, Kanter, Jacobsen, & Minardi, 2017; Starfield, B.,

Shi, L., Macinko, J., 2005). Primary care helps to achieve health equity by providing access to health

services and promotes care at the most appropriate level (Starfield, 1998) and, as a result, can reduce

premature mortality (Basu et al., 2019; Starfield, B., Shi, L., Macinko, J., 2005). Internationally, health

systems with higher proportions of health care spending on primary care have better health

outcomes and lower health care costs (Friedberg et al., 2010; Jabbarpour, Y., Greiner, A., Jetty, A.,

Coffman, M., Jose, C., Petterson, S., 2019; OECD, 2017).

Many states are implementing strategies to improve primary care investment by adopting patient-

centered medical home incentives or other value-based care models; focusing on social determinants

of health; expanding the primary care workforce and infrastructure; or increasing rates for primary

care providers.

Approach to estimate primary care spending

OFM contracted with Onpoint Health Data to estimate primary care expenditures using the state-

run Washington All-Payer Health Care Claims Database, or WA-APCD. Onpoint Health Data is the

data vendor for the WA-APCD, which was established by OFM through legislation passed in 2014.

Launched in the summer of 2018, the WA-APCD contains pharmacy, medical and dental claims

along with eligibility information. It is the most comprehensive source of claims data in the state

with more than 6 million covered lives from more than 50 commercial, Medicaid and Medicare

payers. Self-insured (not covered by state public employee benefits), federal insurance and Veterans

Benefits Administration claims are not included in the database. The WA-APCD contains cost

information, including billed, allowed and paid amounts that allow for calculations of total and

primary care expenditures. Data from 2014 through the third quarter of 2019 are included in the

database; submissions from carriers are completed on a quarterly basis and validated on a yearly

basis. Data from calendar year 2018 were used for this report.

Primary Care Expenditures Report 4

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

As per the budget proviso, total medical expenditures excluded dental care, but included costs of

prescription drugs. The proviso also called for vision care to be excluded, but it was unclear what

types of vision services should be excluded (e.g., eyeglasses, cataract surgery, glaucoma testing).

Many commercial insurance plans lack vision coverage, but because vision services are not

submitted separately from medical claims to the WA-APCD (unlike dental claims that are a separate

submission), it was determined for this report to leave vision services as part of total medical

expenditures.

Only claims paid using the member’s primary insurance are included in the calculations for

expenditures. Claims paid using a secondary insurance or payer were not included to avoid double

counting expenditures. Only members who had a medical or pharmacy claim paid in 2018 are

included in the analysis, limiting the members who are included. According to the National Health

Interview Survey, about 16% of adults did not have contact with a doctor or other health care

professional in the past year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019).

Additionally, Medicare fee-for-service data were excluded from this report because the 2018 data

will not be available until 2020. Medicaid fee-for-service data were excluded due to errors in

submission to the WA-APCD, and health care claims from Coordinated Care for Medicaid managed

care were excluded because labeling of its claims in the submission process made it difficult to

distinguish if claims were paid as a primary or secondary payer.

Oregon and Rhode Island included estimates of non-claims-based expenditures for primary care,

which are usually self-reported by the individual insurance carriers in the state, in their reports on

primary care spending. Currently, there is no process in Washington to collect this type of

information from all commercial carriers. The Health Care Authority collects information from the

Medicaid managed care organizations and the public employee benefits carriers for managed care

rate development, and is developing processes to collect non-claims information for future

contracts. OFM was unable to access this information for this report. Suggestions for future data

collection of non-claims-based expenditures are outlined later in this report.

Defining primary care claims

Identifying primary care services in claims data is not straightforward. Most analyses of primary care

expenditures using claims data must construct a definition for primary care provider and primary

care services. There are several reasons for this approach:

• Identifying primary care clinics or offices in claims data is difficult because there is no field

or value that indicates primary care as a setting of care.

• Providers who list primary care as their specialty may work in a variety of places, some of

which would not be considered a traditional primary care setting (e.g., hospitalists in in-

patient settings or nurse practitioners working in a specialist’s office) or may be delivering

nonprimary care services.

• Some primary care services may be delivered by specialists or others who would not be

defined as a primary care provider (e.g., a cardiologist ordering a basic lab test).

• Some institutions (e.g., Federally Qualified Health Center) may submit both a facility and

professional claim for primary care services depending on the health insurance company,

and the provider identification on these types of claims may be different.

Primary Care Expenditures Report 5

As a first step for this analysis, separate definitions of primary care provider and primary care

services were determined and then claims meeting both definitions were included as primary care

expenditures. This approach follows the concepts of the Primary Care Spend Model to narrow

primary care services to those that are performed specifically by primary care providers (Baillieu et

al., 2019).

Primary care providers

Washington does not have a roster or other data source identifying individual providers who are

practicing in primary care settings. Some health insurance companies may have a listing of providers

delivering primary care, but it is not included in claims submissions to the WA-APCD. There is also

no agreed-upon definition used in the literature to define primary care providers. Some of the

variation in definition is due to the availability of different data sources that may or may not include

certain types of providers (e.g., homeopaths).

The stakeholder group began by reviewing taxonomy codes, which are used to categorize health care

providers by their specialization, and descriptions included in the 2019 Primary Care Spending in

Oregon report (Oregon Health Authority and the Department of Consumer and Business Services,

2019). The stakeholder group decided upon two groups of providers (Appendix C):

• Narrow definition: representing providers who traditionally perform roles contained within

strict definitions of primary care

• Broad definition: representing providers who perform roles not traditionally contained

within a strict definition of primary care (e.g., obstetricians)

This approach is similar to other reports on primary care expenditures (Bailit, Friedberg, & Houy,

2017; Jabbarpour, Y., Greiner, A., Jetty, A., Coffman, M., Jose, C., Petterson, S., et al., 2019; Reid,

Damberg, & Friedberg, 2019), but was not the approach taken in the Oregon report. Results for

both the narrow and broad definitions of primary care providers are included in this report.

Taxonomy codes for the narrow definition of primary care provider are family medicine, internal

medicine, Federally Qualified Health Center, general practice, naturopath, pediatrics, preventive

medicine, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, primary care clinic and rural health clinic. The

broad definition of providers included behavioral health providers, clinical nurse specialist,

registered nurse, midwives, obstetrics and gynecology, family medicine and pediatric subspecialties,

homeopath, psychiatry and neurology, psychologist, registered nurse and social worker.

Primary care services

Primary care procedures or services were defined using the American Medical Association’s Current

Procedure Terminology, or CPT, and the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System, or

HCPCS. For this report, the stakeholder group began by reviewing the list of primary care

procedure codes included in the Oregon report and added services (e.g., additional preventive

medicine screenings) based on various works stakeholders had completed in other areas. Both a

narrow and broad list of services were considered for estimating primary care. Many of the services

included in the broad definition reflected services that were specific to provider taxonomies included

in the broad definition of primary care provider (e.g., obstetricians and care following a cesarean

delivery). Inpatient visits billed by primary care providers using a CPT or HCPC inpatient code were

not included in either the broad or narrow definition of primary care services. The stakeholder

group did not feel that these types of visits represented traditional primary care (e.g., first-contact

access, continuous, comprehensive, coordinated) or getting people the right care in the right setting.

In many instances, it’s difficult to identify which services on claims were performed by a primary

Primary Care Expenditures Report 6

care provider in inpatient hospital settings. Emergency department visits billed by a primary care

practitioner were also not included for similar reasons.

Other reports on primary care expenditures have used one definition for primary care services cross-

walked with different definitions for primary care providers (Bailit et al., 2017; Jabbarpour, Y.,

Greiner, A., Jetty, A., Coffman, M., Jose, C., Petterson, S., 2019). Reid et al (Reid et al., 2019) used

both a narrow and broad definition for primary care providers in combination with a narrow

definition for primary care services and then again with all professional services.

This report contains the results from both the narrow and broad definition of primary care services.

Examples of primary care procedure codes are those for routine medical exams, preventive medicine

services, screening for diseases, vaccine administration and newborn care services (Appendix D).

Expenditure calculations

Expenditures for health care services were calculated using the total allowed amount submitted on

claims to the WA-APCD. The total allowed amount includes the health insurance plan paid amount

plus any deductibles, coinsurance or copays paid by the patient. For insurance companies that pay

providers using capitated payment arrangements (e.g., a per-member per-month payment), the fee-

for-service equivalent amount is submitted to the WA-APCD and used as the paid amount for that

health care service.

Total health care expenditures comprised all medical claims (including in-patient hospitalizations)

and pharmacy claims. With respect to immunizations: Although vaccines are included in the total

health care expenditures calculations, only the costs associated with administering the vaccine, if

administered by a primary care provider, were included in primary care expenditures. Expenditures

for primary care services provided by primary care providers were aggregated by provider specialty

and then summed across all provider groupings to estimate total primary care expenditures.

Although Appendix C (List of Providers) lists a large number of behavioral health specialist

taxonomy codes, when primary care service codes were applied, most claims and associated

expenditures for these providers were not included in primary care expenditures.

All nurse practitioner and physician assistant taxonomy codes were included in this report.

Adjustments were made to the total primary care expenditures calculated for these providers. These

adjustments (41% for nurse practitioners and 34% for physician assistants) were needed because

many nurse practitioners and physician assistants may have a provider taxonomy code included in

the definition for a primary care provider, but actually provide care in other settings (e.g., surgical).

Because claims data do not indicate if a health care setting is primary care, the adjustment factors

were needed to avoid overestimating primary care expenditures by counting services for nurse

practitioners or physician assistants that were not conducted in primary care settings. These

adjustments were based on recommendations from the stakeholder group and studies conducted by

the Washington State University College of Nursing (Kaplan & Gill, 2018) and the Washington

Medical Commission (Washington Medical Commission, 2019).

Primary care services for people without insurance and services paid with cash by patients who did

not file an insurance claim were not included in the analyses.

Calculations for carriers

More than 50 commercial, Medicare and Medicaid data suppliers submit claims data to the WA-

APCD. Data are submitted either at the company level or at the individual health insurance plan

level, depending upon how the company’s claims processing system is set up and the number of

Primary Care Expenditures Report 7

health insurance plans issued in the state. Plans were first grouped by market sector (commercial,

public employee benefits, Medicaid managed care organizations and Medicare Advantage) and then

rolled up to the company level. Primary care and total expenditures were calculated at the company

level within each market sector. Companies that had fewer than 1,000 covered persons were

excluded from analyses. Dental companies were also excluded, and only medical and pharmacy

claims from 2018 were used.

Results

Monthly enrollment

Included in this report is claims information for more than 1.2 million Medicaid managed care

organization members, more than 1.1 million commercial members, and more than 300,000 public

employees and 300,000 Medicare Advantage members. The total amount of health care spending

captured in the WA-APCD for this report for 2018 was almost $19 billion, 21% of which was for

pharmacy claims.

In 2018, overall investments in primary care as a total of all medical expenditures for Washington

ranged from 4.4% to 5.6%, depending on whether a narrow or broad definition of providers and

services were used (Figure 1). Limiting the definition of primary care providers and procedures to

narrow definitions each resulted in approximately $838 million in claims. Including the broad

category of procedures resulted in about $50 million more and an increase in the primary care share

to 4.7% of total medical expenditures. Including a broad definition of providers, in addition to a

broad definition of procedures, increased primary care expenditures by about $169 million and

resulted in a 19% increase in primary care expenditures, but overall, the total percentage of all health

care expenditures specific to primary care was only 5.6%.

Figure 1. Summary of Medical Expenditures in Washington State, 2018

Pharmacy

$3,862M

(20.5%)

Other Medical

$13,955M

(73.9%)

Broad Provider &

Broad Procedure

$169M (0.9%)

Narrow Provider &

Broad Procedure

$50M (0.3%)

Narrow Provider &

Narrow Procedure

$838M (4.4%)

Primary Care

(5.6%)

Primary Care Expenditures Report 8

This highest percentage of primary care spending was for individuals younger than 18 years, ranging

from 10.4% to 11.2% of about $2 billion in total medical expenditures for the narrow (narrow

definition of providers and narrow definition of procedures) and broad (broad definition of

providers and broad definition of procedures) definitions of primary care, respectively (Figure 2). Of

working age adults aged 18 to 64 years, the percentage of primary care spending ranged from 3.8%

to 5.4% of about $11 billion in total medical expenditures. It should be noted that this age group

could be affected the most by the inclusion of obstetrics in the broad definition of primary care. For

adults aged 65 and older, primary care spending was 3.5% to 4% of about $5.5 billion in total

medical spending. Older adults have a higher rate of hospital inpatient stays and other costs outside

of primary care because of the higher prevalence of chronic and comorbid conditions and greater

use of specialists.

Figure 2. Primary Care as Percentage of Total Expenditures by Age

4.4% 5.6%

10.4% 11.2%

3.8% 5.4%

3.5% 4.0%

Statewide

Age < 18

Age 18-64

Age >= 65

% PC narrow

% PC broad

Primary Care Expenditures Report 9

Considering primary care expenditures by market sector, public employee coverage had the highest

percentage of primary care spending, ranging from 5.8% to 7.3% of about $1.8 billion in 2018

(Figure 3). Medicaid managed care organizations ranged between 5.1% to 6.8% of about $4 billion in

2018; commercial plans ranged between 4.5% and 5.7% of about $8 billion; and Medicare

Advantage plans ranged from 3.4% to 3.9% of about $5 billion in total claims. Some of these

differences in primary care spending reflect differences in patient characteristics between market

sectors. Additionally, primary care spending for public employee coverage may be overestimated

because many of the pharmacy claims were not designated for public employees when submitted to

the WA-APCD. This would result in lower total expenditures for this group.

Figure 3. Primary Care as Percentage of Total Expenditures by Market Sector

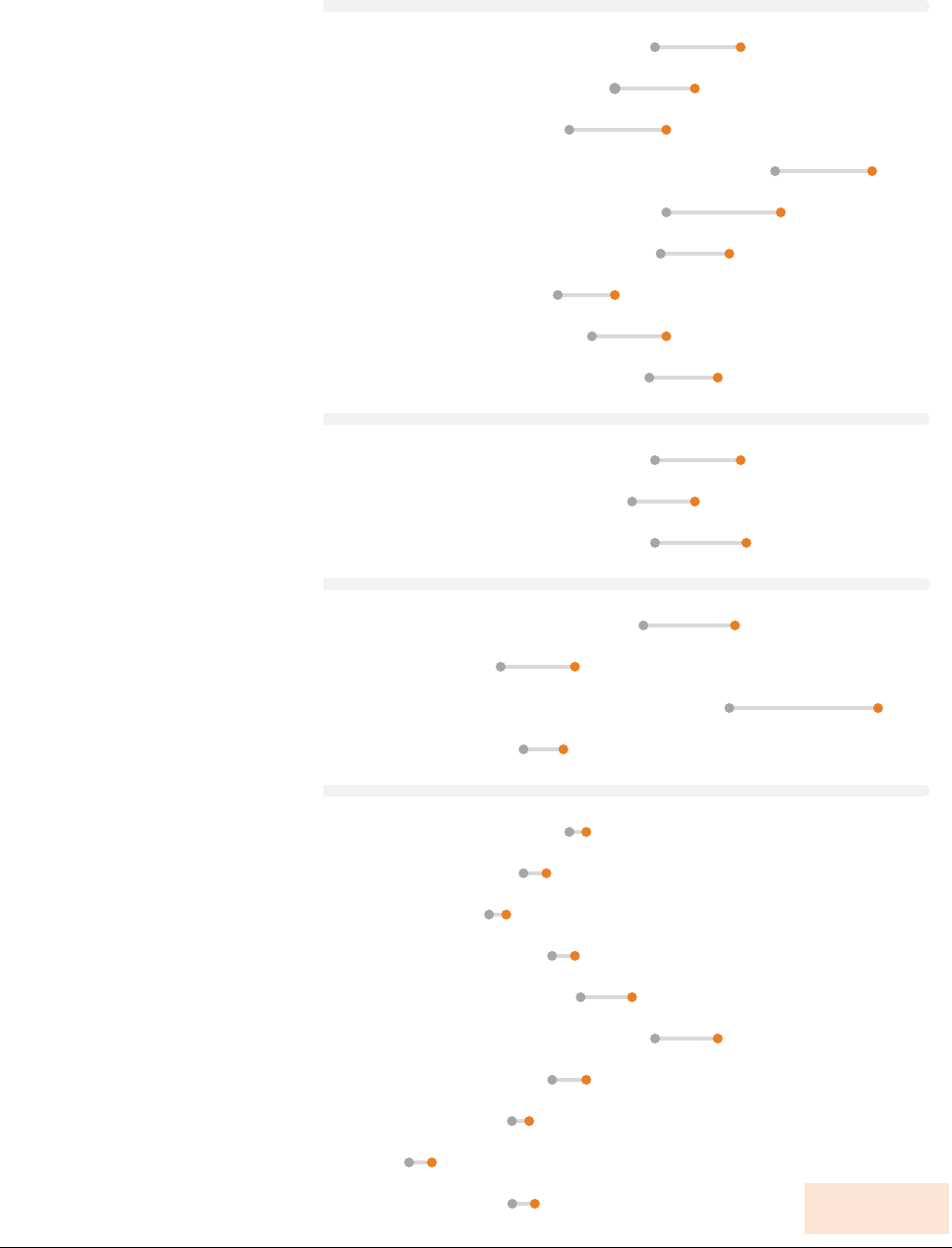

Of commercial plans, the percentage of primary care investment as a total of all medical

expenditures ranged from 4.1% to 5.1% for Premera Blue Cross to 7.9% to 9.6% for Kaiser

Foundation Health Plan of the Northwest. For public employee plans in the Public Employee

Benefits Board program, the range of primary care spending was very similar among the three

companies. For Medicaid managed care plans, the percentage of primary care spending as a total of

all medical expenditures ranged from 3.1% to 4.4% for Community Health Plan of Washington to

7.1% to 9.7% for Molina Healthcare. For Medicare Advantage plans, the percentage of primary care

investment was less than 7% for all plans (Figure 4). Even within market sector, caution should be

exercised in comparing expenditures by health plan or company because of differences in

characteristics of enrollees that are not adjusted for in these analyses.

4.5% 5.7%

5.8% 7.3%

5.1% 6.8%

3.4% 3.9%

Commercial

PEBB

Medicaid managed care

Medicare Advantage

% PC narrow

% PC broad

Primary Care Expenditures Report 10

5.8% 7.3%

5.1% 6.5%

4.3% 6.0%

7.9% 9.6%

6.0% 8.0%

5.9% 7.1%

4.1% 5.1%

4.7% 6.0%

5.7% 6.9%

5.8% 7.3%

5.4% 6.5%

5.8% 7.4%

5.6% 7.2%

3.1% 4.4%

7.1% 9.7%

3.5% 4.2%

4.3% 4.6%

3.5% 3.9%

2.9% 3.2%

4.0% 4.4%

4.5% 5.4%

5.8% 6.9%

4.0% 4.6%

3.3% 3.6%

1.5% 1.9%

3.3% 3.7%

COMMERCIAL*

Aetna Life Insurance Co.

Cambia Health Solutions

Cigna

Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of the NW

Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of WA

Molina Healthcare

Premera Blue Cross

Providence Health Plan

UnitedHealthcare

PEBB

Cambia Health Solutions

Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of NW

Kaiser Foudation Health Plan of WA

MEDICAID MANAGED CARE ORGANIZATIONS*

Amerigroup Washington, Inc.

Community Health Plan of WA

Molina Healthcare

United Health Care

MEDICARE ADVANTAGE

Aetna Life Insurance Co.

Cambia Health Solutions

Community Health Plan of WA

Humana

Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of the NW

Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of WA

Molina Healthcare

Providence Health Plan

Soundpath Health

UnitedHealthcare

Figure 4. Primary Care as Percentage of Total Expenditures by Carrier or Company

% PC narrow

% PC broad

* Data for Coordinated Care are not listed due to data issues.

Primary Care Expenditures Report 11

Previous research on primary care

There have been a number of efforts to estimate primary care spending as a proportion of total

health care spending. While Washington’s estimates might appear low, these estimates cannot be

compared directly with other published studies. Indeed, there is no national standard for how to

measure primary care expenditures. As a result, estimates between reports may differ as a result of

different definitions of primary care, different data sets used in analyses, different populations

included in data sets and different methodologies to estimate primary care spending.

The Robert Graham Center, using survey data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, or

MEPS, estimated that Washington spends between 5.9% and 10.1% of health care expenditures on

primary care (depending on whether a narrow or broad definition of primary care provider is used)

(Jabbarpour, Y., Greiner, A., Jetty, A., Coffman, M., Jose, C., Petterson, S., 2019). While this study

used a standardized measure (MEPS data) to compare primary care spending across states, it does

have some limitations. The definition of primary care used in the analysis was based only on the

taxonomy of the provider without taking into account the particular health care services performed,

which may have resulted in an overestimate of actual primary care spending. Furthermore, nurses,

nurse practitioners and physician assistants were included as primary care providers irrespective of

whether they practiced in primary care settings because that information cannot be ascertained in the

MEPS data. In addition, some MEPS data is self-reported and may be subject to recall bias.

The Milbank Memorial Fund undertook a proof-of-concept study to assess the feasibility of

calculating primary care spending using commercial claims data (Bailit et al., 2017). The study used

national data and found that 7.1% to 8.6% of total health care spending was specifically primary

care-related. Differing interpretations of how to calculate primary care spending may have occurred,

however, because each health insurance carrier calculated and submitted its data independently.

A recent report in the Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine using claims

data estimated about 2% to 4% of total medical and prescription drug spending for Medicare fee-

for-service beneficiaries was for primary care (Reid et al., 2019). In comparison, while this report

does not include Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, it does include Medicare Advantage

members; these estimates as a market sector were between 3.4% and 3.9%.

Oregon and Rhode Island routinely produce reports estimating primary care spending. For 2017,

Oregon estimated the percentage of total medical spending for primary care was:

• 16.5% for coordinated care organizations

• 13.4% for commercial carriers

• 12.2% for Medicare Advantage

• 10.6% for public employees and educators benefits

Rhode Island estimated primary care spending for its commercial plans to be close to 9.1% (in

2012), an increase of 3.5% from 2008.

It is difficult to compare Washington’s proportion of primary care spending to Oregon’s or Rhode

Island’s estimates due to differences in approaches and definitions of primary care. For example,

Oregon did not include any health care spending by patients such as copay, coinsurance or

deductibles while these were included in Washington’s estimates. Oregon also excluded prescription

drugs from its estimates of total claims-based payments or total medical expenditures. Per the

budget proviso, this report included all pharmacy claims costs in total medical expenditures, which

would make the percentage of primary care spending in Washington appear smaller than if these

Primary Care Expenditures Report 12

claims had been excluded. For this report, only claims paid by the primary payer are included in the

calculations to avoid any duplications of cost. It is not clear whether Oregon and Rhode Island

employed this same strategy.

Additionally, Washington’s estimates do not include non-claims-based expenditures, which are

included in estimates for Oregon and Rhode Island. When limiting Oregon’s primary care spending

to just claims-based, the estimated percentage of total medical spending for primary care for 2017

was closer to Washington’s estimates:

• 6.6% for coordinated care organizations

• 7.3% for commercial carriers

• 3.6% for Medicare Advantage

• 8% for public employees and educators benefits

Excluding non-claims-based estimates from this report produces a smaller overall estimate for

Washington, although some of these included in other states may not be exclusive to primary care.

For Oregon, many of the non-claims-based expenditures were capitated salaries for primary care or

provider incentive payments. Because Washington uses a fee-for-service equivalent for capitated

payments, the methods used in this report could be capturing some of the non-claims-based

payments that Oregon reported separately in its total.

Non-claims-based expenditures

Many services and activities are needed to fulfill the four main features of primary care services

(first-contact, continuous, comprehensive and coordinated care). These activities are not always

captured in fee-for-service expenditures submitted on health care claims. Non-claims-based

expenditures may occur in a provider’s office, be delivered by health care companies or be part of

government initiatives. Because of the broad nature of these types of activities, these investments

may not be specific to primary care (e.g., health information technology) or may be unique to certain

health care systems and populations. Collecting non-claims-based primary care expenditure

information in a standard way across payers will be difficult with current data sources. Clear

guidelines, definitions and reporting requirements, along with a critical examination of what non-

claims-based investments will benefit the delivery of primary care specifically (versus the cost of

business), should be included in future discussions on primary care expenditures.

Oregon and Rhode Island included a variety of non-claims-based expenditures in their primary care

spending estimates. Originally, Rhode Island had a requirement from its Office of the Health

Insurance Commissioner’s Affordability Standards that all commercial insurers allocate at least 35%

of their total spending on primary care to non-claims-based (Rhode Island referred to these as non-

fee-for-service) payments increasing to 40% in 2014. While these targets were retired in 2015, the

aggregate value of non-fee-for-service investments in primary care has continued to increase (King,

2019).

Non-claims-based expenditures included incentive payments to providers or practices, health

information technology investments such as health insurance exchanges, expansion of primary care

workforce with supplemental staff and other investments. Oregon and Rhode Island collected this

information directly from their health plans using Excel templates. Oregon included in rule the

definitions for non-claims-based primary care expenditures

2

and gave additional guidance in its

2

https://secure.sos.state.or.us/oard/viewSingleRule.action?ruleVrsnRsn=260735 Accessed Oct 2019.

Primary Care Expenditures Report 13

reporting templates on how to consider what expenditures to report. Rhode Island’s Office of the

Health Commissioner collects the non-claims-based information through its Affordability Standards

program, which aims to lower costs and improve quality. This program includes investment

requirements like patient-centered medical homes, but also allows for insurance companies to

submit expenditures for other types of investments for primary care (e.g., loan repayment).

Washington has no process to collect non-claims-based information from all plans that submit

claims to the WA-APCD, nor has the state developed any universal guidance or definitions of non-

claims-based expenditures. Some information outside of fee-for-service payments is submitted

through the Medicaid managed care rate development process for Medicaid and the Public

Employees Benefit Board. The Health Care Authority is developing a process to collect information

related to primary care for these programs, but OFM was not able to obtain this information for this

report.

For future primary care expenditures reports, Washington may want to consider developing a

standardized process to collect, across payers, a variety of non-claims-based investments. Outlined

below are several such areas and examples.

Provider incentives

Provider incentives such as those to encourage providers to adopt certain behaviors or pay providers

based on performance are often included in non-claims-based investments in primary care. Oregon

includes retrospective incentive payments “to primary care providers or practices based on their

performance at decreasing cost or improving value for a defined population” and prospective

incentive payments “to providers or practices aimed at developing capacity for improving care for a

defined population of patients.”

3

For example, Oregon collects information on bonus payments to

providers when they meet a target for vaccination rates. Rhode Island collects information on

incentive distributions under shared savings contracts.

Washington should consider how to collect information on provider incentives, including:

• Carrier-specific quality improvement programs aimed at specific in-network providers.

• State-sponsored quality improvement initiatives such as pay for performance metrics or

other bonus payments to providers.

• Federal quality improvement initiatives such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid

Services Merit-Based Incentive Payment System.

Patient-Centered Medical Home Models

According to the American College of Physicians, a Patient-Centered Medical Home, or PCMH, is a

care delivery model whereby treatment is coordinated through the patient’s primary care physician to

ensure they receive the necessary care when and where they need it, in a manner they can

understand. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality defines the core functions of the

medical home as follows:

4

• comprehensive care

• patient-centered

• coordinated care

3

Ibid.

4

https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh Accessed Oct 2019.

Primary Care Expenditures Report 14

• accessible services

• quality and safety

Oregon and Rhode Island collect information from carriers on investments in PCMH models (in

addition to provider incentives). Oregon has a Patient-Centered Primary Care Home program that

allows for the inclusion of the per-member per-month payment based upon a practice’s tier level.

Rhode Island hosts a Care Transformation Collaborative, called CTC-RI, which brings together key

care stakeholders to promote care for patients with chronic disease through the PCMH model.

Rhode Island’s only multi-payer PCMH initiative, it helps practices apply for national PCMH

recognition, hire on-site care management/coordination to improve the health of patients with the

highest needs, and enhance data capabilities to manage and improve population health.

5

Additionally, Oregon and Rhode Island collect information on investments from carriers on other

PCMH initiatives.

Washington should consider how to collect information on practice and provider PCMH payments

and how to include this information in future reports, e.g., carrier-specific investments or aggregated

payments at the state level.

Investments in technology

Oregon and Rhode Island collect information on investments in primary care related to health

information technology. These investments include payments to providers to adopt electronic

medical records or payments for providers’ license fees. Additionally, Rhode Island, which requires

health insurance companies to invest in the state health information exchange called CurrentCare,

includes this investment in insurers’ non-claims-based expenditures.

In deciding which technology to include in primary care investments, Washington stakeholders

should consider not only the four main features of primary care (first-contact, continuous,

comprehensive and coordinated), but also technology advances that improve health equity. Below

are ideas for the types of technology investments that stakeholders in Washington may want to

consider:

• Technology to promote interoperability of electronic health records between providers and

facilities.

• Telehealth services including secure online chat tools for members to speak with primary

care providers and for video visits with providers.

• Texting services for reminders of appointments, lab test results or provider communication.

• Mobile applications to access medical records, pay bills or order refills on medications.

• E-consults between providers through electronic medical record platforms.

• Transcription services or talk-to-text services to help input information directly into

electronic medical records.

• Investments in OneHealthPort to improve the state’s health information exchange.

• Grants from state programs or federal programs to promote the exchange of health

information.

5

https://www.ctc-ri.org/about-us/what-ctc-ri Accessed Oct 2019.

Primary Care Expenditures Report 15

Many of the investments in technology previously mentioned may not be exclusive to primary care,

and care should be taken if these types of investments are counted toward future primary care

investments.

Workforce expenditures

In addition to typical staffing of primary care offices for administrative roles or billing, many of the

non-claims-based initiatives already mentioned — investments in technology, provider incentives

and PCMH models — require supplemental primary care staff and activities. Oregon and Rhode

Island collect non-claims-based primary care expenditures for certain workforce investments such as

practice coaches, patient educators, patient navigators and nurse case managers. Embedding

supplemental staff, including registered nurses and practice coaches, in primary care supports the

“whole person” model, will be in greater demand as the prevalence of multiple chronic conditions

increases and can improve patient health outcomes (Bauer & Bodenheimer, 2017; Grumbach, K.,

Bainbridge, E., and Bodenheimer, T., 2012).

Examples of how supplemental staff can benefit a primary care setting are:

• Implementing electronic medical records or a health information exchange.

• Providing technical support for technology enhancements in care delivery.

• Supporting adoption of new models of care delivery and continuous quality improvement.

• Helping patients change or adapt unhealthy behaviors (e.g., weight loss or smoking

cessation).

• Improving care of chronic conditions, including medication adherence.

• Connecting patients with social services.

• Improving cultural competence among clinic staff.

• Integrating behavioral health services.

• Managing continuity of care.

In addition to investments in supplemental staff, investments in primary care providers is needed to

maintain enough providers to support Washington’s growing population. Baicker and Chandra

(2004) found that states where more physicians are general practitioners have greater use of high-

quality care and lower cost per beneficiary (among Medicare patients).

Although there are numerous ways to increase and maintain the primary care provider workforce in

Washington — preventing provider burnout, increasing the number of residency slots in primary

care, increasing the funding for primary care provider education — this report will focus only on

one area, loan repayment, because Rhode Island has useful experience from which Washington can

draw information.

The Washington Student Achievement Council and the Department of Health administer two

programs to help health professionals pay back student loan debt. The median amount of that debt

is about:

• $200,000 for medical school (for class of 2018) (American Association of Medical Colleges,

2018)

• $112,500 for physician assistants (for class of 2018) (National Commission on Certification

of Physician Assistants, 2019)

• $40,000 to $55,000 for graduate nursing education (class of 2016, most recent year available)

(American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2017)

Primary Care Expenditures Report 16

The Federal-State Loan Repayment Program, or FSLRP, awards $70,000 for loan reimbursement

with federal and state funds in return for two years of full-time work at an approved site. The Health

Professional Loan Repayment Program, or HPLRP, is a state-funded award that reimburses $75,000

of loans for three years of full-time employment (or five years for less than full-time employment).

This program requires the approved site to meet the definition of providing comprehensive primary

care services: comprehensive outpatient, ambulatory and primary health care services. This

definition includes critical access or rural hospitals but excludes all other hospitals. (Program-specific

criteria are available from the WSAC website.

6

) In the last cycle (funds obligated in fiscal year 2015–

16 and disbursed in fiscal years 2016–18 for FSLRP and fiscal years 2016–19 for HPLRP), 72

primary care providers (who also matched the definition of primary care used in this study) were

awarded more than $4.4 million in student loan debt relief.

Other investments

Additional types of investments that Oregon or Rhode Island collected and included in its non-

claims (or non-fee-for-service) primary care expenditure calculations included:

• Vaccine clinics (specifically for influenza vaccines)

• Integration of behavioral health services (outside of supplemental staff)

• Risk-based reconciliation

• Capitated or salaried expenditures not captured in claims

In considering the broad context of primary care, investments in evaluation and research on primary

care services, community-based programs to address social determinants of health and activities

undertaken by community health workers could all be counted as primary care expenditures

although they may not be part of the direct delivery of primary care services. Understanding and

defining the sphere in which primary care is taking place outside of the fee-for-service system is

essential for capturing non-claims-based investments in primary care (Baillieu et al., 2019). In

addition to what has already been mentioned about caveats to collecting non-claims-based

investments or expenditures for primary care, future reports will want to consider mechanisms to

evaluate these types of expenditures and how to allow for their inclusion over time.

Limitations of current report

This is the first comprehensive analysis of annual primary care expenditures in Washington using

claims data from the WA-APCD. Although future reports may continue to use claims data extracted

from the WA-APCD or other sources, there are inherent limitations to health care claims data from

any data source. The gaps in data identified during the study included the following:

Procedure codes

The stakeholder group conducted an extensive review of primary care procedure codes. This report

included all procedures from various reports on primary care (Bailit et al., 2017; Oregon Health

Authority and the Department of Consumer and Business Services, 2019; Reid et al., 2019) and

additional codes the stakeholder group identified as services performed in primary care settings by

primary care providers. Even with the exhaustive list of codes, there could still be procedures that

were not included in this report, but are billed for by primary care providers (e.g., hospice visits,

6

https://wsac.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2019.FSLRP.HPLRP.Guide.pdf Accessed Sept 2019.

Primary Care Expenditures Report 17

charges for vaccines). Caution should be used when comparing this report to other reports that do

not use the same codes.

No primary care location indicator

We were not able to identify if the setting for the primary care service was a primary care clinic or

other type of health care setting; this information is not captured on claims submitted to the WA-

APCD. It is unclear if this underestimated or overestimated the true level of primary care

expenditures for the state. OFM is working on solutions to gather the primary care location

information for future reports.

No primary care provider roster or consensus on definition

Without a roster or other continually updated source for primary care providers for Washington,

stakeholder groups will need to determine and define who is a primary care provider outside of

relying on just the taxonomy code. This is especially important for nurse practitioners and physician

assistants: It is unclear from the methods used to define primary care and the adjustment used for

nurse practitioners and physician assistants if we over- or under-estimated primary care providers for

the state. Additionally, not all reports have included obstetrics and behavioral health as primary care

providers. Without a national standard or consensus on definition of primary care providers, it will

continue to be difficult to compare estimates between reports.

Bundled payment services

As health care services move to bundled payments for services (e.g., obstetrics), it becomes difficult

to carve out which services are attributable or defined as primary care (e.g., prenatal visits). Future

reports should consider possible adjustments to methodology to identify and capture primary care

services within bundled payments.

Federally Qualified Health Centers and rural health centers

Claims submitted by Federally Qualified Health Centers or rural health centers may be submitted by

the facility or by the individual provider. Because this practice varies by location, an accurate

estimate of primary care services delivered at or by these facilities cannot be determined.

Integrated delivery systems

Some health insurance carriers are part of integrated delivery systems or use capitated payments.

These type of systems do not follow the traditional fee-for-service model when paying for health

care services. Although the methodology in this report used the fee-for-service equivalent in claims

data for capitated payments, there could still be an underestimate of primary care expenditures for

these services that could result in an underestimate of the true primary care investment by these

health insurance carriers.

Medicaid fee-for-service and Medicare fee-for-service claims

Neither Oregon nor Rhode Island, nor the current report for Washington include Medicaid fee-for-

service or Medicare fee-for-service primary care expenditures. These results could be inferred from

results calculated for Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care organizations, but these

results would not take into account differences in population characteristics, health status or

reimbursement rates between the fee-for-service groups and the managed care groups. Future

reports may want to consider including these health insurance claims to better understand how

investments in primary care differ among these populations.

Primary Care Expenditures Report 18

Non-claims-based expenditures

As discussed previously in this report, there is no standardized statewide system in place to collect

non-claims-based expenditures from health insurance carriers in Washington. Although not all

primary care reports have used this type of data, Oregon and Rhode Island used it in their reports.

Without non-claims-based expenditures, estimates of primary care spending will appear lower in

Washington compared with states that collect these data.

Future considerations

This report provides a baseline estimate of primary care spending in Washington. This estimate can

be used to monitor primary care spending and to compare the impacts of new investments and

initiatives. Future reports should continue to evaluate limitations to evolving methodology and

measurements. However, if future iterations of this report update or add codes or services, any

changes in spending results could be due to these changes in methodology and may not be the result

of any policy or behavior change. Oregon updated its inclusion of costs and primary care service

codes between its reports released in 2018 and 2019 (Oregon Health Authority and the Department

of Consumer and Business Services, 2019). There was no discussion on how this may have

influenced its primary care expenditure results between reports.

Because primary care utilization is heavily influenced by needs of the population, future reports may

include more detailed stratifications of population characteristics (e.g., sex, comorbidity, geography)

to better understand variations in primary care spending. These population characteristics could help

explain differences in primary care spending by market sector and by carriers outside of provider

networks and business agreements.

This report cannot differentiate how spending among carriers in different market sectors correlates

with quality of services, patient and provider satisfaction, or population health outcomes. If

additional population characteristics are included in future reports, additional indicators previously

mentioned should also be considered for collection

If non-claims-based expenditures are to be collected and included in future iterations of this report,

care should be given on whether to consider these types of investments as spending in addition to

what is identified from claims and fee-for-service expenditures.

Conclusion

This primary care spending report provides not only a baseline to compare new investments or

initiatives, but also caveats and considerations for how to continue to measure primary care

expenditures.

The results in this report highlight a low rate of investment in primary care in Washington. Based on

current research, the health care system would benefit from increased primary care investments. To

ensure the best results, decisions should be guided by additional research into best practices based

on current evidence, available data and broad stakeholder input. Monitoring the impact of policies

and system performance will be key to successfully strengthening Washington’s primary care system

(Center for Health Care Strategies and State Health Access Data Assistance Center, 2014).

Primary Care Expenditures Report 19

Future stakeholders should pose the following questions suggested by Koller et al (Koller, C.F.,

Khullar, 2017):

• What is the right level of primary care spending based on evidence?

• How large of an improvement in care outcomes could be expected with a unit increase in

primary care spending?

• How does the effect of additional spending on primary care vary with the patient population

being served?

State-level efforts to control costs and increase primary care spending are possible. Rhode Island’s

efforts to control costs have resulted in decreased overall spending among commercial insurers

through lower prices while increasing primary care spending without affecting quality or utilization

(Baum et al., 2019).

Primary Care Expenditures Report 20

References

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2017). The Numbers Behind the Degree: Financing

Graduate Nursing Education. Retrieved from https://www.aacnnursing.org/Policy-

Advocacy/View/ArticleId/20715/AACN-Releases-2017-Graduate-Nursing-Student-Debt-

Report

American Association of Medical Colleges. (2018). October 2018 Medical Student Education: Debt,

Costs, and Loan Repayment Fact Card. Retrieved October 17, 2019, from

https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/240/

Baicker, K., & Chandra, A. (2004). Medicare spending, the physician workforce, and beneficiaries’

quality of care. Health Affairs, 23(SUPPL.), 184–197. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.W4.184

Bailit, M. H., Friedberg, M. W., & Houy, M. L. (2017). Standardizing the Measurement of Commercial

Health Plan Primary Care Spending. Retrieved from www.milbank.org

Baillieu, R., Kidd, M., Phillips, R., Roland, M., Mueller, M., Morgan, D., … Bazemore, A. (2019).

The Primary Care Spend Model: A systems approach to measuring investment in primary care.

BMJ Global Health, 4(4). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001601

Basu, S., Berkowitz, S. A., Phillips, R. L., Bitton, A., Landon, B. E., & Phillips, R. S. (2019).

Association of Primary Care Physician Supply With Population Mortality in the United States,

2005-2015. JAMA Internal Medicine, 179(4), 506–514.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7624

Bauer, L., & Bodenheimer, T. (2017). Expanded roles of registered nurses in primary care delivery of

the future. Nursing Outlook, 65(5), 624–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2017.03.011

Baum, A., Song, Z., Landon, B. E., Phillips, R. S., Bitton, A., & Basu, S. (2019). Health care

spending slowed after Rhode Island applied affordability standards to commercial insurers.

Health Affairs, 38(2), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05164

Center for Health Care Strategies & State Health Access Data Assistance Center. (2014). Multi-Payer

Investments in Primary Care: Policy and Measurement Strategies. Trenton, NJ.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Tables of Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Adults:

2018 National Health Interview (Vol. 0). Retrieved from

http://www.cdc/gov/nchs/nhs/SHS/tables.htm

Donaldson, M.S., Yordy, K.D., Lohr, K.N., & Vanselow, N. A. (Ed.). (1996). Primary Care: America’s

Health in a New Era. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.4960190202

Friedberg, M. W., Hussey, P. S., & Schneider, E. C. (2010). Primary care: A critical review of the

evidence on quality and costs of health care. Health Affairs, 29(5), 766–772.

https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0025

Glass, D. P., Kanter, M. H., Jacobsen, S. J., & Minardi, P. M. (2017). The impact of improving

access to primary care. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 23(6), 1451–1458.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12821

Primary Care Expenditures Report 21

Grumbach, K., Bainbridge, E., and Bodenheimer, T. (2012). Facilitating Improvement in Primary

Care: The Promise of Practice Coaching. Commonwealth Fund, 15 (pub. 1605). Retrieved from

https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publicat

ions_issue_brief_2012_jun_1605_grumbach_facilitating_improvement_primary_care_practice_

coaching.pdf

Jabbarpour, Y., Greiner, A., Jetty, A., Coffman, M., Jose, C., Petterson, S. et al. (2019). Investing in

primary care: A state-level analysis. Retrieved from https://www.pcpcc.org/resource/evidence2019

Kaplan, L., & Gill, J. (2018). 2018 Washington State Advanced Registered Nurse Practitioner Survey Data

Report. Vancouver, WA.

King, C. (2019). Email Communication.

Koller, C.F., Khullar, D. (2017). Primary Care Spending Rate – A Lever for Encouraging Investment

in Primary Care. New England Journal of Medicine, 377(18), 1709–1711.

National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. (2019). 2018 Statistical Profile of Recently

Certified Physician Assistants: An Annual Report of the National Commission on Certification of Physician

Assistants. Retrieved from http://www.nccpa.net

OECD. (2017). Health at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators. Retrieved from

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2017-en

Oregon Health Authority and the Department of Consumer and Business Services. (2019). Primary

Care Spending in Oregon: A Report to the Oregon Legislature. Retrieved from

https://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/ANALYTICS/Documents/SB-231-Report-2019.pdf

Reid, R., Damberg, C., & Friedberg, M. W. (2019, July 1). Primary Care Spending in the Fee-for-

Service Medicare Population. JAMA Internal Medicine, Vol. 179, pp. 977–980.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8747

Starfield, B., Shi, L., Macinko, J. (2005). Contribution of primary care to health systems and health.

Milbank Quarterly, 83(3), 457–502.

Starfield, B. (1998). Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. New York, NY:

Oxford University Press.

Washington Medical Commission. (2019). Physician Assistant Demographic Census Aggregate Report.

Retrieved from https://wmc.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/PAReportOctober2019.pdf

Yen, W. (2018). 2016 Physician Supply. Retrieved from

https://www.ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/dataresearch/healthcare/workforce/physi

cian_supply_2016.pdf

Primary Care Expenditures Report 22

Appendix A: Budget proviso

ESHB 1109, Section 131(9)

(9) $110,000 of the general fund—state appropriation for fiscal year 2020 is provided solely for the

office of financial management to determine annual primary care medical expenditures in

Washington, by insurance carrier, in total and as a percentage of total medical expenditure. Where

feasible, this determination must also be broken down by relevant characteristics such as whether

expenditures were for in-patient or out-patient care, physical or mental health, by type of provider,

and by payment mechanism.

(a) The determination must be made in consultation with statewide primary care provider

organizations using the state's all payer claims database and other existing data.

(b) For purposes of this section:

(i) "Primary care" means family medicine, general internal medicine, and general

pediatrics.

(ii) "Primary care provider" means a physician, naturopath, nurse practitioner,

physician assistant, or other health professional licensed or certified in Washington

state whose clinical practice is in the area of primary care.

(iii) "Primary care medical expenditures" means payments to reimburse the cost of

physical and mental health care provided by a primary care provider, excluding

prescription drugs, vision care, and dental care, whether paid on a fee-for-service

basis or as a part of a capitated rate or other type of payment mechanism.

(iv) "Total medical expenditure" means payments to reimburse the cost of all health

care and prescription drugs, excluding vision care and dental care, whether paid on a

fee-for-service basis or as part of a capitated rate or other type of payment

mechanism.

(c) By December 1, 2019, the office of financial management shall report its findings to the

legislature, including an explanation of its methodology and any limits or gaps in existing

data which affected its determination.

Primary Care Expenditures Report 23

Appendix B: Primary Care Expenditures Stakeholder Group

Office of Financial Management staff:

Thea Mounts

Mandy Stahre

Advanced Registered Nurse Practitioners United of Washington State:

Devon S. Connor-Green

Louise Kaplan

Washington Academy of Family Physicians:

Tony Butruille

Jonathan Seib

Alexa Silver

Jonathan Sugarman

Washington Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics:

Francie Chalmers

Sarah Rafton

Amber Ulvenes

University of Washington Center for Health Workforce Studies:

Bianca Frogner

Davis Patterson

Susan Skillman

University of Washington Department of Global Health:

Matthew Thompson

Washington Health Care Authority:

Rachel Quinn

Emily Transue

Judy Zerzan

Primary Care Expenditures Report 24

Appendix C: List of providers

Narrow definition of primary care provider

Taxonomy Code

Description

207Q00000X

Family Medicine

207QA0000X

Family Medicine, Adolescent Medicine

207QA0505X

Family Medicine, Adult Medicine

207QG0300X

Family Medicine, Geriatric Medicine

261QF0400X

Federally Qualified Health Center

208D00000X

General Practice

207R00000X

Internal Medicine

207RG0300X

Internal Medicine, Geriatric Medicine

175F00000X

Naturopath

208000000X

Pediatrics

2080A0000X

Pediatrics, Adolescent Medicine

2083P0500X

Preventive Medicine, Preventive

Medicine/Occupational Environmental Medicine

261QP2300X

Primary care clinic

261QR1300X

Rural health clinic

Nurse practitioner and physician assistant definitions

Taxonomy Code

Description

363L00000X

Nurse Practitioner

363LA2100X

Nurse Practitioner, Acute Care

363LA2200X

Nurse Practitioner, Adult Health

363LC1500X

Nurse Practitioner, Community Health

363LC0200X

Nurse Practitioner, Critical Care Medicine

363LF0000X

Nurse Practitioner, Family

363LG0600X

Nurse Practitioner, Gerontology

363LN0000X

Nurse Practitioner, Neonatal

363LN0005X

Nurse Practitioner, Neonatal, Critical Care

363LX0001X

Nurse Practitioner, Obstetrics & Gynecology

363LX0106X

Nurse Practitioner, Occupational Health

363LP0200X

Nurse Practitioner, Pediatrics

363LP0222X

Nurse Practitioner, Pediatrics, Critical Care

363LP1700X

Nurse Practitioner, Perinatal

363LP2300X

Nurse Practitioner, Primary Care

363LP0808X

Nurse Practitioner, Psychiatric/Mental Health

363LS0200X

Nurse Practitioner, School

363LW0102X

Nurse Practitioner, Women’s Health

363A00000X

Physician Assistant

363AM0700X

Physician Assistant, Medical

363AS0400X

Physician Assistant, Surgical

Primary Care Expenditures Report 25

Broad definition of primary care provider

Taxonomy Code

Description

367A00000X

Advanced Practice Midwife

106E00000X Assistant Behavior Analyst

106S00000X Behavior Technician

103K00000X

Behavioral Analyst

103G00000X Clinical Neuropsychologist

364S00000X Clinical Nurse Specialist

163W00000X Registered Nurse

101Y00000X

Counselor

101YA0400X Counselor, Addiction (Substance Use Disorder)

101YM0800X Counselor, Mental Health

101YP1600X

Counselor, Pastoral

101YP2500X Counselor, Professional

101YS0200X Counselor, School

207QA0401X

Family Medicine, Addiction Medicine

207QB0002X Family Medicine, Bariatric Medicine

207QH0002X Family Medicine, Hospice and Palliative Medicine

207QS1201X Family Medicine, Sleep Medicine

207QS0010X

Family Medicine, Sports Medicine

175L00000X Homeopath

207RA0401X Internal Medicine, Addiction Medicine

106H00000X

Marriage & Family Therapist

176B00000X Midwife

207V00000X Obstetrics & Gynecology

207VG0400X

Obstetrics & Gynecology, Gynecology

2080P0006X

Pediatrics, Developmental – Behavioral Pediatrics

2080P0008X Pediatrics, Neurodevelopmental Disabilities

2084A0401X

Psychiatry & Neurology, Addiction Medicine

2084P0802X

Psychiatry & Neurology, Addiction Psychiatry

Broad definition of primary care provider

Taxonomy Code

Description

2084P0804X

Psychiatry & Neurology, Child & Adolescent

Psychiatry

2084F0202X Psychiatry & Neurology, Forensic Psychiatry

2084P0805X Psychiatry & Neurology, Geriatric Psychiatry

2084P0005X

Psychiatry & Neurology, Neurodevelopmental

Disabilities

2084P0800X

Psychiatry & Neurology, Psychiatry

2084P0015X Psychiatry & Neurology, Psychosomatic Medicine

102L00000X Psychoanalyst

103T00000X

Psychologist

103TA0400X Psychologist, Addiction (Substance Use Disorder)

103TA0700X Psychologist, Adult Development & Aging

103TC0700X

Psychologist, Clinical

103TC2200X Psychologist, Clinical Child & Adolescent

103TB0200X Psychologist, Cognitive & Behavioral

103TC1900X Psychologist, Counseling

103TE1000X

Psychologist, Educational

103TE1100X Psychologist, Exercise & Sports

103TF0000X Psychologist, Family

103TF0200X

Psychologist, Forensic

103TP2701X Psychologist, Group Psychotherapy

103TH0004X Psychologist, Health

103TH0100X

Psychologist, Health Service

103TM1700X

Psychologist, Men & Masculinity

103TM1800X

Psychologist, Mental Retardation & Developmental

Disabilities

103TP0016X Psychologist, Prescribing (Medical)

103TP0814X

Psychologist, Psychoanalysis

103TP2700X Psychologist, Psychotherapy

103TR0400X Psychologist, Rehabilitation

Primary Care Expenditures Report 26

Broad definition of primary care provider

Taxonomy Code

Description

103TS0200X

Psychologist, School

103TW0100X Psychologist, Women

104100000X Social Worker

1041C0700X

Social Worker, Clinical

1041S0200X Social Worker, School

Primary Care Expenditures Report 27

Appendix D: Procedure codes

Narrow definition of procedures

HCPCs or

CPT codes

Procedure Category Procedure Long Description

99497

Advance Care Planning Evaluation &

Management Services

ADVANCE CARE PLANNING FIRST 30 MINS

99498

Advance Care Planning Evaluation &

Management Services

ADVANCE CARE PLANNING EA ADDL 30 MINS

99450

Basic Life and/or Disability Exam

BASIC LIFE AND/OR DISABILITY EXAMINATION

99455 Basic Life and/or Disability Exam WORK RELATED/MED DBLT XM TREATING PHYS

99456 Basic Life and/or Disability Exam WORK RELATED/MED DBLT XM OTH/THN TREATING PHYS

99366 Case Management Services TEAM CONFERENCE FACE-TO-FACE NONPHYSICIAN

99367 Case Management Services TEAM CONFERENCE NON-FACE-TO-FACE PHYSICIAN

99368

Case Management Services

TEAM CONFERENCE NON-FACE-TO-FACE NONPHYSICIAN

99487

Chronic Care Management Services

CMPLX CHRON CARE MGMT W/O PT VST 1ST HR PER MO

99489

Chronic Care Management Services

CMPLX CHRON CARE MGMT EA ADDL 30 MIN PER MONTH

99490

Chronic Care Management Services

CHRON CARE MANAGEMENT SRVC 20 MIN PER MONTH

G0506

Chronic Care Management Services

COMP ASMT OF & CARE PLNG PT RQR CC MGMT SRVC

99241

Consultation Services

OFFICE CONSULTATION NEW/ESTAB PATIENT 15 MIN

99242 Consultation Services OFFICE CONSULTATION NEW/ESTAB PATIENT 30 MIN

99243 Consultation Services OFFICE CONSULTATION NEW/ESTAB PATIENT 40 MIN

99244 Consultation Services OFFICE CONSULTATION NEW/ESTAB PATIENT 60 MIN

G0438 Counseling, Screening, & Prevention Services ANNUAL WELLNESS VISIT; PERSONALIZ PPS INIT VISIT

G0439

Counseling, Screening, & Prevention Services

ANNUAL WELLNESS VST; PERSONALIZED PPS SUBSQT VST

G0442

Counseling, Screening, & Prevention Services

ANNUAL ALCOHOL MISUSE SCREENING 15 MINUTES

G0443

Counseling, Screening, & Prevention Services

BRIEF FACE-FACE BEHAV CNSL ALCOHL MISUSE 15 MIN

99324

Domiciliary, Rest Home or Custodial Care

DOMICIL/REST HOME NEW PT VISIT LOW SEVER 20 MIN

99325

Domiciliary, Rest Home or Custodial Care

DOMICIL/REST HOME NEW PT VISIT MOD SEVER 30 MIN

99326

Domiciliary, Rest Home or Custodial Care

DOMICIL/REST HOME NEW PT HI-MOD SEVER 45 MINUTES

99327 Domiciliary, Rest Home or Custodial Care DOMICIL/REST HOME NEW PT VISIT HI SEVER 60 MIN

Primary Care Expenditures Report 28

Narrow definition of procedures

HCPCs or

CPT codes

Procedure Category Procedure Long Description

99328

Domiciliary, Rest Home or Custodial Care

DOM/R-HOME E/M NEW PT SIGNIF NEW PROB 75 MINUTES

99334

Domiciliary, Rest Home or Custodial Care

DOM/R-HOME E/M EST PT SELF-LMTD/MINOR 15 MINUTES

99335

Domiciliary, Rest Home or Custodial Care

DOM/R-HOME E/M EST PT LW MOD SEVERITY 25 MINUTES

99336

Domiciliary, Rest Home or Custodial Care

DOM/R-HOME E/M EST PT MOD HI SEVERITY 40 MINUTES

99337 Domiciliary, Rest Home or Custodial Care DOM/R-HOME E/M EST PT SIGNIF NEW PROB 60 MINUTES

99078 Educational Service Group Setting PHYS/QHP EDUCATION SVCS RENDERED PTS GRP SETTING

G0466 FQHC Visits FEDERALLY QUALIFIED HEALTH CENTER VISIT NEW PT

G0467 FQHC Visits FEDERALLY QUALIFIED HEALTH CENTER VISIT ESTAB PT

G0468 FQHC Visits FEDERALLY QUALIFIED HEALTH CENTER VISIT IPPE/AWV

G0469

FQHC Visits

FED QUAL HEALTH CNTR VISIT MENTAL HEALTH NEW PT

G0470

FQHC Visits

FED QUAL HEALTH CNTR VST MENTAL HEALTH ESTAB PT

T1015

FQHC Visits - T1015

CLINIC VISIT/ENCOUNTER ALL-INCLUSIVE

96160

Health Risk Assessment & Screenings

PT-FOCUSED HLTH RISK ASSMT SCORE DOC STND INSTRM

96161

Health Risk Assessment & Screenings

CAREGIVER HLTH RISK ASSMT SCORE DOC STND INSTRM

99339

Health Risk Assessment & Screenings